Reflections on Photography and the Visual Representation of Sport

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

World Rankings — Women’S 100H (Note: from ’56 Through ’68 the Ranked 1957 Distance Was 80 Meters) 1

World Rankings — Women’s 100H (note: from ’56 through ’68 the ranked 1957 distance was 80 meters) 1 ............ Nelli Yelisayeva (Soviet Union) 2 ..... Gisela Birkemeyer (East Germany) 3 ............Galina Bystrova (Soviet Union) 1956 4 .....Maria Golubnichaya (Soviet Union) 1 ............. Shirley de la Hunty (Australia) 5 .................Erika Fisch (West Germany) 2 ................ Zenta Kopp (West Germany) 6 ................ Zenta Kopp (West Germany) 3 ..... Gisela Birkemeyer (East Germany) 7 ...... Edeltraud Eiberle (West Germany) 4 ............Galina Bystrova (Soviet Union) 8 ..................... Gloria Wigney (Australia) 5 .....Maria Golubnichaya (Soviet Union) 9 .........................Betty Moore (Australia) 6 ...................Norma Thrower (Australia) 10 ...............................Elaine Winter (US) 7 .........Nina Vinogradova (Soviet Union) 8 .................Erika Fisch (West Germany) Keni Harrison didn’t make it to 9 ..................... Gloria Wigney (Australia) Rio, but was 2016’s No. 1 after 10 ........... Maria Sander (West Germany) her World Record. © VICTOR SAILER/PHOTO RUN © VICTOR SAILER/PHOTO RUN © Track & Field News 2020 — 1 — World Rankings — Women’s 100H 1958 1962 1 ............Galina Bystrova (Soviet Union) 1 .........................Betty Moore (Australia) 2 ................ Zenta Kopp (West Germany) 2 ............................Pam Ryan (Australia) 3 ..... Gisela Birkemeyer (East Germany) 3 ..........................Teresa Ciepła (Poland) 4 ...................Norma Thrower (Australia) 4 .................Erika -

JACQUELYN JOHNSON DOB: September 8, 1984 POB; San Jose, CA Ht: 5-8 Hometown: Yuma, AZ High School: Yuma HS, AZ College: Arizona State U ‘08

2008 Olympic Games Beijing Heptathlon Handbook and Media Guide DECA, The Decathlon Association Frank Zarnowski DECA, The Decathlon Association [email protected] Contents: Section 1: Schedule page 2 Section 2: The Field -History 2 -Qualifying standards 2 Section 3: The Likely Contenders…..bios Leading Contenders List 3 Ludmila Blonska 3 Anna Bogdonava 4 Tatyana Chernova 4 Hyleas Fountain 5 Jacqueline Johnson 5 Olga Kurban 6 Diana Pickler 6 Lilli Schwartzkopf 7 Austra Skujyte 7 Kelly Sotherton 8 Karolina Tyminska 8 Section 4: Record Section -Olympic Games medalists (1964-2004) 9 -Adenda 10 -Recent results (2000, 2004) 11 -Individual Event records 12 (World, American, OG,) Section 5: Pace -World, American and Olympic meet record pace 12 Section 6: USA team-expanded bios -Fountain, Hyleas 13 -Johnson, Jacqueline 14 -Pickler, Diana 15 1 Section 1: Schedule Friday Aug 15 Saturday Aug 16 100m Hurdles 9:00 Long Jump 9:50 High Jump 10:30 Javelin 19:00 Shot Put 19:00 800 m 21:45 200 m 21:15 Heptathlon medal ceremony: Section 2: The Field The field is likely to be the normal 30-33. In 1964 Tokyo 20 In 1968 Mexico City 33 In 1972 Munich 30 In 1976 Montreal 20 In 1980 Moscow In 1984 Los Angeles 23 In 1988 Seoul 30 in 1992 Barcelona 32 In 1996 Atlanta 29 In 2000 Sydney 33 In 2004 Athens 34 A standard = 6000 points (for 2 or 3 entries per nation) B standard = 5800 points (for a single entry by nation) [must be made between Sept. 1, 2006 and July 6, 2008; nb: Combined Events window was expanded this year]] 2 Section 3: The Likely Medal Contenders Leading contenders: qualifying mark PR notes Ludmila Blonska UKR 6832 (07) 6832 (07) ’07 WC 2nd, ’05 1st WiC Anna Bogdonava RUS 6452 (08) 6452 (08) 3rd WiC, 10th ’07 WC. -

