Away from Home Are Some and I—Homeplace in Fannie Flagg's

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Many Voices, One Nation Booklist A

Many Voices, One Nation Booklist Many Voices, One Nation began as an initiative of past American Library Association President Carol Brey-Casiano. In 2005 ALA Chapters, Ethnic Caucuses, and other ALA groups were asked to contribute annotated book selections that best represent the uniqueness, diversity, and/or heritage of their state, region or group. Selections are featured for children, young adults, and adults. The list is a sampling that showcases the diverse voices that exist in our nation and its literature. A Alabama Library Association Title: Send Me Down a Miracle Author: Han Nolan Publisher: San Diego: Harcourt Brace Date of Publication: 1996 ISBN#: [X] Young Adults Annotation: Adrienne Dabney, a flamboyant New York City artist, returns to Casper, Alabama, the sleepy, God-fearing town of her birth, to conduct an artistic experiment. Her big-city ways and artsy ideas aren't exactly embraced by the locals, but it's her claim of having had a vision of Jesus that splits the community. Deeply affected is fourteen- year-old Charity Pittman, daughter of a local preacher. Reverend Pittman thinks Adrienne is the devil incarnate while Charity thinks she's wonderful. Believer is pitted against nonbeliever and Charity finds herself caught in the middle, questioning her father, her religion, and herself. Alabama Library Association Title: Fried Green Tomatoes at the Whistle Stop Café Author: Fannie Flagg Publisher: New York: Random House Date of Publication: 1987 ISBN#: [X] Adults Annotation: This begins as the story of two women in the 1980s, of gray-headed Mrs. Threadgoode telling her life story to Evelyn who is caught in the sad slump of middle age. -

Georgia on My Screen Special FREE Events Saturday, July 13 at 3Pm Reel Magnolias: "Georgia’S Female Filmmakers"

For Immediate Release Date: July 12, 2019 Contact: Tony Clark, 404-865-7109 [email protected] News 19-12 Georgia On My Screen Special FREE Events Saturday, July 13 at 3pm Reel Magnolias: "Georgia’s Female Filmmakers" Saturday, August 10 from 10:00am-4:00pm... Strange Saturday Wednesday, August 13th at 6:30pm...Fried Green Tomatoes Saturday, August 31 at 3:00pm... Reel Magnolias:"Behind the Glamour: Film Production" Tuesday, October 1 at 6:30pm...Smokey and the Bandit Saturday, November 9 at 1pm...Ant Man and the Wasp Saturday, November 16 at 3:00pm...Reel Magnolias: "Creating the Illusion: Location Scouting and Set Design” Saturday, July 13th at 3pm Reel Magnolias: Georgia’s Female Filmmakers “Looking the Part: Makeup and Costume Design” While Actors and Directors lend their talents to bringing the substance of characters to life, the equation is not complete without Makeup Artists and Costume Designers. Join for the second installment of this panel series to hear from women who help create the “illusion.” Panelists will include accomplished industry professionals: Denise & Janice Tunnell: Make-Up Artists, Atlanta, Hunger Games, Furious 7, Captain America; Sekinah Brown: Costume Designer, Almost Christmas, Being Mary Jane, Night School, Ride Along. Moderator: Francesca Amiker, 11 Alive’s “The A-Scene” Saturday, August 10th 10am-4:00pm STRANGE Saturday HAS STRANGER THINGS SEASON 3 LEFT YOU PINING FOR THE 80s? Join us Saturday, August 10th in the lobby and live out your Stranger Things fantasies with FREE arcade games (including games used on the show), live Dungeons & Dragons, A Stranger Things Costume Contest and trivia with prizes, a vintage photo booth with FREE photos-- all to the soundtrack of the 80s! Stranger Things swag courtesy of Netflix. -

Fried Green Tomatoes (1991) 87 Liked It Average Rating: 3.7/5 User Ratings: 133,466 Movie Info

