Internships, Workfare, and the Cultural Industries: a British Perspective

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Hilary Mantel Papers

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/c8gm8d1h No online items Hilary Mantel Papers Finding aid prepared by Natalie Russell, October 12, 2007 and Gayle Richardson, January 10, 2018. The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens Manuscripts Department 1151 Oxford Road San Marino, California 91108 Phone: (626) 405-2191 Email: [email protected] URL: http://www.huntington.org © October 2007 The Huntington Library. All rights reserved. Hilary Mantel Papers mssMN 1-3264 1 Overview of the Collection Title: Hilary Mantel Papers Dates (inclusive): 1980-2016 Collection Number: mssMN 1-3264 Creator: Mantel, Hilary, 1952-. Extent: 11,305 pieces; 132 boxes. Repository: The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens. Manuscripts Department 1151 Oxford Road San Marino, California 91108 Phone: (626) 405-2191 Email: [email protected] URL: http://www.huntington.org Abstract: The collection is comprised primarily of the manuscripts and correspondence of British novelist Hilary Mantel (1952-). Manuscripts include short stories, lectures, interviews, scripts, radio plays, articles and reviews, as well as various drafts and notes for Mantel's novels; also included: photographs, audio materials and ephemera. Language: English. Access Hilary Mantel’s diaries are sealed for her lifetime. The collection is open to qualified researchers by prior application through the Reader Services Department. For more information, contact Reader Services. Publication Rights The Huntington Library does not require that researchers request permission to quote from or publish images of this material, nor does it charge fees for such activities. The responsibility for identifying the copyright holder, if there is one, and obtaining necessary permissions rests with the researcher. -

Fall 2019 Catalog (PDF)

19F Macm Farrar, Straus and Giroux The Topeka School A Novel by Ben Lerner From the award-winning author of 10:04 and Leaving the Atocha Station, a tender and expansive family drama set in the American Midwest at the turn of the century: a tale of adolescence, transgression, and the conditions that have given rise to the trolls and tyrants of the new right Adam Gordon is a senior at Topeka High School, class of 1997. His mother, Jane, is a famous feminist author; his father, Jonathan, is an expert at getting lost boys" to open up. They both work at the Foundation, a well-known psychiatric clinic that has attracted staff and patients from around the world. Adam is a renowned debater and orator, expected to win a national championship before he heads to college. He is an aspiring poet. He is - although it requires a great deal of posturing, weight lifting, and creatine supplements - one of the cool kids, passing himself off as a "real man," ready to fight or (better) freestyle about fighting if it keeps his peers from thinking of him as weak. Adam is also one of the seniors who brings the loner Darren Farrar, Straus and Giroux Eberheart - who is, unbeknownst to Adam, his father's patient - into the social On Sale: Oct 1/19 scene, with disastrous effects. 6 x 9 • 304 pages Deftly shifting perspectives and time periods, Ben Lerner's The Topeka 1 Black-and-White Illustration School is the story of a family's struggles and strengths: Jane's reckoning with 9780374277789 • $34.00 • CL - With dust jacket the legacy of an abusive father, Jonathan's marital transgressions, the Fiction / Literary challenge of raising a good son in a culture of toxic masculinity. -

