Naomi Thesis 28 Januari 2017.Pages

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

PCSO Nabs Shooting Suspect After Chase

Mostly sunny INSIDE 5% chance of rain MATURE TODAY | If you are over 50 85 65 or planning to be. For details, see 2A www.mypdn.com PALATKA DAILY NEWS SATURDAY, OCTOBER 24, 2015 $1 PCSO nabs PANTHER shooting suspect PARTY after chase 23-year-old fled, but was arrested at an apartment BY ALLISON WATERS-MERRITT Palatka Daily News CHRIS DEVITTO/Palatka Daily News Palatka High cheerleaders helped lead the homecoming parade along St. Johns Avenue on Friday afternoon. A suspect accused in multiple Palatka area shootings in July was arrested Friday afternoon. During Putnam County Sheriff’s Office Capt. halftime, Another year, another Gator DeLoach said Latelvin Anthony Dontaevone Hightower, 23, was arrest- Evans and ed in an apartment on Kennedy homecoming: Palatka Bainbridge Road. Rainge were The suspect was seen named celebrated the annual high leaving the same apart- Palatka ment earlier by undercov- High’s er officers from the Drug homecoming school event with a parade, and Vice Unit who were king and working on a different queen. investigation, Sheriff’s a football game and, of Hightower ALLISON WATERS- Office Capt. Joe Wells MERRITT/Palatka Daily News said. course, the crowning of a “He got into a car in front of (the officers),” Wells said. new king and queen DeLoach said a marked patrol car attempted to stop the suspect, which led to a short pursuit. During the pursuit, DeLoach said officers saw the suspect throw a bag containing two oxycodone pills from the vehicle. See NABS, Page 5A File photo by CHRIS DEVITTO/Palatka Daily News City officials resolved an issue with cemeteries by compromising with area funeral homes. -

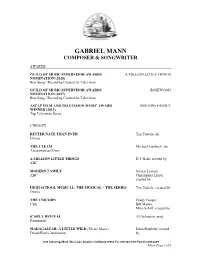

Gabriel Mann Composer & Songwriter

GABRIEL MANN COMPOSER & SONGWRITER AWARDS GUILD OF MUSIC SUPERVISOR AWARDS A MILLION LITTLE THINGS NOMINATION (2020) Best Song / Recording Created for Television GUILD OF MUSIC SUPERVISOR AWARDS ROSEWOOD NOMINATION (2017) Best Song / Recording Created for Television ASCAP FILM AND TELEVISION MUSIC AWARD MODERN FAMILY WINNER (2013) Top Television Series CREDITS BETTER NATE THAN EVER Tim Federle, dir. Disney THE J TEAM MicHael Lembeck, dir. Awesomeness Films A MILLION LITTLE THINGS D.J. NasH, created by ABC MODERN FAMILY Steven Levitan, ABC ChristopHer Lloyd, created by HIGH SCHOOL MUSICAL: THE MUSICAL – THE SERIES Tim Federle, created by Disney THE UNICORN Grady Cooper, CBS Bill Martin, Mike ScHiff, created by iCARLY REVIVAL Ali ScHouten, prod. Paramount+ MADAGASCAR: A LITTLE WILD (Theme Music) Dana Starfield, created DreamWorks Animation by 3349 Cahuenga Blvd. West, Los Angeles, California 90068 Tel. 818-380-1918 Fax 818-380-2609 Mann Page 1 of 6 GABRIEL MANN COMPOSER & SONGWRITER CREDITS (continued) CLEOPATRA IN SPACE (Main Title Theme By) Judge Plummer, prod. Peacock SIDE HUSTLE (Theme Song) David Malkoff, created Nickelodeon by CAROL’S SECOND ACT Emily Halpern, SaraH CBS Haskins, created by DELILAH James Griffiths, dir. HBO Max MERRY HAPPY WHATEVER Tucker Cawley, created Netflix by PRINCE OF PEORIA Devin Bunje, Nick Netflix Stanton, created by FAM Corinne Kingsbury, CBS created by ARRESTED DEVELOPMENT (Songs By) MitcHell Hurwitz, Fox created by SCREECHERS WILD! Todd Resnick, dir. AlpHa Group LEGEND OF THREE CABALLEROS Matt Danner, Douglas Disney Television Animation Lovelace, Greg Franklin, dirs. HUMOR ME Sam Hoffman, dir. Shout! Factory NELLA THE PRINCESS KNIGHT (Theme Song, Songs By) Christine Ricci, created Nickelodeon by 3349 Cahuenga Blvd. -

