YANKEE POST ANTHONY ROY, President March, 2021 TIM WEINLAND DAN COUGHLIN, Co-Editors

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Transmittal Email to House and Senate Members

Sent: Monday, March 5, 2018 1:47 PM To: David Ainsworth; Robert Bancroft; John Bartholomew; Fred Baser; Lynn Batchelor; Scott Beck; Paul Belaski; Steve Beyor; Clem Bissonnette; Thomas Bock; Bill Botzow; Patrick Brennan; Tim Briglin; Cynthia Browning; Jessica Brumsted; Susan Buckholz; Tom Burditt; Mollie Burke; William Canfield; Stephen Carr; Robin Chesnut-Tangerman; Annmarie Christensen; Kevin Christie; Brian Cina; Selene Colburn; Jim Condon; Peter Conlon; Daniel Connor; Chip Conquest; Sarah CopelandHanzas; Timothy Corcoran; Larry Cupoli; Maureen Dakin; David Deen; Dennis Devereux; Eileen Dickinson; Anne Donahue; Johannah Donovan; Betsy Dunn; Alyson Eastman; Alice Emmons; Peter Fagan; Rachael Fields; Robert Forguites; Robert Frenier; Douglas Gage; Marianna Gamache; John Gannon; Marcia Gardner; Dylan Giambatista; Diana Gonzalez; Maxine Grad; Rodney Graham; Adam Greshin; Sandy Haas; James Harrison; Mike Hebert; Robert Helm; Mark Higley; Matthew Hill; Mary Hooper; Jay Hooper; Lori Houghton; Mary Howard; Ronald Hubert; Kimberly Jessup; Ben Jickling; Mitzi Johnson; Ben Joseph; Bernie Juskiewicz; Brian Keefe; Kathleen Keenan; Charlie Kimbell; Warren Kitzmiller; Jill Krowinski; Rob LaClair; Martin LaLonde; Diane Lanpher; Richard Lawrence; Paul Lefebvre; Patti Lewis; William Lippert; Emily Long; Gabrielle Lucke; Terence Macaig; Michael Marcotte; Marcia Martel; Jim Masland; Christopher Mattos; Curt McCormack; Patricia McCoy; Francis McFaun; Alice Miller; Kiah Morris; Mary Morrissey; Mike Mrowicki; Barbara Murphy; Linda Myers; Gary Nolan; Terry -

2018 New Member Orientation November 26 – 27, 2018

2018 New Member Orientation November 26 – 27, 2018 Monday, November 26, 2018 *All events are in the State House unless noted* Throughout the day Slide Show: The Legislature Cafeteria Lounge 7:15 a.m. – 9:00 a.m. Registration, Payroll, Expenses, Benefits, Photographs, and Room: 10/Room: 11 iPad Distribution and Training 7:30 a.m. – 10:00 a.m. Breakfast [PLEASE register first] Cafeteria - sidebar Open Cafeteria Account (if desired) 9:15 a.m. – 9:25 a.m. Welcome and Introduction Room 11 Mark Snelling, President, Snelling Center for Government 9:25 a.m. – 10:10 a.m. The Legislative Process Senate Chamber, or New House and Senate Members go to their respective chambers House Chamber to discuss parliamentary procedures, reporting and debate of bills, the amendment process, recording and notice of proceedings in Calendars and Journals, and legislative decorum John Bloomer, Secretary of the Senate William MaGill, Clerk of the House 10:10 a.m. – 10:20 a.m. Transition to Room 11 on 1st Floor 10:20 a.m. – 10:50 a.m. Overview of the Office of Legislative Council Room 11 Luke Martland, Director and Chief Legislative Counsel 10:50 a.m. – 12:20 p.m. Drafting Bills, Committee Hearings, and the Role of Location to be determined Legislative Council Discussion of the drafting process, bill introduction, the legislative committee process, and the role of the Office VT LEG #319211 v.1A 2018 New Member Orientation Page 2 of 6 Monday, November 26, 2018 continued 12:20 p.m. – 12:30 p.m. Transition to State House Cafeteria on 2nd floor 12:30 p.m. -

