Changing Ballet

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Caramel Variations by Ian Spencer Bell from Ballet Review Spring 2012 Cover Photograph by Stephanie Berger, BAM : Silas Riener in Merce Cunningham’S Split Sides

Spring 2012 Ball et Review The Caramel Variations by Ian Spencer Bell from Ballet Review Spring 2012 Cover Photograph by Stephanie Berger, BAM : Silas Riener in Merce Cunningham’s Split Sides . © 2012 Dance Research Foundation, Inc. All rights reserved. 4 Moscow – Clement Crisp 5 Chicago – Joseph Houseal 6 Oslo – Peter Sparling 9 Washington, D. C. – George Jackson 10 Boston – Jeffrey Gantz 12 Toronto – Gary Smith 13 Ann Arbor – Peter Sparling 16 Toronto – Gary Smith 17 New York – George Jackson Ian Spencer Bell 31 18 The Caramel Variations Darrell Wilkins 31 Malakhov’s La Péri Francis Mason 38 Armgard von Bardeleben on Graham Don Daniels 41 The Iron Shoe Joel Lobenthal 64 46 A Conversation with Nicolai Hansen Ballet Review 40.1 Leigh Witchel Spring 2012 51 A Parisian Spring Editor and Designer: Marvin Hoshino Francis Mason Managing Editor: 55 Erick Hawkins on Graham Roberta Hellman Joseph Houseal Senior Editor: 59 The Ecstatic Flight of Lin Hwa-min Don Daniels Associate Editor: Emily Hite Joel Lobenthal 64 Yvonne Mounsey: Encounters with Mr B 46 Associate Editor: Nicole Dekle Collins Larry Kaplan 71 Psyché and Phèdre Copy Editor: Barbara Palfy Sandra Genter Photographers: 74 Next Wave Tom Brazil Costas 82 London Reporter – Clement Crisp 89 More Balanchine Variations – Jay Rogoff Associates: Peter Anastos 90 Pina – Jeffrey Gantz Robert Gres kovic 92 Body of a Dancer – Jay Rogoff George Jackson 93 Music on Disc – George Dorris Elizabeth Kendall 71 100 Check It Out Paul Parish Nancy Reynolds James Sutton David Vaughan Edward Willinger Cover Photograph by Stephanie Berger, BAM : Silas Riener Sarah C. -

Ballet Terms Definition

Fundamentals of Ballet, Dance 10AB, Professor Sheree King BALLET TERMS DEFINITION A la seconde One of eight directions of the body, in which the foot is placed in second position and the arms are outstretched to second position. (ah la suh-GAWND) A Terre Literally the Earth. The leg is in contact with the floor. Arabesque One of the basic poses in ballet. It is a position of the body, in profile, supported on one leg, with the other leg extended behind and at right angles to it, and the arms held in various harmonious positions creating the longest possible line along the body. Attitude A pose on one leg with the other lifted in back, the knee bent at an angle of ninety degrees and well turned out so that the knee is higher than the foot. The arm on the side of the raised leg is held over the held in a curved position while the other arm is extended to the side (ah-tee-TEWD) Adagio A French word meaning at ease or leisure. In dancing, its main meaning is series of exercises following the center practice, consisting of a succession of slow and graceful movements. (ah-DAHZ-EO) Allegro Fast or quick. Center floor allegro variations incorporate small and large jumps. Allonge´ Extended, outstretched. As for example, in arabesque allongé. Assemble´ Assembled or joined together. A step in which the working foot slides well along the ground before being swept into the air. As the foot goes into the air the dancer pushes off the floor with the supporting leg, extending the toes. -