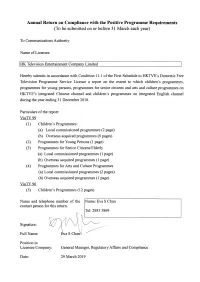

Annual Return on Compliance with the Positive Programme Requirements (To Be Submitted on Or Before 31 March Each Year)

Annual Return on Compliance with the Positive Programme Requirements (To be submitted on or before 31 March each year) To Communications Authority Name ofLicensee |HK Television E帥rtainment Comp叫出 ited Hereby submits in acωrdance with Condition 11.1 ofthe First Schedule to HKTVE's Domestic Free Television Programme Service Licence a repo此 on the extent to which children's programmes, programmes for young persons, programrnes for senior citizens and arts and culture programmes on HKTVE's integrated Chinese channel and children's programmes on integrated English channel during the year ending 31 December 2018. Particulars of the report ViuTV99 (1) Children's Programmes: (a) Local comrnission巴:d programmes (2 page) (b) Overseas acquired prograImnes (8 pages) (2) Progr缸nmes for Young Persons (1 page) (3) Programmes for Senior Citizens/Elderly (a) Loω1 commissioned programmes (1 page) (b) Overseas acquired programmes (1 p在 ge) (4) Programmes for Arts and Culture Programmes (a) Local comrnissioned progr。但nmes (2 pages) (b) Overseas acquired programmes (1 page) ViuTV 96 (5) Childr凹 's Programmes (12 pages) Name and telephone number of the IName: Eva S Chan contact person for this retuffi. Signa仙re: Full Name Position in Licensee Company: General Manager, Regulatory Affairs and Compliance Date: 29 March 2019 page: 1/16 Local commissioned - ViuτV - Channel 99 (Year 2018) Arts & Culture program Age Broadcast programme Title Production Source Formatl Nature Contentl Objective Target Schedule MADE IN HONG KONG 可 MADEIN Local NA Documenta叩 香港λ生活百貨依賴人口 -

Sarahi Diaz on Set Acting Coach

Sarahi Diaz On Set Acting Coach MEET SARAHI Sarahi Diaz is an Actress, an On Set Coach, a host and Emmy award-wining writer. Sarahi has worked in the entertainment industry for over 20 years and has worked in film, television, theater, commercials and written sketch comedy, for which she received an Emmy award in 2010. Sarahi always enjoyed teaching, so when the opportunity came for her to become an On Set Acting Coach for “Every Witch Way” on Nickelodeon, she took it. She also worked as On Set Coach for “Vikki RPM”, Nickelodeon’s “Toni La Chef”, “Talia in The Kitchen” and “WITS Academy”. Recently she has been more focused on acting workshops, private coaching to guide new talents on their acting journey & an acting teacher for Universal Academy & the Roxy Teatre. THE ACTOR INSIDE - WORKSHOPS & ONE ON ONE SESSION What sets Sarahi apart as an acting coach, writer and actress is that she always give one hundred percent & expect the same back. She understands how hard it is to succeed in this business and keep going giving it your best. She really gets results when it comes to her students booking parts whether it is on TV shows or Films. She offers a series of Acting Workshops that cover all levels, from the most basic to advanced acting. Workshops cover topics such as: • What Makes a Great Headshot • How to Make Your Self-Submission Unique • Selling Yourself in Under 60 Seconds • Character Development • Acting for Sitcoms • Learning to Slate Like a Pro • How to Breakdown a Script • How to Book a Network Show • Acting Do’s and Do Not’s • Improvisational Skills • Choosing a Monologue • Comedic Timing • Being Aware of the Camera • Voice Over As for the One on One sessions, Sarahi has helped talents with improve, cold reading techniques, script analysis, scene study, commercial techniques, monologue, individual evaluation & goal setting and most importantly preparing for auditions (Film, TV Show, Play, commercial, etc.) which sometimes include putting the audition on tape for submission. -

