Adansonia Digitata) to Improve Food Security

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Adansonia Grandidieri

The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species™ ISSN 2307-8235 (online) IUCN 2008: T30388A64007143 Adansonia grandidieri Assessment by: Ravaomanalina, H. & Razafimanahaka, J. View on www.iucnredlist.org Citation: Ravaomanalina, H. & Razafimanahaka, J. 2016. Adansonia grandidieri. The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species 2016: e.T30388A64007143. http://dx.doi.org/10.2305/IUCN.UK.2016- 2.RLTS.T30388A64007143.en Copyright: © 2016 International Union for Conservation of Nature and Natural Resources Reproduction of this publication for educational or other non-commercial purposes is authorized without prior written permission from the copyright holder provided the source is fully acknowledged. Reproduction of this publication for resale, reposting or other commercial purposes is prohibited without prior written permission from the copyright holder. For further details see Terms of Use. The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species™ is produced and managed by the IUCN Global Species Programme, the IUCN Species Survival Commission (SSC) and The IUCN Red List Partnership. The IUCN Red List Partners are: BirdLife International; Botanic Gardens Conservation International; Conservation International; Microsoft; NatureServe; Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew; Sapienza University of Rome; Texas A&M University; Wildscreen; and Zoological Society of London. If you see any errors or have any questions or suggestions on what is shown in this document, please provide us with feedback so that we can correct or extend the information provided. THE IUCN RED LIST OF THREATENED -

Dry Forest Trees of Madagascar

The Red List of Dry Forest Trees of Madagascar Emily Beech, Malin Rivers, Sylvie Andriambololonera, Faranirina Lantoarisoa, Helene Ralimanana, Solofo Rakotoarisoa, Aro Vonjy Ramarosandratana, Megan Barstow, Katharine Davies, Ryan Hills, Kate Marfleet & Vololoniaina Jeannoda Published by Botanic Gardens Conservation International Descanso House, 199 Kew Road, Richmond, Surrey, TW9 3BW, UK. © 2020 Botanic Gardens Conservation International ISBN-10: 978-1-905164-75-2 ISBN-13: 978-1-905164-75-2 Reproduction of any part of the publication for educational, conservation and other non-profit purposes is authorized without prior permission from the copyright holder, provided that the source is fully acknowledged. Reproduction for resale or other commercial purposes is prohibited without prior written permission from the copyright holder. Recommended citation: Beech, E., Rivers, M., Andriambololonera, S., Lantoarisoa, F., Ralimanana, H., Rakotoarisoa, S., Ramarosandratana, A.V., Barstow, M., Davies, K., Hills, BOTANIC GARDENS CONSERVATION INTERNATIONAL (BGCI) R., Marfleet, K. and Jeannoda, V. (2020). Red List of is the world’s largest plant conservation network, comprising more than Dry Forest Trees of Madagascar. BGCI. Richmond, UK. 500 botanic gardens in over 100 countries, and provides the secretariat to AUTHORS the IUCN/SSC Global Tree Specialist Group. BGCI was established in 1987 Sylvie Andriambololonera and and is a registered charity with offices in the UK, US, China and Kenya. Faranirina Lantoarisoa: Missouri Botanical Garden Madagascar Program Helene Ralimanana and Solofo Rakotoarisoa: Kew Madagascar Conservation Centre Aro Vonjy Ramarosandratana: University of Antananarivo (Plant Biology and Ecology Department) THE IUCN/SSC GLOBAL TREE SPECIALIST GROUP (GTSG) forms part of the Species Survival Commission’s network of over 7,000 Emily Beech, Megan Barstow, Katharine Davies, Ryan Hills, Kate Marfleet and Malin Rivers: BGCI volunteers working to stop the loss of plants, animals and their habitats. -

Species of Baobab in Madagascar Rajeriarison, 2010 with 6 Endemics : Adansonia Grandidieri, A