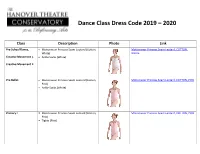

Dance Class Dress Code 2019 – 2020

Dance Class Dress Code 2019 – 2020 Class Description Photo Link Pre-School Dance, Motionwear Princess Seam Leotard (Cotton, Motionwear Princess Seam Leotard, COTTON, White) WHITE Creative Movement I, Ankle Socks (White) Creative Movement II Pre-Ballet Motionwear Princess Seam Leotard (Cotton, Motionwear Princess Seam Leotard, COTTON, PINK Pink) Ankle Socks (White) Primary I . Motionwear Princess Seam Leotard (Cotton, Motionwear Princess Seam Leotard, COTTON, PINK Pink) . Tights (Pink) Primary II . Motionwear Princess Seam Leotard (Cotton, Motionwear Princess Seam Leotard, COTTON, Light Blue) LIGHT BLUE . Tights (Pink) Primary III . Motionwear Princess Seam Leotard Motionwear Princess Seam Leotard, SILKSKYN, (Silkskyn, Royal Blue) ROYAL BLUE . Tights (Pink) Teen Ballet & . Motionwear Princess Seam Leotard Motionwear Princess Seam Leotard, SILKSKYN, (Silkskyn, Hunter Green) HUNTER GREEN Adult Ballet II . Tights (Pink) Level A . Motionwear Princess Seam Leotard Motionwear Princess Seam Leotard, SILKSKYN, (Silkskyn, Fuchsia) FUCHSIA . Tights (Pink) Level B . Motionwear Princess Seam Leotard Motionwear Princess Seam Leotard, SILKSKYN, (Silkskyn, Bright Red) BRIGHT RED . Tights (Pink) Level C . Motionwear Princess Seam Leotard Motionwear Princess Seam Leotard, SILKSKYN, (Silkskyn, Maroon) MAROON . Tights (Pink) Level D, . Motionwear Princess Seam Leotard Motionwear Princess Seam Leotard, SILKSKYN, (Silkskyn, Black) BLACK Boys & Girls Club, . Tights (Pink) Adult Ballet Youth Ballet Company . Motionwear Princess Seam Leotard (Cotton, Motionwear Princess Seam Leotard, COTTON, (Apprentice) Butter) BUTTER . Tights (Pink) Youth Ballet Company . Any style white leotard (Junior) . Tights (Pink) Youth Ballet Company . Any style black leotard (Senior) . On the 2nd Saturday of each month any color leotard is allowed. Tights (Pink) Boys Ballet . Motionwear Cap Sleeve Fitted T-Shirt . Motionwear Mens Cap Sleeve Fitted t-shirt, (Silkskyn, White) SILKSKYN, WHITE . -

Singapore Dance Theatre Presents Passages Contemporary Season 2019 1 – 3 November 2019 | Esplanade Theatre Studio

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE Singapore Dance Theatre presents Passages Contemporary Season 2019 1 – 3 November 2019 | Esplanade Theatre Studio World Premiere by Lucas Jervis Bittersweet by Natalie Weir Swipe by Val Caniparoli Blue Snow by Toru Shimazaki 05 August 2019 Blue Snow by Toru Shimazaki | Photo: Bernie Ng Singapore Dance Theatre (SDT) will be presenting its annual full contemporary season of the year, Passages, from 1 – 3 November at the Esplanade Theatre Studio. From electrifying to soulful works, this Season is set to grip you with its captivating line-up and leave you at the edge of your seats. Come and be inspired by these compelling and moving masterpieces. “Passages Contemporary Season has always had its unique personality and profile within the SDT performance calendar. It had most often been used to introduce choreographers that are new to our audiences and for the presentation of either world premieres or company premieres. It is a place that fills the spirit of the initial concept of SDT perfectly. Many of the ballets from Passages become significant parts of our permanent repertoire and we present them on tour or in future seasons. This year, we have two works that were previously made especially for SDT, with Natalie Weir’s Bittersweet and Toru Shimazaki’s Blue Snow, as well as Val Caniparoli’s Swipe. We also have a world premiere from an exciting Australian choreographer, Lucas Jervies, working with SDT for the first time. It is very exciting to have him represented within our repertoire with his new creation for our dancers.” says Artistic Director Janek Schergen. -

