Encyclopedia of Japanese Business and Management

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

ISN - March, 1998 Newsletter

ISN - March, 1998 Newsletter http://neuroethology.org/newsletter/news_archive/isn.news.mar98.html Newsletter March 1998 International Society for Neuroethology c/o Panacea Associates phone/fax: +001 (850) 894-3480 744 Duparc Circle E-mail: [email protected] Tallahassee FL 32312 USA Website: www.neurobio.arizona.edu/isn/ LETTER FROM THE PRESIDENT With the arrival of a new year, an important transition began for the ISN. After many months of negotiations and planning, the ISN began a partnership with professional society managers, Panacea Associates (PA) of Tallahassee, Florida. PA is a small enterprise operated by Susan Lampman and Patricia Meredith, both of whom have had extensive experience in conference services, management of professional organizations, etc. PA has been managing the Association for Chemoreception Sciences (AChemS) for many years, and in that capacity they have earned a fine reputation for efficient and attentive service tailored to the needs of the organization. For a trial period of two years, most of the routine management operations of the ISN will be handled by PA. These services will be phased in over the next few months. For example, please notice that the membership form published in every issue of this Newsletter has changed. All completed membership forms, with payment as appropriate, should be mailed to the ISN at its new business address: International Society for Neuroethology, c/o Panacea Associates, 744 Duparc Circle, Tallahassee FL 32312, USA The ISN's new business phone/fax number is +001 (850) 894-3480, and its new business E-mail address is [email protected]. The URL of the ISN's Website will remain unchanged: www.neurobio.arizona.edu/isn/ I hope you have discovered by now that a searchable version of the ISN's Membership Directory is available at the Website. -

Learning Inamori Philosophy

Learning Inamori Philosophy Japan’s most influential social philosophy In comparison with Libertarianism and New Liberalism Iwao Taka Inamori Academy Kagoshima University 1-21-30 Korimoto Kagoshima 890-0065 Japan Copyright @ Iwao Taka 2020 First English version published 2020 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without the prior permission in writing of Iwao Taka or Inamori Academy, or as expressly permitted by law, by license or under terms agreed with the appropriate reprographics rights organization. Enquiries concerning reproduction outside the scope of above should be sent to Iwao Taka or Inamori Academy at the address above. CONTENTS How this book came about Preface What did Kazuo Inamori do? Two social philosophies that influence our thinking Dialogues with high school students Chapter 1 Utilitarianism as a Social Philosophy 1. Logical results of work 2. The issues discussed in social philosophy 3. Late Middle Ages and the beginning of philosophical explorations 4. Utilitarianism emerges 5. The pitfalls of utilitarianism Chapter 2 How Libertarianism Overcomes the Limitations of Utilitarianism 1. Libertarian explanations 2. The difference between laissez-faire economics and libertarianism 3. Libertarianism in a formula 4. Trade based on free will? 5. Result oriented society Chapter 3 Keynes’ Ideal Society 1. New Liberalism in a formula 2. Keynes’ basic questions 3. Flow of a nation’s economy 4. Multiplier effect of public projects 5. The propensity to consume and the economy 6. Problems in Japanese society 7. How financial transfer occurs Chapter 4 Rawls’ Ideal Society 1. -

The 12Th Pacific Rim Conference On

Hilton Waikoloa Village | Waikoloa, Hawaii, USA rld of Scie o nc Scan for meeting app. W e A CONFERENCE PROGRAM PACRIM a nd gy Technolo The 12th Pacific Rim Conference on Ceramic and Glass Technology including – Glass & Optical Materials Division Annual Meeting (GOMD 2017) May 21 – 26, 2017 PACRIM Partner Societies: The American Ceramic Society The Australian Ceramic Society The Ceramic Society of Japan The Chinese Ceramic Society ceramics.org/pacrim12 The Korean Ceramic Society Join Wiley and The American Ceramic Society at the 12th Pacific Rim Conference Including the Glass & Optical Materials Division Meeting JACerS Throughout 2017, we are celebrating the 100th anniversary of Celebrating the Journal of the American Ceramic Society. The most 100 Years of highly-respected global source for scholarly articles on ceramic Excellence materials research is enjoying its Centennial year and you can in 2017! JACerS: 1918–2017... learn all about it at wileyonlinelibrary.com/jacers100. and beyond This year at PACRIM/GOMD, take advantage of all these great offerings, plus more: • “So You Want to Get Published: A workshop for graduate students and young professionals” - led by Bill Fahrenholtz, Editor-in-Chief, Journal of the American Ceramic Society. - Monday, May 22, 2017, noon to 1:15 pm • Special Centennial Issue of JACerS available with unique articles and features picked by the editors • FREE sample copies of all 3 journals of the American Ceramic Society • Enjoy a 35% discount on all purchases at the Wiley booth • Meet with Wiley and ACerS -