FLORA OF MADAGASCAR Pr HERY LISY TIANA RANARIJAONA Doctoral School Naturals Ecosystems University of Mahajanga [email protected] Ranarijaona, 2014 O7/10/2015 CCI IVATO ANTANANARIVO Originality Madagascar = « megabiodiversity », with 5 % of the world biodiversity (CDB, 2014). originality et diversity with high endemism. *one of the 25 hot spots 7/9 species of Baobab in Madagascar Rajeriarison, 2010 with 6 endemics : Adansonia grandidieri, A. rubrostipa, A. za, A. madagascariensis, A. perrieri et A. suarezensis. Ranarijaona, 2013 Endemism Endemism : *species : 85 % - 90 % (CDB, 2014) *families : 02,46 % * genera : 20 à 25 % (SNB, 2012) *tree and shrubs (Schatz, 2001) : - familles : 48,54 % - genres : 32,85 % CDB, 2014 - espèces : 95,54 % RANARIJAONA, 2014 Families Genera Species ASTEROPEIACEAE 1 8 SPHAEROSEPALACEAE PHYSENACEAE 1 1 SARCOLAENACEAE 10 68 BARBEUIACEAE 1 1 PHYSENACEAE 1 2 RAJERIARISON, 2010 Archaism •DIDIEREACEAE in the south many affinities with the CACTACEAE confined in South America : Faucherea laciniata - Callophyllum parviflorum • Real living fossils species : * Phyllarthron madagascariensis : with segmented leaves * species of Dombeya : assymetric petales * genera endemic Polycardia, ex : P. centralis : inflorescences in nervation of the leaf * Takhtajania perrieri : Witness living on the existence of primitive angiosperms of the Cretaceous in Madagascar RAJERIARISON, 2010 Tahina spectabilis (Arecaceae) Only in the west of Madagascar In extinction (UICN, 2008) Metz, 2008) Inflorescence : ~4 m Estimation of the floristic richness (IUCN/UNEP/WWF, 1987; Koechlin et al., 1974; Callmander, 2010) Authors years Families Genera Species Perrier de la 1936 191 1289 7370 Bathie Humbert 1959 207 1280 10000 Leroy 1978 160 - 8200 White 1983 191 1200 8500 Guillaumet 1984 180 1600 12000 Phillipson et al. -

Dryland Tree Data for the Southwest Region of Madagascar: Alpha-Level

Article in press — Early view MADAGASCAR CONSERVATION & DEVELOPMENT VOLUME 1 3 | ISSUE 01 — 201 8 PAGE 1 ARTICLE http://dx.doi.org/1 0.431 4/mcd.v1 3i1 .7 Dryland tree data for the Southwest region of Madagascar: alpha-level data can support policy decisions for conserving and restoring ecosystems of arid and semiarid regions James C. AronsonI,II, Peter B. PhillipsonI,III, Edouard Le Correspondence: Floc'hII, Tantely RaminosoaIV James C. Aronson Missouri Botanical Garden, P.O. Box 299, St. Louis, Missouri 631 66-0299, USA Email: ja4201 [email protected] ABSTRACT RÉSUMÉ We present an eco-geographical dataset of the 355 tree species Nous présentons un ensemble de données éco-géographiques (1 56 genera, 55 families) found in the driest coastal portion of the sur les 355 espèces d’arbres (1 56 genres, 55 familles) présentes spiny forest-thickets of southwestern Madagascar. This coastal dans les fourrés et forêts épineux de la frange côtière aride et strip harbors one of the richest and most endangered dryland tree semiaride du Sud-ouest de Madagascar. Cette région possède un floras in the world, both in terms of overall species diversity and des assemblages d’arbres de climat sec les plus riches (en termes of endemism. After describing the biophysical and socio-eco- de diversité spécifique et d’endémisme), et les plus menacés au nomic setting of this semiarid coastal region, we discuss this re- monde. Après une description du cadre biophysique et de la situ- gion’s diverse and rich tree flora in the context of the recent ation socio-économique de cette région, nous présentons cette expansion of the protected area network in Madagascar and the flore régionale dans le contexte de la récente expansion du growing engagement and commitment to ecological restoration. -

