Teaching African American Discourse: Lessons of a Recovering Segregationist

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Vulcan! Table of Contents

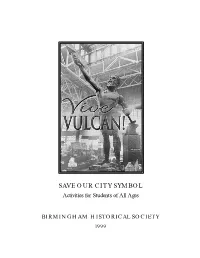

SAVE OUR CITY SYMBOL Activities for Students of All Ages BIRMINGHAM HISTORICAL SOCIETY 1999 VIVE VULCAN! TABLE OF CONTENTS Teacher Materials A. Overview D. Quiz & Answers B. Activity Ideas E. Word Search Key C. Questions & Answers F. Map of the Ancient World Key Activities 1. The Resumé of a Man of Iron 16. The Red Mountain Revival 2. Birmingham at the Turn 17. National Park Service of the 20th Century Documentation 3. The Big Idea 18. Restoring the Statue 4. The Art Scene 19. A Vision for Vulcan 5. Time Line 20. American Landmarks 6. Colossi of the Ancient World 21. Tallest American Monument 7. Map of the Ancient World 22. Vulcan’s Global Family 8. Vulcan’s Family 23. Quiz 9. Moretti to the Rescue 24. Word Search 10. Recipe for Sloss No. 2 25. Questions Pig Iron 26. Glossary 11. The Foundrymen’s Challenge 27. Pedestal Project 12. Casting the Colossus 28. Picture Page, 13. Meet Me in St. Louis The Birmingham News–Age Herald, 14. Triumph at the Fair Sunday, October 31, 1937 15. Vital Stats On the cover: VULCAN AT THE FAIR. Missouri Historical Society 1035; photographer: Dept. Of Mines & Metallurgy, 1904, St. Louis, Missouri. Cast of iron in Birmingham, Vulcan served as the Birmingham and Alabama exhibit for the St. Louis World’s Fair. As god of the forge, he holds a spearpoint he has just made on his anvil. The spearpoint is of polished steel. In a gesture of triumph, the colossal smith extends his arm upward. About his feet, piles of mineral resources extol Alabama’s mineral wealth and its capability of making colossal quantities of iron, such as that showcased in the statue, and of steel (as demonstrated with the spearpoint). -

Subarea 5 Master Plan Update March 2021

ATLANTA BELTLINE SUBAREA 5 MASTER PLAN UPDATE MARCH 2021 CONTENTS 1. Executive Summary 1 1.1 Overview 2 1.2 Community Engagement 4 2. Context 13 2.1 What is the Atlanta BeltLine? 14 2.2 Subarea Overview 16 3. The Subarea Today 19 3.1 Progress To-Date 20 3.2 Land Use and Design/Zoning 24 3.3 Mobility 32 3.4 Parks and Greenspace 38 3.5 Community Facilities 38 3.6 Historic Preservation 39 3.7 Market Analysis 44 3.8 Plan Review 49 4. Community Engagement 53 4.1 Overall Process 54 4.2 Findings 55 5. The Subarea of the Future 59 5.1 Goals & Principles 60 5.2 Future Land Use Recommendations 62 5.3 Mobility Recommendations 74 5.4 Parks and Greenspace Recommendations 88 5.5 Zoning and Policy Recommendations 89 5.6 Historic Preservation Recommendations 92 5.7 Arts and Culture Recommendations 93 Image Credits Cover image of Historic Fourth Ward Park playground by Stantec. All other images, illustrations, and drawings by Stantec or Atlanta BeltLine, Inc. unless otherwise noted. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY - iv Atlanta BeltLine Subarea 5 Master Plan — March 2021 SECTION HEADER TITLE - SECTION SUBHEADER INFORMATION 1 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 1 Report Title — Month, Year EXECUTIVE SUMMARY - OVERVIEW 1.1 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 1.1.1 OVERVIEW Subarea 5 has seen more development activity Looking forward to the next ten years, this plan than any subarea along the Atlanta BeltLine update identifies a series of recommendations over the past decade. The previous subarea plan and strategic actions that build on prior growth to was adopted by City Council in 2009, the same ensure that future development is in keeping with year construction started on the first phase of the community’s collective vision of the future. -

