Personal Injury Torts Between Spouses

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

That Is the Question! Postaccident Police Investigations

TRUCKING LAW To Cooperate or Not… That Is the Question! Postaccident Police By Brian Del Gatto Investigations and Julia Paridis Use of response teams, Consider the following hypothetical scenario. A driver as well as driver training, for your motor carrier client is headed to a rest stop for a can limit potentially much-needed break. Before moving into the exit-only lane, damaging statements. he or she checks his or her rear- and side-view mirrors and doesn’t notice any cars in the lane to his or The next few minutes are crucial and will her right. As the driver signals to change have a profound impact on the ultimate out- lanes and moves right into the exit lane, come of this matter for the driver, the motor the driver’s phone rings, and he or she looks carrier, and the insurers of each. down for a second to determine who it is. The driver then looks up just as the right- Postaccident Investigations front passenger side of the tractor collides The policeman on the beat or in the with the left-back driver side of a four-door patrol car makes more decisions and sedan. exercises broader discretion affecting The motor carrier’s driver pulls over and the daily lives of people every day and is confronted by someone yelling, “You hit to a greater extent, in many respects, me!” The person complains of neck and than a judge will ordinarily exercise in back pain and calls 911. The ambulance a week. arrives and places the sedan driver on a —Warren E. -

A New Look at Contract Mistake Doctrine and Personal Injury Releases

19 NEV. L.J. 535, GIESEL 4/25/2019 8:36 PM A NEW LOOK AT CONTRACT MISTAKE DOCTRINE AND PERSONAL INJURY RELEASES Grace M. Giesel* “[C]ourts cannot make for the parties better agreements than they themselves have been satisfied to make.”1 TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................... 536 I. THE SETTING: THE TYPICAL CASE ..................................................... 542 II. CONTRACT DOCTRINE APPLIES .......................................................... 544 III. CONTRACT MISTAKE DOCTRINE ......................................................... 545 IV. TRADITIONAL APPLICATION OF CONTRACT DOCTRINE TO THE TYPICAL PERSONAL INJURY RELEASE SITUATION.............................. 547 A. A Shared Mistake of Fact and Not a Speculation or Prediction . 547 B. The Injured Party Has the Risk of Mistake by Conscious Ignorance .................................................................................... 548 C. The Release Places the Risk of Mistake on the Injured Party ..... 549 D. Traditional Application of the Unilateral Mistake Doctrine to the Typical Personal Injury Release Situation ............................ 554 E. Conclusions about Traditional Application of the Mistake Doctrine ...................................................................................... 555 V. COURTS’ TREATMENT OF PERSONAL INJURY RELEASES .................... 555 A. Mistake Doctrine Applies with an Unknown Injury But Not with an Unknown Consequence of a Known Injury ................... -

Contingency Fee Retainer Agreement (Personal Injury)

Contingency Fee Retainer Agreement (Personal Injury) This document incorporates more than two dozen required clauses further to the Solicitors Act, R.S.O. 1990, c.S.15, Contingency Fee Agreements, O. Reg. 195/04. This document should be adapted to suit your practice and the matter for which it is being used. See endnote. [Firm Name, Address, Telephone Number, Email] [Date] [Client Name] [Client Address] Re: Accident of [date of accident] Part 1: Our Services Legal services covered by this contract [Firm Name and/or Lawyer Name] is being retained by the client to provide the following services and to represent the client in respect to injuries, losses and damages resulting from a [type of accident] which occurred on or about [date]. We agree to act for you in your legal claim against [name of Defendant(s)], once we receive a signed and dated copy of this contract. We will then be your lawyers throughout the whole legal process including going to trial if necessary. (The attached document called Steps in a Lawsuit explains the basic steps most lawsuits go through as well as some legal terms.) The limitation period, or the latest date by which we will commence a lawsuit, is [Day, Month, Year]. At the same time, we will try to settle your case to obtain a favourable settlement for you. A settlement is an agreement between the parties to a lawsuit which sets out how they will resolve the claim. If your claim is settled, it will not have to go to trial. We will keep you informed about matters that arise, and discuss with you any significant decisions you must make. -

The Virginia Car Accident Guide: a Former Insurance Lawyer’S Guide to Auto Accident Injury Claims

