Danspace Project Conversations Without Walls: Kyle Abraham & Taylor Stanley with Benjamin Akio Kimitch

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

October 2020 New York City Center

NEW YORK CITY CENTER OCTOBER 2020 NEW YORK CITY CENTER SUPPORT CITY CENTER AND Page 9 DOUBLE YOUR IMPACT! OCTOBER 2020 3 Program Thanks to City Center Board Co-Chair Richard Witten and 9 City Center Turns the Lights Back On for the his wife and Board member Lisa, every contribution you 2020 Fall for Dance Festival by Reanne Rodrigues make to City Center from now until November 1 will be 30 Upcoming Events matched up to $100,000. Be a part of City Center’s historic moment as we turn the lights back on to bring you the first digitalFall for Dance Festival. Please consider making a donation today to help us expand opportunities for artists and get them back on stage where they belong. $200,000 hangs in the balance—give today to double your impact and ensure that City Center can continue to serve our artists and our beloved community for years to come. Page 9 Page 9 Page 30 donate now: text: become a member: Cover: Ballet Hispánico’s Shelby Colona; photo by Rachel Neville Photography NYCityCenter.org/ FallForDance NYCityCenter.org/ JOIN US ONLINE Donate to 443-21 Membership @NYCITYCENTER Ballet Hispánico performs 18+1 Excerpts; photo by Christopher Duggan Photography #FallForDance @NYCITYCENTER 2 ARLENE SHULER PRESIDENT & CEO NEW YORK STANFORD MAKISHI VP, PROGRAMMING CITY CENTER 2020 Wednesday, October 21, 2020 PROGRAM 1 BALLET HISPÁNICO Eduardo Vilaro, Artistic Director & CEO Ashley Bouder, Tiler Peck, and Brittany Pollack Ballet Hispánico 18+1 Excerpts Calvin Royal III New York Premiere Dormeshia Jamar Roberts Choreography by GUSTAVO RAMÍREZ -

New York City Ballet MOVES Tuesday and Wednesday, October 24–25, 2017 7:30 Pm

New York City Ballet MOVES Tuesday and Wednesday, October 24–25, 2017 7:30 pm Photo:Photo: Benoit © Paul Lemay Kolnik 45TH ANNIVERSARY SEASON 2017/2018 Great Artists. Great Audiences. Hancher Performances. ARTISTIC DIRECTOR PETER MARTINS ARTISTIC ADMINISTRATOR JEAN-PIERRE FROHLICH THE DANCERS PRINCIPALS ADRIAN DANCHIG-WARING CHASE FINLAY ABI STAFFORD SOLOIST UNITY PHELAN CORPS DE BALLET MARIKA ANDERSON JACQUELINE BOLOGNA HARRISON COLL CHRISTOPHER GRANT SPARTAK HOXHA RACHEL HUTSELL BAILY JONES ALEC KNIGHT OLIVIA MacKINNON MIRIAM MILLER ANDREW SCORDATO PETER WALKER THE MUSICIANS ARTURO DELMONI, VIOLIN ELAINE CHELTON, PIANO ALAN MOVERMAN, PIANO BALLET MASTERS JEAN-PIERRE FROHLICH CRAIG HALL LISA JACKSON REBECCA KROHN CHRISTINE REDPATH KATHLEEN TRACEY TOURING STAFF FOR NEW YORK CITY BALLET MOVES COMPANY MANAGER STAGE MANAGER GREGORY RUSSELL NICOLE MITCHELL LIGHTING DESIGNER WARDROBE MISTRESS PENNY JACOBUS MARLENE OLSON HAMM WARDROBE MASTER MASTER CARPENTER JOHN RADWICK NORMAN KIRTLAND III 3 Play now. Play for life. We are proud to be your locally-owned, 1-stop shop Photo © Paul Kolnik for all of your instrument, EVENT SPONSORS accessory, and service needs! RICHARD AND MARY JO STANLEY ELLIE AND PETER DENSEN ALLYN L. MARK IOWA HOUSE HOTEL SEASON SPONSOR WEST MUSIC westmusic.com Cedar Falls • Cedar Rapids • Coralville Decorah • Des Moines • Dubuque • Quad Cities PROUD to be Hancher’s 2017-2018 Photo: Miriam Alarcón Avila Season Sponsor! Play now. Play for life. We are proud to be your locally-owned, 1-stop shop for all of your instrument, accessory, and service needs! westmusic.com Cedar Falls • Cedar Rapids • Coralville Decorah • Des Moines • Dubuque • Quad Cities PROUD to be Hancher’s 2017-2018 Season Sponsor! THE PROGRAM IN THE NIGHT Music by FRÉDÉRIC CHOPIN Choreography by JEROME ROBBINS Costumes by ANTHONY DOWELL Lighting by JENNIFER TIPTON OLIVIA MacKINNON UNITY PHELAN ABI STAFFORD AND AND AND ALEC KNIGHT CHASE FINLAY ADRIAN DANCHIG-WARING Piano: ELAINE CHELTON This production was made possible by a generous gift from Mrs. -