Nickelodeon Se Diferencia Con Más Producción Original

WWW.PRENSARIO.TV WWW.PRENSARIO.TV //// EDITORIAL POR NICOLÁS SMIRNOFF Natpe Miami + Kidscreen Este no es un Especial más de Kids & Teens contenidos terminados, producción, for- en PRENSARIO, que distribuimos dentro y por matos, inversiones, coproducciones, co- separado de la edición central de Natpe desarrollos, sinergias 360, etc. Su despegue Miami, durante el evento en el hotel Fon- no lleva tantos años, aún tiene mucho para tainebleau. También, el Especial por prime- dar. ra vez lo distribuimos como nuestra edición Del conjunto del mercado infanto juve- de Kidscreen, que se realiza en febrero en la nil… qué se puede decir? En esta columna misma Miami. suelo describir la evolución de mis hijos, ¿Qué le cambia al lector raso? Hay más dos varones — hoy 17 y 14 años— y una informes, más páginas, más presencia nena menor —11— a medida que crecen. de empresas de Kids & Teens con notas y sus consumos de contenidos, plataformas anuncios, y más desarrollo del sector en ge- y dispositivos. Hoy los tres, que hace un neral. En una primera vista no se ve tanto tiempo se habían alejado de la tele normal la diferencia, pero página a página estamos para dedicarse a juegos y videos sueltos en muy conformes con la superación de la edi- YouTube, han descubierto Netflix y ven ción. mucho películas y series on demand. Hay mucho interés en nuestro parque de Los dos más chicos coinciden en ver La anunciantes por Kidscreen. Ha ido crecien- Rosa de Guadalupe, la serie de Televisa que do año a año como el evento especializado refleja temáticas osadas —embarazos, en el target infanto juvenil, y tiene todos prostitución, etc. -

Viacom to Open State of the Art Production Studio in Miami

Viacom to Open State of the Art Production Studio in Miami Studio Will Serve As Multiplatform Production Hub NEW YORK & MIAMI--(BUSINESS WIRE)-- Viacom Inc. (NASDAQ: VIAB, VIA) announced today that it will open a two-stage, 88,000 square foot, state-of-the-art production facility in Miami, Florida. The new studio, which was built by the Miami Omni Community Redevelopment Agency (CRA) as a public-private partnership with EUE/Screen Gems Studios, will serve as a production hub for Viacom's global entertainment brands including Nickelodeon, MTV and Comedy Central. This Smart News Release features multimedia. View the full release here: http://www.businesswire.com/news/home/20151005006444/en/ "We are creating more content than ever before across all of our brands at Viacom," said Robert Bakish, President and CEO of Viacom International Media Networks (VIMN). "The Viacom International Studio in Miami will offer a turnkey facility where we can create even more original, high quality content to meet the increasing demand for long-and- short-form content on all of our global platforms." "We have had terrific success with the recent live action productions we have coming from Miami, and we are very excited to be committed to doing more," said Cyma Zarghami, President, Viacom Kids and Family Group. "We are constantly looking for new creative ideas and content formats that allow us to tell stories in a completely different way, and this facility will certainly forward that effort." View of the Viacom International Studio in Miami, Florida (Photo: Business Wire) "Viacom has demonstrated again and again that hits come from all over the world," said Pierluigi Gazzolo, President, VIMN Americas and Executive Vice President, Nickelodeon International. -

On Set Acting Coach for Nickelodeon/”Every Witch Way” Season #1 2012-2014 • “Talia’S in the Kitchen” Season #1 and #2 “WITS Academy”