Senate Standing Committees 2017 Govt

Senate Standing Committees 2017 Govt. Operations Sen. Jeanette White, Chair Agriculture Sen. Brian Collamore, V-Chair Sen. Bobby Starr, Chair Sen. Claire Ayer Sen. Anthony Pollina, V-Chair Sen. Alison Clarkson Sen. Brian Collamore Sen. Chris Pearson Sen. Carolyn Branagan Sen. Francis Brooks Health and Welfare Sen. Claire Ayer, Chair Appropriations Sen. Virginia Lyons, V-Chair Sen. Jane Kitchel, Chair Sen. Anne Cummings Sen. Alice Nitka, V-Chair Sen. Dick McCormack Sen. Richard Sears Sen. Debra Ingram Sen. Bobby Starr Sen. Dick McCormack Institutions Sen. Tim Ashe Sen. Peg Flory, Chair Sen. Richie Westman Sen. John Rogers, V-Chair Sen. Dick Mazza Econ Dev, Housing, and General Affairs Sen. Carolyn Branagan Sen. Kevin Mullin, Chair Sen. Francis Brooks Sen. Michael Sirotkin, V-Chair Sen. Philip Baruth Judiciary Sen. Becca Balint Sen. Dick Sears, Chair Sen. Alison Clarkson Sen. Joe Benning, V-Chair Sen. Jeanette White Education Sen. Alice Nitka Sen. Philip Baruth, Chair Sen. Tim Ashe Sen. Becca Balint, V-Chair Sen. Kevin Mullin Natural Resources Sen. Joe Benning Sen. Chris Bray, Chair Sen. Chris Bray Sen. Brian Campion, V-Chair Sen. Debra Ingram Sen. Mark MacDonald Sen. John Rogers Finance Sen. Chris Pearson Sen. Anne Cummings, Chair Sen. Mark MacDonald, V-Chair Transportation Sen. Virginia Lyons Sen. Dick Mazza, Chair Sen. Anthony Pollina Sen. Richie Westman, V-Chair Sen. Michael Sirotkin Sen. Jane Kitchel Sen. Brian Campion Sen. Peg Flory Sen. Dustin Degree Sen. Dustin Degree . -

Refer to This List for Area Legislators and Candidates

CURRENT LEGISLATORS Name District Role Email Daytime Phone Evening Phone Sen. Richard Westman Lamoille County [email protected] Rep. Dan Noyes Lamoille-2 [email protected] (802) 730-7171 (802) 644-2297 Speaker Mitzi Johnson Grand Isle-Chittenden Speaker of the House [email protected] (802) 363-4448 Sen. Tim Ashe Chittenden County Senate President [email protected] (802) 318-0903 Rep. Kitty Toll Caledona-Washington Chair, House Appropriations Committee [email protected] Sen. Jane Kitchel Caledonia County Chair, Senate Appropriations Committee [email protected] (802) 684-3482 Rep. Mary Hooper Washington-4 Vice Chair, House Appropriations Committee [email protected] (802) 793-9512 Rep. Marty Feltus Caledonia-4 Member, House Appropriations Committee [email protected] (802) 626-9516 Rep. Patrick Seymour Caledonia-4 [email protected] (802) 274-5000 Sen. Joe Benning Caledonia County [email protected] (802) 626-3600 (802) 274-1346 Rep. Matt Hill Lamoille 2 *NOT RUNNING IN 2020 [email protected] Sen. Phil Baruth Chittenden County Chair, Senate Education Committee [email protected] (802) 503-5266 Sen. Corey Parent Franklin County Member, Senate Education Committee [email protected] 802-370-0494 Sen. Randy Brock Franklin County [email protected] Rep. Kate Webb Chittenden 5-1 Chair, House Education Committee [email protected] (802) 233-7798 Rep. Dylan Giambatista Chittenden 8-2 House Leadership/Education Committee [email protected] (802) 734-8841 Sen. Bobby Starr Essex-Orleans Member, Senate Appropriations Committee [email protected] (802) 988-2877 (802) 309-3354 Sen. -

