Arxiv:2007.05381V2 [Math.CO] 19 May 2021

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

![Arxiv:1712.08128V2 [Hep-Th] 27 Dec 2017 a Sophisticated Domain Wall-Type Defect, a Configuration of the D8 D8-Branes](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/5883/arxiv-1712-08128v2-hep-th-27-dec-2017-a-sophisticated-domain-wall-type-defect-a-con-guration-of-the-d8-d8-branes-185883.webp)

Arxiv:1712.08128V2 [Hep-Th] 27 Dec 2017 a Sophisticated Domain Wall-Type Defect, a Configuration of the D8 D8-Branes

Magnificent Four Nikita Nekrasov∗ Abstract We present a statistical mechanical model whose random variables are solid partitions, i.e. Young diagrams built by stacking up four dimensional hypercubes. Equivalently, it can be viewed as the model of random tessellations of R3 by squashed cubes of four fixed orientations. The model computes the refined index of a system of D0-branes in the presence of D8 D8 system, with a B-field strong enough to support the bound states. Mathematically,− it is the equivariant K-theoretic version of integration over the Hilbert scheme of points on C4 and its higher rank analogues, albeit the definition is real-, not complex analytic. The model is a mother of all random partition models, including the equivariant Donaldson-Thomas theory and the four dimensional instanton counting. Finally, a version of our model with infinite solid partitions with four fixed plane partition asymptotics is the vertex contribution to the equivariant count of instantons on toric Calabi-Yau fourfolds. The conjectured partition function of the model is presented. We have checked it up to six instantons (which is one step beyond the checks of the celebrated P. MacMahon’s failed conjectures of the early XX century). A specialization of the formula is our earlier (2004) conjecture on the equivariant K-theoretic Donaldson-Thomas theory, recently proven by A. Okounkov [68]. 1 Introduction This paper has several facets. From the mathematical point of view we are studying a com- binatorial problem. We assign a complex-valued probability to the collections of hypercubes in dimensions two to four, called the partitions, plane partitions, and solid partitions, respec- tively, and investigate the corresponding partition functions. -

A Proof of George Andrews' and Dave Robbins'q-TSPP Conjecture

A PROOF OF GEORGE ANDREWS’ AND DAVE ROBBINS’ A FÁÆÁÌE AÅÇÍÆÌ ÇF ÊÇÍÌÁÆE CAÄCÍÄAÌÁÇÆ˵ q-TSPP CONJECTURE ´ÅÇDÍÄÇ MANUEL KAUERS ∗, CHRISTOPH KOUTSCHAN ∗, AND DORON ZEILBERGER ∗∗ Accompanied by Maple packages TSPP and qTSPP available from http://www.math.rutgers.edu/~zeilberg/mamarim/mamarimhtml/qtspp.html. Pour Pierre Leroux, In Memoriam Preface: Montreal,´ May 1985 In the historic conference Combinatoire Enum´erative´ [6] wonderfully organized by Gilbert La- belle and Pierre Leroux there were many stimulating lectures, including a very interesting one by Pierre Leroux himself, who talked about his joint work with Xavier Viennot [7], on solving differential equations combinatorially! During the problem session of that very same colloque, chaired by Pierre Leroux, Richard Stanley raised some intriguing problems about the enumeration of plane partitions, that he later expanded into a fascinating article [9]. Most of these problems concerned the enumeration of symmetry classes of plane partitions, that were discussed in more detail in another article of Stanley [10]. All of the conjectures in the latter article have since been proved (see Dave Bressoud’s modern classic [2]), except one, that, so far, resisted the efforts of the greatest minds in enumerative combinatorics. It concerns the proof of an explicit formula for the q-enumeration of totally symmetric plane partitions, conjectured independently by George Andrews and Dave Robbins ([10], [9] (conj. 7), [2] (conj. 13)). In this tribute to Pierre Leroux, we describe how to prove that last stronghold. 1. q-TSPP: The Last Surviving Conjecture About Plane Partitions Recall that a plane partition π is an array π = (πij ), i, j 1, of positive integers πij with finite ≥ sum π = πij , which is weakly decreasing in rows and columns. -