Download Itinerary

ACROSS AFRICA TOURS & TRAVEL 2035 Sunset lake Road Newark Delaware 19702 | (+1)800-205-5754 | Fax 1 (424) 333-0903 | [email protected] Madagascar Wildlife Tour 14D/13N ( Comfort) Madagascar is known for his unique wildlife. Most of people are thinking that 02 days is too short to see wildlife. It’s not true. This tour is designed to see several animal species around Antananarivo. Animals are not in a cage except in Perieyras reserve where the reptiles are in good condition. You can hear the loud yelling of the biggest lemurs of Madagascar called Indri-Indri or Babakoto and the ring tailed lemurs at lemurs park for sure. This is a suitable tour for weekend or 02 free days in Madagascar Itinerary Day 1 Arrive in Madagascar Upon Arrival at Ivato International Airport. You will be welcomed by our Tours Staff. Once you have cleared customs formalities, our Guide will smooth through the rest of the arrivals process – currency exchange, setting up your phone with a new SIM card, and anything else you need. We will provide you 2 (two) SIM cards with Data + National Call + 5mn International call during your stay in Madagascar. Overnight and dinner at Pietra hotel Day 2 TANA - PALMARIUM After breakfast, you are going to join the Palmarium Reserve. Your trip will take around seven hours with some stops for photos or breaks if it is necessary. You need to take a boat to get there (From Manambato to Palmarium). You will arrive there at the end of the day, so you will check-in at the hotel and then begin the guided night walk — dinner and overnight at Akan’ny nof hotel. -

This Article Was Published in an Elsevier Journal. the Attached Copy

This article was published in an Elsevier journal. The attached copy is furnished to the author for non-commercial research and education use, including for instruction at the author’s institution, sharing with colleagues and providing to institution administration. Other uses, including reproduction and distribution, or selling or licensing copies, or posting to personal, institutional or third party websites are prohibited. In most cases authors are permitted to post their version of the article (e.g. in Word or Tex form) to their personal website or institutional repository. Authors requiring further information regarding Elsevier’s archiving and manuscript policies are encouraged to visit: http://www.elsevier.com/copyright Author's personal copy Available online at www.sciencedirect.com The evolution of floral gigantism Charles C Davis1, Peter K Endress2 and David A Baum3 Flowers exhibit tremendous variation in size (>1000-fold), visitation rates between smaller and larger flowers can ranging from less than a millimeter to nearly a meter in result in selection for increased floral size (e.g. [1,2–6]). diameter. Numerous studies have established the importance of increased floral size in species that exhibit relatively normal- Despite broad interest in size increase and its importance sized flowers, but few studies have examined the evolution of in organismal evolution [7], we know relatively little floral size increase in species with extremely large flowers or about whether flower size evolution at the extremes of flower-like inflorescences (collectively termed blossoms). Our the range is governed by the same rules that act on review of these record-breakers indicates that blossom average-sized flowers. -

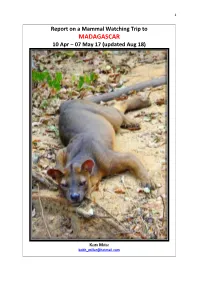

MADAGASCAR 10 Apr – 07 May 17 (Updated Aug 18)

1 Report on a Mammal Watching Trip to MADAGASCAR 10 Apr – 07 May 17 (updated Aug 18) Keith Millar [email protected] 2 Contents Itinerary and References (p3-p5) Conservation Issues (p6) Site by Site Guide: Berenty Private Reserve (p7-p10) Ranomafana National Park (p11-p15) Ankazomivady Forest (p15) Masoala National Park (p16-p18) Nosy Mangabe Special Reserve (pg 18) Kirindy Forest (pg19-p22) Ifaty-Mangily (pg23-p24) Andasibe/ Mantadia National Park (p25-p26) Palmarium Private Reserve (Ankanin’ny Nofy) (p27-p28) Montagne d’Ambre NP (p29-p30) Ankarana NP (P31-P32) Loboke Integrated Reserve (pg33-34) Checklists (pg35-p40) Grandidier’s Baobabs (Adansonia grandidieri) 3 In April 2017 I travelled with a friend, Stephen Swan, to Madagascar and spent 29 days focused on trying to locate as many mammal species as possible, together with the endemic birds and reptiles. At over 1,000 miles long and 350 miles wide, the world’s fourth largest island can be a challenge to get around, and transport by road is not always the practical option. So we also took several internal flights with Madagascar Airlines. In our experience, a reliable carrier, but when ‘technical difficulties’ did maroon us for some 24 hours, a pre-planned ‘extra’ day in the programme at least meant that we were able to stay ‘on target’ in terms of the sites and animals we wished to see. We flew Kenya Airlines to Antananarivo (Tana) via Nairobi (flights booked through Trailfinders https://www.trailfinders.com/ ) I chose Cactus Tours https://www.cactus-madagascar.com/ as our ground agent. -