• On Set Acting Coach for Nickelodeon/”Every Witch Way” season #1 2012-2014 • “Talia’s in the Kitchen” season #1 and #2 “WITS Academy” • Sarahi Diaz is a recipient of a 2010 Emmy award for writing on “El Vacilon” an “SNL”, type show where she wrote and performed her own sketches. • Her resume includes a laundry list of film, television and Theater that have reflected her talent in drama, comedy and in split second improvisation. • With appearances on Burn notice(USA networks) El Vacilon sketch comedy show, the Morning show-off finalist (CW Channel 31) Despierta America (Univision) Co-Hosted The Emmy Award-winning live late night television program, A oscuras Pero Encendidos were she mesmerized audiences with her Quick wit and charming persona., also Co-hosted Viva Tv (NBC),In & Out, El Buzz, Caliente(Telemundo), La Gran Audicion • She has appeared in numerous Indie films “Tony Tango,” Hitters anonymous( Steven Bauer, Linda Blair) It's tough being me, The Cellist, Connected, La Americanita, The Good Life, Tia Maria, El Revolver del Cabello Rojo) She is a member of Screen Actors Guild and AFTRA, and has enjoyed teaching throughout her career in different schools and seminars like Universal Academy and “Blue Dog” school of Acting for children. And has also appeared in numerous National commercials (Visa, State Farm, McDonald's, At&t, Coca Cola, Crest, Royal Caribbean, Publix, Finger Hut ), • She has appeared in numerous National commercials (Visa, State Farm, McDonald's, At&t, Coca Cola, Crest, Royal Caribbean, Publix, FingerHut ), Indie films ( Hitters anonymous( Steven Bauer, Linda Blair) It's tough being me, The Cellist, Connected, La Americanita, The Good Life, Tia Maria, El Revolver del Cabello Rojo) . -

Ad Pages Template

IMPERSONATING ELVIS SINCE 1992 COVER DESIGN BY ROBERT MAESTAS | DOODLES BY TAMARA SUTTON VOLUME 24 | ISSUE 42 | OCTOBER 15-21, 2015 | FREE [2] WEEKLY ALIBI OCTOBER 15-21 , 2015 OCTOBER 15-21 , 2015 WEEKLY ALIBI [3] alibi VOLUME 24 | ISSUE 42 | OCTOBER 15-21 , 2015 EDITORIAL FILM EDITOR: Devin D. O’Leary (ext. 230) [email protected] MUSIC EDITOR : August March (ext. 245) [email protected] FOOD EDITOR/MANAGING EDITOR : Ty Bannerman (ext. 260) [email protected] CALENDARS EDITOR/COPY EDITOR: Renee Chavez (ext. 255) [email protected] STAFF WRITER: Maggie Grimason (ext. 239) [email protected] EDITORIAL INTERN : Megan Reneau [email protected] Cerridwen Stucky [email protected] CONTRIBUTING WRITERS: Cecil Adams, Sam Adams, Steven Robert Allen, Gustavo Arellano, Rob Brezsny, Shawna Brown, Suzanne Buck, Eric Castillo, David Correia, Mark Fischer, Ari LeVaux, Mark Lopez, August March, Genevieve Mueller, Geoffrey Plant, Benjamin Radford, Jeremy Shattuck, Holly von Winckel PRODUCTION ART DIRECTOR/PRODUCTION MANAGER : Archie Archuleta (ext. 240) [email protected] EDITORIAL DESIGNER/ILLUSTRATOR : Robert Maestas (ext.256) [email protected] ILLUSTRATOR/GRAPHIC DESIGNER : Tamara Sutton (ext.254) [email protected] STAFF PHOTOGRAPHER: Eric Williams [email protected] CONTRIBUTING ARTISTS: Ben Adams, Eva Avenue, Cutty Bage, Max Cannon, Michael Ellis, Adam Hansen, Jodie Herrera, KAZ, Jack Larson, Tom Nayder, Ryan North SALES SALES DIRECTOR: Sarah Bonneau (ext. 235) [email protected] SENIOR DISPLAY ACCOUNT EXECUTIVE: John Hankinson (ext. 265) [email protected] ACCOUNT EXECUTIVES: Rudy Carrillo (ext. 245) [email protected] Valerie Hollingsworth (ext. 263) [email protected] Sally Jackson (ext. 264) [email protected] Dawn Lytle (ext. 258) [email protected] Tierna Unruh-Enos (ext. -

Nickelodeon Showcases Power of Its Ecosystem and Highlights New Content Slate and Upcoming Initiatives for 2015-2016 Season at Annual Upfront Presentation