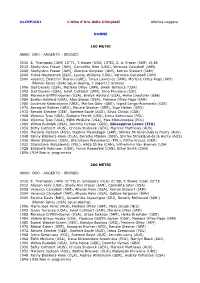

Argento - Bronzo

OLIMPIADI L'Albo d'Oro delle Olimpiadi Atletica Leggera DONNE 100 METRI ANNO ORO - ARGENTO - BRONZO 2016 E. Thompson (JAM) 10”71, T. Bowie (USA) 10”83, S. A. Fraser (JAM) 10,86 2012 Shelly-Ann Fraser (JAM), Carmelita Jeter (USA), Veronica Campbell (JAM) 2008 Shelly-Ann Fraser (JAM), Sherone Simpson (JAM), Kerron Stewart (JAM) 2004 Yuliva Nesterenko (BLR), Lauryn Williams (USA), Veronica Campbell (JAM) 2000 vacante, Ekaterini Thanou (GRE), Tanya Lawrence (JAM), Merlene Ottey-Page (JAM) (Marion Jones (USA) squal.doping, 2 argenti 1 bronzo) 1996 Gail Devers (USA), Merlene Ottey (JAM), Gwen Torrence (USA) 1992 Gail Devers (USA), Juliet Cuthbert (JAM), Irina Privalova (CSI) 1988 Florence Griffith-Joyner (USA), Evelyn Ashford (USA), Heike Drechsler (GEE) 1984 Evelyn Ashford (USA), Alice Brown (USA), Merlene Ottey-Page (JAM) 1980 Lyudmila Kondratyeva (URS), Marlies Göhr (GEE), Ingrid Lange-Auerswald (GEE) 1976 Annegret Richter (GEO), Renate Stecher (GEE), Inge Helten (GEO) 1972 Renate Stecher (GEE), Raelene Boyle (AUS), Silvia Chivás (CUB) 1968 Wyomia Tyus (USA), Barbara Ferrell (USA), Irena Szewinska (POL) 1964 Wyomia Tyus (USA), Edith McGuire (USA), Ewa Klobukowska (POL) 1960 Wilma Rudolph (USA), Dorothy Hyman (GBR), Giuseppina Leone (ITA) 1956 Betty Cuthbert (AUS), Christa Stubnick (GER), Marlene Matthews (AUS) 1952 Marjorie Jackson (AUS), Daphne Hasenjäger (SAF), Shirley Strickland-de la Hunty (AUS) 1948 Fanny Blankers-Koen (OLA), Dorothy Manley (GBR), Shirley Strickland-de la Hunty (AUS) 1936 Helen Stephens (USA), Stanislawa Walasiewicz (POL), Käthe Krauss (GER) 1932 Stanislawa Walasiewicz (POL), Hilda Strike (CAN), Wilhelmina Van Bremen (USA 1928 Elizabeth Robinson (USA), Fanny Rosenfeld (CAN), Ethel Smith (CAN) 1896-1924 Non in programma 200 METRI ANNO ORO - ARGENTO - BRONZO 2016 E. -