Nectarivory by Endemic Malagasy Fruit Bats During the Dry Season1

BIOTROPICA 38(1): 85–90 2006 10.1111/j.1744-7429.2006.00112.x Nectarivory by Endemic Malagasy Fruit Bats During the Dry Season1 Daudet Andriafidison2,3, Radosoa A. Andrianaivoarivelo2,3, Olga R. Ramilijaona2,Marlene` R. Razanahoera2, James MacKinnon4,5, Richard K. B. Jenkins3,4,6, and Paul A. Racey4 2Department of Animal Biology, Faculty of Sciences, University of Antananarivo, Antananarivo (101), Madagascar 3Madagasikara Voakajy, B.P. 5181, Antananarivo (101), Madagascar 4School of Biological Sciences, University of Aberdeen, Aberdeen AB24 2TZ, UK 5Wildlife Conservation Society, B.P. 8500, Antananarivo (101), Madagascar ABSTRACT Madagascar has a distinctive fruit bat community consisting of Pteropus rufus, Eidolon dupreanum,andRousettus madagascariensis. In this study, we observed fruit bat visits to flowering baobabs (Adansonia suarezensis and Adansonia grandidieri) and kapok trees (Ceiba pentandra) during the austral winter. Eidolon dupreanum was recorded feeding on the nectar of baobabs and kapok, P. r u f u s was observed feeding on kapok only and no R. madagascariensis were seen. Three mammals species, two small lemurs (Phaner furcifer and Mirza coquereli)andE. dupreanum, made nondestructive visits to flowering A. grandidieri and are therefore all potential pollinators of this endangered baobab. This is the first evidence to show that A. grandidieri is bat-pollinated and further demonstrates the close link between fruit bats and some of Madagascar’s endemic plants. Eidolon dupreanum was the only mammal species recorded visiting A. suarezensis and visits peaked at the reported times of maximum nectar concentration. Pteropus rufus visited kapok mostly before midnight when most nectar was available, but E. dupreanum visited later in the night. -

Stem-Succulent Trees from the Old and New World Tropics

Copyright Notice This electronic reprint is provided by the author(s) to be consulted by fellow scientists. It is not to be used for any purpose other than private study, scholarship, or research. Further reproduction or distribution of this reprint is restricted by copyright laws. If in doubt about fair use of reprints for research purposes, the user should review the copyright notice contained in the original book from which this electronic reprint was made. Tree Physiology Guillermo Goldstein Louis S. Santiago Editors Tropical Tree Physiology Adaptations and Responses in a Changing Environment Guillermo Goldstein • Louis S. Santiago Editors Tropical Tree Physiology Adaptations and Responses in a Changing Environment 123 [email protected] Editors Guillermo Goldstein Louis S. Santiago Laboratorio de Ecología Funcional, Department of Botany & Plant Sciences Departamento de Ecología Genética y University of California Evolución, Instituto IEGEBA Riverside, CA (CONICET-UBA), Facultad de Ciencias USA Exactas y naturales Universidad de Buenos Aires and Buenos Aires Argentina Smithsonian Tropical Research Institute Balboa, Ancon, Panama and Republic of Panama Department of Biology University of Miami Coral Gables, FL USA ISSN 1568-2544 Tree Physiology ISBN 978-3-319-27420-1 ISBN 978-3-319-27422-5 (eBook) DOI 10.1007/978-3-319-27422-5 Library of Congress Control Number: 2015957228 © Springer International Publishing Switzerland 2016 This work is subject to copyright. All rights are reserved by the Publisher, whether the whole or part of the material is concerned, specifically the rights of translation, reprinting, reuse of illustrations, recitation, broadcasting, reproduction on microfilms or in any other physical way, and transmission or information storage and retrieval, electronic adaptation, computer software, or by similar or dissimilar methodology now known or hereafter developed. -