Lecture Given by Dr. Kazuo Inamori, Director Emeritus of Ritsumeikan Inamori Philosophy Research Center

Lecture given by Dr. Kazuo Inamori, Director Emeritus of Ritsumeikan Inamori Philosophy Research Center The Significance of Rita no Kokoro for Business Administration (June 25, 2015 at Ritsumeikan University Osaka Ibaraki Campus) 1. Is Rita no Kokoro necessary for corporate management? Today, in commemoration of the opening of the Ritsumeikan Inamori Philosophy Research Center, I would like to speak about the significance of Rita no Kokoro for business administration and share with you the idea of rita, or “altruism,” which constitutes the very basis of my management philosophy. I am pleased to see so many people here today, including university researchers and business managers. Many of you may think that the idea of Rita no Kokoro, or “altruistic mind,” is simply ethical and moralistic, and it is irrelevant to corporate management. In fact, researchers and business managers often ask me, “While you stress the importance of ‘Rita no Kokoro’ for corporate management, isn’t it naive to maintain that we should be kind and considerate to others in doing business, given the nature of capitalist society in which companies are struggling to survive the intense market competition?” My answer to this frequently asked question is that for corporate managers, Rita no Kokoro is perfectly compatible with striving to improve corporate performance. As a corporate manager myself, I believe that acting for the benefit of others with the mindset of Rita no Kokoro and enhancing our moral sense is the key to successful corporate administration. I will discuss this belief in more detail in light of my experience at Kyocera, KDDI and Japan Airlines, respectively. -

No.60—2015 PURPOSE of PUBLICATION

ISSN : 0915-1478 CODEN : FFRDEK 60, 1-195 (2015) No.60—2015 PURPOSE OF PUBLICATION This annual publication is issued in order to introduce the results of research and development carried out in the laboratories of FUJIFILM Corporation and its subsidiaries. To provide an overview of our wide-ranging R&D activities across numerous business fields, this collection inc1udes the papers, which are new1y written or have already been published in various science and technology journals, regarding our noteworthy new products and novel technologies. In addition, a list of such papers published in journals and those presented at academic conferences in the past one year is attached at the end. © FUJIFILM Corporation 2015 Published by Strategic Corporate Technology Planning Division, Research & Development Management Headquarters, FUJIFILM Corporation Nakanuma, Minamiashigara, Kanagawa, 250-0193, Japan Kouichi Tamai Director and Executive Vice President Foreword FUJIFILM Corporation I served as Division Manager of FUJIFILM’s Medical Systems Business Division and Director of the Medical System Research & Development Center. In my role as Director of the R&D Center, I envisioned and developed products, which was an unusual job assignment. The double workload increased response speed and R&D productivity. In other words, I was obliged to quicken my pace. The current problems in our R&D activities are low yields of newly developed products and slow development speed. Some R&D personnel may disagree with this assessment for the following reasons: (i) they have confidence in their achievements and are unwilling to accept such a low opinion; (ii) they believe that yields of new products are naturally low; and (iii) they are indifferent or believe that developing new products is always difficult. -