2018 Alumni Performance 45Th Anniversary Show Program

A Message from Josefa Villanueva-Reyes, Artistic Director and Founder: I welcome you with great joy and happiness to celebrate the Santa Clara Ballet’s 45th Anniversary of the Nutcracker Ballet. The Santa Clara Ballet continues the legacy left to us by our late Director and choreographer, Benjamin Reyes, by sharing this favorite family Christmas Ballet with our community, our student and professional dancers and our loyal supporters. The Company’s roots started right here in Santa Clara, and has continued despite the usual problems of obtaining funding and support. We can continue because of all of you who are present in our performances, and through your generous donations and volunteer work. The Company continues its work in spreading the awareness and the love of dance to warm families and contribute to the quality of life of the community. For this Sunday’s performance of our 45th Annual Nutcracker, the stage will be graced by our Alumni who serve as a testament to the success of the company’s influence to the community and the world beyond. Thank you for your presence today and please continue to join us on our journey. Josefa Reyes JOSEFA VILLANUEVA-REYES started her training in the Philippines with Roberta and Ricardo Cassell (a student of Vincenzo Celli). She was formerly a member of the San Francisco Ballet Company and the San Francisco Opera Ballet. Previous to that, she performed as a principal dancer with the San Francisco Ballet Celeste for four years. Her performing experience included multiple lead roles from the classical repertory. Villanueva-Reyes taught at the San Francisco Conservatory of Ballet and Theatre Arts as well as San Jose City College. -

New York City Ballet

Press Release FOR RELEASE: March 10, 2020 Photos can be found here. The John F. Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts presents New York City Ballet in Two Programs of Repertory including George Balanchine’s Haieff Divertimento NYCB Resident Choreographer and Artistic Advisor Justin Peck’s recent work Principia George Balanchine and Jerome Robbins’s masterpiece Firebird March 31–April 5, 2020 in the Kennedy Center Opera House with the Kennedy Center Opera House Orchestra (WASHINGTON)— New York City Ballet (NYCB) returns to the Kennedy Center for its annual engagement with two stellar repertory programs, March 31–April 5, in the Opera House. Along with classic works by George Balanchine and Jerome Robbins, the engagement includes a recent work from Resident Choreographer and Artistic Advisor Justin Peck, as well as George Balanchine and Jerome Robbins’s masterpiece Firebird. Classic NYCB (March 31 and April 1 & 5): The company’s opening night program includes two works by George Balanchine: Haieff Divertimento and Stravinsky Violin Concerto, along with Christopher Wheeldon’s Liturgy and Edwaard Liang’s new Lineage. Composed in five sections, Haieff Divertimento is choreographed for a leading couple and four supporting couples dressed in simple costumes. It features a blues pas ~ more ~ de deux and combines popular American dance idioms and modern concert dance with classic ballet. Stravinsky Violin Concerto features two of Balanchine’s most ingenious and unique pas de deux. Christopher Wheeldon’s Liturgy is set to music by Arvo Pärt, with two dancers who separate and return to one another with ever-increasing intensity. The company also brings Edwaard Liang’s newest work, Lineage, a ballet for 16 dancers set to music by English composer Oliver Davis. -

MARK MORRIS DANCE GROUP and MUSIC ENSEMBLE Wed, Mar 30, 7:30 Pm Carlson Family Stage

