“A Nation Blessed” George Bush

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

George Bush and the End of the Cold War. Christopher Alan Maynard Louisiana State University and Agricultural & Mechanical College

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses Graduate School 2001 From the Shadow of Reagan: George Bush and the End of the Cold War. Christopher Alan Maynard Louisiana State University and Agricultural & Mechanical College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses Recommended Citation Maynard, Christopher Alan, "From the Shadow of Reagan: George Bush and the End of the Cold War." (2001). LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses. 297. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses/297 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses by an authorized administrator of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has been reproduced from the microfilm master. UMI fiims the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from any type of computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction.. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are reproduced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand comer and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. -

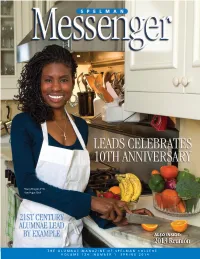

SPRING 2014 SPELMAN Messenger

Stacey Dougan, C’98, Raw Vegan Chef ALSO INSIDE: 2013 Reunion THE ALUMNAE MAGAZINE OF SPELMAN COLLEGE VOLUME 124 NUMBER 1 SPRING 2014 SPELMAN Messenger EDITOR All submissions should be sent to: Jo Moore Stewart Spelman Messenger Office of Alumnae Affairs ASSOCIATE EDITOR 350 Spelman Lane, S.W., Box 304 Joyce Davis Atlanta, GA 30314 COPY EDITOR OR Janet M. Barstow [email protected] Submission Deadlines: GRAPHIC DESIGNER Garon Hart Spring Semester: January 1 – May 31 Fall Semester: June 1 – December 31 ALUMNAE DATA MANAGER ALUMNAE NOTES Alyson Dorsey, C’2002 Alumnae Notes is dedicated to the following: EDITORIAL ADVISORY COMMITTEE • Education Eloise A. Alexis, C’86 • Personal (birth of a child or marriage) Tomika DePriest, C’89 • Professional Kassandra Kimbriel Jolley Please include the date of the event in your Sharon E. Owens, C’76 submission. TAKE NOTE! WRITERS S.A. Reid Take Note! is dedicated to the following Lorraine Robertson alumnae achievements: TaRessa Stovall • Published Angela Brown Terrell • Appearing in films, television or on stage • Special awards, recognition and appointments PHOTOGRAPHERS Please include the date of the event in your J.D. Scott submission. Spelman Archives Julie Yarbrough, C’91 BOOK NOTES Book Notes is dedicated to alumnae authors. Please submit review copies. The Spelman Messenger is published twice a year IN MEMORIAM by Spelman College, 350 Spelman Lane, S.W., We honor our Spelman sisters. If you receive Atlanta, Georgia 30314-4399, free of charge notice of the death of a Spelman sister, please for alumnae, donors, trustees and friends of contact the Office of Alumnae Affairs at the College. -

George HW Bush and CHIREP at the UN 1970-1971

University of New Orleans ScholarWorks@UNO University of New Orleans Theses and Dissertations Dissertations and Theses Spring 5-22-2020 The First Cut is the Deepest: George H.W. Bush and CHIREP at the U.N. 1970-1971 James W. Weber Jr. University of New Orleans, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.uno.edu/td Part of the American Popular Culture Commons, Asian History Commons, Cultural History Commons, Diplomatic History Commons, and the United States History Commons Recommended Citation Weber, James W. Jr., "The First Cut is the Deepest: George H.W. Bush and CHIREP at the U.N. 1970-1971" (2020). University of New Orleans Theses and Dissertations. 2756. https://scholarworks.uno.edu/td/2756 This Thesis is protected by copyright and/or related rights. It has been brought to you by ScholarWorks@UNO with permission from the rights-holder(s). You are free to use this Thesis in any way that is permitted by the copyright and related rights legislation that applies to your use. For other uses you need to obtain permission from the rights- holder(s) directly, unless additional rights are indicated by a Creative Commons license in the record and/or on the work itself. This Thesis has been accepted for inclusion in University of New Orleans Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@UNO. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The First Cut is the Deepest : George H.W. Bush and CHIREP at the U.N. 1970–1971 A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the University of New Orleans in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in History by James W. -

