Dietary Gluten-Induced Gut Dysbiosis Is Accompanied by Selective

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Mobile Genetic Elements in Streptococci

Curr. Issues Mol. Biol. (2019) 32: 123-166. DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.21775/cimb.032.123 Mobile Genetic Elements in Streptococci Miao Lu#, Tao Gong#, Anqi Zhang, Boyu Tang, Jiamin Chen, Zhong Zhang, Yuqing Li*, Xuedong Zhou* State Key Laboratory of Oral Diseases, National Clinical Research Center for Oral Diseases, West China Hospital of Stomatology, Sichuan University, Chengdu, PR China. #Miao Lu and Tao Gong contributed equally to this work. *Address correspondence to: [email protected], [email protected] Abstract Streptococci are a group of Gram-positive bacteria belonging to the family Streptococcaceae, which are responsible of multiple diseases. Some of these species can cause invasive infection that may result in life-threatening illness. Moreover, antibiotic-resistant bacteria are considerably increasing, thus imposing a global consideration. One of the main causes of this resistance is the horizontal gene transfer (HGT), associated to gene transfer agents including transposons, integrons, plasmids and bacteriophages. These agents, which are called mobile genetic elements (MGEs), encode proteins able to mediate DNA movements. This review briefly describes MGEs in streptococci, focusing on their structure and properties related to HGT and antibiotic resistance. caister.com/cimb 123 Curr. Issues Mol. Biol. (2019) Vol. 32 Mobile Genetic Elements Lu et al Introduction Streptococci are a group of Gram-positive bacteria widely distributed across human and animals. Unlike the Staphylococcus species, streptococci are catalase negative and are subclassified into the three subspecies alpha, beta and gamma according to the partial, complete or absent hemolysis induced, respectively. The beta hemolytic streptococci species are further classified by the cell wall carbohydrate composition (Lancefield, 1933) and according to human diseases in Lancefield groups A, B, C and G. -

Validation of the Asaim Framework and Its Workflows on HMP Mock Community Samples

Validation of the ASaiM framework and its workflows on HMP mock community samples The ASaiM framework and its workflows have been tested and validated on two mock metagenomic data of an artificial community (with 22 known microbial strains). The datasets are available on EBI metagenomics database (project accession number: SRP004311). First we checked that the targeted abundances (based on number of PCR product) from both mock datasets were similar to the effective abundance (by mapping reads on reference genomes). Second, taxonomic and functional results produced by the ASaiM framework have been extensively analyzed and compared to expectations and to results obtained with the EBI metagenomics pipeline (S. Hunter et al. 2014). For these datasets, the ASaiM framework produces accurate and precise taxonomic assignations, different functional results (gene families, pathways, GO slim terms) and results combining taxonomic and functional information. Despite almost 1.4 million of raw metagenomic sequences, these analyses were executed in less than 6h on a commodity computer. Hence, the ASaiM framework and its workflows are proven to be relevant for the analysis of microbiota datasets. 1Data On EBI metagenomics database, two mock community samples for Human Microbiome Project (HMP) are available. Both samples contain a genomic mixture of 22 known microbial strains. Relative abundance of each strain has been targeted using the number of PCR product of their respective 16S sequences (Table 1). In first sample (SRR072232), the targeted 16S copies of the strains vary by up to four orders of magnitude between the strains (Table 1), whereas in second sample (SRR072233) the same 16S copy number is targeted for each strain (Table 1). -

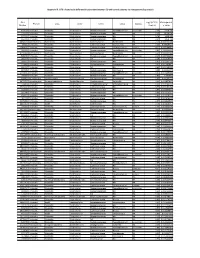

Appendix III: OTU's Found to Be Differentially Abundant Between CD and Control Patients Via Metagenomeseq Analysis