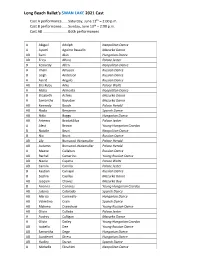

Swan Lake 2021 Cast List

Long Beach Ballet’s SWAN LAKE 2021 Cast Cast A performance ...... Saturday, June 12th – 2:00 p.m. Cast B performance ...... Sunday, June 13th – 2:00 p.m. Cast AB ......................... Both performances A Abigail Adolph Neopolitan Dance A Ayumi Aguirre Bassallo Mazurka Dance AB Sumi Akin Hungarian Dance AB Erica Alfaro Palace Jester B Kennedy Allen Neopolitan Dance A Imani Amyson Russian Dance B Leigh Anderson Russian Dance A Astrid Angulo Russian Dance AB Ella Ruby Arko Palace Waltz A Melia Armenta Neopolitan Dance B Elizabeth Ashley Mazurka Dance A Samantha Bayudan Mazurka Dance AB Kennedy Beach Palace Herald AB Nadia Benjamin Spansh Dance AB Nikki Boggs Hungarian Dance AB Artemis BrodakSilva Palace Jester A Alesi Brown Young Hungarian Czardas B Natalie Brunt Neopolitan Dance B Nia Brunt Russian Dance AB Lily Bumacod‐Weismuller Palace Herald AB Autumn Bumacod‐Weismuller Palace Herald A Maeve Callahan Russian Dance AB Rachel Camerino Young Russian Dance AB Nicole Capcha Palace Waltz AB Camila Carrillo Palace Jester B Kaytlan Carvajal Russian Dance B Sophia Casillas Mazurka Dance AB Joaquin Chavez Mazurka Boy B Arianna Cisneros Young Hungarian Czardas AB Juliana Colorado Spansh Dance AB Marisa Conneally Hungarian Dance AB Valentina Crain Spansh Dance AB Makena Crawshaw Young Russian Dance AB Olivia Cullado Palace Jester A Audrey Culligan Mazurka Dance A Olivia Dailey Young Hungarian Czardas AB Isabella Dee Young Russian Dance AB Samantha Dege Hungarian Dance AB Aundenet Diress Hungarian Dance AB Hadley Duzan Spansh Dance A Michelle -

Music, Dance and Swans the Influence Music Has on Two Choreographies of the Scene Pas D’Action (Act

Music, Dance and Swans The influence music has on two choreographies of the scene Pas d’action (Act. 2 No. 13-V) from Tchaikovsky’s Swan Lake Naam: Roselinde Wijnands Studentnummer: 5546036 BA Muziekwetenschap BA Eindwerkstuk, MU3V14004 Studiejaar 2017-2018, block 4 Begeleider: dr. Rebekah Ahrendt Deadline: June 15, 2018 Universiteit Utrecht 1 Abstract The relationship between music and dance has often been analysed, but this is usually done from the perspective of the discipline of either music or dance. Choreomusicology, the study of the relationship between dance and music, emerged as the field that studies works from both point of views. Choreographers usually choreograph the dance after the music is composed. Therefore, the music has taken the natural place of dominance above the choreography and can be said to influence the choreography. This research examines the influence that the music has on two choreographies of Pas d’action (act. 2 no. 13-V), one choreographed by Lev Ivanov, the other choreographed by Rudolf Nureyev from the ballet Swan Lake composed by Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky by conducting a choreomusicological analysis. A brief history of the field of choreomusicology is described before conducting the analyses. Central to these analyses are the important music and choreography accents, aligning dance steps alongside with musical analysis. Examples of the similarities and differences between the relationship between music and dance of the two choreographies are given. The influence music has on these choreographies will be discussed. The results are that in both the analyses an influence is seen in the way the choreography is built to the music and often follows the music rhythmically. -

Reviving Ballet in the Nineteenth Century: Music, Narrative, and Dance in Delibes's Coppélia by Arthur E. Lafex Submitted To