Fried Green Tomatoes (1991) 87 liked it Average Rating: 3.7/5 User Ratings: 133,466 Movie Info A woman learns the value of friendship as she hears the story of two women and how their friendship shaped their lives in this warm comedy-drama. Evelyn Couch (Kathy Bates) is an emotionally repressed housewife with a habit of drowning her sorrows in candy bars. Her husband Ed (Gailard Sartain) barely acknowledges her existence, and while he visits his aunt at a nursing home every week, Evelyn is not permitted to come into the room because the old women doesn't like her. One week, while waiting out Ed's visit, Evelyn meets Ninny Threadgoode (Jessica Tandy), a frail but feisty old woman who lives at the same nursing home and loves to tell stories. Over the span of several weeks, she spins a whopper about one of her relatives, Idgie (Mary Stuart Masterson). Back in the 1920s, Idgie was a sweet but fiercely independent woman with her own way of doing things who ran the town diner in Whistle Stop, Alabama. Idgie was very close to her brother Buddy (Chris O'Donnell), and when he died, she wouldn't talk to anyone except Buddy's girl, Ruth Jamison (Mary-Louise Parker). Idgie gave Ruth a job at the cafe after she left her abusive husband, Frank Theatrical release poster (Wikipedia) Bennett (Nick Searcy). Between her habit of standing up for herself, standing up to Frank, and serving food TOMATOMETER to Black people out the back of the diner, Idgie raised the ire of the less tolerant citizens of Whistle Stop, and when Frank mysteriously disappeared, many All Critics locals suspected that Idgie, Ruth, and their friends may have been responsible. -

Fannie Flagg: a Southern Treasure

GET TO KNOW FANNIE FLAGG “Hello! I’m thrilled to talk to anyone from Alabama!” Fannie Flagg’s distinctive, warm Southern voice says A outhern from the other end of the receiver. It’s a dreary day S in Birmingham, but there’s no doubt Flagg’s sunny disposition could part the clouds and bring the Treasure sunshine anytime. “I was worried about the storm! I thought ‘Oh no, maybe I won’t be able to get WITH WIT, WISDOM, AND A WHOLE through!’” It’s this upbeat nature that has become a hallmark of the legendary author. She’s personal and LOT OF SOUTHERN CHARM, THIS present in her conversations, like you’re just catching LEGENDARY AUTHOR, ACTRESS, up with an old friend. The course of her 50-plus-year career has seen Alabama’s own Fannie Flagg conquer AND ALABAMA NATIVE HAS MADE just about every facet of the entertainment industry HER MARK IN THE ENTERTAINMENT and more than solidify herself as a Southern treasure. She’s had roles in TV shows and movies including INDUSTRY WHILE STAYING The Love Boat, The New Dick Van Dyke Show, and TRUE TO HER ROOTS. Grease; taken a turn on Broadway in the musical The Best Little Whorehouse in Texas; and was a staple on classic game shows including Hollywood Squares, To Tell the Truth, and Match Game. But she’s always found her way back home to Alabama, and to her one true love—writing. Flagg has authored numerous novels: Daisy Fay and the Miracle Man; Standing in the Rainbow; A Redbird Christmas; Welcome to the World, Baby Girl!; Can’t Wait to Get to Heaven; I Still Dream About You; The All-Girl Filling Station’s Last Reunion; and her most recent, The Whole Town’s Talking. -

"FRIED GREEN TOMATOES": FRIENDSHIP AS GOD 309 L.Eliz.Dr., Craigville, MA 02636 Phone 508.775.8008 His First Sermon Was on Tolerance

Norman fear's 1hir0 sermon 2543 14 Mar 92 ELLIOTT THINKSHEETS "FRIED GREEN TOMATOES": FRIENDSHIP AS GOD 309 L.Eliz.Dr., Craigville, MA 02636 Phone 508.775.8008 His first sermon was on tolerance. "All in the Family"'s Noncommercial reproduction permitted Archie Bunker was a paragon of the opposing vice. He was the virtue's antihero in this sermon-story on what not to be & do. The value-field was social, the goal being a more amicable, multicultural common life. The downside of the sermon was its downputting of (1) the family & (2) fathers. Social philosophers continue to debate which it did more of, good or harm. It certainly pandered to the anti-institutional mood of the rising generation. ....Lear's second sermon was on freedom, its value-field political. It was his creation for People of the American Way, his version of "the American way" being radical secular humanism....His third sermon is on friendship, its value-field per- sonal. Based on Fannie Flagg's feminist novel, "Fried Green Tomatoes at the Whistle Stop Cafe." Lear's current film completes the sermon trilogy & rounds out his theology, such as it is. My review of it is unpolluted by other reviews: I haven't read or heard any yet....Why bother? Because Lear is the most powerful living individual shaper of American life. 1 Theotropism, turning to God, is Lear's central anti-value. Tolerance, freedom, friendship are alternative tropisms. What his next will be is anybody's guess. But this seems certain, barring a radical religious conversion: his virtues-list will always be secular; God in any traditional piety will not make it. -

