Choctawhatchee Bay

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Sedimentary Processes and Geomorphic History of Wreck Shoal, an Oyster Reef of the James River, Virginia

W&M ScholarWorks Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects 1986 THE SEDIMENTARY PROCESSES AND GEOMORPHIC HISTORY OF WRECK SHOAL, AN OYSTER REEF OF THE JAMES RIVER, VIRGINIA Joseph T. DeAlteris College of William and Mary - Virginia Institute of Marine Science Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wm.edu/etd Part of the Geology Commons Recommended Citation DeAlteris, Joseph T., "THE SEDIMENTARY PROCESSES AND GEOMORPHIC HISTORY OF WRECK SHOAL, AN OYSTER REEF OF THE JAMES RIVER, VIRGINIA" (1986). Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects. Paper 1539616626. https://dx.doi.org/doi:10.25773/v5-af3n-wf26 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects at W&M ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects by an authorized administrator of W&M ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. INFORMATION TO USERS While the most advanced technology has been used to photograph and reproduce this manuscript, the quality of the reproduction is heavily dependent upon the quality of the material submitted. For example: • Manuscript pages may have indistinct print. In such cases, the best available copy has been filmed. • Manuscripts may not always be complete. In such cases, a note will indicate that it is not possible to obtain missing pages. • Copyrighted material may have been removed from the manuscript. In such cases, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, and charts) are photographed by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand corner and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. -

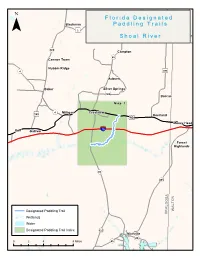

Florida Designated Paddling Trails Shoal River

F ll oCR)"r 6i0i2d a D e s ii g n a tt e d Blackman P a d d ll ii n g T r a ii ll s C)"R 2 ¯ )"2 C)"R 2 S h o a ll R ii v e r CR)" 147 189 «¬ Campton 85 Cannon Town «¬ Nubbin Ridge «¬4 )"393 Auburn Baker Silver Springs 188 )" Dorcas M a p 1 «¬4 Milligan Crestview )"189 Deerland ¤£90 Mossy Head 10 Holt Galliver ¨¦§ Forest Highlands «¬85 «¬285 A N S O O T O L L A A W Designated Paddling Trail K O Wetlands Water Designated Paddling Trail Index «¬123 Niceville «¬20 0 2 4 8 Miles «¬85 S h o a ll R ii v e rr P a d d ll ii n g T rr a ii ll M a p 1 )"188 STILLWELL BLVD ¯ NO B RTH AVE R V A A C L K L I N E Y S R T D F Crestview A I L R L C O H Y I L D D S 90 R T CH ¤£ D ES NU T A Þ VE !| 2)"80A Access Point 1: Ray Barnes Boat Ramp/US 90 N: 30.7535 W: -86.5099 OKALOOSA ¨¦§10 JOHN K ING RD L I 85 V ¬ E « O Okaloosa County Shoal River A K Land Acquisition PJ AD C AMS PKWY H U R C H R D A NT Choctawhatchee IOC Choctawhatchee H R Nat'l Forest D Nat'l Forest !|*IÞ Access Point 2: Bill Duggan Jr Park/SR 85 N: 30.6976 W: -86.5712 Shoal River Paddling Trail Eglin Air Force Base !| Canoe/Kayak Launch *I Restrooms Þ Potable Water Florida Conservation Lands 0 0.5 1 2 Miles Wetlands Shoal River Paddling Trail Guide The Waterway A nature photographer’s dream, the shallow, gold-tinted Shoal River threads through a northwest Florida wilderness of high sandy hills, broad sandbars perfect for rest stops, and floodplain forest. -

WALTON COUNTY LAND DEVELOPMENT CODE: CHAPTER 4 | Resource Protection Standards Revised September 10, 2019 Page 2 of 55