January–June 2010

Topics January–June 2010 January 12— Tokyo International Airport (Haneda) opened world’s third highest new control tower (115.7 m) offshore from 2— Japan’s National Police Agency announced 2009 road new fourth runway (2500 m); “terminal radar control” accident fatalities dropped below 5000 mark for first time system, previously operated separately in Narita and in 57 years with decrease of 241 deaths over previous Haneda, centralized at Haneda year to 4914 and attributed to decrease in drunk driving 12— Fishing boat with 10 crew lost between Goto and Fukue and higher seatbelt usage islands, Nagasaki Prefecture, Japan with no sign of crew 2— Two train collisions in Uttar Pradesh, N. India caused 19— Financially troubled JAL applied for bankruptcy by dense fog and power cut killed 6 passengers and protection while restructuring business following losses injured 27 others of $23 billion—second largest ever loss for non-financial 3— Collapse of new bridge under construction at airport Japanese business; President Haruka Nishimatsu near Kunming, China, killed 7 workers and injured resigned and replaced as CEO by Kyocera Honorary 34 others President Kazuo Inamori from 1 February 4— EU announced plans to revise regulations governing 19— Korea’s Lotte Group announced business partnership introduction of full-body scanners for passengers at with Universal Studio Korea Resort (USKR) to build airports as anti-terror measure; since last year, airport film theme park in Hwaseong-shi, Gyeonggi-do near authorities in Holland, Nigeria, France, UK, Korea, etc., Seoul to open in March 2011 with studios, hotels, large decided on introduction, requiring revision of EU privacy shopping mall, apartments, golf course, etc. -

Silent AC Power Anywhere, Anytimesm

Silent AC Power Anywhere, AnytimeSM And we mean anywhere. Heart Interface offers an integrated system that includes an inverter/char- ger delivering reliable and dependable back-up power. Complete your electrical system with a Heart Interface Remote Control or LINK Battery Monitor that lets you know how much time you have left in your batteries. Call today or visit our website for a dealer near you. Heart Interface / 21440 68th Ave. S. / Kent, WA 98032 ® Tel: 253-872-7225 / FAX: 253-872-3412 www.heartinterface.com photo courtesy of ceder creek bed & breakfast. www.cedarcreektreehouse.com BP SOLAR BP Solar: we’re an advanced solar energy company. We manufacture premium solar modules and we’re on the leading edge with new, low cost technologies. But we do much more... We provide power solutions to enhance your quality of life and we have joined with industry leaders to bring you the best line of renewable energy products available, all backed by a name that is known and trusted throughout the world. USA: American Energy Technologies, Ltd. - Florida Effective Solar Products - Louisiana Intermountain Solar Technologies - Utah Toll Free: 800-874-2190 Toll Free: 888-824-0090 Toll Free: 800-671-0169 Phone: 904-284-0552 E-Mail: [email protected] Phone: 504-537-0090 Phone: 801-501-9353 E-mail: [email protected] E-mail: [email protected] Dankoff Solar Products - New Mexico Internet: www.effectivesolar.com Internet: www.intermountainsolar.com Toll Free: 888-396-6611 Phone: 505-473-3800 Alternative Solar Products - California Talmage Solar Engineering - Maine E-mail: [email protected] Toll Free: 800-229-7652 Toll Free: 888-967-5945 Alternative Energy Engineering - California Phone: 909-308-2366 Phone: 207-967-5945 Toll Free: 800-777-6609 E-mail: [email protected] E-mail: [email protected] Phone: 707-923-2277 Internet: www.alternativesolar.com Internet: www.talmagesolar.com E-mail: [email protected] Internet: www.alt-energy.com BP Solar, the world leader in solar electric systems, provides everything you need in a single package. -