The Virginia Car Accident Guide: A Former Insurance Lawyer’s Guide to Auto Accident Injury Claims: By James R. Parrish, Esquire If you are reading this book then CONGRATULATIONS! You have taken the first step to obtaining a better understanding of the automobile accident personal injury claims process. This book is designed to educate you about this area of the law and teach you how the insurance companies operate. Over the last several years, the insurance industry has spent millions (maybe billions) of dollars successfully brainwashing the general public to believe that people who make personal injury claims are lazy, good for nothing men and women just looking for a “free ride” and “easy money.” In fact, the insurance companies will go to almost any length to prevent you from successfully pursuing your claim. I know this because I used to defend insurance companies and worked intimately with everyone in the insurance industry from front-line adjusters to corporate “big wigs.” I used to lecture to insurance professionals to help them more successfully settle claims for small amounts or deny claims altogether. I wrote articles for insurance/risk management companies. I even graduated from the International Association of Defense Counsel trial academy! This book is written with knowledge I gained from all of my interactions with the insurance companies with which I now do battle on behalf of people injured in car accidents. It is my hope that the information contained within this book will arm you with the knowledge you will need if you have been injured in an automobile accident and deserve to recover compensation for those injuries. -

EQUITABLE JURISDICTION to PROTECT PERSONAL RIGHTS Joseph R

YALE LAW JOURNAL Vol. XXXIII DECEMBER, 1923 No. 2 EQUITABLE JURISDICTION TO PROTECT PERSONAL RIGHTS JosEPH R. LONG It is a curious fact in the history of the court of equity that certain limitations upon its jurisdiction have been insistently declared by text- writers and judges which are not only contrary to the fundamental theory of equitable jurisdiction, but also have no substantial foundation in the actual decisions and practice of the courts. Among these anoma- lous limitations may be mentioned the doctrines that a court of equity will not grant relief against a pure mistake of law; that it will never enforce a forfeiture; and that it has no jurisdiction to protect personal rights where no property rights are involved. After a long struggle the courts of equity have now about broken away from the unsound doctrines that they cannot grant relief against mistakes of law nor enforce forfeitures, and there are clear signs that the equally unsound doctrine that they have no jurisdiction to protect personal rights will soon be abandoned. The unreasonableness of so arbitrary and unjust a doctrine that a court of equity will protect one in his rights of contract and property, but deny protection to his far more sacred and vital rights of person, has often been commented upon, but the unsubstantial char- acter of the foundation upon which this doctrine rests has not been so generally recognized. Until recently it was inevitable that the jurisdiction of the court of equity should, in practice, have been almost entirely confined to the protection of property rights. -

Speaking for the Dead: Voice in Last Wills and Testaments Karen J

St. John's Law Review Volume 85 Article 12 Issue 2 Volume 85, Spring 2011, Number 2 April 2014 Speaking for the Dead: Voice in Last Wills and Testaments Karen J. Sneddon Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarship.law.stjohns.edu/lawreview Recommended Citation Sneddon, Karen J. (2014) "Speaking for the Dead: Voice in Last Wills and Testaments," St. John's Law Review: Vol. 85: Iss. 2, Article 12. Available at: http://scholarship.law.stjohns.edu/lawreview/vol85/iss2/12 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at St. John's Law Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in St. John's Law Review by an authorized administrator of St. John's Law Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ARTICLE SPEAKING FOR THE DEAD: VOICE IN LAST WILLS AND TESTAMENTS KARENJ. SNEDDONt INTRODUCTION ................................. ..... 684 I. FUNCTION OF WILLS ........................... .......685 II. VOICE ..................................... ...... 689 A. Term Defined. ...................... ....... 689 B. Applicability of Voice to Wills ............ ..... 696 C. Pitfalls.......................... ........ 708 D. Benefits ............................ ..... 720 III. VOICE IN WILLS ........................... ..... 728 A. Voice in Non-Attorney Drafted Wills ...... ...... 728 1. Nuncupative Wills ................. ...... 729 2. Ethical Wills...... ................. 729 3. Holographic Wills .................. ..... 732 4. Commercial Fill-in-the-Blank Forms and -