Revised September 10, 2019 Page 1 of 55 CHAPTER IV. RESOURCE PROTECTION STANDARDS 4.00.00. OVERALL PURPOSE AND INTENT The purpose of this chapter is to protect, conserve and enhance Walton County's natural and historical features. It is the intent of the County to enhance resource protection by utilizing development management techniques to control potential negative impacts from development and redevelopment on the resources addressed herein. Specifically, it is the intent of the County to limit the specific impacts and cumulative impacts of development or redevelopment upon historic sites, wetlands, coastal dune lakes, coastal dune lines, water quality, water quantity, wildlife habitats, living marine resources, or other natural resources through the use of site design techniques, such as clustering, elevation on pilings, setbacks, and buffering. The intent of this policy is to avoid such impact and to permit mitigation of impacts only as a last resort. 4.00.01. Permits Required. A. Local Development Order. Unless exempt under Section 1.15.00, a development order is required for all development or redevelopment of real property within the County. As a part of the application process defined in Chapter 1 of this Code, a landowner or developer must apply the provisions of this chapter before any other design work is done for any proposed land development. Application of the provisions of this chapter will divide a proposed development site into zones or areas that may be developed with minimal regulation, zones that may be developed under more stringent regulation and zones that must generally be left free of development activity. -

Sandbridge Beach FONSI

FINDING OF NO SIGNIFICANT IMPACT Issuance of a Negotiated Agreement for Use of Outer Continental Shelf Sand from Sandbridge Shoal in the Sandbridge Beach Erosion Control and Hurricane Protection Project Virginia Beach, Virginia Pursuant to the National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA), Council on Environmental Quality regulations implementing NEPA (40 CFR 1500-1508) and Department of the Interior (DOI) regulations implementing NEPA (43 CFR 46), the Bureau of Ocean Energy Management (BOEM) prepared an environmental assessment (EA) to determine whether the issuance of a negotiated agreement for the use of Outer Continental Shelf (OCS) sand from Sandbridge Shoal Borrow Areas A and B for the Sandbridge Beach Erosion Control and Hurricane Protection Project near Virginia Beach, VA would have a significant effect on the human environment and whether an environmental impact statement (EIS) should be prepared. Several NEPA documents evaluating impacts of the project have been previously prepared by both the US Army Corps of Engineers (USACE) and BOEM. The USACE described the affected environment, evaluated potential environmental impacts (initial construction and nourishment events), and considered alternatives to the proposed action in a 2009 EA. This EA was subsequently updated and adopted by BOEM in 2012 in association with the most recent 2013 Sandbridge nourishment effort (BOEM 2012). Prior to this, BOEM (previously Minerals Management Service [MMS]) was a cooperating agency on several EAs for previous projects (MMS 1997; MMS 2001; MMS 2006). This current EA, prepared by BOEM, supplements and summarizes the aforementioned 2012 analysis. BOEM has reviewed all prior analyses, supplemented additional information as needed, and determined that the potential impacts of the current proposed action have been adequately addressed. -

Geological Survey of Alabama Biological

GEOLOGICAL SURVEY OF ALABAMA Berry H. (Nick) Tew, Jr. State Geologist ECOSYSTEMS INVESTIGATIONS PROGRAM BIOLOGICAL ASSESSMENT OF THE LITTLE CHOCTAWHATCHEE RIVER WATERSHED IN ALABAMA OPEN-FILE REPORT 1105 by Patrick E. O'Neil and Thomas E. Shepard Prepared in cooperation with the Choctawhatchee, Pea and Yellow Rivers Watershed Management Authority Tuscaloosa, Alabama 2011 TABLE OF CONTENTS Abstract ............................................................ 1 Introduction.......................................................... 1 Acknowledgments .................................................... 3 Study area .......................................................... 3 Methods ............................................................ 3 IBI sample collection ............................................. 3 Habitat measures................................................ 8 Habitat metrics ............................................ 9 IBI metrics and scoring criteria..................................... 12 Results and discussion................................................ 17 Sampling sites and collection results . 17 Relationships between habitat and biological condition . 28 Conclusions ........................................................ 31 References cited..................................................... 33 LIST OF TABLES Table 1. Habitat evaluation form......................................... 10 Table 2. Fish community sampling sites in the Little Choctawhatchee River watershed ................................................... -

Short Creek and Shoal Creek in the Spring River Watershed Water Quality Impairment: Total Phosphorus