'The Whole Town's Talking; a Novel' Download a Free Book Online

)FuaN-]] Download 'The Whole Town's Talking: A Novel' Download a Free Book Online ************************************************************************** ************************************************************************** Review [A] witty multigenerational saga . [Fannie] Flaggs down-home wisdom, her affable humor and her long view of life offer a pleasant respite in nerve-jangling times.PeopleThe Whole Towns Talking[is] Fannie Flagg at her best.Florida Times UnionI could not put this book down and didnt want the tale to end. Fannie Flagg does it again; a great read you wont want to miss.The MissourianIts a sweeping, cinematic approach. Flaggs gentle storytelling makes the novel an easy, comfortable read that will leave a reader thinking about life, love and lossMinneapolisStar Tribune[Fannie Flagg] creates a world familiar in its reality and its hopes, and she displays her storytelling skills, ones that are enhanced by her humanity, her optimism and her big heart. .The Whole Towns Talking[is] a story of lifes peaks, valleys and ordinary daysand a ringing affirmation of love, community and life itself.Richmond Times-DispatchThe Whole Towns Talkingis warm and inviting. Flaggs Elmwood Springs novels are comfort reads of the best kind, warm and engaging without flash or fuss.Miami HeraldFlaggs humor shines through as she chronicles their successes, disappointments, and even a mysterious murder or two. The interwoven lives of these completely engaging characters twist and turn in unexpected ways, making this chronicle of a close-knit community a pleasure to read.BookPage[A] charming tale.BooklistPraise for Fannie Flagg A born storyteller.The New York Times Book Review Read more About the Author Fannie Flaggs career started in the fifth grade when she wrote, directed, and starred in her first play, titled The Whoopee Girls, and she has not stopped since. -

Allende, Elizabeth – Daughter of Fortune

BOOK CLUB COLLECTION Fiction The Age of Innocence – Edith Wharton – Winner of the Pulitzer Prize 265 pages, also available-large print, eBook, cdbook, Playaway, eAudio, DVD, guide in penguin.com Edith Wharton's most famous novel, written immediately after the end of the First World War, is a brilliantly realized anatomy of New York society in the 1870s. The charming Newland Archer is content to live within its constraints until he meets Ellen Olenska, whose arrival threatens his impending marriage as well as his comfortable future. (publisher) The Alchemist – Paulo Coelho 177 pages, also available-large print, eBook, guide in book The charming tale of Santiago, a shepherd boy, who dreams of seeing the world, is compelling in its own right, but gains resonance through the many lessons Santiago learns during his adventures. He journeys from Spain to Morocco in search of worldly success, and eventually to Egypt, where a fateful encounter with an alchemist brings him at last to self-understanding and spiritual enlightenment. The story has the comic charm, dramatic tension and psychological intensity of a fairy tale, but it's full of specific wisdom as well, about becoming self-empowered, overcoming depression, and believing in dreams. (PW) Alias Grace – Margaret Atwood 468 pages, also available-large print, eBook, guide in readinggroupguides.com A finalist for the Booker Prize, a national best-seller by the author of The Handmaid's Tale tells the story of an enigmatic Victorian woman accused of a double murder and the psychologist who treats her. All the Bright Places- Jennifer Niven 388 pages, also available eBook, cd book, Playaway, eAudio Theodore Finch is fascinated by death, and he constantly thinks of ways he might kill himself. -

GREENSBURG HEMPFIELD AREA LIBRARY BOOK CLUBS RECOMMENDED TITLES (Number of Available Items Subject to Change)

GREENSBURG HEMPFIELD AREA LIBRARY BOOK CLUBS RECOMMENDED TITLES (Number of available items subject to change) stan = standard book, LP = large print, BCD = book on CD 1. 1776 David McCullough 2005 NON-FICTION 386 pgs. 30 stan, 1 LP, 3 BCD BasEd on extensive research in both American and British archives, 1776 is the story of Americans in thE ranks, mEn of EvEry shapE, size, and color, farmErs, schoolteachErs, shoEmakers, no-accounts, and merE boys turned soldiErs. And it is the story of the British commandEr, William HowE, and his highly disciplinEd redcoats who lookEd on thEir rebEl foEs with contEmpt and fought with a valor too littlE known. But it is thE American commandEr-in-chiEf who stands forEmost -- Washington, who had nEvEr bEforE lEd an army in battlE. 2. Accidental Empress, The Allison Pataki 2015 HISTORICAL FICTION 495 p. 8 stan ThE NEw York TimEs bEst-selling author of ThE Traitor's WifE fictionalizEs thE littlE-known and tumultuous lovE story of "Sisi," thE 19th-century Austro-Hungarian empress and captivating wifE of EmpEror Franz JosEph. 3. All-Girl Filling Station’s Last Reunion FanniE Flagg 2013 FICTION 17 stan, 4 LP, 8 BCD Spanning dEcadEs, gEnErations, and America in thE 1940s and today, a fun-loving mystEry about an Alabama woman today and fivE women who in 1943 workEd in a Phillips 66 gas station during thE WWII yEars. LikE FanniE Flagg's classic Fried Green Tomatoes, this is a rivEting, fun story of two familiEs, sEt in prEsEnt day America and during World War II, fillEd to thE brim with Flagg's tradEmark funny voicE and storytelling magic. -