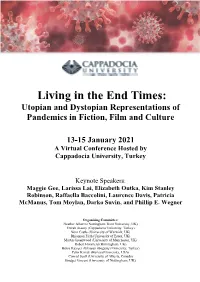

Living in the End Times Programme

Living in the End Times: Utopian and Dystopian Representations of Pandemics in Fiction, Film and Culture 13-15 January 2021 A Virtual Conference Hosted by Cappadocia University, Turkey Keynote Speakers: Maggie Gee, Larissa Lai, Elizabeth Outka, Kim Stanley Robinson, Raffaella Baccolini, Laurence Davis, Patricia McManus, Tom Moylan, Darko Suvin, and Phillip E. Wegner Organising Committee: Heather Alberro (Nottingham Trent University, UK) Emrah Atasoy (Cappadocia University, Turkey) Nora Castle (University of Warwick, UK) Rhiannon Firth (University of Essex, UK) Martin Greenwood (University of Manchester, UK) Robert Horsfield (Birmingham, UK) Burcu Kayışcı Akkoyun (Boğaziçi University, Turkey) Pelin Kıvrak (Harvard University, USA) Conrad Scott (University of Alberta, Canada) Bridget Vincent (University of Nottingham, UK) Contents Conference Schedule 01 Time Zone Cheat Sheets 07 Schedule Overview & Teams/Zoom Links 09 Keynote Speaker Bios 13 Musician Bios 18 Organising Committee 19 Panel Abstracts Day 2 - January 14 Session 1 23 Session 2 35 Session 3 47 Session 4 61 Day 3 - January 15 Session 1 75 Session 2 89 Session 3 103 Session 4 119 Presenter Bios 134 Acknowledgements 176 For continuing updates, visit our conference website: https://tinyurl.com/PandemicImaginaries Conference Schedule Turkish Day 1 - January 13 Time Opening Ceremony 16:00- Welcoming Remarks by Cappadocia University and 17:30 Conference Organizing Committee 17:30- Coffee Break (30 min) 18:00 Keynote Address 1 ‘End Times, New Visions: 18:00- The Literary Aftermath of the Influenza Pandemic’ 19:30 Elizabeth Outka Chair: Sinan Akıllı Meal Break (60 min) & Concert (19:45-20:15) 19:30- Natali Boghossian, mezzo-soprano 20:30 Hans van Beelen, piano Keynote Address 2 20:30- 22:00 Kim Stanley Robinson Chair: Tom Moylan Follow us on Twitter @PImaginaries, and don’t forget to use our conference hashtag #PandemicImaginaries. -

United Kingdom

FREEDOM ON THE NET 2014 United Kingdom 2013 2014 Population: 64.1 million Internet Freedom Status Free Free Internet Penetration 2013: 90 percent Social Media/ICT Apps Blocked: No Obstacles to Access (0-25) 2 2 Political/Social Content Blocked: No Limits on Content (0-35) 6 6 Bloggers/ICT Users Arrested: No Violations of User Rights (0-40) 15 16 TOTAL* (0-100) 23 24 Press Freedom 2014 Status: Free * 0=most free, 100=least free Key Developments: May 2013 – May 2014 • Filtering mechanisms, particularly child-protection filters enabled on all household and mobile connections by default, inadvertently blocked legitimate online content (see Limits on Content). • The Defamation Act, which came into effect on 1 January 2014, introduced greater legal protections for intermediaries and reduced the scope for “libel tourism,” while proposed amendments to the Contempt of Court Act may introduce similar protections for intermediaries in relation to contempt of court (see Limits on Content and Violations of User Rights). • New guidelines published by the Director of Public Prosecutions in June 2013 sought to limit offenses for which social media users may face criminal charges. Users faced civil penalties for libel cases, while at least two individuals were imprisoned for violent threats made on Facebook and Twitter (see Violations of User Rights). • In April 2014, the European Court of Justice determined that EU rules on the mass retention of user data by ISPs violated fundamental privacy and data protection rights. UK privacy groups criticized parliament for rushing through “emergency” legislation to maintain the practice in July, while failing to hold a public debate on the wider issue of surveillance (see Violations of User Rights). -