Unmasked· SN CC

John S. J(night The Atlanta Riot JOHN S. KNIGHT Unmasked·SN CC The recent rio ts in Atlanta has no more than 300 mem Confere nce, a Negro organiza- •• offer convincing evidence that bers. These have been the tion, denounced both SNICK · most, if . not all, of the racial agents of anarchy in Watts, and Carmichael, while calling New York, Chicago and other violence in our large cities bas for constructive measures de major cities . signed to alleviate problems been organized and led by a which directly concern the small minority bent upon the SNICK'S begin nin g were Negro. · destruction of our society. more auspicious. lts earl y stu My authority for this state dent leaders were motivated by D r. Martin Luther King, ment is Ralph McGill, pub high dedication to the civil president Roy Wilkins of the lisher of the Atlanta Constitu rights cause. Now the John NAACP and Whitney Young tion, long a moving and mili Lewises and other responsibles who heads the Urban League tant force for equal treatment are out. Control of SNICK is have all repudiated Stokely of the Negro citizen as pro held by the extreme radicals, Carmichael and his tactics. of whom Carmichael is the vided by law and the Con ATLANTA has long enjoyed dominating figu re. stitution of the United States. an enviable reputation for ra McGill places responsibility As McGill says, SNICK is cial amity. Ironically, it was for the Atlanta disturbances no longer a civil J ights organi Atlanta's splendid image that squarely upon the Student Non zation but an anarchistic group the destroyers sought to tar- • Violent Coordinating Commit which is openly and officially ni h. -

Birmingham Activities

Things to See and Do in Birmingham AL Sloss Furnace: National Histor- Ruffner Mountain: 1,038-acre urban Barber Museum is recognized by ic Landmark, offering guided & nature preserve. One of the largest Guinness World Records as the self tours. It is also a unique privately held urban nature pre- world’s largest motorcycle collection venue for events & concerts. serves in the United States. w/over 1,400 cycles over 100 years Railroad Park: beautiful 8-block Birmingham Zoo is Alabama's must Birmingham Botanical Gardens green space that celebrates the -see attraction, w/approx. 950 offers stunning glasshouses, industrial and artistic heritage animals of 230 species calling it beautiful gardens, playground, of downtown Birmingham. home. tearoom & gift shop over 15 acres. AL Jazz Hall of Fame: Honors ALA Sports Hall of Fame: More Birmingham Museum of Art is great jazz artists w/ties to Ala, than 5,000 sports artifacts are owned by the City of Birmingham furnishing educational info, displayed in this 33,000-sq-foot and encompasses 3.9 acres in the exhibits, & entertainment. home for heroes. heart of the city’s cultural district Arlington House & Gardens is on The Vulcan statue is the largest cast Rickwood's miracle mile of under- the National Register of Historic iron statue in the world, and is the ground caverns! The 260 million- year -old limestone formations, Places located on 6 acres in the city symbol of Birmingham, Alabama. heart of Old Elyton. blind cave fish & underground pools. Birmingham Civil Rights Insti- McWane Science Center in Birming- Rickwood Field, America's oldest tute: large interpretive museum ham features 4 floors of hands-on ballpark. -

Can the South Be Redeemed?

The Bitter Southerner Podcast: Can the South Be Redeemed? Chuck Reece (00:00:04): Hello again my friends and welcome to the final episode of The Bitter Southerner Podcast, second season. We are, as always, co-produced with the good people of Georgia Public Broadcasting and for our grand finale this season, we're going to attempt to answer a question that to every true hearted southerner is among the most difficult ever. Can the South be redeemed? (Rain FX and music up and udner). Chuck Reece (00:00:40): There's a giant fly in the ointment of Southern culture, and for centuries, white southerners have tried to deny it or Just ignore it, but it's deep in the source material of every little piece, every single artifact of our region's culture. And the fly I'm talking about of course, is slavery and the racial terror and oppression that followed it, and which sadly follow it still. Now I have to be open here, I'm a white guy. I'll be 60 years old, 11 months from now, but I've always known from the first minute I was exposed to it that racism is wrong. I was taught that all God's children were equal, and I was lucky enough to have a family that taught me that. But in general, why people in the South have been blind to the ways that we have benefited and continue to benefit from the violent lies of white supremacy. Chuck Reece (00:01:40): And for some of my listeners, especially people of color, you may need to bear with me in this episode because I'm waking up to my own need to name these things, to hear and see the full truth of them and to erase what white kids of my generation were taught and replace that with the truth. -