2011 European Indoor Championships Statistics – Women's

2011 European Indoor Championships Statistics – Women’s 60m (50m was contested in 1967-1969, 1972 and 1981) All time performance list at the European Indoor Championships Performance Performer Time Name Nat Pos Venue Year 1 1 7.00 Nelli Fiere -Cooman NED 1 Madrid 1986 2 7.01 Nelli Fiere -Cooman 1 Lievin 1987 3 7.02 Nelli Fiere -Cooman 1sf1 Lievin 1987 4 2 7.03 Anelia Nuneva BUL 2sf1 Lievin 1987 5 3 7.04 Silke Möller GDR 1sf1 Budapest 1988 6 7.04 Nelli Cooman 1 Budapest 1988 7 7.05 Silke Gladis ch Möller 2 Budapest 1988 8 4 7.05 Ekaterini Thanou GRE 1 Ghent 2000 9 7.06 Anelia Nuneva 2 Lievin 1987 10 7.07 Nelli Fiere -Cooman 1h1 Madrid 1986 11 5 7.07 Marlies Göhr GDR 1sf2 Lievin 1987 12 7.07 Marlies Göhr 3 Budapest 1988 13 7.08 Marlie s Göhr 2 Madrid 1986 14 7.09 Marlies Göhr 1 Budapest 1983 15 7.10 Nelli Fiere -Cooman 1 Pireas 1985 16 7.10 Nelli Fiere -Cooman 1sf2 Budapest 1988 17 6 7.10 Ulrike Sarvari FRG 1 Glasgow 1990 18 7 7.10 Kim Gevaert BEL 1sf2 Birmingham 2007 19 8 7.11 Sofka Popova BUL 1sf2 Sindelfingen 1980 20 7.11 Sofka Popova BUL 1 Sindelfingen 1980 21 7.11 Marlies Göhr 1 Milano 1982 22 7.11 Nelli Fiere -Cooman 1h3 Lievin 1987 23 9 7.11 Els Vader NED 2sf2 Lievin 1987 24 7.11 Silke Möller 1h3 Budapest 1988 25 10 7.11 Petya Pendareva BUL 2 Ghent 2000 26 11 7.11 Iryna Pukha UKR 3 Ghent 2000 27 7.12 Marlies Oelsner (Göhr) 1 Milano 1978 28 7.12 Silke Gladisch 2 Budapest 1983 29 7.12 Silke Gladisch 1h2 Madrid 1986 30 7.12 Marlies Göhr 3 Lievin 1987 31 7.12 Marlies Göhr 2sf2 Budapest 1988 32 7.12 Ekaterini Thanou 1sf1 Ghent 2000 33 -

World Rankings — Women's Heptathlon

World Rankings — Women’s Heptathlon © VICTOR SAILER/PHOTO RUN Carolina Klüft was No. 1 for 6 straight years, then unexpectedly became a long jumper in ’08, never tackling the multi again 6 different Pent/Hept versions 1956 1956–60: Day 1 was SP, HJ, 200 1 .........Nina Vinogradova (Soviet Union) Day 2 was 80H, LJ 2 .... Aleksandra Chudina (Soviet Union) 1961–68: Day 1 was 80H, SP, HJ 3 ................ Nilia Kulkova (Soviet Union) Day 2 was LJ, 200 4 ............Galina Bystrova (Soviet Union) 1969–76: Day 1 was 100H, SP, HJ 5 ......... Sofia Burdulenko (Soviet Union) Day 2 was LJ, 200 6 ............... Maria Sturm (West Germany) © VICTOR SAILER/PHOTO RUN 1977–80: Day 1 was 100H, SP, HJ 7 ........Klara Nikitinskaya (Soviet Union) Day 2 was LJ, 800 8 .....Galina Nozdracheva (Soviet Union) 1981–82: Day 1 was 100H, SP, HJ, 200 9 .......Yevgenia Gurevich (Soviet Union) Day 2 was LJ, JT, 800 10 .......... Galina Akimova (Soviet Union) 1983–present: Day 1 is 100H, HJ, SP, 200 Day 2 is LJ, JT, 800 © Track & Field News 2020 — 1 — World Rankings — Women’s Heptathlon 1957 1961 1 ............Galina Bystrova (Soviet Union) 1 .................... Irina Press (Soviet Union) 2 ............Lidia Shmakova (Soviet Union) 2 ............Galina Bystrova (Soviet Union) 3 ...... Edeltraud Eiberle (West Germany) 3 ... Tatyana Shchelkanova (Soviet Union) 4 .... Aleksandra Chudina (Soviet Union) 4 ............Lidia Shmakova (Soviet Union) 5 .............. Vilve Maremäe (Soviet Union) 5 ........... Maria Sizyakova (Soviet Union) 6 .......Zinaida Burenkova (Soviet Union) 6 ........ Helga Hoffmann (West Germany) 7 .........Nina Vinogradova (Soviet Union) 7 ................Olga Kardash (Soviet Union) 8 ........Christa Buchner (West Germany) 8 ............... -