Reviving Ballet in the Nineteenth Century: Music, Narrative, and Dance in Delibes’s Coppélia By Copyright 2013 Arthur E. Lafex Submitted to the graduate degree program in Music and the Graduate Faculty of the University of Kansas in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Music. ________________________________ Chairperson Alicia Levin ________________________________ Paul R. Laird ________________________________ David Alan Street Date Defended: April 15, 2013 The Thesis Committee for Author (Arthur E. Lafex) certifies that this is the approved version of the following thesis: Reviving Ballet in the Nineteenth Century: Music, Narrative, and Dance in Delibes’s Coppélia ________________________________ Chairperson Alicia Levin Date approved: April 15, 2013 ii Abstract Léo Delibes (1836-1891) wrote ballet scores that have inspired composers and have entertained generations of ballet lovers. His scores have been cited for their tunefulness, appropriateness for their narrative, and for their danceability. However, Delibes remains an obscure figure in music history, outside the musical canon of the nineteenth century. Likewise, his ballet music, whose harmonic resources are conventional and whose forms are variants of basic structures, has not received much scholarly and theoretical attention. This thesis addresses Delibes’s music by examining his ballet score for Coppélia, its support of narrative and also its support of dance. Chapter 1 begins with a historical view of ballet and ballet music up to the time of Delibes. Following a biographical sketch of the composer, a review of aspects of the score for Giselle by his mentor, Adolphe Adam (1803-1856) establishes a background upon which Delibes’s ballets can be considered. -

Spring-Summer 2019 Ballet Review

Spring-Summer 2019 Ballet Review 4 Philadelphia – Eva Shan Chou 5 New York – Karen Greenspan 7 Los Angeles – Eva Shan Chou 9 New York – Susanna Sloat 11 Williamstown – Christine Temin 12 New York – Karen Greenspan Susanna Sloat 16 Tokyo – Vincent Le Baron 95 Rennie Harris and Ronald K. Brown 18 Jacob’s Pillow – Christine Temin Celebrate Alvin Ailey 20 Toronto – Gary Smith Robert Greskovic 22 Boston – Jeffrey Gantz 100 Chopiniana 25 London – Joseph Houseal 25 Vienna – Vincent Le Baron 109 Judson Dance Theater 27 New York – Susanna Sloat Michael Langlois 28 Miami – Michael Langlois 114 Awakenings 29 Toronto – Gary Smith 31 Venice – Joel Lobenthal Karen Greenspan 32 London – Gerald Dowler 119 In the Court of Yogyakarta 35 Havana – Gary Smith Marian Smith 37 Washington, D.C. – Lisa Traiger 125 The Metropolitan Balanchine 39 London – John Morrone 40 Chicago – Joseph Houseal Gerald Dowler 42 Milan – Vincent Le Baron 141 An Autumn in Europe Alexei Ratmansky Sophie Mintz 44 Staging Petipa’s Harlequinade 146 White Light at ABT Lynn Garafola George Washington Cable 151 Raymonda, 1946 56 The Dance in Place Congo Karen Greenspan Michael Langlois 161 Drive East 2018 63 A Conversation with Karen Greenspan Clement Crisp 168 A Conversation with Maya Joseph Houseal Kulkarni and Mesma Belsaré 76 A Quiet Evening, in Two Acts Francis Mason Ian Spencer Bell 171 Ben Belitt on Graham 82 Women Onstage Gary Smith Michael Langlois 175 A Conversation with Grettel Morejón 86 A Conversation with Hubert Goldschmidt Stella Abrera 177 Rodin and the Dance 207 London Reporter – Louise Levene 218 Dance in America – Jay Rogoff 220 Music on Disc – George Dorris Cover photo by Paul Kolnik, NYCB: Joseph Gordon in Dances at a Gathering. -

Guide to Dance 2018-2019 Study Guide

GUIDE TO DANCE 2018-2019 STUDY GUIDE Learn about the art of dance and go behind-the-scenes with a professional dance company. Written and compiled by Ambre Emory-Maier, Director of Education, and other contributors l ©2018 BalletMet Columbus TABLE OF CONTENTS Behind the Scenes ............................................................................................................................................. 2 Brief History of BalletMet ................................................................................................................................. 3 BalletMet Offerings ........................................................................................................................................... 4 The Five W’s and H of Dance .......................................................................................................................... 5 Brief History of Ballet ..................................................................................................................................... 6-7 Important Tutu Facts ......................................................................................................................................... 8 Important Pointe Shoe Facts .......................................................................................................................... 9 Glossary of Dance Terms ......................................................................................................................... 10-12 Ballet Terminology.......................................................................................................................................... -