The Regime Change Consensus: Iraq in American Politics, 1990-2003

THE REGIME CHANGE CONSENSUS: IRAQ IN AMERICAN POLITICS, 1990-2003 Joseph Stieb A dissertation submitted to the faculty at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of History in the College of Arts and Sciences. Chapel Hill 2019 Approved by: Wayne Lee Michael Morgan Benjamin Waterhouse Daniel Bolger Hal Brands ©2019 Joseph David Stieb ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ii ABSTRACT Joseph David Stieb: The Regime Change Consensus: Iraq in American Politics, 1990-2003 (Under the direction of Wayne Lee) This study examines the containment policy that the United States and its allies imposed on Iraq after the 1991 Gulf War and argues for a new understanding of why the United States invaded Iraq in 2003. At the core of this story is a political puzzle: Why did a largely successful policy that mostly stripped Iraq of its unconventional weapons lose support in American politics to the point that the policy itself became less effective? I argue that, within intellectual and policymaking circles, a claim steadily emerged that the only solution to the Iraqi threat was regime change and democratization. While this “regime change consensus” was not part of the original containment policy, a cohort of intellectuals and policymakers assembled political support for the idea that Saddam’s personality and the totalitarian nature of the Baathist regime made Iraq uniquely immune to “management” strategies like containment. The entrenchment of this consensus before 9/11 helps explain why so many politicians, policymakers, and intellectuals rejected containment after 9/11 and embraced regime change and invasion. -

September 11 & 12 . 2008

n e w y o r k c i t y s e p t e m b e r 11 & 12 . 2008 ServiceNation is a campaign for a new America; an America where citizens come together and take responsibility for the nation’s future. ServiceNation unites leaders from every sector of American society with hundreds of thousands of citizens in a national effort to call on the next President and Congress, leaders from all sectors, and our fellow Americans to create a new era of service and civic engagement in America, an era in which all Americans work together to try and solve our greatest and most persistent societal challenges. The ServiceNation Summit brings together 600 leaders of all ages and from every sector of American life—from universities and foundations, to businesses and government—to celebrate the power and potential of service, and to lay out a bold agenda for addressing society’s challenges through expanded opportunities for community and national service. 11:00-2:00 pm 9/11 DAY OF SERVICE Organized by myGoodDeed l o c a t i o n PS 124, 40 Division Street SEPTEMBER 11.2008 4:00-6:00 pm REGIstRATION l o c a t i o n Columbia University 9/11 DAY OF SERVICE 6:00-7:00 pm OUR ROLE, OUR VOICE, OUR SERVICE PRESIDENTIAL FORUM& 101 Young Leaders Building a Nation of Service l o c a t i o n Columbia University Usher Raymond, IV • RECORDING ARTIST, suMMIT YOUTH CHAIR 7:00-8:00 pm PRESIDEntIAL FORUM ON SERVICE Opening Program l o c a t i o n Columbia University Bill Novelli • CEO, AARP Laysha Ward • PRESIDENT, COMMUNITY RELATIONS AND TARGET FOUNDATION Lee Bollinger • PRESIDENT, COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY Governor David A. -

Jean-Becker-KICD-Press-Release.Pdf

Kinder Institute on Constitutional Democracy announces distinguished MU alumna Jean Becker to serve on advisory board. Contact: Allison Smythe, 573.882.2124, smythea@missouri For more information on the Kinder Institute see democracy.missouri.edu COLUMBIA, Mo. – Today, the Kinder Institute on Constitutional Democracy at the University of Missouri announced that alumna Jean Becker, former chief of staff for George H. W. Bush, will serve on the institute’s advisory board, beginning July 1. “Jean Becker has had a remarkable career in journalism, government and public service,” said Justin Dyer, professor of political science and director of the Kinder Institute. “We look forward to working with her to advance the Kinder Institute’s mission of promoting teaching and scholarship on America’s founding principles and history.” Becker served as chief of staff for George H.W. Bush from March 1, 1994, until his death on Nov. 30, 2018. She supervised his office operations in both Houston, Texas, and Kennebunkport, Maine, overseeing such events as the opening of the George Bush Presidential Library Center in 1997, the commissioning of the USS George H.W. Bush aircraft carrier in January 2009, and coordinating special projects such as the Bush-Clinton Katrina Fund. She took a leave of absence in 1999 to edit and research All the Best, George Bush; My Life in Letters and Other Writings. Previously, Becker served as deputy press secretary to First Lady Barbara Bush from 1989 to 1992. After the 1992 election, she moved to Houston to help Mrs. Bush with the editing and research of her autobiography, Barbara Bush, A Memoir. -