Iain Sinclair's Olympics

Iain Sinclair’s Olympics volume 34 number 16 30 august 2012 £3.50 us & canada $4.95 David Trotter: Lady Chatterley’s Sneakers Karl Miller: Stephen Spender’s Stories Stefan Collini: Eliot and the Dons Bruce Whitehouse: Mali Breaks Down Sheila Heti: ‘Leaving the Atocha Station’ London Review of Books volume 34 number 16 30 august 2012 £3.50 us and canada $4.95 3 David Trotter Lady Chatterley’s Sneakers editor: Mary-Kay Wilmers deputy editor: Jean McNicol senior editors: Christian Lorentzen, 4 Letters Karuna Mantena, Rosinka Chaudhuri, Amit Pandya, Ananya Vajpeyi, Paul Myerscough, Daniel Soar assistant editors: Andrew Whitehead, Miles Larmer, Marina Warner, A.E.J. Fitchett, Joanna Biggs, Deborah Friedell Stan Persky editorial assistant: Nick Richardson editorial intern: Alice Spawls contributing editors: Jenny Diski, 8 Steven Shapin World in the Balance: The Historic Quest for an Absolute System of Measurement Jeremy Harding, Rosemary Hill, Thomas Jones, by Robert Crease John Lanchester, James Meek, Andrew O’Hagan, Adam Shatz, Christopher Tayler, Colm Tóibín consulting editor: John Sturrock 11 Karl Miller New Selected Journals, 1939-95 by Stephen Spender, edited by Lara Feigel and publisher: Nicholas Spice John Sutherland associate publishers: Margot Broderick, Helen Jeffrey advertising director: Tim Johnson 12 Bill Manhire Poems: ‘Old Man Puzzled by His New Pyjamas’, ‘The Question Poem’ advertising executive: Siddhartha Lokanandi advertising manager: Kate Parkinson classifieds executive: Natasha Chahal 13 Stefan Collini The Letters of T.S. -

John Lanchester Writer - Fiction/Children's

John Lanchester Writer - fiction/children's John Lanchester was born in Hamburg in 1962. He was brought up in the Far East and educated in England. He has worked as an editor at Penguin, was Deputy Editor of the London Review of Books (and remains on its editorial board), and has also written a weekly column for the Daily Telegraph. His first novel, THE DEBT TO PLEASURE, published by Picador in 1996, won the Whitbread First Novel Award, the Betty Trask Prize and the Hawthornden Prize. His second novel, MR PHILLIPS (Faber), was published in 2000 and was hailed as a “postmodern Ulysses”. Agents Caradoc King Agent Millie Hoskins [email protected] Assistant Becky Percival [email protected] 020 3214 0932 Publications Fiction Publication Notes Details REALITY AND Household gizmos with a mind of their own. Constant cold calls from unknown OTHER numbers. And the creeping suspicion that none of this is real. Reality, and Other STORIES Stories is a gathering of deliciously chilling entertainments - stories to be read as 2020 the evenings draw in and the days are haunted by all the ghastly schlock, uncanny UK: Faber US: technologies and absurd horrors of modern life. Norton United Agents | 12-26 Lexington Street London W1F OLE | T +44 (0) 20 3214 0800 | F +44 (0) 20 3214 0801 | E [email protected] Publication Notes Details THE WALL Kavanagh begins his life patrolling the Wall. If he's lucky, if nothing goes wrong, he 2019 only has two years of this, 729 more nights. The best thing that can happen is that Faber & Faber he survives and gets off the Wall and never has to spend another day of his life anywhere near it. -

Witness Statement of Eric King

IN THE INVESTIGATORY POWERS TRIBUNAL Case No IPT/13/92/CH BETWEEN: PRIVACY INTERNATIONAL Claimants -and- (1) SECRETARY OF STATE FOR FOREIGN AND COMMONWEALTH AFFAIRS (2) GOVERNMENT COMMUNICATION HEADQUARTERS Defendants WITNESS STATEMENT OF ERIC KING I, Eric King, Deputy Director, Privacy International, 62 Britton Street, London EC1M 5UY, SAY AS FOLLOWS: 1. I am the Deputy Director of Privacy International. 2. I hold a Bachelor of Laws from the London School of Economics and have worked on issues related to communications surveillance at Privacy International since 2011. My areas of interest and expertise are signals intelligence, surveillance technologies and communications surveillance practices. I regularly speak at academic conferences, with government policy makers, and to international media. I have spent the past year researching the “Five Eyes” intelligence-sharing arrangement and the materials disclosed by Edward Snowden. 3. I make this statement in support of Privacy International’s claim. The contents of this statement are true to the best of my knowledge, information and belief and are the product of discussion and consultation with other experts. Where I rely on other sources, I have endeavoured to identify the source . 4. In this statement I will address, in turn, the following matters: a. The transmission and interception of digital communications; b. The difference between internal and external communications under RIPA, as applied to the internet and modern communications techniques; c. Intelligence sharing practices among the US, UK, Australia, New Zealand and Canada (“the Five Eyes”); d. The UK’s consequent access to signals intelligence collected by the United States through its PRISM and UPSTREAM collection programmes; e. -