HOUSE COMMITTEES 2019 - 2020 Legislative Session

HOUSE COMMITTEES 2019 - 2020 Legislative Session Agriculture & Forestry Education Health Care Rep. Carolyn W. Partridge, Chair Rep. Kathryn Webb, Chair Rep. William J. Lippert Jr., Chair Rep. Rodney Graham, Vice Chair Rep. Lawrence Cupoli, Vice Chair Rep. Anne B. Donahue, Vice Chair Rep. John L. Bartholomew, Ranking Mbr Rep. Peter Conlon, Ranking Member Rep. Lori Houghton, Ranking Member Rep. Thomas Bock Rep. Sarita Austin Rep. Annmarie Christensen Rep. Charen Fegard Rep. Lynn Batchelor Rep. Brian Cina Rep. Terry Norris Rep. Caleb Elder Rep. Mari Cordes Rep. John O'Brien Rep. Dylan Giambatista Rep. David Durfee Rep. Vicki Strong Rep. Kathleen James Rep. Benjamin Jickling Rep. Philip Jay Hooper Rep. Woodman Page Appropriations Rep. Christopher Mattos Rep. Lucy Rogers Rep. Catherine Toll, Chair Rep. Casey Toof Rep. Brian Smith Rep. Mary S. Hooper, Vice Chair Rep. Peter J. Fagan, Ranking Member Energy & Technology Human Services Rep. Charles Conquest Rep. Timothy Briglin, Chair Rep. Ann Pugh, Chair Rep. Martha Feltus Rep. Laura Sibilia, Vice Chair Rep. Sandy Haas, Vice Chair Rep. Robert Helm Rep. Robin Chesnut-Tangerman, Rep. Francis McFaun, Ranking Member Rep. Diane Lanpher Ranking Member Rep. Jessica Brumsted Rep. Linda K. Myers Rep. R. Scott Campbell Rep. James Gregoire Rep. Maida Townsend Rep. Seth Chase Rep. Logan Nicoll Rep. Matthew Trieber Rep. Mark Higley Rep. Daniel Noyes Rep. David Yacovone Rep. Avram Patt Rep. Kelly Pajala Rep. Heidi E. Scheuermann Rep. Marybeth Redmond Commerce & Rep. Michael Yantachka Rep. Carl Rosenquist Rep. Theresa Wood Economic Development General, Housing, & Military Affairs Rep. Michael Marcotte, Chair Judiciary Rep. Thomas Stevens, Chair Rep. Jean O'Sullivan, Vice Chair Rep. -

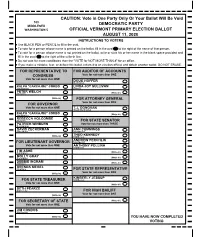

Ballot Paper

CAUTION: Vote in One Party Only Or Your Ballot Will Be Void 103 DEMOCRATIC PARTY MIDDLESEX WASHINGTON 5 OFFICIAL VERMONT PRIMARY ELECTION BALLOT AUGUST 11, 2020 INSTRUCTIONS TO VOTERS Use BLACK PEN or PENCIL to fill in the oval. To vote for a person whose name is printed on the ballot, fill in the oval to the right of the name of that person. To vote for a person whose name is not printed on the ballot, write or stick his or her name in the blank space provided and fill in the oval to the right of the write-in line. Do not vote for more candidates than the "VOTE for NOT MORE THAN #" for an office. If you make a mistake, tear, or deface the ballot, return it to an election official and obtain another ballot. DO NOT ERASE. FOR REPRESENTATIVE TO FOR AUDITOR OF ACCOUNTS CONGRESS Vote for not more than ONE Vote for not more than ONE DOUG HOFFER Burlington RALPH "CARCAJOU" CORBO LINDA JOY SULLIVAN Wallingford Dorset PETER WELCH Norwich (Write-in) (Write-in) FOR ATTORNEY GENERAL Vote for not more than ONE FOR GOVERNOR Vote for not more than ONE T.J. DONOVAN South Burlington RALPH "CARCAJOU" CORBO Wallingford (Write-in) REBECCA HOLCOMBE Norwich FOR STATE SENATOR PATRICK WINBURN Vote for not more than THREE Bennington DAVID ZUCKERMAN ANN CUMMINGS Hinesburg Montpelier THEO KENNEDY (Write-in) Middlesex ANDREW PERCHLIK FOR LIEUTENANT GOVERNOR Montpelier Vote for not more than ONE ANTHONY POLLINA Middlesex TIM ASHE Burlington (Write-in) MOLLY GRAY Burlington (Write-in) DEBBIE INGRAM Williston (Write-in) BRENDA SIEGEL Newfane FOR STATE REPRESENTATIVE Vote for not more than ONE (Write-in) KIMBERLY JESSUP FOR STATE TREASURER Middlesex Vote for not more than ONE (Write-in) BETH PEARCE Barre City FOR HIGH BAILIFF Vote for not more than ONE (Write-in) FOR SECRETARY OF STATE (Write-in) Vote for not more than ONE JIM CONDOS Montpelier (Write-in) YOU HAVE NOW COMPLETED VOTING . -