NCAA Men Eligibles — Top 20 Returners

Table Of Contents From The Editor — Is The IAAF Being Innovative In The Right Places? ........................................................ 3 QUESTIONS FOR 2019 How Much Can Noah Lyles Add To His Legacy? ............................................................................................ 4 Are The Vultures Circling Kevin Young’s World Record? ................................................................................ 6 New Flag, New Beginning For Rai Benjamin ................................................................................................... 9 How Do You Qualify For The 2019 World Championships? .......................................................................... 12 Prediction Department — 2019 World Championships Medalists ............................................................... 14 How Will The 2019 Diamond League Work? ................................................................................................. 16 Major U.S. Names Coming Off The Shelf ...................................................................................................... 19 2019 COLLEGIATE PREVIEW NCAA Men Eligibles — Top 20 Returners ..................................................................................................... 23 Chris Nilsen To Face Crop Of Hot Frosh Vaulters ......................................................................................... 27 Shocked NCAA Steeple Champ Obsa Ali Ready For ’19 ............................................................................. -

2019 European Indoor Championships Statistics

2019 European Indoor Championships Statistics– Women’s 60mH by K Ken Nakamura All time performance list at the European Indoor Championships Performance Performer Time Name Nat Pos Venue Year 1 1 7.74 Lyudmila Narozhilenko URS 1 Glasgow 1990 2 2 7.75 Bettine Jahn GDR 1 Budapest 1983 3 3 7.77 Zofia Bielczyk POL 1 Sindelfingen 1980 3 3 7.77 Cornelia Oschkenat GDR 1 Budapest 1988 5 7.78 Lyudmila Narozhilenko 1sf1 Glasgow 1990 6 7.79 Cornelia Oschkenat 1 Madrid 1986 6 5 7.79 Yordanka Donkova BUL 1 Lievin 1987 8 6 7.80 Susanna Kallur SWE 1 Madrid 2005 8 6 7.80 Carolin Nytra GER 1 Paris 2011 8 6 7.80 Tiffany Porter GBR 2 Paris 2011 11 7.82 Lyudmila Narozhilenko 1 Genova 1992 11 7.82 Yordanka Donkova 1sf1 Lievin 1987 13 7.83 Cornelia Osc hkenat 1sf1 Budapest 1988 13 9 7.83 Christina Vukicevic NOR 3 Paris 2011 15 7.84 Cornelia Oschkenat 1sf1 Madrid 1986 15 10 7.84 Monique Ewanje -Epee FRA 2 Glasgow 1990 15 7.84 Susanna Kallur 1h1 Birmingham 2007 15 10 7.84 Alina Talay BLR 1 Praha 2015 19 12 7.85 Gloria Uibel GDR 1sf2 Lievin 1987 19 7.85 Yordanka Donkova 1 Paris 1994 19 12 7.85 Patricia Girard FRA 1 Valencia 1998 22 7.86 Zofia Bielczyk 1sf2 Sindelfingen 1980 22 14 7.86 Laurence Elloy FRA 1sf2 Madrid 1986 22 14 7.86 Mihae la Pogacian ROU 1sf2 Budapest 1988 22 14 7.86 Pamela Dutkiewicz GER 1h2 Beograd 2017 22 7.86 Alina Talay BLR 1sf1 Beograd 2017 27 7.87 Bettine Jahn 1h2 Budapest 1983 27 7.87 Yordanka Donkova 1 Den Haag 1989 27 7.87 Lyudmila Narozhilenko 1h1 Glasgow 1990 27 7.87 Susanna Kallur 1 Birmingham 2007 31 17 7.88 Linda Ferga FRA 1 Ghent -