Fannie Flagg's Fried Green Tomatoes at the Whistle Stop Cafe

FANNIE FLAGG’S FRIED GREEN TOMATOES AT THE WHISTLE STOP CAFE: GENDER, CLASS, RACE AND WHITE SUPREMACY BY MR. NATTHAPOL BOONYAOUDOMSART A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS (ENGLISH LANGUAGE STUDIES) DEPARTMENT OF ENGLISH AND LINGUISTICS FACULTY OF LIBERAL ARTS THAMMASAT UNIVERSITY ACADEMIC YEAR 2017 COPYRIGHT OF THAMMASAT UNIVERSITY Ref. code: 25605706040119AWJ FANNIE FLAGG’S FRIED GREEN TOMATOES AT THE WHISTLE STOP CAFE: GENDER, CLASS, RACE AND WHITE SUPREMACY BY MR. NATTHAPOL BOONYAOUDOMSART A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS (ENGLISH LANGUAGE STUDIES) DEPARTMENT OF ENGLISH AND LINGUISTICS FACULTY OF LIBERAL ARTS THAMMASAT UNIVERSITY ACADEMIC YEAR 2017 COPYRIGHT OF THAMMASAT UNIVERSITY Ref. code: 25605706040119AWJ (1) Thesis Title FANNIE FLAGG’S FRIED GREEN TOMATOES AT THE WHISTLE STOP CAFE: GENDER, CLASS, RACE AND WHITE SUPREMACY Author Mr. Natthapol Boonyaoudomsart Degree Master of Arts Major Field/Faculty/University English Language Studies Faculty of Liberal Arts Thammasat University Thesis Advisor Assistant Professor Suriyan Panlay, Ph.D. Academic Year 2017 ABSTRACT Deploying Black feminist criticism as a theoretical framework, this thesis essentially presents literary characters’ encounter with manifestations of oppression and their struggles for liberation in Fannie Flagg’s Fried Green Tomatoes at the Whistle Stop Cafe. First, it sets out to explore sexist, classist and racist ideologies that, through a lens of intersectionality, give rise to a complication of subordination that needs to be contested. Next, my close reading of the novel reveals that the expression of intense rootedness translates into fictional characters’ collective effort in affirming their resistance, thereby retaining a deep meaning of homeplace as a site of opposition. -

New York Times Best Seller List – Week of March 7, 2021 FICTION NONFICTION TW LW WOL TW LW WOL a COURT of SILVER FLAMES, by Sarah J

New York Times Best Seller List – Week of March 7, 2021 FICTION NONFICTION TW LW WOL TW LW WOL A COURT OF SILVER FLAMES, by Sarah J. Maas. 5th book HOW TO AVOID A CLIMATE DISASTER, by Bill 1 in A Court of Thorn and Roses series. Nesta Archeron is -- 1 O/O 1 Gates. A prescription for what business, governments -- 1 forced into close quarters with a warrior named Cassian. and individuals can do to work toward zero emissions. THE FOUR WINDS, by Kristin Hannah. As dust storms roll JUST AS I AM, by Cicely Tyson. The late iconic 2 during the Great Depression, Elsa must choose between 1 3 actress describes how she worked to change 2 2 4 saving the family and farm or heading West. perceptions of Black women through her career THE MIDNIGHT LIBRARY, by Matt Haig. Nora Seed finds a choices. 3 library beyond the edge of the universe that contains books 3 12 THE SUM OF US, by Heather McGhee. The chair of with multiple possibilities of the lives one could have lived. O/O the board of the racial justice organization Color of -- 1 THE VANISHING HALF, by Brit Bennett. The lives of twin 3 Change analyzes the impact of racism on the sisters who run away from a Southern Black community at economy. 4 5 38 age 16 diverge as one returns and the other takes on a WALK IN MY COMBAT BOOTS, by James Patterson different racial identity but their fates intertwine. O/O 4 and Matt Eversmann with Chris Mooney. -