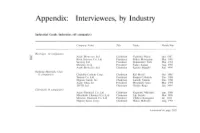

Appendix: Interviewees, by Industry

Appendix: Interviewees, by Industry Industrial Goods Industries (65 companies) Company Name Title Name Mo nth/Year Beverages (4 companies) to Asahi Breweries Ltd Chairman Tsutomu Murai Jun. 1987 Kirin Brewery Co. Ltd President Hideo Motoyama Mar. 1991 Suntory Ltd President Shininchiro Torii Mar. 1992 Mercian Corp. President Tadao Suzuki Aug. 1992 Asahi Breweries Ltd Chairman Kotaro Higuchi Sep. 1994 Building Materials, Glass (5 companies) Chichibu Cement Corp. Chairman Kei Moroi Oct. 1988 Tostem Co. Ltd President Kenjiro Ushioda Dec. 1988 Nippon Gaishi Inc. Chairman Junichi Takemi Dec. 1990 Asahi Glass Co. President Hiromichi Seya Mar. 1993 TOTO Ltd Chairman Yoshio Koga Jun. 1994 Chemicals (4 companies) Asahi Chemical Co. Ltd Chairman Kagayaki Miyazaki Apr. 1988 Mitsubishi Chemical Co. Ltd Chairman Eiji Suzuki May 1988 Shinetsu Chemical Co. Ltd President Chihiro Kanagawa Jul. 1993 Nippon Sanso Corp. Chairman Hideo Mabuchi Aug. 1993 (continued on page 292) Company Name Title Name Month/Year to Computer, Office Equipment (3 companies) IBM Japan Ltd President Takeo Shiina Jun. 1988 Fujitsu Ltd Chairman Takuma Yamamoto Feb. 1991 Nitsuko Corp. President Toshio Egashira Feb. 1995 Electronics, Electric Equipment (11 companies) Nippon Electric Co. Ltd Chairman Koji Kobayashi Jan. 1987 Mitsubushi Electric Corp Chairman Sadakazu Shinto Jul. 1987 FANAC Co. President Seiemon Inaba Oct. 87 Ushio Inc. Chairman Jiro Ushio Dec. 1988 Hitachi Ltd President Katsushige Mita Aug. 1989 Kyocera Corp. Chairman Kazuo Inamori Sep. 1989 OMRON Corp. President Yoshio Tateishi Oct. 1989 Matsushita Electric Industries President Akio Tanii Feb. 1992 Co. Ltd Matsushita Electric Works President Toshio Miyoshi Oct. 1993 Co. Ltd Nissin Electric Co. Ltd Chairman Shin Komatsu Feb. -

2 0 0 2 Annualreport

2002 ANNUAL REPORT SELECTED FINANCIAL DATA (in thousands, except per share data) Years Ended March 31, 1998 1999 2000 2001 2002 AVX 2002 Annual Report Income Statement Data: Net sales $1,267,653 $1,245,473 $1,630,273 $2,608,113 $1,249,980 Cost of sales 970,216 1,078,064 1,289,743 1,634,297 1,146,662 Gross profit 297,437 167,409 340,530 973,816 103,318 SG&A 110,737 114,104 119,299 149,268 103,741 Restructuring charges – – – – 24,646 Profit (loss) from operations 186,700 53,305 221,231 824,548 (25,069) Interest income 11,268 7,946 8,671 17,394 18,114 Interest expense (1,921) (2,228) (1,868) (2,320) (1,851) Other, net 1,377 1,719 4,092 1,638 1,800 Income (loss) before income taxes 197,424 60,742 232,126 841,260 (7,006) Provision for income taxes 62,773 19,226 75,194 273,723 226 Net income (loss) 134,651 41,516 156,932 567,537 (7,232) Income per share: Basic (1) $ 0.76 $ 0.24 $ 0.90 $ 3.25 $ (0.04) Diluted (1) $ 0.76 $ 0.24 $ 0.90 $ 3.22 $ (0.04) Cash dividends declared per common share (1) $ 0.123 $ 0.130 $ 0.135 $ 0.143 $ 0.150 As of March 31, 1998 1999 2000 2001 2002 Balance Sheet Data: Working capital $ 552,787 $ 471,253 $ 564,129 $1,011,753 $ 956,191 To tal assets 1,048,653 1,058,040 1,308,331 1,885,098 1,691,599 Long-term debt 8,376 12,714 18,174 13,722 – Stockholders’ equity 850,884 830,641 982,021 1,505,034 1,476,035 Years Ended March 31, 1998 1999 2000 2001 2002 Other Data: Capital expenditures 100,374 97,715 172,421 227,342 75,445 Research, development and engineering expenses 36,846 41,796 51,143 56,773 42,678 (1) Previously reported amounts have been restated for the effect of the June 1, 2000, 2-for-1 common stock split effected in the form of a 100% stock dividend. -