From Monsters to “Women”: Sex, Science, Sport, and The

FROM MONSTERS TO “WOMEN”: SEX, SCIENCE, SPORT, AND THE STORY OF CASTER SEMENYA By © 2013 Jaclyn Howell Submitted to the graduate degree program in Communication Studies and the Graduate Faculty of the University of Kansas in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. _______________________________________ Dr. Dave Tell, Committee Chairperson _______________________________________ Dr. Robert Rowland ________________________________ Dr. Beth Innocenti ________________________________ Dr. Donn W. Parson ________________________________ Dr. Elizabeth MacGonagle Date Defended: November 15, 2013 ii The Dissertation Committee for Jaclyn Howell certifies that this is the approved version of the following dissertation: FROM MONSTERS TO “WOMEN”: SCIENCE, SEX, SPORT, AND THE STORY OF CASTER SEMENYA _______________________________________ Dr. Dave Tell, Committee Chairperson Date approved: November 15, 2013 iii Abstract My dissertation examines the various rhetorical techniques used to administrate gender and sex in the context of sport. Since the 1960s, the category of female has been treated as a prize to be won, reserved only for those who passed a variety of tests and who, quite literally, carried cards attesting to the authenticity of their sex. Given these restrictions on the category of the “female athlete,” I conclude that women in sport have always been a rhetorical creation. I use the controversy over South African runner Caster Semenya as an entry point to explore these techniques in their various forms from 1966 to the present day. In 2009, Semenya was subjected to a variety of gender tests – from stripping her of her clothes, swabbing her mouth for chromosomal analysis, or extracting blood samples for genetic analysis – each of which had a long history in sport, many of which had been officially banned, but all of which still influenced whether or not she counted as a female. -

Brexit Отрезви Испания Brexit Cooled Off Spain

WELCOME NOTE Dear Passengers, Welcome aboard Bulgaria Air! There’s something inexplicable in the way even people who are extremely uninterested in sport, start getting excited about the game with the Olympic medals. Янко Георгиев, Изпълнителен директор Yanko Georgiev, Executive Director It seems that even the opening ceremony Уважаеми пътници, of the Olympics – an endless string of strangely dressed athletes – touches a chord within our Добре дошли на борда на България Ер! soul and makes us frantically calculate whether or not we’ll be ahead of Kenya in the overall medal count. But before the Games in Rio de Има нещо необяснимо в начина, по който дори и крайно Janeiro begin and obsess your attention, allow незаинтересованите от спорта хора започват да се вълнуват от me to share some good news from the national играта с олимпийските медали. carrier. Starting June Bulgaria Air renews its direct flights to Budapest – come with us to explore Изглежда, още церемонията по откри- и неустоима жизненост. Или, ако пред- this remarkable city, combining imperial ването на олимпиадите – безкрайна вър- почитате плажовете и спокойствието, grandeur, elegance and irresistible energy. Or волица от странно облечени спортисти позволете да ви отведем до Лас Палмас и else, if you prefer beaches and peace, allow us - закача някаква тънка струна в душата Тенерифе. Или до която и да е от другите to take you to Las Palmas and Tenerife. Or any и ни кара трескаво да пресмятаме дали в ни дестинации. От вас се иска само едно: other of our destinations. You only need to do крайното класиране все пак ще изпреварим да изберете крайната си точка. -