Appendix III: OTU's found to be differentially abundant between CD and control patients via metagenomeSeq analysis OTU Log2 (FC CD / FDR Adjusted Phylum Class Order Family Genus Species Number Control) p value 518372 Firmicutes Clostridia Clostridiales Ruminococcaceae Faecalibacterium prausnitzii 2.16 5.69E-08 194497 Firmicutes Clostridia Clostridiales Ruminococcaceae NA NA 2.15 8.93E-06 175761 Firmicutes Clostridia Clostridiales Ruminococcaceae NA NA 5.74 1.99E-05 193709 Firmicutes Clostridia Clostridiales Ruminococcaceae NA NA 2.40 2.14E-05 4464079 Bacteroidetes Bacteroidia Bacteroidales Bacteroidaceae Bacteroides NA 7.79 0.000123188 20421 Firmicutes Clostridia Clostridiales Lachnospiraceae Coprococcus NA 1.19 0.00013719 3044876 Firmicutes Clostridia Clostridiales Lachnospiraceae [Ruminococcus] gnavus -4.32 0.000194983 184000 Firmicutes Clostridia Clostridiales Ruminococcaceae Faecalibacterium prausnitzii 2.81 0.000306032 4392484 Bacteroidetes Bacteroidia Bacteroidales Bacteroidaceae Bacteroides NA 5.53 0.000339948 528715 Firmicutes Clostridia Clostridiales Ruminococcaceae Faecalibacterium prausnitzii 2.17 0.000722263 186707 Firmicutes Clostridia Clostridiales NA NA NA 2.28 0.001028539 193101 Firmicutes Clostridia Clostridiales Ruminococcaceae NA NA 1.90 0.001230738 339685 Firmicutes Clostridia Clostridiales Peptococcaceae Peptococcus NA 3.52 0.001382447 101237 Firmicutes Clostridia Clostridiales NA NA NA 2.64 0.001415109 347690 Firmicutes Clostridia Clostridiales Ruminococcaceae Oscillospira NA 3.18 0.00152075 2110315 Firmicutes Clostridia -

Streptococcaceae

STREPTOCOCCACEAE Instructor Dr. Maytham Ihsan Ph.D Vet Microbiology 1 STREPTOCOCCACEAE Genus: Streptococcus and Enterocccus Streptococcus and Enterocccus genera, are Gram‐positive ovoid (lanceolate) cocci, approximately 1 μm in diameter, that tend to occur in singles, pairs & chains (rosary‐like) may be long or short. Streptococcus species occur as commensals on skin, upper & lower respiratory tract and mucous membranes; some may act as opportunistic pathogens causing pyogenic infections. Enteroccci spp. are enteric opportunistic & can be found in the intestinal tract of many animlas & humans. Growth & Culture Characteristics • Most streptococci are facultative anaerobes and catalase‐negative. • They are non‐motile and oxidase‐negative and do not form spores & susceptible to desiccation. • They are fastidious bacteria and require the addition of blood or serum to culture media. They grow at temperature ranging from 37°C to 42°C. Group D (Enterocooci), are considered thermophilic & can gorw at 45°C or even higher. • Colonies are small about 1 mm in size, smooth, translucent & may be greyish. • Streptococcus pneumoniae (pneumococcus or diplococcus) occurs as slightly pear‐shaped cocci in pairs. Pathogenic strains have thick capsules and produce mucoid colonies or flat colonies with smooth borders & a central concavity “draughtsman colonies” aer 48‐72 hrs on blood agar. These bacteria cause pneumonia in humans and rats. 2 • Some of streptococci grow on MacConkey like: Enterococcus faecalis, Strept. bovis, Sterpt. uberis & strept. lactis producing very tiny colonies like pin‐point appearance aer 48 hrs of incubaon at 37°C. • Streptococci genera grow slowly in broth media, sometimes forming faint opacity; whereas others with a fluffy deposit adherent to the side of the tube. -