Kyocera Corporation by Chihiro Suematsu*

The Journal of Small Business Innovation 2018 20(4), pp. 33-38 Kyocera Corporation by Chihiro Suematsu* Kyocera Corporation is an electronic device, information equipment, and tele- communications equipment manufacturing company headquartered in Kyoto, Japan. The company’s success has depended on its differentiated technology in ceramic manu- facturing at the first stage. This technology was first sold to produce a part in TV CRT monitors, which boomed in the 1960s right after the company’s launch. Since its founding in 1959, the company has been continuously exploring technological, product, and business development backed by its strong entrepreneurial mindset. This mindset is nurtured by the “Kyocera philosophy,” the most important vision and motto of the company, which educates and encourages employees to grow themselves, respect others, and behave for all. This philosophy was advocated by the founder, Kazuo Inamori. Keywords : Kyocera Philosophy, Ameba Organization, Employee Independence, Free Will, Problem-Solving Skills, Creativity, Empathy, Thoughtfulness, Altruism * Kyoto University Graduate School of Management (e-mail: [email protected]) CHIHIRO SUEMATSU 33 Ⅰ. Business The company has expanded its global oper- Kyocera manufactures and sells electronic ations, including in Oceania, South America, devices, information equipment, and tele- South Africa, and Israel (Figure 2). communications equipment in the global The company continues to grow its rev- market (Figure 1). enue, with a CAGR of approximately 50% Company information for Kyocera is since its founding (Figure 3). It also continues shown below: to diversify its product lines, from ceramic - Revenue: \1,423 billion parts to information and telecommunications - Capital: \115 billion equipment, to various products that include - Employees: 70,000 photocopiers, cameras, VCRs, smartphones, Figure 1 Kyocer’s Products Source: http://global.kyocera.com/company/summary/company_profile.html. -

Disruptive Philosophy: a Turnaround Artist with Heart

The International Journal of Ethical Leadership Volume 3 Article 6 2015 Disruptive Philosophy: A Turnaround Artist with Heart Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarlycommons.law.case.edu/ijel Part of the Applied Ethics Commons, Business Law, Public Responsibility, and Ethics Commons, Leadership Studies Commons, and the Legal Ethics and Professional Responsibility Commons Recommended Citation (2015) "Disruptive Philosophy: A Turnaround Artist with Heart," The International Journal of Ethical Leadership: Vol. 3 , Article 6. Available at: https://scholarlycommons.law.case.edu/ijel/vol3/iss1/6 This Case Study is brought to you for free and open access by the Cross Disciplinary Publications at Case Western Reserve University School of Law Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in The International Journal of Ethical Leadership by an authorized administrator of Case Western Reserve University School of Law Scholarly Commons. et al.: Disruptive Philosophy: A Turnaround Artist with Heart Case Study Disruptive Philosophy: A Turnaround Artist with a Heart Shannon E. French French, Bilimoria, & Boyatzis Inamori Professor of Ethics, Director, Inamori International Center for Ethics and Excellence, Case Western Reserve University; Diana Bilimoria Chair, Department of Organizational Behavior, KeyBank Professor, Case Western Reserve University; and Richard E. Boyatzis, Distinguished University Professor, H.R. Horvitz Professor of Family Business, Case Western Reserve University As Ishiro Tanaka1 left the train and walked to the hanger, he felt something odd. He was not excited to spend time with his engines. Yes, he felt the jet engines on which he worked were “his” engines. He loved to hear them sing a song as they hummed. -

CSR Report 2018 (Pdf/7273KB)

2018 Contents Management Rationale / Top Management Message 002 Corporate Motto / Management Rationale 003 Top Management Message Management Philosophy 005 Kyocera Group Management Roots 007 Management Based on the Kyocera Philosophy 008 Advancing Kyocera Philosophy Education Management 012 Kyocera Group Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) 025 Corporate Governance Respect for Human Rights / Optimal Work Environment 029 Promotion of Diversity and Inclusion 035 Cultivation of Human Resources 039 Building a Safe & Secure Work Environment Environmental Activities 044 Kyocera Group Environmental Basic Philosophy and Policy 050 Green Management 054 Green Products 066 Green Factories 077 Green Communication Fair Business Activities 081 Risk Management and Compliance 090 Supply Chain Management Customer Concerns 093 Approaches to Raising Quality and Customer Satisfaction Levels Social Contribution Activities 096 Academic Advancement and Research 099 Support for Culture and the Arts 100 International Exchange and Collaboration 104 Local Community Activities 108 Editorial Policy 109 GRI and ISO26000 Comparison Tables 1 Management Rationale / Top Management Message Corporate Motto / Management Rationale Corporate Motto “Respect the Divine and Love People” Management Rationale To provide opportunities for the material and intellectual growth of all our employees, and through our joint efforts, contribute to the advancement of society and humankind. Management Philosophy To coexist harmoniously with our society, our global community and nature. Harmonious coexistence is the underlying foundation of all our business activities as we work to create a world of prosperity and peace. Methods of Management 1. To earn fair profit through harmonious business practices that result in products that satisfy our customers — providing quality products at lower prices, realized through ongoing R&D and sincere service.