Crow's Shadow Institute of the Arts

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Contact My IAIA

4/15/2015 Marie Watt | IAIA Contact My IAIA IAIA CLE ABOUT HOME VISIT EXHIBITIONS COLLECTION VISION PROJECT GIVING MUSEUM NEWS SEARCH MARIE WATT Vision Project Artists By Gail Tremblay Authors Marie Watt is an artist of Seneca, Scottish, and German ancestry. Manifestations Her art explores the confluence of myth, history and memory Curriculum Guide drawing from ancient and modern stories. In her most recent body of work, she employs the blanket as both material and metaphor. Used as gifts at naming ceremonies and memorials, blankets have a particular set of meanings in the American Indian community making their use as an art material particularly evocative. Watt conceives of blankets as both wall‐related, two‐dimensional objects that can be stitched to create tapestry—as in Ballad of Ira Hayes (2008)—or as materials that can be piled on pedestals between floor and ceiling as in Blanket Stories: Three Sisters, Cousin Rose, Four Pelts, and Sky Woman (2005). Ballad of Ira Hayes honors the Pima World War II veteran, placing his face before a symbol of his people—the man in the maze. In the lower right hand corner the viewer can see the portraits of the four other marines and the navy corpsman that raised the United States flag over Mt. Suribachi on Iwo Jima with Hayes. The use of army blankets as one of the materials for the piece adds a nuanced meaning. Blankets can also be slit and sewn into webs to create large three‐ Blanket Stories: Three Sisters, Cousin Rose, Four Pelts, and Sky Woman (detail), 2005, Stacked and folded wool dimensional objects like her dynamic work, Forget‐me‐not: blankets, salvaged cedar, Approx. -

In Conversation with Marie Watt: a New Coyote Tale by Marie Watt / October 19, 2017 / Current Issue, Features, Highlighted Content

Contemporary Projects A PUBLICATION OF Texts + Documents Conversations Search News + Notes About Art Journal Submissions « Previous / Next » In Conversation with Marie Watt: A New Coyote Tale By Marie Watt / October 19, 2017 / Current Issue, Features, Highlighted Content — Installation view, Unsuspected Possibilities: Leonardo Drew, Sarah Oppenheimer, and Marie Watt, 2015, SITE Santa Fe, July 2015–January 2016 (artwork © Marie Watt; photograph by Kate Russell, provided by SITE Santa Fe) The gallery, with installations by the three artists, was configured to evoke the footprint of a longhouse, a form of architecture built by the Haudenosaunee (Iroquois Nation). “I made my piece in collaboration with the Santa Fe Indian School, Santa Fe University of Art and Design, Tierra Encantada High School, Institute of American Indian Arts, and other members of the Santa Fe community. I was initially inspired by research into the Mohawk ironworkers who built many of Manhattan’s skyscrapers, an abstract correlation between the structure of the longhouse and the structure of the skyscraper, and the dense living communities and neighborliness that result from both.” Marie Watt first encountered Joseph Beuys’s work as a college student studying abroad. While working on an MFA at Yale, she wrote a reflection on the artist’s I Like America and America Likes Me from the perspective of Coyote, for a course taught by the art historian Romy Golan. In Beuys’s infamous 1974 performance, the German artist spent several days in an enclosed space at New York’s René Block Gallery with a live coyote, a large piece of wool felt, straw, gloves, a shepherd’s staff, and fifty copies of the Wall Street Journal, delivered daily during the performance. -