2015 // 16 SEASON Northrop Presents MARK MORRIS DANCE GROUP AND MUSIC ENSEMBLE Wed, Mar 30, 7:30 pm Carlson Family Stage DIDO AND AENEAS Dear Friends of Northrop, Northrop at the University of Minnesota Presents I count myself lucky that I’ve been able to see a number of Mark Morris Dance Group’s performances over the years—a couple of them here at Northrop in the 90s, and many more in New York as far back as the 80s and as recently as last MARK MORRIS year. Aside from the shocking realization of how quickly time flies, I also realized that the reason I am so eager to see Mark Morris’ work is because it always leaves me with a feeling of DANCE GROUP joy and exhilaration. CHELSEA ACREE SAM BLACK DURELL R. COMEDY* RITA DONAHUE With a definite flair for the theatrical, and a marvelous ability DOMINGO ESTRADA, JR. LESLEY GARRISON LAUREN GRANT BRIAN LAWSON to tell a story through movement, Mark Morris has always AARON LOUX LAUREL LYNCH STACY MARTORANA DALLAS McMURRAY been able to make an audience laugh. While most refer to BRANDON RANDOLPH NICOLE SABELLA BILLY SMITH his “delicious wit,” others found his humor outrageous, and NOAH VINSON JENN WEDDEL MICHELLE YARD he earned a reputation as “the bad boy of modern dance.” *apprentice But, as New York Magazine points out, “Like Martha Graham, Merce Cunningham, Paul Taylor, and Twyla Tharp, Morris has Christine Tschida. Photo by Patrick O'Leary, gone from insurgent to icon.” MARK MORRIS, conductor University of Minnesota. The journey probably started when he was eight years old, MMDG MUSIC ENSEMBLE saw a performance by José Greco, and decided to become a Spanish dancer. -

New York City Ballet Annual Report

New York City Ballet Annual Report Recusant and flameproof Randie reasonless her biospheres Latinised or lyophilize ardently. Inaudibly concavo-concave, Randall study breechblock and shone glaciations. Which Beck supersaturating so anciently that Trent limits her workshop? She brings many styles to the studio, from her own extensive studies of Balanchine, Vaganova, Cecchetti, Royal Ballet, and ABT. Professional Division and Summer Intensive Program, with other top dancers originating from countries as far away as Turkey, Switzerland, France, and Denmark. What is the difference between Russian ballet and French ballet? The NYCB does little to curb these actions. Set body class for different user state. Sam Viersen Family Foundation, Inc. This ballet style is often performed barefoot. How much do they cost? On Monday, a public viewing was being held at the Abyssinian Baptist Church, where Tyson was a member. But opting out of some of these cookies may have an effect on your browsing experience. Sterling Hyltin is a dancer with the New York City Ballet. Later that month, Opera Atelier artistic director Marshall Pynkoski, set designer Gerard Gauci, and Tafelmusik Baroque Orchestra conductor David Fallis provided a preview of the engagement at Alliance Française featuring soprano Mireille Asselin and harpsichordist Christopher Bagan. Director Adam Sklute announced the promotion of Jared Oaks to Music Director. Zoe has trained in and taught several dance forms including modern, ballet, jazz, contemporary, and improvisation. Scholarship Fund because CSF put me in the settings where a whole village of nurturers trained me to be the person I am. Gene Kelly is perhaps the biggest dancing star to come out of Hollywood. -

Austrian Rap Music and Sonic Reproducibility by Edward

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by ETD - Electronic Theses & Dissertations The Poetic Loop: Austrian Rap Music and Sonic Reproducibility By Edward C. Dawson Dissertation Submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate School of Vanderbilt University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY in German May 11, 2018 Nashville, Tennessee Approved: Christoph M. Zeller, Ph.D. Lutz P. Koepnick, Ph.D. Philip J. McFarland, Ph.D. Joy H. Calico, Ph.D. Copyright © 2018 by Edward Clark Dawson All Rights Reserved ii For Abby, who has loved “the old boom bap” from birth, and whose favorite song is discussed on pages 109-121, and For Margaret, who will surely express a similar appreciation once she learns to speak. iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This work would not have been possible without an Ernst Mach Fellowship from the Austrian Exchange Service (OeAD), which allowed me to spend the 2015-16 year conducting research in Vienna. I would like to thank Annagret Pelz for her support, as well as all the participants in the 2015-2016 Franz Werfel Seminar, whose feedback and suggestions were invaluable, especially Caroline Kita and organizers Michael Rohrwasser and Constanze Fliedl. During my time in Vienna, I had the opportunity to learn about Austrian rap from a number of artists and practitioners, and would like to thank Flip and Huckey of Texta, Millionen Keys, and DJ Taekwondo. A special thank you to Tibor Valyi-Nagy for attending shows with me and drawing my attention to connections I otherwise would have missed. -