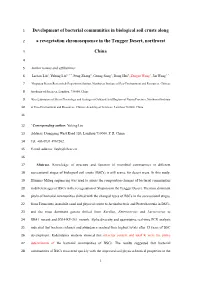

Development of Bacterial Communities in Biological Soil Crusts Along

1 Development of bacterial communities in biological soil crusts along 2 a revegetation chronosequence in the Tengger Desert, northwest 3 China 4 5 Author names and affiliations: 6 Lichao Liu1, Yubing Liu1, 2 *, Peng Zhang1, Guang Song1, Rong Hui1, Zengru Wang1, Jin Wang1, 2 7 1Shapotou Desert Research & Experiment Station, Northwest Institute of Eco-Environment and Resources, Chinese 8 Academy of Sciences, Lanzhou, 730000, China 9 2Key Laboratory of Stress Physiology and Ecology in Cold and Arid Regions of Gansu Province, Northwest Institute 10 of Eco–Environment and Resources, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Lanzhou 730000, China 11 12 * Corresponding author: Yubing Liu 13 Address: Donggang West Road 320, Lanzhou 730000, P. R. China. 14 Tel: +86 0931 4967202. 15 E-mail address: [email protected] 16 17 Abstract. Knowledge of structure and function of microbial communities in different 18 successional stages of biological soil crusts (BSCs) is still scarce for desert areas. In this study, 19 Illumina MiSeq sequencing was used to assess the composition changes of bacterial communities 20 in different ages of BSCs in the revegetation of Shapotou in the Tengger Desert. The most dominant 21 phyla of bacterial communities shifted with the changed types of BSCs in the successional stages, 22 from Firmicutes in mobile sand and physical crusts to Actinobacteria and Proteobacteria in BSCs, 23 and the most dominant genera shifted from Bacillus, Enterococcus and Lactococcus to 24 RB41_norank and JG34-KF-361_norank. Alpha diversity and quantitative real-time PCR analysis 25 indicated that bacteria richness and abundance reached their highest levels after 15 years of BSC 26 development. -

Molecular Mechanisms of Inhibition of Streptococcus Species by Phytochemicals

molecules Review Molecular Mechanisms of Inhibition of Streptococcus Species by Phytochemicals Soheila Abachi 1, Song Lee 2 and H. P. Vasantha Rupasinghe 1,* 1 Faculty of Agriculture, Dalhousie University, Truro, NS PO Box 550, Canada; [email protected] 2 Faculty of Dentistry, Dalhousie University, Halifax, NS PO Box 15000, Canada; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +1-902-893-6623 Academic Editors: Maurizio Battino, Etsuo Niki and José L. Quiles Received: 7 January 2016 ; Accepted: 6 February 2016 ; Published: 17 February 2016 Abstract: This review paper summarizes the antibacterial effects of phytochemicals of various medicinal plants against pathogenic and cariogenic streptococcal species. The information suggests that these phytochemicals have potential as alternatives to the classical antibiotics currently used for the treatment of streptococcal infections. The phytochemicals demonstrate direct bactericidal or bacteriostatic effects, such as: (i) prevention of bacterial adherence to mucosal surfaces of the pharynx, skin, and teeth surface; (ii) inhibition of glycolytic enzymes and pH drop; (iii) reduction of biofilm and plaque formation; and (iv) cell surface hydrophobicity. Collectively, findings from numerous studies suggest that phytochemicals could be used as drugs for elimination of infections with minimal side effects. Keywords: streptococci; biofilm; adherence; phytochemical; quorum sensing; S. mutans; S. pyogenes; S. agalactiae; S. pneumoniae 1. Introduction The aim of this review is to summarize the current knowledge of the antimicrobial activity of naturally occurring molecules isolated from plants against Streptococcus species, focusing on their mechanisms of action. This review will highlight the phytochemicals that could be used as alternatives or enhancements to current antibiotic treatments for Streptococcus species. -