Bi-State Primary Care Association, January 2020

Vermont 2020January 2020 Primary Care Sourcebook Bi-State Primary Care Association 61 Elm Street, Montpelier, Vermont 05602 (802) 229-0002 www.bistatepca.org TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction to Bi-State Page 3 Overcoming Transpiration Barriers Page 18 Bi-State PCA Vermont Members Page 4 Helping Patients Experiencing Homelessness Page 19 Key Elements of Bi-State’s Work Page 5 Accessing Nutritious Food Page 19 FQHC’s, AHEC, PPNNE, and VCCU Page 7 Reducing Isolation for Farmworkers Page 20 Member Map Page 8 Other Elements of Comprehensive Care Page 21 Payer Mix Page 9 Vermont Rural Health Alliance (VRHA) Page 24 Bi-States 2019-2020 Vermont Public Policy 1 in 3 Vermonters in over 88 Sites Page 10 Page 27 Principles Investing in Primary Care Page 11 FQHC Funding Page 28 Workforce Development Supports Primary Care Page 13 FQHC and ACO Participation Page 28 Bi-State Workforce Recruitment Center Page 14 FQHC Federal Requirements Page 29 Workforce & Area Health Education Centers (AHEC) Page 15 Member Sites by Organization Page 30 Addressing All the Factors of Wellness Page 17 Member Sites by County Page 31 Legislative Representation List Biennium 2019 – Tracking Social Determinants of Health Page 18 Page 33 2020 2 What is a Primary Care Association? Each of the 50 states (or in Bi-State’s case, a pair of states) has one nonprofit Primary Care Association (PCA) to serve as the voice for Community Health Centers. These health centers were born out of the civil rights and social justice movements of the 1960’s with a clear mission that prevails today: to provide health care to communities with a scarcity of providers and services. -

Meet Dean Corren Anti-Union 'Think Tank' Wrong About Vermont

Meet Dean Corren Dean Corren talks to board of directors recently. When your board of directors voted single payer health care.” ourselves,” he said in a recent interview to recommend Dean Corren for at Vermont-NEA headquarters. “If Corren, a Progressive who also has the lieutenant governor, the decision we are going to have a functioning backing of Democrats, wants to be a was easy. democracy, we need to restore the lieutenant governor who “will work to meaning of politics.” “He really gets it,” President Martha restore the meaning of politics.” By that, Allen said. “Dean is an unabashed he wants to transform “politics” from This is not Corren’s first stab at elected union supporter. He is a believer in angry, partisan wrangling to a platform office. He served four terms in the the importance of public education. where people of differing views House from 1993-2000; he also was And he, alone among all of the exchange ideas, debate, and agree on an aide to then-Congressman Bernie statewide candidates out there, is a course of action that serves only one Sanders. For more than a decade, dedicated to ensuring our members purpose: to better the lives of everyone. he’s been the chief technology officer are treated fairly in the transition to “Politics, at its core, is how we govern continued on p. 7 Vol. 81 No. 2 • Oct., 2013 www.vtnea.orgThe Official Publication of the Vermont-National EducationAssociation Anti-Union ‘Think Tank’ Wrong About Vermont Vermont-NEA Vermont-NEA Editor’s Note: Vermont-NEA President course let alone reality. -