Chapter 5 – Open Space, Parks and Recreation

Chapter 5 Open Space, Parks and Recreation PERSONAL VISION STATEMENTS “An accessible city connected by green spaces.” “Well appointed parks with activities for all ages.” 5.1 CITY OF BIRMINGHAM COMPREHENSIVE PLAN PART II | CHAPTER 5 OPEN SPACE, PARKS AND RECREATION GOALS POLICIES FOR DECISION MAKERS Every resident is within a ten-minute • Assure, to the extent possible, that all communities are conveniently served by city walk of a park, greenway or other parks and recreational facilities. publicly accessible, usable open space. • Continue support for non-city parks that provide recreational amenities and access to nature. City parks and recreation facilities are • Provide recreational facilities and programs suited to the city’s changing population. safe, well-maintained and widely used. • Foster partnerships to improve and maintain park facilities. • Provide adequate, regular funding to maintain a high quality city parks and recreation system. The city’s major natural amenities are • Promote access and enjoyment of the city’s major water features and open spaces. enjoyed by residents and visitors. 5.2 CITY OF BIRMINGHAM COMPREHENSIVE PLAN PART II | CHAPTER 5 OPEN SPACE, PARKS AND RECREATION findings challenges Most residents are within a five to ten minute walk or City-owned parks are unevenly maintained. bicycle ride to a public park. City-owned parks are not consistently programmed City parks are maintained by the Public Works or equipped to maximize their use by neighborhood Department rather than the Parks and Recreation residents. Department. Declining neighborhood populations affect use and Private organizations have partnered with the City to programming in some city parks and recreation areas. -

Copyright by Celeste Evans Griffin 2010

Copyright by Celeste Evans Griffin 2010 The Professional Report Committee for Celeste Evans Griffin Certifies that this is the approved version of the following professional report: Arts-Based Adaptive Reuse Development in Birmingham, Alabama APPROVED BY SUPERVISING COMMITTEE: Supervisor: Bjorn Sletto Michael Oden Arts-Based Adaptive Reuse Development in Birmingham, Alabama by Celeste Evans Griffin, B.A.Psy. Professional Report Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of The University of Texas at Austin in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Science in Community and Regional Planning The University of Texas at Austin May 2010 Acknowledgements This report would not have been possible without the dedication of my primary advisor, Dr. Bjorn Sletto. His insight and guidance was invaluable throughout my research and writing process. I would also like to thank Dr. Michael Oden, my secondary advisor, who guided me in the economic and theoretical foundation of this report. Lastly, this report would not have come to fruition without my interviewees, Sara Cannon, David Fleming, Karen Cucinotta, Buddy Palmer, and Alan Hunter, who each provided critical insight into the assets, needs and potential of the arts community in Birmingham, Alabama. iv Abstract Arts-Based Adaptive Reuse Development in Birmingham, Alabama Celeste Evans Griffin, MSCRP The University of Texas at Austin, 2010 Supervisor: Bjorn Sletto This report, situated in Birmingham, Alabama, explores the best strategies for implementing arts-based adaptive reuse development in vacant or available downtown buildings. Through adaptive-reuse, a strategy of repurposing old buildings for new uses, the arts sector in Birmingham can be nurtured and strengthened. -