Proof of George Andrews's and David Robbins's Q-TSPP Conjecture

Proof of George Andrews's and David Robbins's q-TSPP conjecture Christoph Koutschan ∗y, Manuel Kauers zx, Doron Zeilberger { ∗Department of Mathematics, Tulane University, New Orleans, LA 70118,zResearch Institute for Symbolic Computation, Johannes Kepler University Linz, A 4040 Linz, Austria, and {Mathematics Department, Rutgers University (New Brunswick), Piscataway, NJ 08854-8019 Edited by George E. Andrews, Pennsylvania State University, University Park, PA, and approved December 22, 2010 (received for review February 24, 2010) The conjecture that the orbit-counting generating function for to- tally symmetric plane partitions can be written as an explicit prod- uct formula, has been stated independently by George Andrews and David Robbins around 1983. We present a proof of this long- standing conjecture. computer algebra j enumerative combinatorics j partition theory 1 Proemium In the historical conference Combinatoire Enumerative´ that took place at the end of May 1985 in Montr´eal,Richard Stan- ley raised some intriguing problems about the enumeration of plane partitions (see below), which he later expanded into a fascinating article [11]. Most of these problems concerned the enumeration of \symmetry classes" of plane partitions that were discussed in more detail in another article of Stanley [12]. All of the conjectures in the latter article have since been proved (see David Bressoud's modern classic [3]), except one, which until now has resisted the efforts of some of the greatest minds in enumerative combinatorics. It concerns the proof of an explicit formula for the q-enumeration of totally symmet- ric plane partitions, conjectured around 1983 independently by George Andrews and David Robbins ([12], [11] conj. -

Plane Partitions Fermion-Boson Duality

Quantum crystals, Kagome lattice, and plane partitions fermion-boson duality Thiago Araujo,1, ∗ Domenico Orlando,1, 2, y and Susanne Reffert1, z 1Albert Einstein Center for Fundamental Physics, Institute for Theoretical Physics, University of Bern, Sidlerstrasse 5, ch-3012, Bern, Switzerland 2INFN, sezione di Torino and Arnold-Regge Center, via Pietro Giuria 1, 10125 Torino, Italy In this work we study quantum crystal melting in three space dimensions. Using an equivalent description in terms of dimers in a hexagonal lattice, we recast the crystal melting Hamiltonian as an occupancy problem in a Kagome lattice. The Hilbert space is spanned by states labeled by plane partitions, and writing them as a product of interlaced integer partitions, we define a fermion-boson duality for plane partitions. Finally, based upon the latter result we conjecture that the growth operators for the quantum Hamiltonian can be represented in terms of the affine Yangian Y[glb(1)]. I. INTRODUCTION addressed in [9]. Plane partitions can be written in terms of interlaced XXZ diagrams or as lattice fermions, see Random partitions appear in many contexts in mathe- figure (2). The empty partition is a configuration of the matics and physics. This omnipresence is partly explained hexagonal lattice where all positions below the diagonals by the fact that they are part of the core of number theory, are occupied. Additionally, based on the one- and two- the queen of mathematics [1]. It is nonetheless remarkable dimensional cases, a conjecture for the mass gap has been that they appear in a variety of distinct problems { such made, and further numerical analysis has been performed. -

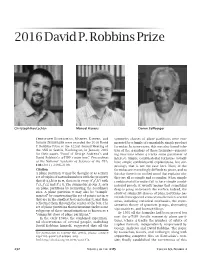

2016 David P. Robbins Prize

2016 David P. Robbins Prize Christoph Koutschan Manuel Kauers Doron Zeilberger Christoph Koutschan, Manuel Kauers, and symmetry classes of plane partitions were enu- Doron Zeilberger were awarded the 2016 David merated by a family of remarkably simple product P. Robbins Prize at the 122nd Annual Meeting of formulas. In some cases, this was also found to be the AMS in Seattle, Washington, in January 2016 true of the q-analogs of these formulas—generat- for their paper, “Proof of George Andrews’s and ing functions where q tracks some parameter of David Robbins’s q-TSPP conjecture,” Proceedings interest. Simple combinatorial formulas usually of the National Academy of Sciences of the USA, have simple combinatorial explanations, but sur- 108 (2011), 2196–2199. prisingly that is not the case here. Many of the Citation formulas are exceedingly difficult to prove, and to A plane partition π may be thought of as a finite this day there is no unified proof that explains why set of triples of natural numbers with the property they are all so simple and so similar. When simple that if (i, j,k) is in π, then so is every (i,j,k) with combinatorial formulas fail to have simple combi- i≤i, j≤j, and k≤ k. The symmetric group S 3 acts natorial proofs, it usually means that something on plane partitions by permuting the coordinate deep is going on beneath the surface. Indeed, the axes. A plane partition π may also be “comple- study of symmetry classes of plane partitions has mented” by constructing the set of points not in π revealed unexpected connections between several that are in the smallest box enclosing π, and then areas, including statistical mechanics, the repre- reflecting them through the center of the box. -