Drpjournal 5Pm S1 2011.Pdf

table of contents table of contents Digital Publishing: what we gain and what we lose 4 The Impact of Convergence Culture on News Publishing: the Shutong Wang rise of the Blogger 112 Renae Englert Making Online Pay: the prospect of the paywall in a digital and networked economy 14 The New Design of Digital Contents for Government Yi Wang Applications: new generations of citizens and smart phones applications 120 E-mail Spam: advantages and impacts in digital publishing 22 Lorena Hevia Haoyu Qian Solving the Digital Divide: how the National Broadband Net- Advertising in the new media age 32 work will impact inequality of online access in Australia Quan Quan Chen 133 Michael Roberts Twitter Theatre: notes on theatre texts and social media platforms 40 The Blurring of Roles: journalists and citizens in the new Alejandra Montemayor Loyo media landscape Nikki Bradley 145 The appearance and impacts of electronic magazines from the perspective of media production and consumption 50 Wikileaks and its Spinoffs:new models of journalism or the new Ting Xu media gatekeepers? 157 Nadeemy Chen Pirates Versus Ninjas: the implications of hacker culture for eBook publishing 60 Shannon Glass Online Library and Copyright Protection 73 Yang Guo Identities Collide: blogging blurs boundaries 81 Jessica Graham How to Use Sina Microblog for Brand Marketing 90 Jingjing Yu Inheriting the First Amendment: a comparative framing analysis of the opposition to online content regulation 99 Sebastian Dixon journal of digital research + publishing - 2011 2 journal of digital research + publishing - 2011 3 considerably, reaching nearly 23% of the level of printed book Digital Publishing: what we gain and usage. -

Edward Snowden - Wikipedia, the Free Encyclopedia

Edward Snowden - Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Edward_Snowden Edward Snowden From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia Further information: Global surveillance disclosures (2013–present) Edward Snowden Edward Joseph Snowden (born June 21, 1983) is an American computer specialist, a former Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) employee, and former National Security Agency (NSA) contractor who disclosed top secret NSA documents to several media outlets, initiating the NSA leaks, which reveal operational details of a global surveillance apparatus run by the NSA and other members of the Five Eyes alliance, along with numerous commercial and international partners.[3] The release of classified material was called the most significant leak in US history by Pentagon Papers leaker Daniel Ellsberg. A series of exposés beginning Screen capture from the interview with Glenn June 5, 2013 revealed Internet surveillance programs Greenwald and Laura Poitras on June 6, 2013 such as PRISM, XKeyscore and Tempora, as well as the interception of US and European telephone Born Edward Joseph Snowden metadata. The reports were based on documents June 21, 1983 Snowden leaked to The Guardian and The Elizabeth City, North Carolina, Washington Post while employed by NSA contractor United States Booz Allen Hamilton. By November 2013, The Residence Russia (temporary asylum) Guardian had published one percent of the documents, with "the worst yet to come". Nationality American Occupation System administrator Snowden flew to Hong Kong from his home in Employer Booz Allen Hamilton[1] Hawaii on May 20, 2013, where he later met with journalists Glenn Greenwald and Laura Poitras and Kunia, Hawaii, US (until June 10, 2013) released his copies of the NSA documents.[4][5] After disclosing his identity, he fled Hong Kong and landed Known for Revealing details of classified United at Moscow's Sheremetyevo International Airport on States government surveillance June 23, reportedly for a one-night layover en route to programs Ecuador. -