The Birmingham District Story

I THE BIRMINGHAM DISTRICT STORY: A STUDY OF ALTERNATIVES FOR AN INDUSTRIAL HERITAGE DISTRICT A Study Prepared for the National Park Service Department of the Interior under Cooperative Agreement CA-5000·1·9011 Birmingham Historical Society Birmingham, Alabama February 17, 1993 TABLE OF CONTENTS WHAT IS THE BIRMINGHAM HERITAGE DISTRICT? Tab 1 Preface National Park Service Project Summary The Heritage District Concept Vision, Mission, Objectives A COLLECTION OF SITES The Birmingham District Story - Words, Pictures & Maps Tab 2 Natural and Recreational Resources - A Summary & Maps Tab 3 Cultural Resources - A Summary, Lists & Maps Tab 4 Major Visitor Destinations & Development Opportunities A PARTNERSHIP OF COMMITTED INDIVIDUALS & ORGANIZATIONS Tabs Statements of Significance and Support Birmingham District Steering & Advisory Committees Birmingham District Research & Planning Team Financial Commitment to Industrial Heritage Preservation ALTERNATIVES FOR DISTRICT ORGANIZATION Tab 6 Issues for Organizing the District Alternatives for District Organization CONCLUSIONS, EARLY ACTION, COST ESTIMATES, SITE SPECIFIC Tab 7 DEVELOPMENTS, ECONOMIC IMPACT OF A HERITAGE DISTRICT APPENDICES Tab 8 Study Process, Background, and Public Participation Recent Developments in Heritage Area and Greenway Planning The Economic Impact of Heritage Tourism Visitor Center Site Selection Analysis Proposed Cultural Resource Studies Issues and Opportunities for Organizing the Birmingham Industrial Heritage District Index r 3 PREFACE This study is an unprecedented exploration of this metropolitan area founded on geology, organized along industrial transportation systems, developed with New South enthusiasm and layered with physical and cultural strata particular to time and place. It views as whole a sprawling territory usually described as fragmented. It traces historical sequence and connections only just beginning to be understood. -

019:091:AAA Media History & Culture

Media history and culture — p. 1 Summer 2013 019:091:AAA Media History & Culture 10:30A - 11:45A MTWTh 201 BCSB Prof. Frank Durham Office: E330 Adler Journalism Building (AJB) [email protected] ph. 335-3362 Office hours: Mon./Tues. 9-10:30 a.m. or by appointment The Journalism School office is located at room E305 in the Adler Journalism Building (AJB) ph. 335-3401 Course description To understand America’s past and its present, we must understand journalism and its role in the making of the nation. In this course, we will approach this learning project by addressing the broader social and political contexts within which American journalism has developed. Through a process of inquiry, we will learn about how journalists have defined conflicts between elites and workers, men and women, and how they have constructed definitions of racial and ethnic groups. In this way, this course and the text that Prof. Tom Oates and I have written for it, Defining the Mainstream: A Critical News Reader, addresses the origins, themes, and continuities of the press, both mainstream and minority. This perspective comes from examining exemplary (and, sometimes, exceptional) moments, as well as developing an understanding of more usual journalistic reactions and practices across time. In these discussions, I want to show you how and why journalism has played a part in defining social meaning in America. While the history of American journalism is rich with heroic stories about how journalists shaped and were shaped by events and trends, the content of the class about journalism will be new to almost all of you. -

Coming of Age in the Progressive South John T

Virginia Commonwealth University VCU Scholars Compass History Publications Dept. of History 1985 Coming of Age in the Progressive South John T. Kneebone Virginia Commonwealth University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarscompass.vcu.edu/hist_pubs Part of the Cultural History Commons, and the United States History Commons Copyright © 1985 by the University of North Carolina Press Recommended Citation Kneebone, John. "Coming of Age in the Progressive South." In Southern Liberal Journalists and the Issue of Race, 1920-1944. Chapel Hill: The nivU ersity of North Carolina Press, 1985, Available from VCU Scholars Compass, http://scholarscompass.vcu.edu/ hist_pubs/2. This Book Chapter is brought to you for free and open access by the Dept. of History at VCU Scholars Compass. It has been accepted for inclusion in History Publications by an authorized administrator of VCU Scholars Compass. For more information, please contact [email protected]. John t Kneebone Southern Liberal Journalists and the Issue of Race, 1920-1944 The University of North Carolina Press Chapel Hill & London ope" c.o l \ ~N 1,\<6'i:3 .KS£' Iqro~ © 1985 The University of North Carolina Press t,. '1- All rights reserved Manufactured in the United States of America Library of Congress Cataloging in Publication Data Kneebone, John T. Southern liberal journalists and the issue of race, 1920-1944. (Fred W. Morrison series in Southern studies) Bibliography: p. Includes index. 1. Race relations and the press-Southern States History-20th century. 2. Southern States-Race relations. 3. Liberalism-Southern States-History- 20th century. 1. Title. II. Series. PN4893.K58 1985 302.2'322'0975 85-1104 ISBN 0-8078-1660-4 1 Coming of Age in the Progressive South he South's leading liberal journalists came from various T backgrounds and lived in different regions of the South. -