Episode 62: “A Truly Historic Friendship” Featuring Secretary Baker

All the Best Podcast Episode 62: “A Truly Historic Friendship” Featuring Secretary of State and White House Chief of Staff under President George H. W. Bush, James Baker, III Secretary Baker: On August 21st, 1974, after President Ford announced his pick of Nelson Rockefeller for vice president, following that announcement, George wrote me this letter. Dear Bake. Yesterday was an enormous personal disappointment. For valid reasons, we made the finals. Valid reasons I mean a lot of hills, RNC, and letter support. And so the defeat was, therefore, more intense. But that was yesterday. Today and tomorrow will be different, for I see now clearly what it means to have really close friends more clearly than ever before in my life. I take personal pleasure from the great official support, but I take even more from the way our friends rallied around, and none did more than you to help me with a problem that burned my soul and my conscience. But the sun is about to come out, and life looks pretty darn good. Thanks. George. George: In the first place, I believe that character is a part of being president. Barbara: And life really must have joy. Sam: This is "All the Best." The official podcast of the George and Barbara Bush Foundation. I'm your host, Sam LeBlond, one of their many grandchildren. Here, we celebrate the legacy of these two incredible Americans through friends, family, and the foundation. This is, "All the Best." We're Mountaineers, volunteers We're the tide that rolls, we're Seminoles Yeah, we're one big country nation, that's right George: I remember something my dad taught me. -

Superpowers Walking a Tightrope: the Choices of April and May 1990 45

Superpowers Walking a Tightrope: The Choices of April and May 1990 45 Chapter 3 Superpowers Walking a Tightrope: The Choices of April and May 1990 Philip Zelikow and Condoleezza Rice This essay zeroes in on just a couple of months during some tumul- tuous years. It is a phase, in the spring of 1990, that happened after the initial diplomatic engagements following the opening of the Berlin Wall and before some of the final deals started emerging during the summer and autumn of 1990. We chose to focus on these two months, in our contribution to this volume, precisely because this phase—and these choices—have re- ceived relatively little notice. It was, however, an extraordinarily deli- cate and difficult phase in which progress could well have collapsed— but did not. Just to help readers set the scene: The East German elections of March 18, 1990 decided, in effect, that a unification of Germany would take place soon and it would take place as a West German annexation of the East. March 1990 was a decisive pivot for Germany’s “internal” unification process. What diplomatically were called the “external” aspects of unification remained unsettled. These “external” aspects included more than half a million foreign troops deployed in the two Germanies under rights that dated back to the powers the victors had given themselves as occupiers in 1945. There had never been a German peace treaty that wrapped up and put aside those old powers. Though it is difficult for 21st century readers to comprehend, in early 1990 Germany was still the most heavily militarized area of real estate on the entire planet. -

REPORT 2019 at POINTS of LIGHT, We Believe That the Most Powerful Force of Change in Our World Is the Individual — One Who Makes a Positive Difference

ANNUAL REPORT 2019 AT POINTS OF LIGHT, we believe that the most powerful force of change in our world is the individual — one who makes a positive difference. We are a nonpartisan organization that inspires, equips and connects nonprofits, businesses and individuals ready to apply their time, talent, voice and resources to solve society’s greatest challenges. And we believe every action, no matter how small, can have an impact and change a life. Points of Light is committed to empowering, connecting and engaging people and organizations with opportunities to make a difference that are personal and meaningful. With our global network, we partner with corporations to help them become leaders in addressing challenges and encouraging deeper civic engagement that our society needs. Together, we are a force that transforms the world. O Z A T I N S B U S I N I N E A S S G E R S O T C 173 A Global Network 262 P Affiliates Businesses Engaged M I Per Year 37 41 L Countries U.S. States A I 57,000 C Local Community O Partners 3 million S Employees Mobilized Through Business Partners Per Year OUR GLOBAL 2 million People Engaged IMPACT Per Year Points of Light is committed to empowering, connecting and engaging people and organizations 1.9 million with opportunities to make a President’s Volunteer 6,500+ Service Awards difference that are meaningful and Daily Point impactful. Together with our Points of Light Awards of Light Global Network, we partner with social impact organizations, businesses and individuals to create 1,300+ UK and Commonwealth a global culture of volunteerism and Point of civic engagement. -