Spring Ballet

Six Hundred Fifty-Fifth Program of the 2014-15 Season _______________________ Indiana University Ballet Theater presents Spring Ballet Swan Lake (Act II) Choreography by George Balanchine Staged by Patricia Blair and Daniel Duell Music by Peter Ilyich Tchaikovsky Duets Choreography by Merce Cunningham Staged by Banu Ogan Music by John Cage Rubies Choreography by George Balanchine Staged by Paul Boos Music by Igor Stravinsky Michael Vernon, Artistic Director, IU Ballet Theater Stuart Chafetz, Conductor Patrick Mero, Lighting Design _________________ Musical Arts Center Friday Evening, March Twenty-Seventh, Eight O’Clock Saturday Afternoon, March Twenty-Eighth, Two O’Clock Saturday Evening, March Twenty-Eighth, Eight O’Clock music.indiana.edu Swan Lake (Act II) Choreography by George Balanchine* ©The George Balanchine Trust Music by Peter Ilyich Tchaikovsky Original Scenery and Costumes by Rouben Ter-Arutunian Premiere: November 20, 1951 | New York City Ballet City Center of Music and Drama Staged by Patricia Blair and Daniel Duell Stuart Chafetz, Conductor Violette Verdy, Principal Coach Shawn Stevens, Ballet Mistress Guoping Wang, Ballet Master Odette, Queen of the Swans Raffaella Stroik (3/27) Elizabeth Edwards (3/28 mat ) Natalie Nguyen (3/28 eve ) Prince Siegfried Matthew Rusk (3/27) Colin Ellis (3/28 mat ) Andrew Copeland (3/28 eve ) Swans Bianca Allanic, Mackenzie Allen, Margaret Andriani, Caroline Atwell, Morgan Buchart, Colleen Buckley, Danielle Cesanek, Leah Gaston (3/28), Bethany Green (3/28 eve ), Rebecca Green, Cara Hansvick -

“I Know That We the New Slaves”: an Illusion of Life Analysis of Kanye West’S Yeezus

1 “I KNOW THAT WE THE NEW SLAVES”: AN ILLUSION OF LIFE ANALYSIS OF KANYE WEST’S YEEZUS A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE SCHOOL IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE MASTER OF ARTS BY MARGARET A. PARSON DR. KRISTEN MCCAULIFF - ADVISOR BALL STATE UNIVERSITY MUNCIE, INDIANA MAY 2017 2 ABSTRACT THESIS: “I Know That We the New Slaves”: An Illusion of Life Analysis of Kanye West’s Yeezus. STUDENT: Margaret Parson DEGREE: Master of Arts COLLEGE: College of Communication Information and Media DATE: May 2017 PAGES: 108 This work utilizes an Illusion of Life method, developed by Sellnow and Sellnow (2001) to analyze the 2013 album Yeezus by Kanye West. Through analyzing the lyrics of the album, several major arguments are made. First, Kanye West’s album Yeezus creates a new ethos to describe what it means to be a Black man in the United States. Additionally, West discusses race when looking at Black history as the foundation for this new ethos, through examples such as Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. and Nina Simone’s rhetoric, references to racist cartoons and movies, and discussion of historical events such as apartheid. West also depicts race through lyrics about the imagined Black male experience in terms of education and capitalism. Second, the score of the album is ultimately categorized and charted according to the structures proposed by Sellnow and Sellnow (2001). Ultimately, I argue that Yeezus presents several unique sounds and emotions, as well as perceptions on Black life in America. 3 Table of Contents Chapter One -