2017 Oregon Governor's Arts Awards Program

GOVERNOR’S ARTS AWARDS FRIDAY, OCTOBER , MESSAGE FROM THE GOVERNOR KATE BROWN Governor Dear Arts Supporters, I am honored to welcome you to the 2017 Governor’s Arts Awards. The Oregon Arts Commission has made sure art is a part of our daily lives for the past 50 years. In honor of this historic anniversary, I am proud to reinstate the Governor’s Arts Awards and to once again honor artists and organizations that make outstanding contributions to the arts in Oregon. Art is a fundamental ingredient of any thriving and vibrant community. Art sparks connections between people, movements and new ideas. Here in Oregon, the arts enrich our quality of life and local economies, helping form our great state’s unique identity. Not only that, art education is key in fostering a spirit of creativity and innovation in our youth. I want to thank each of you for being a part of this community, making Oregon more beautiful, more alive every day. Each of today’s Arts Awards recipients has touched the lives of thousands of Oregonians in meaningful ways. They were selected through a highly competitive process from a field of 110 worthy nominees and are extremely deserving of this honor. I thank them for making Oregon a better and more beautiful place and ask you to join with me in celebrating their achievements. Sincerely, Governor Kate Brown PROGRAM WELCOME Christopher Acebo • Chair, Oregon Arts Commission PERFORMANCE BRAVO Youth Orchestras & Darrell Grant AWARDS Presented by Governor Kate Brown COMMUNITY AWARD Crow’s Shadow Institute of the Arts LIFETIME ACHIEVEMENT AWARD Arvie Smith PHILANTHROPY AWARD The James F. -

Marie Watt: Lodge

Marie Watt: Lodge Hallie Ford Museum of Art at Willamette University February 4 – April 1, 2012 Teachers Guide This guide is to help teachers prepare students for a field trip to the exhibition, Marie Watt: Lodge and offer ideas for leading self-guided groups through the galleries. Teachers, however, will need to consider the level and needs of their students in adapting these materials and lessons. Goals • To introduce students to the work of Marie Watt • To explore the aesthetics and meaning of the materials the artist uses • To explore the idea of community in Watt’s work • To explore the idea of memory and storytelling in Watt’s work Objectives Students will be able to: • Discuss Marie Watt’s use of blankets, their aesthetic qualities, and their many associations • Discuss the various ways in which Watt engages a variety of communities in the creation of her work • Discuss the role of memory, both individual and collective, in Watt’s work and the objects she uses, and the role storytelling plays in sharing these memories • Reflect upon their own stories and create works that express them INDEX INTRODUCTION by Rebecca Dobkins ……………………………………………3 BEFORE THE MUSEUM VISIT: Dwelling ………………………………………4 AT THE MUSEUM (for self-guided tours)………………………………...………7 AFTER THE MUSEUM VISIT: Stadium................................................................8 RESOURCE ………………………………………………………………………….10 COMMON CURRICULUM GOALS ………………………………………………11 IMAGES: Dwelling and Stadium (with details) …………………………………...12 2 INTRODUCTION Rebecca Dobkins, Professor of Anthropology and Faculty Curator of Native American Art A lodge is a space of welcome; at its center is a hearth, a place where stories are shared. A blanket becomes a lodge, a cave, a fort. -

2 5 15 Diker ERG Final.Pdf

EDUCATOR RESOURCE GUIDE These materials are a resource for educators visiting the exhibition Indigenous Beauty: Masterworks of American Indian Art from the Diker Collection in a guided or self–guided visit. Educators are encouraged to develop open–ended discussions that ask for a wide range of opinions and expressions from students. The activities in this guide connect to core curriculum subject areas and can be adapted for grades K-12 to meet Washington State, Common Core Standards of Learning, and National Core Arts Standards, as well as 21st Century Learning Skills. Lessons incorporate a range of subject areas including science, math, art, social studies, and geography. Glossary words are in BOLD and related images for each project are included at the end of this guide. For assistance modifying these projects to fit your classroom curriculum, please email SAM’s Ann P. Wyckoff Teacher Resource Center (TRC) at [email protected]. Additional information for Indigenous Beauty can be found at www.seattleartmuseum.org/exhibitions/indigenous. For more information about bringing a group to SAM please visit seattleartmuseum.org/educators or email [email protected]. Comprising over 400 objects, Charles and Valerie Diker’s collection of Native American art offers a comprehensive overview of a diverse visual language of North American indigenous cultures. This exhibition examines each object’s wider cultural context and focuses on the themes of diversity, beauty, and knowledge. Each object holds the weight of time, place and symbolism, offering gateways for deeper discussion. Drawn from Indigenous Beauty and objects in SAM’s collection, the selections in this guide, Indigenous Beauty: Masterworks of American Indian Art from the Diker Collection: A Visual History, highlight the similarities and differences of art found in SAM’s strong Pacific Northwest Native collection and objects created throughout the rest of North America. -