Beta-Haemolytic Streptococci (BHS)

technical sheet Beta-Haemolytic Streptococci (BHS) Classification Transmission Gram-positive cocci, often found in chains Transmission is generally via direct contact with nasopharyngeal secretions from ill or carrier animals. Family Animals may also be infected by exposure to ill or Streptococcaceae carrier caretakers. β-haemolytic streptococci are characterized by Lancefield grouping (a characterization based on Clinical Signs and Lesions carbohydrates in the cell walls). Only some Lancefield In mice and rats, generally none. Occasional groups are of clinical importance in laboratory rodents. outbreaks of disease associated with BHS are Streptococci are generally referred to by their Lancefield reported anecdotally and in the literature. In most grouping but genus and species are occasionally used. cases described, animals became systemically ill after experimental manipulation, and other animals Group A: Streptococcus pyogenes in the colony were found to be asymptomatic Group B: Streptococcus agalactiae carriers. In a case report not involving experimental Group C: Streptococcus equi subsp. zooepidemicus manipulation, DBA/2NTac mice and their hybrids were Group G: Streptococcus canis more susceptible to an ascending pyelonephritis and subsequent systemic disease induced by Group B Affected species streptococci than other strains housed in the same β-haemolytic streptococci are generally considered barrier. opportunists that can colonize most species. Mice and guinea pigs are reported most frequently with clinical In guinea pigs, infection with Group C streptococci signs, although many rodent colonies are colonized leads to swelling and infection of the lymph nodes. with no morbidity, suggesting disease occurs only with Guinea pigs can be inapparent carriers of the organism severe stress or in other exceptional circumstances. -

Multi-Product Lactic Acid Bacteria Fermentations: a Review

fermentation Review Multi-Product Lactic Acid Bacteria Fermentations: A Review José Aníbal Mora-Villalobos 1 ,Jéssica Montero-Zamora 1, Natalia Barboza 2,3, Carolina Rojas-Garbanzo 3, Jessie Usaga 3, Mauricio Redondo-Solano 4, Linda Schroedter 5, Agata Olszewska-Widdrat 5 and José Pablo López-Gómez 5,* 1 National Center for Biotechnological Innovations of Costa Rica (CENIBiot), National Center of High Technology (CeNAT), San Jose 1174-1200, Costa Rica; [email protected] (J.A.M.-V.); [email protected] (J.M.-Z.) 2 Food Technology Department, University of Costa Rica (UCR), San Jose 11501-2060, Costa Rica; [email protected] 3 National Center for Food Science and Technology (CITA), University of Costa Rica (UCR), San Jose 11501-2060, Costa Rica; [email protected] (C.R.-G.); [email protected] (J.U.) 4 Research Center in Tropical Diseases (CIET) and Food Microbiology Section, Microbiology Faculty, University of Costa Rica (UCR), San Jose 11501-2060, Costa Rica; [email protected] 5 Bioengineering Department, Leibniz Institute for Agricultural Engineering and Bioeconomy (ATB), 14469 Potsdam, Germany; [email protected] (L.S.); [email protected] (A.O.-W.) * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +49-(0331)-5699-857 Received: 15 December 2019; Accepted: 4 February 2020; Published: 10 February 2020 Abstract: Industrial biotechnology is a continuously expanding field focused on the application of microorganisms to produce chemicals using renewable sources as substrates. Currently, an increasing interest in new versatile processes, able to utilize a variety of substrates to obtain diverse products, can be observed. -

Annotations of the Otus with the Lowest P-Values for SR Samples at 0 and 4H Fermentation Time Points