Experience You Can Bank On

2332 Second Avenue North | Birmingham, AL 35203 | 205.458.9566 | HipBrandGroup.com Experience You Can Bank On. Brand Focused Marketers Whether you want to raise brand awareness, generate leads or drive revenue, you need a vibrant presence in today’s marketplace. HipBrand Group builds customized marketing programs for companies throughout the Southeast: We create brand positioning, advertising, digital tools, interactive campaigns and social business programs using the communications channels and creative strategies that work. We do this by tapping customer insights, tailoring the creative to each channel and employing the latest technology. The result is a seamless experience for users and full measurability for you. Unlike some boutique shops our experience is firmly grounded in solid, traditional marketing principles. From local, regional and national Addy awards, our team members have worked extensively for many of the South’s leading brands and companies over the last 25 years. We love what we do, and love getting it right. We find inspiration and success in working directly with accomplished people like you. We’ve learned a great deal more over the years and we’re pretty certain you can’t find a group as highly experi- enced and creatively talented anywhere. Especially not a team with such deep and integrated expertise in branding, digital marketing and public relations. Oh, and did we mention we’re humble, too? But don’t take our word for it. Peruse this agency overview and get to know us a bit through our bios and our work. Learn that we provide attentive service and strategic thinking. Then agree that together we’ll create results oriented communications that resonates deeply within each community you serve. -

Investigating Jewish Activism in Atlanta During the Civil Rights Movement

University of Pennsylvania ScholarlyCommons Undergraduate Humanities Forum 2014-2015: Penn Humanities Forum Undergraduate Color Research Fellows 5-2015 "The Implacable Surge of History": Investigating Jewish Activism in Atlanta During the Civil Rights Movement Danielle Rose Kerker University of Pennsylvania Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.upenn.edu/uhf_2015 Part of the Jewish Studies Commons, and the United States History Commons Kerker, Danielle Rose, ""The Implacable Surge of History": Investigating Jewish Activism in Atlanta During the Civil Rights Movement" (2015). Undergraduate Humanities Forum 2014-2015: Color. 5. https://repository.upenn.edu/uhf_2015/5 This paper was part of the 2014-2015 Penn Humanities Forum on Color. Find out more at http://www.phf.upenn.edu/annual-topics/color. This paper is posted at ScholarlyCommons. https://repository.upenn.edu/uhf_2015/5 For more information, please contact [email protected]. "The Implacable Surge of History": Investigating Jewish Activism in Atlanta During the Civil Rights Movement Abstract Existing works on southern Jewry illustrate how most southern Jews were concerned with self- preservation during the Civil Rights Movement. Many historians have untangled perceptions of southern Jewish detachment from civil rights issues to explain how individuals and communities were torn between their sympathy towards the African- American plight and Jewish vulnerability during a period of heightened racial tension. This project draws connections among the American Civil Rights Movement, the southern Jewish experience, and Atlanta race relations in order to identify instances of southern Jewish involvement in the fight for acialr equality. What were the forms of activism Jews chose, the circumstances that shaped those decisions, and the underlying goals behind them? Studying Atlanta’s Jewish communities during the 1950s and 1960s helps broaden the conversation on Jewish activism, raise questions of southern Jewish identity, and uncover distinctive avenues for change.