Nber Working Paper Series Economic Analysis Of

NBER WORKING PAPER SERIES ECONOMIC ANALYSIS OF ACCIDENT LAW Steven Shavell Working Paper 9694 http://www.nber.org/papers/w9694 NATIONAL BUREAU OF ECONOMIC RESEARCH 1050 Massachusetts Avenue Cambridge, MA 02138 May 2003 Research support from the John M. Olin Center for Law, Economics, and Business is gratefully acknowledged.The views expressed herein are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the National Bureau of Economic Research. ©2003 by Steven Shavell. All rights reserved. Short sections of text not to exceed two paragraphs, may be quoted without explicit permission provided that full credit including ©notice, is given to the source. Economic Analysis of Accident Law Steven Shavell NBER Working Paper No. 9694 May 2003 JEL No. D00, D8, K13 ABSTRACT Accident law is the body of legal rules governing the ability of victims of harm to sue and to collect payments from those who injured them. This paper contains the chapters on accident law from a general, forthcoming book, Foundations of Economic Analysis of Law (Harvard University Press, 2003). The analysis is first concerned (chapters 2-4) with the influence of liability rules on incentives to reduce accident risks. Then consideration of accident law is broadened (chapter 5) to reflect the effect of liability rules on compensation of victims and the allocation of risk. In this regard a central issue is the roles of victims’ insurance and of liability insurance, and how they alter the incentives inherent in liability rules. Finally, the administrative costs of the liability system, namely, the private and public legal costs of litigation, are examined (chapter 6). -

Settlement/Mediation Considerations & Strategies in Trucking

SETTLEMENT/MEDIATION CONSIDERATIONS & STRATEGIES IN TRUCKING OR AUTO ACCIDENT CASES Presented & Written By: FRANK E. (DIRK) MURCHISON III Frank E. Murchison P.C. Lubbock, TX Office: P.O. Drawer 98600 Lubbock TX 79499 806.792.4870 806.792.4970 Fax Taos, NM Office: P.O. Drawer 700 Taos NM 87571 575.751.3156 575.751.3157 Fax [email protected] State Bar of Texas PROSECUTING OR DEFENDING A TRUCKING OR AUTO ACCIDENT CASE November 15-16, 2012 San Antonio CHAPTER 15 FRANK E. MURCHISON, P.C. FRANK E. (DIRK) MURCHISON III Attorney at Law Lubbock, TX Office: Taos, NM Office: P.O. Drawer 98600 P.O. Drawer 700 Lubbock, TX 79499 Taos, NM 87571 806.792.4870 575.751.3156 806.792.4970 Fax Fax 575.751.3157 _______________________________________________________________________________________________________ EDUCATIONAL BACKGROUND: BBA: (Finance) Texas Tech University 1971 J.D.: Texas Tech University School of Law 1974 LICENSURE: Texas: 1974; New Mexico: 2012 BOARD CERTIFICATIONS: Board Certified – Civil Trial Law & Personal Injury Trial Law Texas Board of Legal Specialization PROFESSIONAL MEMBERSHIPS & HONORS: Fellow --- American College of Trial Lawyers Best Lawyers in America --- Arbitration & Mediation 2012 Texas Lawyer of the Year-- 1 of 4 Selected Diplomate --- American Board of Trial Advocates Texas Super Lawyer --- Alternate Dispute Resolution Member --- Civil Trial Advisory Commission Texas Board of Specialization 1987-1992 PROFESSIONAL PRACTICE & EXPERIENCE: 1974-2001: Approximately 100 cases tried to jury verdict as lead counsel 2001-Present: Practice limited to arbitration & mediation of catastrophic personal injury and complex commercial, estate, trust, employment and sexual abuse cases Mediator in Mike Leach V. Texas Tech University; Over 850 cases arbitrated or mediated, including approximately 40 clergy sexual abuse cases successfully mediated. -

2020 Spring Newsletter

ARDITO & ARDITO ATTORNEYS AT LAW Spring 2020 We’d like to connect WE PROVIDE THE SERVICE with you via email! If you’d prefer to receive YOU GET THE RESULTS our future publications Ardito & Ardito Attorneys at Law is an experienced full service law electronically, please send us an email at: firm established specifically to provide professional, personal and [email protected] effective legal services to our clients. Inside this issue: COVID-19 UPDATE All of us at Ardito & Ardito hope that you, your family, loved ones, COVID-19 Information 2 for Clients friends and co-workers are all safe during these unprecedented times; and that you are finding a way to cope with the new “normal” as our lives have 3 been transformed in a way we never could have imagined. Estate and Although the end of this crisis may not be in sight, we must all do our best Asset Planning to remain positive and continue to cautiously assist those in need, such as the elderly or persons with underlying conditions, as well as taking the Our thank you: 4 threat from this illness very seriously for ourselves and others by complying COVID-19 Good “Will” with all recommended safety measures. Drive We would like you to know that our office remains functional and we continue to serve our clients as their needs arise in the midst of this pandemic by reviewing and updating existing estate planning documents, or assisting with creating planning documents for the first time. Need legal advice? Mention this newsletter The state and federal governments have implemented certain acts and to receive a free half hour mandates to provide some relief to those affected such as: consultation. -