General Election Results

U.S. Senator Candidate TOTAL Percent Len Britton (Pomfret) - Republican 200 22% Stephen J. Cain ( Burlington) - Independent 8 1% Pete Diamondstone (Brattleboro) - Socialist 0 0% Cris Ericson (Chester) - United States Marijuna 7 1% Daniel Freilich (Wilmington) - Independent 15 2% Patrick Leahy (Middlesex) - Democratic 627 70% Johenry Nunes (Isle LaMotte) - Independent 0 0% Write In: 0 0% Write In: 0 0% Write In: 0 0% Spoiled 1 0% Blank 36 4% TOTALS 896 100% Representative to Congress Candidate TOTAL Percent Paul D. Beaudry (Swanton) - Republican 211 24% Gus Jaccaci (Thetford) - Independent 21 2% Jane Newton (Londonderry) - Socialst 7 1% Peter Welch 625 70% Write In: Len Britton 1 0% Write In: 0 0% Spoiled 2 0% Blank 29 3% TOTALS 896 100% Governor Candidate TOTAL Percent Brian Dubie (Essex) - Republican 345 39% Cris Ericson (Chester) - Independent 4 0% Dan Feliciano (Essex) - Independent 6 1% Ben Mitchell (Westminster) - Liberty Union 1 0% Em Peyton (Putney) - Independent 3 0% Peter Shumlin (Putney) - Democratic/Working Families 517 58% Dennis Steele (Kirby) - Independent 9 1% Write In: Matt Dunn 2 0% Write In: Phil Scott 1 0% Write In: Doug Racine 2 0% Spoiled 1 0% Blank 5 1% TOTALS 896 100% Lieutenant Governor Candidate TOTAL Percent Peter Garritano (Shelburne) - Independent 28 3% Steve Howard (Rutland City) - Democratic 359 40% Marjorie Power (Montpelier) - Progressive 41 5% Phil Scott (Berlin) - Republican 416 46% Boots Wardinski (Newbury) - Liberty Union 5 1% Write In: 0 0% Spoiled 0 0% Blank 47 5% TOTALS 896 100% State Treasurer Candidate -

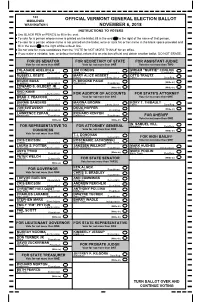

Ballot Paper

103 MIDDLESEX OFFICIAL VERMONT GENERAL ELECTION BALLOT WASHINGTON 5 NOVEMBER 6, 2018 INSTRUCTIONS TO VOTERS Use BLACK PEN or PENCIL to fill in the oval. To vote for a person whose name is printed on the ballot, fill in the oval to the right of the name of that person. To vote for a person whose name is not printed on the ballot, write or stick his or her name in the blank space provided and fill in the oval to the right of the write-in line. Do not vote for more candidates than the "VOTE for NOT MORE THAN #" for an office. If you make a mistake, tear, or deface the ballot, return it to an election official and obtain another ballot. DO NOT ERASE. FOR US SENATOR FOR SECRETARY OF STATE FOR ASSISTANT JUDGE Vote for not more than ONE Vote for not more than ONE Vote for not more than TWO FOLASADE ADELUOLA JIM CONDOS MIRIAM "MUFFIE" CONLON Shelburne Independent Montpelier Democratic Montpelier Democratic RUSSELL BESTE MARY ALICE HEBERT OTTO TRAUTZ Burlington Independent Putney Liberty Union Cabot Dem/Rep BRUCE BUSA H. BROOKE PAIGE Readsboro Independent Washington Republican (Write-in) EDWARD S. GILBERT JR Barre Town Independent (Write-in) (Write-in) REID KANE Hartford Liberty Union FOR AUDITOR OF ACCOUNTS FOR STATE'S ATTORNEY BRAD J. PEACOCK Vote for not more than ONE Vote for not more than ONE Shaftsbury Independent BERNIE SANDERS MARINA BROWN RORY T. THIBAULT Burlington Independent Charleston Liberty Union Cabot Dem/Rep JON SVITAVSKY DOUG HOFFER Bridport Independent Burlington Dem/Prog (Write-in) LAWRENCE ZUPAN RICHARD KENYON Manchester Republican Brattleboro Republican FOR SHERIFF Vote for not more than ONE (Write-in) (Write-in) W. -