Grandidier's Baobab Adansonia Grandidieri, Madagascar

Grandidier’s Baobab Adansonia grandidieri, Madagascar (picture links: Adult Tree; Bernard Gagnon, Morondava; Flower; Seed) Seed type and characteristics: In leaf: October to May Flowers: May to August – said to smell of watermelon. Fruits: November Seed germination conditions: Easily grown from seed, apparently, though seeds need soaking in hot water for 2-6 hours, and then sowing about 1cm deep in a well-drained medium like river sand or perlite/vermiculite mix. Should not be overwatered. And pot should be kept in warm situation 68-75°F. Germination usually occurs in 2-4 weeks, though it can be more. Millenium Seed Bank advised approx. 11% rate germination of seeds (Jan 2016). Seeds scarified 95% conc. sulphuric acid treatment to break tough testa (February 2016). Sapling growing requirements: There is a series of U-tube videos on growing Adansonia digitata: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=t02_hJ1JpDA (part 1) https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=XMpJKL4lTwk (part 2) https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=AMK9EsneCYE (part 3) https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=WvMs_KGuOaA (part 4) https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=yGTj_n7YnyU (part 5) https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ZWrtNHGFgaQ (part 6) https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=B6drKFkMn4M (part 7) Conservation status: Endangered on the Red List1, and more background on GTC2 and Arkive3, and FAO’s Ecocrop4. CCI partners, with lead partner: Grandidier’s Baobab is one of the Global Tree Campaign species, so a focus of FFI5 and BGCI6, and FFI have a close collaboration with local partner, Madagasikara Voakajy (http://www.madagasikara-voakajy.org). BirdLife also have a well-established Partner in Madagascar, Asity Madagascar7, so there are a number of approaches to grandidieri on the ground. -

Samara English Edition 27 (PDF)

ISSUE 27 JULy – December 2014 ISSN 1475-8245 Thes Internationala Newsletterma of the Partners of the Millennium Seedr Banka Partnership www.kew.org/msbp/samara Ensuring the survival of rare and endangered plants By Sara Oldfield (Botanic Gardens Conservation International) One of the most charismatic globally threatened plant species is the Madagascan baobab Adansonia grandidieri, a giant, long-lived tree that is highly valued by local people for its edible fruits and seeds, medicinal products and its bark which is used in rope making. This extraordinary endangered tree, one of six baobab species found only in Madagascar, is an important part of local culture but without action could become extinct in the wild. This is just one of thousands of plant species that are close to extinction and may be pushed to the edge by climate change. The need for action is well known but much more needs to be done. Governments around the world have signed up to the Global Strategy for Plant Conservation (GSPC) pledging to take action to prevent the loss of plant diversity. The GSPC has 16 ambitious targets to be met by 2020. A new report on progress towards these targets, prepared by Botanic Gardens Conservation International (BGCI) notes that significant achievements have been made in plant conservation around the world but that few of the targets are likely to be met (Sharrock et al., 2014). Unfortunately we do not yet have the firm evidence base to use in calling for increased plant conservation action. Botanists need to act quickly to assess how many plant species are under threat around the world. -

A Potential Threat for the Grandidier's Baobab Adansonia Grandidieri In

MADAGASCAR CONSERVATION & DEVELOPMENT VOLUME 1 4 | ISSUE 01 — DECEMBER 201 9 PAGE 6 ARTICLE http://dx.doi.org/1 0.431 4/mcd.v1 4i1 .3 Bark harvesting: a potential threat for the Grandidier’s baobab Adansonia grandidieri in western Madagascar Daudet AndriafidisonI, Cynthia Onjanantenaina Correspondence: RavelosonII, Willy Sylvio MananjaraI, Julie Hanta Daudet Andriafidison RazafimanahakaI Madagasikara Voakajy, Lot II F 1 4 P Bis A Andraisoron, BP 51 81 , Antananarivo 1 01 , Madagascar Email: [email protected] ABSTRACT ont été réalisées sur 1 03 transects de 1 km de long entre avril The Grandidier’s baobab conveys the image of Madagascar world- 201 3 et janvier 201 4. Pour évaluer l’importance des écorces de wide. Locally, these trees have multiple uses with all parts of the baobab pour les riverains, des observations ont été conduites au plant being exploited by the population. We investigated the pat- niveau de quatre marchés de la région dans les villes de terns of bark harvesting on the Grandidier’s baobab in three dis- Bemanonga, Mahabo, Morondava et Analaiva au cours de la tricts in the Menabe Region: Mahabo, Manja and Morondava. même période. Au total, 21 594 lanières d’écorce et 34 51 7 m de Following 1 03 transects of 1 km each, we found that 54.0% of the corde de baobab ont été recensés dans les quatre marchés. La baobab trees had been subject to bark extraction. The mean total plus importante quantité d’écorce de baobabs commercialisée a area exploited per tree was 3,1 ± 0.2m2. Between April 201 3 and été enregistrée à Bemanonga.