![Arxiv:1811.12857V2 [Math.AG] 5 Jun 2019 ..Teaction the 3.4](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/7318/arxiv-1811-12857v2-math-ag-5-jun-2019-teaction-the-3-4-1017318.webp)

Arxiv:1811.12857V2 [Math.AG] 5 Jun 2019 ..Teaction the 3.4

ENUMERATING COLOURED PARTITIONS IN 2 AND 3 DIMENSIONS BEN DAVISON, JARED ONGARO, AND BALAZS´ SZENDROI˝ Abstract. We study generating functions of ordinary and plane partitions coloured by the action of a finite subgroup of the corresponding special linear group. After reviewing known results for the case of ordinary partitions, we formulate a conjecture concerning a factorisation property of the generating function of coloured plane partitions that can be thought of as an orbifold analogue of a conjecture of Maulik et al., now a theorem, in three-dimensional Donaldson-Thomas theory. We study natural quantisations of the generating functions arising from geometry, discuss a quantised version of our conjecture, and prove a positivity result for the quantised coloured plane partition function under a geometric assumption. Contents 1. Introduction 2 2. Partitions 5 2.1. The abelian case: r-coloured partitions with diagonal colouring 5 2.2. Geometry and Lie theory 7 2.3. Partitions and Euler characteristics of Hilbert schemes 7 2.4. A nonabelian family of examples 9 2.5. Groups outside SL 11 3. Plane partitions: combinatorics 12 arXiv:1811.12857v2 [math.AG] 5 Jun 2019 3.1. The setup and the main conjecture 12 3.2. The action µr(1,r − 1, 0) and slr symmetry 13 ∼ 3 3.3. The case G = µ2 × µ2 and sl2-symmetry 14 3.4. The action µ3(1, 1, 1) and other cyclic cases 14 ∼ 3.5. The case G = µ3 × µ3 and the elusive e6-symmetry 15 4. Plane partitions: geometry 15 4.1. The geometry of the quotient and its resolutions 15 4.2. -

Arithmetic Properties of Plane Partitions

Arithmetic properties of plane partitions To Doron: a wonderful Mensch Tewodros Amdeberhan Victor H. Moll Department of Mathematics Department of Mathematics Tulane University, New Orleans, LA 70118 Tulane University, New Orleans, LA 70118 [email protected] [email protected] Submitted: Aug 31, 2010; Accepted: Oct 14, 2010; Published: Jan 2, 2011 Mathematics Subject Classification: 05A15, 11B75 Abstract The 2-adic valuations of sequences counting the number of alternating sign ma- trices of size n and the number of totally symmetric plane partitions are shown to be related in a simple manner. Keywords: valuations, alternating sign matrices, totally symmetric plane parti- tions. 1 Introduction A plane partition (PP) is an array π =(πij)i,j≥1 of nonnegative integers such that π has finite support and is weakly decreasing in rows and columns. These partitions are often represented by solid Young diagrams in 3-dimensions. MacMahon found a complicated formula for the enumeration of all PPs inside an n-cube. This was later simplified to n i + j + k − 1 PP = . (1) n Y i + j + k − 2 i,j,k=1 A plane partition is called symmetric (SPP) if πij = πji for all indices i, j. The number of such partitions whose solid Young diagrams fit inside an n-cube is given by n n n n i + j + n − 1 i + j + n − 1 SPP = = . (2) n Y Y i + j + i − 2 Y Y i + j − 1 j=1 i=1 j=1 i=j Another interesting subclass of partitions is that of totally symmetric plane partitions (TSPP). -