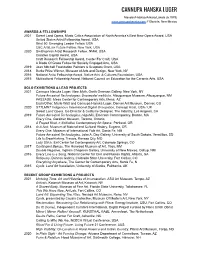

CV. Cannupa Hanska Luger Updated 08.2021

CANNUPA HANSKA LUGER Mandan/Hidatsa/Arikara/Lakota (b.1979) www.cannupahanska.com // Glorieta, New Mexico AWARDS & FELLOWSHIPS 2021 Sweet Land Opera, Music Critics Association of North America’s Best New Opera Award, USA United States Artist Fellowship Award, USA Grist 50: Emerging Leader Fellow, USA CEC ArtsLink Future Fellow, New York, USA 2020 Smithsonian Artist Research Fellow, NMAI, USA Creative Capital Award, USA Craft Research Fellowship Award, Center For Craft, USA A Blade Of Grass Fellow for Socially Engaged Arts, USA 2019 Joan Mitchell Foundation Painters & Sculptors Grant, USA 2018 Burke Prize Winner, Museum of Arts and Design, New York, NY 2016 National Artist Fellowship Award, Native Arts & Cultures Foundation, USA 2015 Multicultural Fellowship Award, National Council on Education for the Ceramic Arts, USA SOLO EXHIBITIONS & LEAD PROJECTS 2021 Cannupa Hanska Luger: New Myth, Garth Greenan Gallery, New York, NY Future Ancestral Technologies: Unziwoslal wašičuta, Albuquerque Museum, Albuquerque, NM PASSAGE, Mesa Center for Contemporary Arts, Mesa, AZ Each/Other: Marie Watt and Cannupa Hanska Luger, Denver Art Museum, Denver, CO 2020 STTLMNT Indigenous International Digital Occupation, Concept Artist, USA / UK Sweet Land Opera, Co-Director & Costume Designer, The Industry, Los Angeles, CA 2019 Future Ancestral Technologies: nágshibi, Emerson Contemporary, Boston, MA Every One, Gardiner Museum, Toronto, Ontario A Frayed Knot, c:3Initiative Contemporary Art Space, Portland, OR 2018 Ar-ti-fact, Museum of Natural and Cultural History, -

Contemporary Connections Teacher Guide

CONTEMPORARY CONNECTIONS Teacher Guide CONTEMPORARY CONNECTIONS Introduction Artworks made by Native American artists, inspired by Native cultures, and portraying Native individuals appear throughout Tacoma Art Museum’s collections and exhibitions. These objects affirm the continued presence and influence of Indigenous peoples in our communities and in mainstream culture. These contemporary artworks highlight the innovation of Native peoples in the present. There are also artworks created by non-Natives that can help us facilitate important dialogues on stereotypes and misrepresentations. Native Art Past and Present There are currently 567 federally recognized Native American tribes. Each tribe is unique with its own language, stories, belief systems, art, and cultural identity. Although art forms and styles vary from region to region and tribe to tribe, historically many Native peoples integrated design into daily life. Beauty was incorporated in utensils, tools, clothing, shelter, religious objects, and everything in between. Art served not only an aesthetic purpose, but was simultaneously spiritual and utilitarian. Native peoples mastered varying combinations of abstraction and figuration. Natural materials from the environment were used as well as foreign materials traded from far away tribes and eventually settlers from across the ocean. Today Native artists continue to adapt, utilizing contemporary resources, as they reflect on their personal experience and Native identity. The Pacific Northwest region has a large population of Native peoples with rich contemporary arts and cultures. Washington is home to 29 local tribes. Major cities, like most urban centers, also host individuals from a wide diversity of varying tribes representing cultures from the Plains, Southwest, Woodlands, Northeast, Great Lakes, and other regions. -