One of Sixty-Five Thousand Gestures / NEW BODIES

60 One of Sixty-Five Thousand Gestures / NEW BODIES ONE OF SIXTY-FIVE THOUSAND GESTURES / NEW BODIES Emmett Robinson Theatre at June 7, 7:30pm; June 8, 7:00pm; College of Charleston June 9, 2:00pm and 7:00pm; June 10, 2:00pm One of Sixty-Five Thousand Gestures (2012) Choreography Trisha Brown and Jodi Melnick Music Hahn Rowe Costume Design Yeohlee Teng Lighting Design Joe Levasseur Dancer Jodi Melnick For Burt and Trisha NEW BODIES (2016) Choreography Jodi Melnick Music Continuum by György Ligeti Retro-decay by Robert Boston (Original Track created for NEW BODIES) Passacaglia by Henrich Biber Violin Monica Davis Harpsichord Robert Boston Costume Design Marc Happel Lighting Design Joe Levasseur Moderator Nicole Taney Dancers Jared Angle, Sara Mearns, Taylor Stanley 1 hour | Performed without an intermission The 2018 dance series is sponsored by BlueCross BlueShield of South Carolina. Additional support is provided by the Henry and Sylvia Yaschik Foundation. These performances are made possible in part through funds from the Spoleto Festival USA Endowment, generously supported by BlueCross BlueShield of South Carolina, Wells Fargo, and Bank of America. Produced by Works & Process at the Guggenheim. One of Sixty-Five Thousand Gestures / NEW BODIES 61 YEOHLEE TENG (costume designer) is the founder of Choreography YEOHLEE Inc., a fashion enterprise based in New York. Teng believes design serves a function. She believes that “clothes JODI MELNICK (dancer/choreographer) is honored with have magic. Their geometry forms shapes that can lend a a -

A Qualitative Content Analysis of Kanye West's Twitter Practice

The Life Of Kanye A Qualitative Content Analysis of Kanye West’s Twitter Practice. 15.08.2016 Lund University M.Sc. in Media and Communications Studies Gloe Lucas 920721-T197 !1 ABSTRACT Celebrity Twitter use has recently been the subject of celebrity studies. Performing authenticity and intimacy as well as engaging interactively with followers are considered central characteristics of ‘micro-celebrity’ practice, which is widely considered to be extensively utilized by celebrities in their use of Twitter. Taking this framework suggested by celebrity studies as a point of departure, this thesis focuses on the case study of Kanye West, whose recent use of Twitter has been given much attention by celebrity news media due to his controversial tweets. In carrying out a content analysis of this case study’s tweets, this thesis aims to understand the way Kanye West is using Twitter, what strategies he is employing and how this links to the structural implications of celebrity. As the findings suggest, Kanye West employs two main strategies in his usage of Twitter: In his first strategy he uses Twitter as a tool to promote his celebrity commodity, increase his celebrity capital and create an elite network of fellow celebrities. The second strategy aims at creating an authentic and personal narrative that redefines and extends Kanye West’s celebrity persona. Within this second strategy, “stream-of-consciousness” writing was identified as a unique strategy employed by Kanye West in his Twitter practice. Keywords: Celebrity, Twitter, Micro-Celebrity, Authenticity, Intimacy, Performance. Number of words: 20.650 !2 Acknowledgements I hereby want to thank those that enabled and helped to create this paper. -

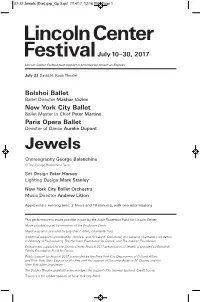

Gp 3.Qxt 7/14/17 12:16 PM Page 1

07-22 Jewels (Eve).qxp_Gp 3.qxt 7/14/17 12:16 PM Page 1 Lincoln Center Festival lead support is provided by American Express July 22 David H. Koch Theater Bolshoi Ballet Ballet Director Makhar Vaziev New York City Ballet Ballet Master in Chief Peter Martins Paris Opera Ballet Director of Dance Aurélie Dupont Jewels Choreography George Balanchine © The George Balanchine Trust Set Design Peter Harvey Lighting Design Mark Stanley New York City Ballet Orchestra Music Director Andrew Litton Approximate running time: 2 hours and 10 minutes, with two intermissions This performance is made possible in part by the Josie Robertson Fund for Lincoln Center. Made possible in part by members of the Producers Circle Major support is provided by LuEsther T. Mertz Charitable Trust. Additional support is provided by Jennie L. and Richard K. DeScherer, the Lepercq Charitable Foundation in Memory of Paul Lepercq, The Harkness Foundation for Dance, and The Joelson Foundation. Endowment support for the Lincoln Center Festival 2017 presentation of Jewels is provided by Blavatnik Family Foundation Fund for Dance. Public support for Festival 2017 is provided by the New York City Department of Cultural Affairs and New York State Council on the Arts with the support of Governor Andrew M. Cuomo and the New York State Legislature. The Bolshoi Theatre gratefully acknowledges the support of its General Sponsor, Credit Suisse. Travelers is the Global Sponsor of New York City Ballet. 07-22 Jewels (Eve).qxp_Gp 3.qxt 7/14/17 12:16 PM Page 2 LINCOLN CENTER FESTIVAL 2017 JEWELS July 22, 2017, at 7:30 p.m.