Electronic Supplementary Material (ESI) for Food & Function. This journal is © The Royal Society of Chemistry 2016 Table S1. Taxonomic annotations: Annotations of the OTUs with the lowest p-values for SR samples at 0 and 4h fermentation time points. TAXA ID PHYLUM CLASS ORDER FAMILY GENUS SPECIES 4452633 Firmicutes Clostridia Clostridiales Clostridiaceae unclassified unclassified 191399 Firmicutes Clostridia Clostridiales Ruminococcaceae unclassified unclassified 4256470 Bacteroidetes Bacteroidia Bacteroidales Bacteroidaceae Bacteroides 97otu97833 179291 Firmicutes Clostridia Clostridiales Ruminococcaceae Faecalibacterium prausnitzii 192046 Firmicutes Clostridia Clostridiales unclassified unclassified unclassified 4315974 Firmicutes Bacilli Lactobacillales Streptococcaceae Streptococcus 97otu66887 4343627 Bacteroidetes Bacteroidia Bacteroidales Bacteroidaceae Bacteroides fragilis 760967 Bacteroidetes Bacteroidia Bacteroidales Prevotellaceae Prevotella 97otu12794 4475758 Firmicutes Clostridia Clostridiales Veillonellaceae Veillonella unclassified 566976 Bacteroidetes Gammapro Bacteroidales Bacteroidaceae Bacteroides unclassified teobacteria 328617 Bacteroidetes Bacteroidia Bacteroidales Bacteroidaceae Bacteroides uniformis 16054 Firmicutes Clostridia Clostridiales Ruminococcaceae Ruminococcus 97otu97520 SR: sun-dried raisins. Table S2. Taxonomic annotations: Annotations of the OTUs with the lowest p-values for SR samples at 0 and 8h fermentation time points. TAXA ID PHYLUM CLASS ORDER FAMILY GENUS SPECIES 194443 Firmicutes Clostridia Clostridiales -

Guide to Turning an RDP File Into a Data Set

Guide to Turning an RDP File into a Data Set Berkley Shands, Patricio S. La Rosa, Elena Deych, William Shannon July 5, 2017 Below we will define the basic steps required to generate a data set from an RDP file 1. Take an RDP file such as this example: ;Root:1.0;Bacteria:1.0;Firmicutes:1.0;Bacilli:1.0;Bacillales:1.0;Staphylococcaceae:1.0; ;Root:1.0;Bacteria:1.0;Firmicutes:1.0;Bacilli:1.0;Lactobacillales:1.0;Carnobacteriaceae:0.8; ;Root:1.0;Bacteria:1.0;Bacteroidetes:1.0;Bacteroidia:1.0;Bacteroidales:1.0;Prevotellaceae:1.0; ;Root:1.0;Bacteria:1.0;Bacteroidetes:1.0;Bacteroidia:1.0;Bacteroidales:1.0;Prevotellaceae:1.0; ;Root:1.0;Bacteria:1.0;Bacteroidetes:1.0;Bacteroidia:1.0;Unclassified:0.5;Unclassified:0.5; 2. Take the first entry and seperate each level into its own row, while seper- ating levels by a period: Root, 1 Root.Bacteria, 1 Root.Bacteria.Firmicutes, 1 Root.Bacteria.Firmicutes.Bacilli, 1 Root.Bacteria.Firmicutes.Bacilli.Bacillales, 1 Root.Bacteria.Firmicutes.Bacilli.Bacillales.Staphylococcaceae, 1 3. Do the same with each following row, adding to the number at the end if it is the same: Root, 5 Root.Bacteria, 5 Root.Bacteria.Firmicutes, 2 Root.Bacteria.Firmicutes.Bacilli, 2 Root.Bacteria.Firmicutes.Bacilli.Bacillales, 1 Root.Bacteria.Firmicutes.Bacilli.Bacillales.Staphylococcaceae, 1 Root.Bacteria.Firmicutes.Bacilli.Lactobacillales, 1 Root.Bacteria.Firmicutes.Bacilli.Lactobacillales.Carnobacteriaceae, .8 Root.Bacteria.Bacteroidetes, 3 Root.Bacteria.Bacteroidetes.Bacteroidia, 3 Root.Bacteria.Bacteroidetes.Bacteroidia.Bacteroidales, 2 Root.Bacteria.Bacteroidetes.Bacteroidia.Bacteroidales.Prevotellaceae, 2 Root.Bacteria.Bacteroidetes.Bacteroidia.Unclassified, .5 Root.Bacteria.Bacteroidetes.Bacteroidia.Unclassified.Unclassified, .5 4. -