Combined Track 1-15 2016.Indd

2016 TRACK & FIELD SCHEDULE IINDOORNDOOR SSEASONEASON Date Meet Location Jan. 16 at NAU Team Invitational Flagstaff , Ariz. Jan. 22-23 at Kansas State (Hep/Pent) Manhattan, Kan. Jan. 29-30 at Razorback Invitational Fayetteville, Ark. Feb. 05-06 at Frank Sevigne Husker Invitational Lincoln, Neb. Feb. 12-13 at Husky Classic Seattle, Wash. Feb. 26-27 at MPSF Championships Seattle, Wash. March 11-12 at NCAA Championships Birmingham, Ala. OOUTDOORUTDOOR SSEASONEASON Date Meet Location March 05 at Ben Brown Invitational Fullerton, Calif. March 22 Jim Bush Collegiate Invitational** Drake Stadium March 24 Legends of Track and Field Invitational ** Drake Stadium March 27-28 Rafer Johnson/Jackie Joyner-Kersee Invitational** Drake Stadium April 13-16 at Mt. Sac Relays Walnut, Calif. April 16 Texas A&M Drake Stadium April 22-23 at Triton Invitational San Diego, Calif. May 1 USC ** Drake Stadium May 7 at Oxy Distance Carnival Eagle Rock, Calif. May 7-8 at Pac-12 Multi-Event Championships Seattle, Wash. May 14-15 at Pac-12 Championships Seattle, Wash. May 26-28 at NCAA Preliminary Round Lawrence, Kan. June 8-11 at NCAA Championships Eugene, Ore. ** denotes UCLA home meet TABLE OF CONTENTS/QUICK FACTS QUICK FACTS TABLE OF CONTENTS Location .............................................................................J.D. Morgan Center, GENERAL INFORMATION ......................................325 Westwood Plaza, Los Angeles, Calif., 90095 2016 Schedule .........................Inside Front Cover Athletics Phone ......................................................................(310) -

JSP Vol 01 No 03 1962Nov

yvv' \0tJpMfc/fc NUMBER III NOVEMBER 1962 VOLUME I SEVENTH EUROPEAN ATHLETIC CHAMPIONSHIPS - Fred Farr - Only one new world record was established in the Seventh European Athletic Champion ships, held at Belgrade, Jugoslavia, from September 12th through the 16th. This new re cord was set by Gerarda Kraan of the Netherlands, whose first-place time in the women's 800 meter dash was 2:02.8, shattering the world record time of 2:04.3 set by L. Sevcova of the USSR in I960. In addition, Jutta Heine of Germany won first place in the wom en's 200 meters with a time of 23.5 seconds, which equals the new world record set by Dorothy Hyman of Great Britain on August fourth. Although the first place winners in most of these events exceeded the all-time rec ords for these Championships, it was conceded that even more spectacular results might have transpired if it were not for the intensive heat which plagued the athletes during these Championship games. Even worse, so far as the USSR team is concerned, was the withdrawal of Irina Press (hailed as the greatest all-round woman athlete) because of a strained muscle. To top it off, Tamara Press, sister of Irina, won first place in the shot put and discus throw — and then promptly announced that she was retiring, in order to study construction engineering! But all was not gloomy with the USSR team; they won 13 gold medals, 6 silver medals, and 10 bronze medals, thereby becoming the unofficial winners of these championship games. -

American Women and the Modern Summer Olympic Games: a Story of Obstacles and Struggles for Participation and Equality

UNIVERSITY OF MIAMI AMERICAN WOMEN AND THE MODERN SUMMER OLYMPIC GAMES: A STORY OF OBSTACLES AND STRUGGLES FOR PARTICIPATION AND EQUALITY By Cecile Houry A DISSERTATION Submitted to the Faculty of the University of Miami in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Coral Gables, Florida May 2011 ©2011 Cecile Houry All Rights Reserved UNIVERSITY OF MIAMI A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy AMERICAN WOMEN AND THE MODERN SUMMER OLYMPIC GAMES: A STORY OF OBSTACLES AND STRUGGLES FOR PARTICIPATION AND EQUALITY Cecile Houry Approved: ________________ _________________ Donald Spivey, Ph.D. Terri A. Scandura, Ph.D. Professor of History Dean of the Graduate School ________________ _________________ Robin Bachin, Ph.D. Gregory Bush, Ph.D. Professor of History Professor of History ________________ Andy Gillentine, Ph.D. Professor of Sport and Entertainment Management University of South Carolina HOURY, CECILE (Ph.D., History) American Women and the Modern Summer Olympic Games: (May 2011) A Story of Obstacles and Struggles for Participation and Equality Abstract of a dissertation at the University of Miami. Dissertation supervised by Professor Donald Spivey. No. of pages in text. (258) This dissertation focuses on American women and the modern summer Olympic Games. It retraces the history of women’s participation in this significant and global sporting event to study the obstacles generated by social, economic, political, and cultural gender patterns while providing a forum for female Olympians to give voice to their journeys and how they dealt with and eventually overcame some of these obstacles.