MEMORANDUM To: Senator Jane Kitchel, Chair, Senate Committee

115 STATE STREET SEN. VIRGINIA "GINNY" LYONS, CHAIR MONTPELIER, VT 05633 SEN. RUTH HARDY, VICE CHAIR TEL: (802) 828-2228 SEN. JOSHUA TERENZINI, CLERK FAX: (802) 828-2424 SEN. ANN CUMMINGS SEN. CHERYL HOOKER STATE OF VERMONT GENERAL ASSEMBLY SENATE COMMITTEE ON HEALTH AND WELFARE MEMORANDUM To: Senator Jane Kitchel, Chair, Senate Committee on Appropriations From: Senator Ginny Lyons, Chair, Senate Committee on Health and Welfare Date: March 16, 2021 Subject: H.315 recommendations The Senate Committee on Health and Welfare has reviewed and taken testimony on H.315, An act relating to COVID-19 relief, as passed by the House, and we have several recommendations. We also want to identify additional areas of interest that we would like to continue to explore with the Senate Committee on Appropriations for potential inclusion in the FY22 budget bill. H.315 Recommendations Grants to Reach Up Participants The Committee on Health and Welfare supports appropriating $1.3 million to continue providing additional financial support to families participating in the Reach Up program, as proposed in H.315. We defer to the Committee on Appropriations in determining the proper source of funds for this appropriation. Purchase and Distribution of Diapers The Committee on Health and Welfare recommends appropriating $82,000 to the Department for Children and Families for a grant to the Vermont Food Bank to purchase and distribute diapers to Vermonters in need. Recovery Centers The Committee on Health and Welfare recommends appropriating $240,000 to the Department of Health for the recovery centers in the Vermont Recovery Center Network. This would work out to be a $20,000 grant to each of the 12 recovery centers to help address the increased demand for substance use disorder treatment services, and thus increased caseload, that these centers have experienced as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic. -

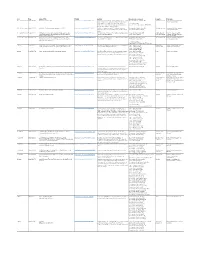

Civics Learning Act of 2021

State Name Summary/Title Weblink Analysis Sponsors and Co-Sponsors Committee Progression United States--Federal House Bill 400 Civics Learning Act of 2021. https://legiscan.com/US/text/HB400/2021 Authorizes Federal support for and gives grant preference to action Representative Alcee Hastings [D] Education and Labor Referred to the House Committee civics--"hands-on civic engagement activities," "before-school, on Education and Labor. during-school, after-school, and extracurricular activities," 50 co-sponsors [D]: "activities that include service learning and community service https://legiscan.com/US/sponsors/HB400/2021 projects that are linked to school curriculum," United States--Federal House Bill 1241 Full-Service Community School Expansion Act of 2021. https://legiscan.com/US/text/HB1241/2021 Authorizes "community partners," "family and community Representative Mondaire Jones [D] Education and Labor Referred to the House Committee engagement," and "real-world learning and community problem- Representative David Trone [D] on Education and Labor. solving." United States--Federal Senate Bill 879 A bill authorize the Secretary of Education to make grants to support https://legiscan.com/US/drafts/SB879/2021 The Civics Secures Democracy Act. Authorizes and funds action Senator Christopher Coons [D] Health, Education, Read twice and referred to the educational programs in civics and history, and for other purposes. civics. No bill text available yet. Senator John Cornyn [R] Labor, and Pensions Committee on Health, Education, [Duplicates House Bill 1814.] Labor, and Pensions. United States--Federal House Bill 1814 To authorize the Secretary of Education to make grants to support https://legiscan.com/US/drafts/HB1814/2021 The Civics Secures Democracy Act.