ON PLANE PARTITIONS and N–COLOR PARTITIONS Thesis

ON PLANE PARTITIONS AND n{COLOR PARTITIONS Thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirement for the award of the degree of Master of Science in Mathematics and Computing Submitted by Amrinder Kaur Roll no. 301503002 Under the guidance of Dr. Meenakshi Rana July 2017 School Of Mathematics Thapar University, Patiala INDIA Acknowledgements First of all, I would like to express my gratitude to Dr. Meenakshi Rana, Associate Professor, SOM, Thapar University, Patiala for their patient guid- ance and support throughout the work. I am truly very fortunate to work under her as a student. I would like to thank Dr. A.K. Lal, Associate Professor and Head, SOM, Thapar University, Patiala for providing help and all the necessary facilities in the department and directly or indirectly encouraging me to work harder during the whole work. I thank my parents for their lovely support. I admire my parent's determi- nation and sacrifice to get the best for me. July, 2017 Amrinder Kaur 2 Abstract The first chapter is devoted to preliminaries and provides introduction to plane partitions and n{color partitions. The second chapter elaborates the bijection between plane partitions and n{ color partitions through Bender and Knuth matrices using which some basic results are proved. The third chapter includes some theorems which give a nice interaction be- tween the plane partition and n{color partition. A relation between the rows of the plane partition and the subscripts of the n{color partition of any number ν is established in this chapter. Our results give a simpler way for finding the corresponding plane partition for a given n{color partition and vice{versa. -

Plane Partitions

PLANE PARTITIONS AMY BECKER, LILLY BETKE-BRUNSWICK, ANNA ZINK Abstract. Throughout our study of the enumeration of plane partitions we make use of bijective proofs to find generating functions. In particular, we con- sider bounded plane partitions, symmetric plane partitions and weak reverse plane partitions. Using the combinatorial interpretations of Schur functions in relation to semistandard Young tableaux, we rely on the properties of sym- metric functions. In our paper we will walk through some of these bijections and present the corresponding generating functions. 1. Introduction In order to understand and interpret plane partitions, it is important to have some background knowledge of various concepts. We will be reviewing the ba- sic ideas behind partitions, semistandard Young tableaux (SSYT), and symmetric functions{ specifically Schur functions{ to develop a strong base for the work we will be doing with plane partitions. We begin with the partition, the more com- monly seen 2-D version of a plane partition. Definition 1.1. For any nonnegative integer n, a partition λ of n is a nonin- 1 P1 creasing sequence fλjgj=1 of nonnegative integers such that j=1 λj = n. If λ is a partition of n then we often write jλj = n. We represent these partitions visually with what we call Ferrers diagrams. There are various styles of Ferrers diagrams, but we will be using the English version, which is left-aligned and stacked from top to bottom. λ1 λ2 λ3 Figure 1: Ferrers diagrams for a few partitions of n=5: λ1 = 4; 1, λ2 = 3; 2, and λ3 = 2; 2; 1. -

Enumeration of Integer Solutions to Linear Inequalities Defined by Digraphs3

Contemporary Mathematics Enumeration of Integer Solutions to Linear Inequalities Defined by Digraphs J. William Davis, Erwin D’Souza, Sunyoung Lee, and Carla D. Savage 1. Introduction This is the fourth in a series of papers [CS04, CSW05, CLS07] studying nonnegative integer solutions to linear inequalities as they relate to the enumer- ation of integer partitions and compositions. In this paper we consider solutions (λ1,...,λn) to a system C of inequalities in which every constraint is of the form λi ≥ λj (or λi >λj). In this case, C can be modeled by a directed graph (digraph) in which the vertices are labeled 1,...,n and there is an edge (or strict edge) from i to j if C contains the constraint λi ≥ λj (orλi >λj). Many familiar systems can be modeled in this way, including, ordinary partitions and compositions, plane partitions, monotone triangles, and plane partition diamonds and generalizations. Our focus is on the use of a particular set of tools to derive a recurrence for { | ≥ } the generating function FGn for an infinite family Gn n 1 of constraint sys- tems represented by digraphs. The recurrence can be viewed as a program which computes FGn for any given n. More significantly, if it can be solved, it provides a closed form for the generating function for the infinite family. The challenge becomes one of applying the tools strategically to get a recurrence for the graph Gn. Ultimately we want one where the associated recurrence for the generating function FGn can be solved. For the “digraph method” offered in this paper, we start with the five guidelines for partition analysis from [CLS07], reviewed in Section 2, and derive some special tools tailored to computing the generating function of a directed graph in Section 3. -