The Mothers Genevieve Gannon

AUSTRALIA JANUARY 2020 The Mothers Genevieve Gannon What if you gave birth to someone else's child? A gripping family drama inspired by a real-life case of an IVF laboratory mix-up. Description 'Engagingly and unflinchingly told, Gannon's new novel, The Mothers, is the story of every parent's worst nightmare. It is that novel that makes you muse on the most difficult of questions ... What makes a mother? And can you ever un-become one? Like all my favourite books, The Mothers is both heartbreaking and heartwarming, and it leaves you with a lot to think about after you turn the final page. I sobbed my way through this wonderful book.' - Sally Hepworth, bestselling author of The Mother-in-Law Two couples. One baby. An unimaginable choice. Grace and Dan Arden are in their forties and have been on the IVF treadmill since the day they got married. Six attempts have yielded no results and with each failure a little piece of their hope dies. Indian-Australian Priya Laghari and her husband Nick Archer are being treated at the same fertility clinic and while the younger couple doesn't face the same time pressure as the Ardens, the Archers have their own problems. Priya suspects Nick is cheating and when she discovers a dating app on his phone her worst fears are confirmed.? Priya leaves Nick and goes through an IVF cycle with donor sperm. On the day of her appointment, Grace and Dan also go in for their final, last-chance embryo transfer. Two weeks later the women both get their results: Grace is pregnant. -

John Lanchester, 'You Are the Product'

05/06/2020 John Lanchester · You Are the Product: It Zucks! · LRB 16 August 2017 Vol. 39 No. 16 · 17 August 2017 You Are the Product John Lanchester T A M: F D N S M, H O T A I H S by Tim Wu (/search-results?search=Tim Wu) . Atlantic, 416 pp., £20, January 2017, 978 1 78239 482 2 C M: I S V M M by Antonio García Martínez (/search-results?search=Antonio García Martínez) . Ebury, 528 pp., £8.99, June 2017, 978 1 78503 455 8 M F B T: H F, G A C C W I M A U by Jonathan Taplin (/search-results?search=Jonathan Taplin) . Macmillan, 320 pp., £18.99, May 2017, 978 1 5098 4769 3 of June, Mark Zuckerberg announced that Facebook had hit a new level: two billion monthly active users. That number, the company’s preferred ‘metric’ when A measuring its own size, means two billion dierent people used Facebook in the preceding month. It is hard to grasp just how extraordinary that is. Bear in mind that thefacebook – its original name – was launched exclusively for Harvard students in 2004. No human enterprise, no new technology or utility or service, has ever been adopted so widely so quickly. The speed of uptake far exceeds that of the internet itself, let alone ancient technologies such as television or cinema or radio. Also amazing: as Facebook has grown, its users’ reliance on it has also grown. The increase in numbers is not, as one might expect, accompanied by a lower level of engagement. -

Iu3a Re-‐Thinking Economics Book Group Books Read Between

iU3A Re-thinking Economics Book Group Books Read between January 2019 and January 2020 Please note that not every member has read every book! Sometimes we choose one book, other times we choose a topic and, between us, read several. Topic When Title Author 2019 The need for January Doughnut Economics Kate Raworth rethinking economics Beliefs about the February The Production of Money Ann Pettifor nature of money The Joy of Tax Richard Murphy Debt: the first 5000 years David Graeber The dangers of March Austerity: (The History of a Mark Blyth unexamined beliefs Dangerous Idea) being turned into policy Introducing systems April The Fifth Discipline: the art Peter Senge science, chaos and and practice of the learning complexity theory (to organisation reflect on the paradigm different James Gleick economists are Chaos: Making a New Science working in) Andy Haldane; JB Rosser; Plus papers linking these to Jon Sterman; Joeri economics Schasfoort; Stevan Durlauf; Jon Palin; Alan Mills. The role of the State May Rethinking capitalism: An Michael Jacobs and in developing green introduction Mariana Mazzucato futures The Entrepreneurial State Marianna Mazzucato Heat, Need and Greed: Climate change, Capitalism add Ian Gough Sustainable Wellbeing A sociologist’s view of June The Future Of Capitalism Paul Collier today’s capitalism Lighter reading and Summer 1 23 things they don’t tell you Ha Joon Chang looking wider than about capitalism, and (July) the West Economics : the users guide, and Bad Samaritans: Guilty secrets of the rich nations and the threat to global security. The Globalisation paradox and Economics Rules Dani Rodrik An alternative to Summer 2 Bildung in the 21st Century: Jonathan Rowson, part conventional Growth Why sustainable prosperity of an essay series from (August) depends on re-imagining Tim Jackson’s Centre for education.