Portland Community College Art Program Review

Portland Community College Art Program Review March 2018 1 Table of Contents Click Section Title to Jump to that Section 1. Introduction and Overview 3 2. Outcomes and Assessment 8 3. Other Instructional Issues 11 4. Needs of Students and the Community 18 5. Faculty 27 6. Facilities, Instructional and Student Support 33 7. (no section for LDC programs) 8. Recommendations 41 Appendix Appendix 1: Art Beat Appendix 2: Core Outcomes Mapping Matrix Appendix 3: Enrollment Numbers Appendix 4: PCC Campus Art Galleries Appendix 5: Portland Women in the Arts Lecture Series Appendix 6: Guide for an Aide to a Low/No-Vision Student Appendix 7: Faculty Participation in Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion Appendix 8: Faculty Activities and Accomplishments 2 1. PROGRAM/DISCIPLINE OVERVIEW: A. Goals and Objectives: The primary goal of the PCC Art Program is to provide a quality education in the visual arts to the college’s diverse student body. To achieve this goal, the program offers foundation-level concentrations in two distinct disciplines: studio art and art history. Both disciplines offer a wide range of courses that foster critical thinking, problem solving, and creativity by engaging with the visual record of human history from the prehistoric era to the contemporary world. The program brings diverse skills and sensibilities together to help facilitate an understanding of our world, both past and present, while seeking to engage with global cultures. For students planning to continue their arts education, the PCC program provides a solid base upon which to transfer to a four-year institution. For others, art courses are a key component of their general education, fulfilling needed transfer credits and electives. -

Oregon Arts Commission Awards Arts Acquisition Funds to Oregon Visual Arts Institutions Through Partnership with the Ford Family Foundation

For Immediate Release May 30, 2012 Contact: Meagan Atiyeh, 503-986-0084, [email protected] Christine D’Arcy, 503-986-0087, [email protected] Oregon Arts Commission Awards Arts Acquisition Funds to Oregon Visual Arts Institutions through Partnership with The Ford Family Foundation The Arts Commission awarded $64,450 in Arts Acquisition funds to five arts organizations through The Ford Family Foundation’s Art Acquisition Program. The Art Acquisitions, managed by the Arts Commission, provide resources to acquire seminal works by Oregon visual artists to Oregon visual art institutions with publicly accessible collections. The effort preserves public access to great works and supports the artists and the visual arts institutions that sustain their work through acquisition and exhibition. Awards were made to: Museum of Contemporary Craft, Portland $40,000 for the acquisition of Betty Feves (1918-1995), Garden Wall, 1979. This work is currently on view in Generations: Betty Feves through July 28, and is being purchased from the Feves Family Collection. As one of the first Oregonians to receive the Governor’s Art Award in 1978, Betty Feves belonged to a generation of mid-century vanguard artists who set the stage for shifts in the use of clay in art. Feves’ work subverts the male-dominated field of post-WWII and is marked by her discovery of clay as an expressive art form during a time when most women studied art as a hobby. Academically trained in late 1930s, Feves lived, worked, and raised her children in Pendleton, Oregon where she remained for 40 years. -