George W Bush Childhood Home Reconnaissance Survey.Pdf

Intermountain Region National Park Service U.S. Department of the Interior August 2015 GEORGE W. BUSH CHILDHOOD HOME Reconnaissance Survey Midland, Texas Front cover: President George W. Bush and First Lady Laura Bush speak to the media after touring the President’s childhood home at 1421 West Ohio Avenue, Midland, Texas, on October 4, 2008. President Bush traveled to attend a Republican fundraiser in the town where he grew up. Photo: SAUL LOEB/AFP/Getty Images CONTENTS BACKGROUND AND PURPOSE — i SUMMARY OF FINDINGS — iii RECONNAISSANCE SURVEY PROCESS — v NPS CRITERIA FOR EVALUATION OF NATIONAL SIGNIFICANCE — vii National Historic Landmark Criterion 2 – viii NPS Theme Studies on Presidential Sites – ix GEORGE W. BUSH: A CHILDHOOD IN MIDLAND — 1 SUITABILITY — 17 Childhood Homes of George W. Bush – 18 Adult Homes of George W. Bush – 24 Preliminary Determination of Suitability – 27 HISTORY AND DESCRIPTION OF THE GEORGE W. BUSH CHILDHOOD HOME, MIDLAND TEXAS — 29 Architectural Description – 29 Building History – 33 FEASABILITY AND NEED FOR NPS MANAGEMENT — 35 Preliminary Determination of Feasability – 37 Preliminary Determination of Need for NPS Management – 37 CONCLUSION AND RECOMMENDATIONS — 39 APPENDIX: THE 41ST AND 43RD PRESIDENTS AND FIRST LADIES OF THE UNITED STATES — 43 George H.W. Bush – 43 Barbara Pierce Bush – 44 George W. Bush – 45 Laura Welch Bush – 47 BIBLIOGRAPHY — 49 SURVEY TEAM MEMBERS — 51 George W. Bush Childhood Home Reconnaissance Survey George W. Bush’s childhood bedroom at the George W. Bush Childhood Home museum at 1421 West Ohio Avenue, Midland, Texas, 2012. The knotty-pine-paneled bedroom has been restored to appear as it did during the time that the Bush family lived in the home, from 1951 to 1955. -

JAMES A. BAKER, III the Case for Pragmatic Idealism Is Based on an Optimis- Tic View of Man, Tempered by Our Knowledge of Human Imperfection

Extract from Raising the Bar: The Crucial Role of the Lawyer in Society, by Talmage Boston. © State Bar of Texas 2012. Available to order at texasbarbooks.net. TWO MOST IMPORTANT LAWYERS OF THE LAST FIFTY YEARS 67 concluded his Watergate memoirs, The Right and the Power, with these words that summarize his ultimate triumph in “raising the bar”: From Watergate we learned what generations before us have known: our Constitution works. And during the Watergate years it was interpreted again so as to reaffirm that no one—absolutely no one—is above the law.29 JAMES A. BAKER, III The case for pragmatic idealism is based on an optimis- tic view of man, tempered by our knowledge of human imperfection. It promises no easy answers or quick fixes. But I am convinced that it offers our surest guide and best hope for navigating our great country safely through this precarious period of opportunity and risk in world affairs.30 In their historic careers, Leon Jaworski and James A. Baker, III, ended up in the same place—the highest level of achievement in their respective fields as lawyers—though they didn’t start from the same place. Leonidas Jaworski entered the world in 1905 as the son of Joseph Jaworski, a German-speaking Polish immigrant, who went through Ellis Island two years before Leon’s birth and made a modest living as an evangelical pastor leading small churches in Central Texas towns. James A. Baker, III, entered the world in 1930 as the son, grand- son, and great-grandson of distinguished lawyers all named James A. -

Four Points of Light in Tribute to George Herbert Walker Bush Chanukah 5779

Four Points of Light In Tribute to George Herbert Walker Bush Chanukah 5779 As we spent each night this week kindling the exquisite Chanukah candles, it seemed fitting that the nation was remembering George Herbert Walker Bush, who spoke of one thousand points of light. I must admit something of a personal connection to our nation’s forty first president, as, just three days following my fourth birthday, President Bush was the very first public official for whom I cast a vote. Before panicking that those persistent rumors of massive voter fraud are correct, allow me to explain. My parents were on opposite sides of that particular election- I shall not divulge who voted for whom- but I accompanied one of my parents to the voting booth on that Tuesday morning at the Whittier school. I had been given a choice as to which parent I would join, and so, I, knowing my parents divergence on this issue, was left to choose between the Vice President and Governor Dukakis. I chose the right parent, and felt extremely vindicated on Wednesday morning, when my parents told me that the Vice President would become President in just over two months. Not fully understanding the electoral college and its nuances at that stage of my life, and not realizing that Bush carried the state of New Jersey by over 420,000 votes, I was more or less convinced that my choice had been decisive. Shabbat, Chanukah, and Rosh Chodesh, independently, are all days on which we do not eulogize. But, that does not absolve of us of a dual ,חלקו כבוד למלכות ,obligation, both to show respect to national leadership 1 and, to learn the lessons of, whether or not one agreed with his policies, or supported his platform, the life of a remarkable person, not perfect, as no man is, but someone who embodied a time not of politics, but of public service.