Chapter 9 Ballet Edited.Ppt.Pdf

C H A P T E R 9 Ballet Chapter ?? Chapter 9 Ballet Enduring understanding: Ballet is a classic, Western dance genre and a performing art. Essential question: How does ballet help me express myself as a dancer? Learning Objectives •Recognize major ballet works, styles, and ballet artists in history. •Execute basic ballet technique, use ballet vocabulary, and perform barre exercises and center combinations. •Apply ballet etiquette and dance safety while dancing. •Evaluate and respond to classical and contemporary ballet performances. Introduction Ballet began as a Western classical dance genre 400 years ago and has evolved into an international performing art form. The word ballet comes from the Italian term ballare, meaning to dance. Chapter 9 Vocabulary Terms adagio allegro à la seconde à terre ballet ballet technique barre center derrière stage directions Devant turnout en l’air Ballet Beginnings Ballet moved from Italy to France when Catherine de’ Medici married the heir to the French throne, King Henry II. She produced what has become known as the first ballet, La Comique de la Reine, in 1588. Ballet at the French Court Louis XIV performed as a dancer and gained the title The Sun King after one of his most famous dancing roles. A patron of the arts, Louis XIV established the Academy of Music and Dance. In the next century the Academy would become the Paris Opéra. Court Ballets • During the 17th century, court ballets were dance interludes between dramatic or vocal performances or entire performances. • Sometimes ballets were part of themed balls such as pastoral or masquerade balls. -

Ballet Hispanico at the Joyce, Program B

http://www.edgenewyork.com/index.php?ch=entertainment&sc=theatre&sc2=reviews&sc3=&id =143258 Ballet Hispanico at the Joyce, Program B Saturday Apr 27, 2013 - By Steve Weinstein If my EDGE review of Ballet Hispanico’s Program A at the just-completed season at the Joyce was less than ecstatic, I had no such qualms when experiencing the sheer joy of "Ballet Hispanico: Program B." The three separate works showed how profoundly this American troupe has spanned the wide world of Latino dance and distilled it to its essence. Vanessa Valecillo and Jamal Rashann Callender in ’Tango Vitrola’ (Source:Paula Lobo) From the moment that a male soloist appeared on the stage, his arms clasped high over his head - - those defiant gestures that define flamenco -- I was prepared to enter the world of flamenco. Derived from several sources, over its long history, flamenco assimilated gypsy and folk dances, put it into the small neighborhood clubs of Andalusia and turned it into an art form. Normally, flamenco is accompanied by singer-shouters who rhythmically clap their hands in a quirky syncopation. The last all-flamenco program I saw put too much emphasis on the singing, with the dancing appearing and re-appearing at intervals. This might be more authentic, but makes less of a pure dance experience. Ballet Hispanico’s "Nube Blanco" dispensed with traditional dialect singing in favor of a more dance-oriented score by Maria Dolores Pradera, all to the good. The audience was able to experience pure flamenco moves uninterrupted by long periods of singing and clapping. -

Whether You Try Ballet, Tango, Or Just Freestyle with Your Friends, Dancing

Leisure Whether you try ballet, Tango, or just freestyle with Dancing gets a 10 your friends, dancing of any fro m Le n sort confers some hile not everyone may be as incredible as tap, jazz, contemporary, bedroom freestyle, or zumba. With an incredible health Michael Flatley, everybody and anybody open mind, you’ll be rocking it on the dance floor in no time! can benefit from giving dance a try. According to a recent survey by the Royal Academy of benefits Whether you try ballet, tango, or just Dance the older you get the less embarrassed you are Wfreestyle with your friends, dancing of any sort confers some to dance. incredible health benefits. Melanie Murphy, RAD’s Director of Marketing Improve learning and memory. Dancing and learning Communications & Membership, said: “The results of this dances activates the cognitive centre of the brain and survey reinforce how dance can help to build self-confidence encourages neural plasticity. This means that neurons are at any age. Our research team within the Faculty of Education healthier and more adaptable throughout life, meaning better have undertaken extensive research into the health and cognitive function as you age. Especially in later years, wellbeing benefits of dance under its Dance for Lifelong skills and neurons enhanced through dance are incredibly Wellbeing project, with one key audience being the 60 plus important in maintaining memory function. It is also one of market. In response to the research last year, we launched a the few forms of physical activity that effectively protects programme of Silver Swans™ classes to meet the demand against dementia.