New York Times Best Seller List – Week of April 4, 2021 FICTION NONFICTION TW LW WOL TW LW WOL WIN, by Harlan Coben

New York Times Best Seller List – Week of April 4, 2021 FICTION NONFICTION TW LW WOL TW LW WOL WIN, by Harlan Coben. Windsor Horne Lockwood III might THIS IS THE FIRE, by Don Lemon. CNN host looks 1 rectify cold cases connected to his family that have eluded -- 1 O/O 1 at the impact of racism on his life and prescribes ways -- 1 the F.B.I. for decades. to address systemic flaws in America. THE FOUR WINDS, by Kristin Hannah. As dust storms roll THE CODE BREAKER, by Walter Isaacson. How the 2 during the Great Depression, Elsa must choose between 2 7 Nobel Prize winner Jennifer Doudna and her 2 1 2 saving the family and farm or heading West. colleagues invented CRISPR, a tool that can edit LIFE AFTER DEATH, by Sister Souljah. In a sequel to “The DNA. 3 Coldest Winter Ever,” Winter Santiaga emerges after time 1 3 GREENLIGHTS, by Matthew McConaughey. The served and seeks revenge. 3 Academy Award winning actor shares snippets from 3 22 THE MIDNIGHT LIBRARY, by Matt Haig. Nora Seed finds a the diaries he kept over the last 35 years. 4 library beyond the edge of the universe that contains books 3 16 CASTE, by Isabel Wilkerson. Pulitzer Prize-winning with multiple possibilities of the lives one could have lived. journalist examines aspects of caste systems across 4 4 33 KLARA AND THE SUN, by Kazuo Ishiguro. An “Artificial civilizations and reveals a rigid hierarchy in America O/O today. 5 Friend” named Klara is purchased to serve as a companion 4 3 to an ailing 14-year-old girl. -

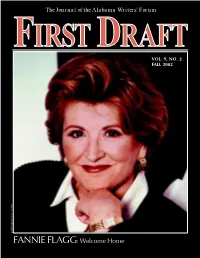

Vol.9, No.2 / Fall 2002

The Journal of the Alabama Writers’ Forum NAME OF ARTICLE 1 FIRST DRAFT VOL. 9, NO. 2 FALL 2002 COPYRIGHT SUZE LANIER FANNIE FLAGG: Welcome Home 2NAME OF ARTICLE? From the Editor FY 02 The Alabama Writer’s Forum BOARD OF DIRECTORS President PETER HUGGINS Auburn Vice-President BETTYE FORBUS Dothan Secretary LINDA HENRY DEAN Auburn First Draft Welcomes Treasurer New Editors Jay Lamar FAIRLEY MCDONALD Montgomery Writers’ Representative We are pleased to announce two new book review editors for the coming AILEEN HENDERSON Brookwood year. Jennifer Horne will be Poetry editor, and Derryn Moten will serve as Ala- Writers’ Representative bama and Southern History editor. Horne’s publications include a chapbook, DARYL BROWN Florence Miss Betty’s School of Dance (bluestocking press, 1997), and poems in Ama- JULIE FRIEDMAN ryllis, Astarte, the Birmingham Poetry Review, Blue Pitcher (poetry prize Fairhope 1992), and Carolina Quarterly, among other journals. An MFA graduate of the STUART FLYNN Birmingham University of Alabama, Horne has taught college English, been an artist in ED GEORGE residence, and served as a journal, magazine, and book editor. She is currently Montgomery pursuing a master’s in community counseling. JOHN HAFNER Mobile Moten is associate professor of Humanities at WILLIAM E. HICKS Alabama State University and holds a Ph.D. and Troy RICK JOURNEY an MA in American Studies from the University Birmingham of Iowa, as well as an MS in Library Science DERRYN MOTEN Montgomery from Catholic University of America. Recent DON NOBLE publications include “When the ‘Past Is Not Tuscaloosa Even the Past’: The Rhetoric of a Southern His- STEVE SEWELL Birmingham torical Marker” (Professing Rhetoric, Lawrence PHILIP SHIRLEY Erlbaum Associates, 2002) as well as “To Live Jackson, Mississippi Derryn Moten and Die in Dixie: Alabama and the Electric LEE TAYLOR Monroeville Chair” (Alabama Heritage, 2001).