Nickelodeon Showcases Power of Its Ecosystem and Highlights New Content Slate and Upcoming Initiatives for 2015-2016 Season at Annual Upfront Presentation Nickelodeon Unveils Noggin—New Preschool Subscription Service; Previews Innovative, New Content Initiatives; Announces More Than 600 Episodes of New and Returning Series Nick Brands Its Partnership Marketing Services Under New Banner of Nickelodeon Inside Out Solutions NEW YORK--(BUSINESS WIRE)-- Nickelodeon, at its annual upfront presentation held today at the Skylight at Moynihan Station, outlined the power of its unmatched, 10-screen ecosystem to deliver the biggest and most engaged audience of kids and families, and announced numerous key initiatives from its content pipeline. The new series and development projects underscore Nick's commitment to fresh and innovative formats, from a wide range of creative sources and voices. Announcements at the presentation included: Noggin, a mobile subscription service for preschoolers; numerous new content innovations; a sneak peek at a potential SpongeBob SquarePants Broadway musical; future spinoff possibilities for the wildly successful Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles franchise; and Nickelodeon Sports, which brings content from the major sports leagues to Nick's platforms. Nickelodeon also detailed the suite of its partner services that provides consumer insights, advertising solutions and branded-entertainment opportunities, now formalized under the banner of Nickelodeon Inside Out Solutions. The presentation was augmented by an appearance from Will Arnett--star of Paramount Pictures' global theatrical hit, Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles, and the forthcoming sequel set for 2016; a performance of a song from the SpongeBob SquarePants musical, currently being developed for a potential Broadway Pictured: (L-R) Cesar Millan, Calvin Millan and Stuff in Mutt & Stuff, a new live-action preschool series coming to Nickelodeon in the 2015-16 season. -

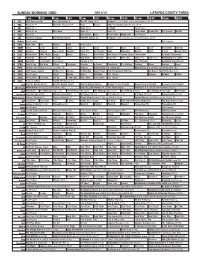

Sunday Morning Grid 10/11/15 Latimes.Com/Tv Times

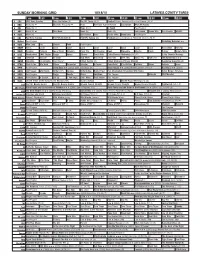

SUNDAY MORNING GRID 10/11/15 LATIMES.COM/TV TIMES 7 am 7:30 8 am 8:30 9 am 9:30 10 am 10:30 11 am 11:30 12 pm 12:30 2 CBS CBS News Sunday Face the Nation (N) The NFL Today (N) Å Football St. Louis Rams at Green Bay Packers. (N) Å 4 NBC News (N) Å Meet the Press (N) Å News Rescue 2015 Presidents Cup Final Day. (N) Å 5 CW News (N) Å News (N) Å In Touch Paid Program 7 ABC News (N) Å This Week News (N) News (N) Jack Hanna Ocean Mys. Sea Rescue Wildlife 9 KCAL News (N) Joel Osteen Hour Pastor Mike Woodlands Paid Program 11 FOX Fox News Sunday FOX NFL Kickoff (N) FOX NFL Sunday (N) Football Seattle Seahawks at Cincinnati Bengals. (N) Å 13 MyNet Paid Program Paid Program 18 KSCI Man Land Paid Church Faith Paid Program 22 KWHY Cosas Local Local Local Local Local Local Local Local Local RescueBot Transfor. 24 KVCR Painting Painting Joy of Paint Wyland’s Paint This Oil Painting Cook Moveable Martha Pépin Baking Simply Ming 28 KCET Wunderkind 1001 Nights Raggs Space Edisons Travel-Kids Rick Steves’ Dynamic Europe: Amsterdam Ed Slott’s Retirement 30 ION Jeremiah Youssef In Touch Bob Show Bob Show Dive, Olly Dive, Olly Doki (TVY) Doki (TVY7) Waterworld ›› (1995) 34 KMEX Conexión En contacto Paid Program Planeta U (TVY) Sal y Pimienta República Deportiva (N) 40 KTBN Walk in the Win Walk Prince Carpenter Schuller In Touch PowerPoint It Is Written Pathway Super Kelinda Jesse 46 KFTR Formula One Racing Russian Grand Prix. -