A Direct Bijection Between Descending Plane Partitions with No Special Parts and Permutation Matrices

CORE Metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk Provided by Elsevier - Publisher Connector Discrete Mathematics 311 (2011) 2581–2585 Contents lists available at SciVerse ScienceDirect Discrete Mathematics journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/disc Note A direct bijection between descending plane partitions with no special parts and permutation matrices Jessica Striker 1810 4th Ave S Minneapolis, MN 55404, United States article info a b s t r a c t Article history: We present a direct bijection between descending plane partitions with no special parts Received 12 January 2011 and permutation matrices. This bijection has the desirable property that the number Received in revised form 16 July 2011 of parts of the descending plane partition corresponds to the inversion number of the Accepted 22 July 2011 permutation. Additionally, the number of maximum parts in the descending plane partition Available online 17 August 2011 corresponds to the position of the one in the last column of the permutation matrix. We also discuss the possible extension of this approach to finding a bijection between descending Keywords: plane partitions and alternating sign matrices. Alternating sign matrix Descending plane partition ' 2011 Elsevier B.V. All rights reserved. Bijection 1. Introduction Alternating sign matrices have been objects of much inquiry over the past several decades with the most recent exciting development being the proof of the Razumov–Stroganov conjecture [4]. Descending plane partitions are objects equinumerous with alternating sign matrices, but there is no bijective proof known. In this paper, we find a direct bijection between these two sets of objects in the simplest special case. -

Proof of the Q-TSPP Conjecture

Proof of the q-TSPP Conjecture Christoph Koutschan (collaboration with Manuel Kauers and Doron Zeilberger) Research Institute for Symbolic Computation (RISC) Johannes Kepler Universit¨atLinz, Austria 13.09.2010 S´eminaireLotharingien de Combinatoire 65 TCSP CyclicallyTotally Symmetric Plane (3D Ferrers diagram) • two-dimensional array π = (πi;j)1≤i;j • πi;j 2 N with finite sum P jπj = πi;j • πi;j ≥ πi+1;j and πi;j ≥ πi;j+1 • πi;j = πj;i • cyclically symmetric 3D Ferrers diagram is invariant under the action of S3. P Partition 17 = 5+4+3+2+1+1+1 17 = 5+4+3+2+1+1+1 TCS CyclicallyTotally Symmetric (3D Ferrers diagram) • πi;j = πj;i • cyclically symmetric 3D Ferrers diagram is invariant under the action of S3. PP Plane Partition • two-dimensional array π = (πi;j)1≤i;j • πi;j 2 N with finite sum P jπj = πi;j • πi;j ≥ πi+1;j and πi;j ≥ πi;j+1 17 = 5+4+3+2+1+1+1 TCS CyclicallyTotally Symmetric • πi;j = πj;i • cyclically symmetric 3D Ferrers diagram is invariant under the action of S3. PP Plane Partition (3D Ferrers diagram) • two-dimensional array π = (πi;j)1≤i;j • πi;j 2 N with finite sum P jπj = πi;j • πi;j ≥ πi+1;j and πi;j ≥ πi;j+1 17 = 5+4+3+2+1+1+1 TC CyclicallyTotally (3D Ferrers diagram) • cyclically symmetric 3D Ferrers diagram is invariant under the action of S3. SPP Symmetric Plane Partition • two-dimensional array π = (πi;j)1≤i;j • πi;j 2 N with finite sum P jπj = πi;j • πi;j ≥ πi+1;j and πi;j ≥ πi;j+1 • πi;j = πj;i 17 = 5+4+3+2+1+1+1 T Totally (3D Ferrers diagram) • πi;j = πj;i 3D Ferrers diagram is invariant under the action of S3.