Microbiological and Metagenomic Characterization of a Retail Delicatessen Galotyri-Like Fresh Acid-Curd Cheese Product

fermentation Article Microbiological and Metagenomic Characterization of a Retail Delicatessen Galotyri-Like Fresh Acid-Curd Cheese Product John Samelis 1,* , Agapi I. Doulgeraki 2,* , Vasiliki Bikouli 2, Dimitrios Pappas 3 and Athanasia Kakouri 1 1 Dairy Research Department, Hellenic Agricultural Organization ‘DIMITRA’, Katsikas, 45221 Ioannina, Greece; [email protected] 2 Hellenic Agricultural Organization ‘DIMITRA’, Institute of Technology of Agricultural Products, 14123 Lycovrissi, Greece; [email protected] 3 Skarfi EPE—Pappas Bros Traditional Dairy, 48200 Filippiada, Greece; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected] (J.S.); [email protected] (A.I.D.); Tel.: +30-2651094789 (J.S.); +30-2102845940 (A.I.D.) Abstract: This study evaluated the microbial quality, safety, and ecology of a retail delicatessen Galotyri-like fresh acid-curd cheese traditionally produced by mixing fresh natural Greek yogurt with ‘Myzithrenio’, a naturally fermented and ripened whey cheese variety. Five retail cheese batches (mean pH 4.1) were analyzed for total and selective microbial counts, and 150 presumptive isolates of lactic acid bacteria (LAB) were characterized biochemically. Additionally, the most and the least diversified batches were subjected to a culture-independent 16S rRNA gene sequencing analysis. LAB prevailed in all cheeses followed by yeasts. Enterobacteria, pseudomonads, and staphylococci were present as <100 viable cells/g of cheese. The yogurt starters Streptococcus thermophilus and Lactobacillus delbrueckii were the most abundant LAB isolates, followed by nonstarter strains of Lactiplantibacillus, Lacticaseibacillus, Enterococcus faecium, E. faecalis, and Leuconostoc mesenteroides, Citation: Samelis, J.; Doulgeraki, A.I.; whose isolation frequency was batch-dependent. Lactococcus lactis isolates were sporadic, except Bikouli, V.; Pappas, D.; Kakouri, A. Microbiological and Metagenomic for one cheese batch. -

Streptococcosis Humans and Animals

Zoonotic Importance Members of the genus Streptococcus cause mild to severe bacterial illnesses in Streptococcosis humans and animals. These organisms typically colonize one or more species as commensals, and can cause opportunistic infections in those hosts. However, they are not completely host-specific, and some animal-associated streptococci can be found occasionally in humans. Many zoonotic cases are sporadic, but organisms such as S. Last Updated: September 2020 equi subsp. zooepidemicus or a fish-associated strain of S. agalactiae have caused outbreaks, and S. suis, which is normally carried in pigs, has emerged as a significant agent of streptoccoccal meningitis, septicemia, toxic shock-like syndrome and other human illnesses, especially in parts of Asia. Streptococci with human reservoirs, such as S. pyogenes or S. pneumoniae, can likewise be transmitted occasionally to animals. These reverse zoonoses may cause human illness if an infected animal, such as a cow with an udder colonized by S. pyogenes, transmits the organism back to people. Occasionally, their presence in an animal may interfere with control efforts directed at humans. For instance, recurrent streptococcal pharyngitis in one family was cured only when the family dog, which was also colonized asymptomatically with S. pyogenes, was treated concurrently with all family members. Etiology There are several dozen recognized species in the genus Streptococcus, Gram positive cocci in the family Streptococcaceae. Almost all species of mammals and birds, as well as many poikilotherms, carry one or more species as commensals on skin or mucosa. These organisms can act as facultative pathogens, often in the carrier. Nomenclature and identification of streptococci Hemolytic reactions on blood agar and Lancefield groups are useful in distinguishing members of the genus Streptococcus.