Florida Casting Credits

Lori S. Wyman, C.S.A. Lori Wyman Casting 16499 NE 19 Ave #203 N. Miami Beach, FL 33162 (305) 354-3901 [email protected] FLORIDA CASTING CREDITS TELEVISION: Bloodline (2015 Artios Award Nominee) Netflix - TV Series (Season 1-2) Ballers HBO - TV Pilot + TV series (Season 1-2) Documentary Now! IFC - TV Series (Ep: ‘Juan Loves Rice and Chicken’) Rosewood Fox Television – TV Pilot Hoke FX - TV Pilot The Arrangement USA Network - TV Pilot Graceland USA Network - TV Series Magic City Starz - TV Series The Glades A&E - TV Series (Season 1-4) Every Witch Way Nickelodeon - TV Series Talia in the Kitchen Nickelodeon - TV Series W.I.T.S. Academy Nickelodeon - TV Series Burn Notice Fox – Television Pilot + Episodes (Season 4-7) Dexter - (2007 Artios Award Nominee) Showtime - Television Pilot + FL Episodes CSI : MIAMI CBS - FL Episodes Havana Nocturne - Arturo Sandoval Story HBO Original Pictures S-Club 7 Initial - BBC ER Warner Bros. Television - FL Episode Homicide: Life on the Street Northern Entertainment - FL Episode Sins of the City ScreenVentures I/USA Network Maximum Bob Warner Bros/ABC Television Creature (ABC Miniseries) MGMWorldwideTelevision/TrilogyEntertainment Group Lawless Columbia/Tristar - TV Series Automatic Avenue 20th Century Fox Television – Television Pilot Sudden Terror...The Miami School Bus Hijacking Columbia/TriStar Television - MOW Pier 66 Spelling Entertainment - Television Pilot Keys ABC Television - Television Pilot Moon Over Miami Columbia Pictures Television –TV Series Triumph Over Disaster: The Hurricane Andrew Story NBC Productions - MOW Key West Viacom - Fox - Television Pilot America's Most Wanted Americas Most Wanted Productions – FL Episodes Mission of the Shark Fries Entertainment - MOW Wiseguy (Winner, 1990 Florida Crystal Reel Award - Best Casting) Cannell Films, Ltd. -

Sunday Morning Grid 10/18/15 Latimes.Com/Tv Times

SUNDAY MORNING GRID 10/18/15 LATIMES.COM/TV TIMES 7 am 7:30 8 am 8:30 9 am 9:30 10 am 10:30 11 am 11:30 12 pm 12:30 2 CBS CBS News Sunday Face the Nation (N) The NFL Today (N) Å Football Denver Broncos at Cleveland Browns. (N) Å 4 NBC News (N) Å Meet the Press (N) Å News PGA Tour Year in Review Countdown NASCAR Racing 5 CW News (N) Å News (N) Å In Touch Paid Program 7 ABC News (N) Å This Week News (N) News (N) Jack Hanna Ocean Mys. Sea Rescue Wildlife 9 KCAL News (N) Joel Osteen Hour Pastor Mike Woodlands Paid Program 11 FOX Fox News Sunday FOX NFL Kickoff (N) FOX NFL Sunday (N) Football Arizona Cardinals at Pittsburgh Steelers. (N) Å 13 MyNet Paid Program Disturbing Behavior ›› 18 KSCI Man Land Paid Church Faith Paid Program 22 KWHY Cosas Local Local Local Local Local Local Local Local Local RescueBot Transfor. 24 KVCR Painting Painting Joy of Paint Wyland’s Paint This Oil Painting Cook Moveable Martha Pépin Baking Simply Ming 28 KCET Wunderkind 1001 Nights Raggs Space Edisons Travel-Kids Celtic Thunder Mythology (TVG) Å Celtic Thunder Heritage 30 ION Jeremiah Youssef In Touch Bob Show Bob Show Dive, Olly Dive, Olly Doki (TVY) Doki (TVY) The Karate Kid ››› 34 KMEX Conexión En contacto Paid Program Fútbol Central (N) Fútbol Mexicano Primera División República Deportiva (N) 40 KTBN Walk in the Win Walk Prince Carpenter Schuller In Touch PowerPoint It Is Written Pathway Super Kelinda Jesse 46 KFTR Paid Program Snow Dogs ›› (2002) Cuba Gooding Jr.