Many Wests: Artists Shape an American Idea

Many Wests: Artists Shape an American Idea Many Wests: Artists Shape an American Idea July 31, 2021 - February 13, 2022 Ideas about the American West, both in the popular imagination and in commonly accepted historical narratives, are often based on a past that never was, and fail to take into account important events that actually occurred. At once, “The West” can conjure images of rugged colonial settlers, gun-toting-cowboys, or vacant expanses of natural beauty. Many Wests: Artists Shape an American Idea offers multiple views of “The West” through the perspectives of forty-eight modern and contemporary artists. Their artworks question old and racist clichés, examine tragic and marginalized histories, and illuminate the many communities and events that continue to form this region of the United States. The exhibition explores the specific ways artists actively shape our understanding of the life, history and myths of the American West. National Tour Many Wests features artwork from the permanent collections of the Smithsonian American Art Museum and four partner museums located in some of the fastest- growing cities and states in the western region of the United States. The collaborating partner museums are the Boise Art Museum in Idaho; the Jordan Schnitzer Museum of Art in Eugene, Oregon; the Utah Museum of Fine Arts in Salt Lake City; and the Whatcom Museum in Bellingham, Washington. It is the culmination of a multi-year, joint curatorial initiative made possible by the Art Bridges Foundation. This is one in a series of American art exhibitions created through a multi-year, multi-institutional partnership formed by the Smithsonian American Art Museum as part of the Art Bridges Initiative. -

Marie Watt's Forget-Me-Not: Stitched in Wool, a More Human War Memorial

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Textile Society of America Symposium Proceedings Textile Society of America 9-2012 Marie Watt's Forget-me-not: Stitched in Wool, a More Human War Memorial Rebecca Head Trautmann Smithsonian's National Museum, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/tsaconf Head Trautmann, Rebecca, "Marie Watt's Forget-me-not: Stitched in Wool, a More Human War Memorial" (2012). Textile Society of America Symposium Proceedings. 750. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/tsaconf/750 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Textile Society of America at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Textile Society of America Symposium Proceedings by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. Marie Watt's Forget-me-not: Stitched in Wool, a More Human War Memorial Rebecca Head Trautmann [email protected] In large wall tapestries, towering blanket stacks, small stitched samplers, and complex installations, Marie Watt evokes the personal and collective memories embodied in wool blankets. The artist employs old—or “reclaimed”—blankets that are worn with use, faded in color, and stretched out of shape to call forth the stories and histories these humble objects carry.1 Watt’s 2008 work Forget-me-not: Mothers and Sons is an installation piece memorializing soldiers killed in the Iraq and Afghanistan wars. Wishing to humanize the stories of soldiers from the Pacific Northwest, many of them very young, who had lost their lives, Watt created a series of memorial portraits, hand-stitched using wool blankets. -

MARC STRAUS Gallery

MARC STRAUS NEW YORK Marie Watt b. 1967, Seattle, Washington, US Education 1996 MFA, Painting & Printmaking Yale University School of Art New Haven, CT 1992 AFA, Museum Studies Institute of American Indian Arts Santa Fe, NM 1990 BS, Speech Communications & Art Willamette University Salem, OR Solo Exhibitions 2021 Marie Watt, Hunterdon Art Museum, Clinton, New Jersey Marie Watt Prints, Touring print show organized by Jordan Schnitzer and His Family Foundations in partnership with the University of San Diego 2020 Turtle Island, MARC STRAUS GALLERY, New York, NY 2018 Companion Species Calling Companion Species, Greg Kucera Gallery, Seattle, WA Companion Species (Underbelly), Jordan Schnitzer Museum of Art, Washington State University, Pullman, WA, Curated by Ryan Hardesty 2017 The Western Door, The Rockwell Museum, Corning, NY, Curated by Jennifer Kramer Companion Species, PDX Contemporary Art, Portland, OR 2016 Blanket Stories: Textile Society, R.R. Stewart, Ancient One, United States Embassy, Islamabad, Pakistan, Permanent installation Witness, Bertha V.B. Lederer Gallery, SUNY Geneseo, Geneseo, NY 2014 Blanket Stories: Transportation Object, Generous Ones, Trek, Tacoma Art Museum, Tacoma, WA, Permanent installation Receiver, Greg Kucera Gallery, Seattle, WA Receiver, C.N. Gorman Museum at the University of California at Davis, Davis, CA 2012 Skywalker/Skyscraper, PDX Contemporary Art, Portland, OR Cradle, Greg Kucera Gallery, Seattle, WA Lodge, Hallie Ford Museum of Art, Salem, OR; Tacoma Art Museum, Tacoma, WA 2011 Counting Coup Museum