5 Secrets Insurance Companies Don't Want You to Know

Dear Friend: If you (or someone you care about) have been injured in an accident, you are probably worrying about what to do next. Chances are, you are feeling angry that a stranger has suddenly turned your life upside down. You may be frustrated that no one is stepping forward to take care of the situation. Shortly after an accident, you will probably be contacted by an insurance adjuster. You may be asking: “Can I trust the insurance company to settle my claim fairly?” You might be wondering whether it makes sense to talk to a lawyer about your legal rights. Regardless of whether you choose to deal with the insurance company on your own or decide to get a lawyer, you are going to have many questions. Since 1984, we have been devoted to the aggressive and ethical representation of people who have suffered harm due to the negligence of others. Over the years, we’ve become increasingly frustrated about how hard it is for accident victims to get straight answers to their questions after an accident. We’ve learned that many accident victims cause irreparable harm to their legal claim because they decide to deal with the insurance company directly before obtaining legal advice. Making a claim for personal injuries has become such a hassle that many people just “give up” and don’t try to fight for what they deserve. It is our sincere hope that this informational letter will help you learn the important things that you should, and should not do, after being involved in an accident. -

Virginia Model Jury Instructions – Civil

Virginia Model Jury Instructions – Civil Release 20, March 2020 NOTICE TO USERS: THE FOLLOWING SET OF UNANNOTATED MODEL JURY INSTRUCTIONS ARE BEING MADE AVAILABLE WITH THE PERMISSION OF THE PUBLISHER, MATTHEW BENDER & COMPANY, INC. PLEASE NOTE THAT THE FULL ANNOTATED VERSION OF THESE MODEL JURY INSTRUCTIONS IS AVAILABLE FOR PURCHASE FROM MATTHEW BENDER® BY WAY OF THE FOLLOWING LINK: https://store.lexisnexis.com/categories/area-of-practice/civil-procedure- 154/virginia-model-jury-instructions-civil-skuusSku7357 Matthew Bender is a registered trademark of Matthew Bender & Company, Inc. Instruction No. 2.000 Preliminary Instructions to Jury Members of the jury, the order of the trial of this case will be in four stages: 1. Opening statements 2. Presentation of the evidence 3. Instructions of law 4. Final argument After the conclusion of final argument, I will instruct you concerning your deliberations. You will then go to your room, select a foreperson, deliberate, and arrive at your verdict. Opening Statements The plaintiff's attorney may make an opening statement outlining the plaintiff's case. Then the defendant's attorney also may make an opening statement. Neither side is required to do so. Presentation of the Evidence Following the opening statements, the plaintiff will introduce evidence, after which the defendant then has the right to introduce evidence (but is not required to do so). Rebuttal evidence may then be introduced if appropriate. Instructions of Law At the conclusion of all evidence, I will instruct you on the law which is to be applied to this case. Final Argument Once the evidence has been presented and you have been instructed on the law, then the attorneys may make their closing arguments. -

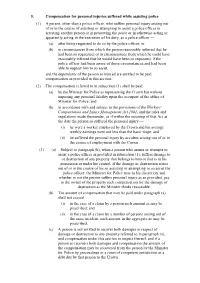

5. Compensation for Personal Injuries Suffered While Assisting Police (1) A

5. Compensation for personal injuries suffered while assisting police (1) A person, other than a police officer, who suffers personal injury arising out of or in the course of assisting or attempting to assist a police officer in arresting another person or in preserving the peace or in otherwise acting or apparently acting in the execution of his duty, as a police officer — (a) after being requested to do so by the police officer; or (b) in circumstances from which the person reasonably inferred that he had been so requested, or in circumstances from which he could have reasonably inferred that he would have been so requested, if the police officer had been aware of those circumstances and had been able to request him to so assist, and the dependants of the person so injured are entitled to be paid compensation as provided in this section. (2) The compensation referred to in subsection (1) shall be paid — (a) by the Minister for Police as representing the Crown but without imposing any personal liability upon the occupant of the office of Minister for Police; and (b) in accordance with and subject to the provisions of the Workers’ Compensation and Injury Management Act 1981, and the rules and regulations made thereunder, as if within the meaning of that Act at the date the person so suffered the personal injury — (i) he were a worker employed by the Crown and his average weekly earnings were not less than the basic wage; and (ii) he suffered the personal injury by accident arising out of or in the course of employment with the Crown.