NEOSHO BASIN TOTAL MAXIMUM DAILY LOAD Waterbody / Assessment Unit: Short Creek and Shoal Creek in the Spring River Watershed Water Quality Impairment: Total Phosphorus 1.0 INTRODUCTION AND PROBLEM IDENTIFICATION Subbasin: Spring Counties: Cherokee HUC8: 11070207 HUC10(12): 08(06) & 09(04) Ecoregion: Ozark Highlands, Springfield Plateau (39a) Drainage Area: Shoal Creek = approximately 10.1 square miles in Kansas Short Creek = approximately 5.94 square miles in Kansas Water Quality Limited Segments Covered Under this TMDL: Station Main Stem Segment Tributary Station SC570 Short Creek (881) Station SC212 Shoal Creek (2) Unnamed Stream (886) 2008, 2010, 2012 & 2014 303(d) Listings: Kansas Stream segments monitored by stations SC212 on Short Creek and SC570 on Shoal Creek, are cited as impaired by Total Phosphorus (TP) for the Neosho Basin. Impaired Use: Special Aquatic Life, Expected Aquatic Life, Contact Recreation and Domestic Water Supply. Water Quality Criteria: Nutrients – Narratives: The introduction of plant nutrient into surface waters designated for domestic water supply use shall be controlled to prevent interference with the production of drinking water (K.A.R. 28-16-28e(c)(3)(D)). The introduction of plant nutrients into streams, lakes, or wetlands from artificial sources shall be controlled to prevent the accelerated succession or replacement of aquatic biota or the production of undesirable quantities or kinds of aquatic life (K.A.R. 28-16- 28e(c)(2)(A)). The introduction of plant nutrients into surface waters designated for primary or secondary contact recreational use shall be controlled to prevent the development of objectionable concentrations of algae or algal by-products or nuisance growths of submersed, floating, or emergent aquatic vegetation (K.A.R. -

Understanding the Temporal Dynamics of the Wandering Renous River, New Brunswick, Canada

Earth Surface Processes and Landforms EarthTemporal Surf. dynamicsProcess. Landforms of a wandering 30, 1227–1250 river (2005) 1227 Published online 23 June 2005 in Wiley InterScience (www.interscience.wiley.com). DOI: 10.1002/esp.1196 Understanding the temporal dynamics of the wandering Renous River, New Brunswick, Canada Leif M. Burge1* and Michel F. Lapointe2 1 Department of Geography and Program in Planning, University of Toronto, 100 St. George Street, Toronto, Ontario, M5S 3G3, Canada 2 Department of Geography McGill University, 805 Sherbrooke Street West, Montreal, Quebec, H3A 2K6, Canada *Correspondence to: L. M. Burge, Abstract Department of Geography and Program in Planning, University Wandering rivers are composed of individual anabranches surrounding semi-permanent of Toronto, 100 St. George St., islands, linked by single channel reaches. Wandering rivers are important because they Toronto, M5S 3G3, Canada. provide habitat complexity for aquatic organisms, including salmonids. An anabranch cycle E-mail: [email protected] model was developed from previous literature and field observations to illustrate how anabranches within the wandering pattern change from single to multiple channels and vice versa over a number of decades. The model was used to investigate the temporal dynamics of a wandering river through historical case studies and channel characteristics from field data. The wandering Renous River, New Brunswick, was mapped from aerial photographs (1945, 1965, 1983 and 1999) to determine river pattern statistics and for historical analysis of case studies. Five case studies consisting of a stable single channel, newly formed anabranches, anabranches gaining stability following creation, stable anabranches, and an abandoning anabranch were investigated in detail. -

Turkey Point Units 6 & 7 COLA

Turkey Point Units 6 & 7 COL Application Part 2 — FSAR SUBSECTION 2.4.1: HYDROLOGIC DESCRIPTION TABLE OF CONTENTS 2.4 HYDROLOGIC ENGINEERING ..................................................................2.4.1-1 2.4.1 HYDROLOGIC DESCRIPTION ............................................................2.4.1-1 2.4.1.1 Site and Facilities .....................................................................2.4.1-1 2.4.1.2 Hydrosphere .............................................................................2.4.1-3 2.4.1.3 References .............................................................................2.4.1-12 2.4.1-i Revision 6 Turkey Point Units 6 & 7 COL Application Part 2 — FSAR SUBSECTION 2.4.1 LIST OF TABLES Number Title 2.4.1-201 East Miami-Dade County Drainage Subbasin Areas and Outfall Structures 2.4.1-202 Summary of Data Records for Gage Stations at S-197, S-20, S-21A, and S-21 Flow Control Structures 2.4.1-203 Monthly Mean Flows at the Canal C-111 Structure S-197 2.4.1-204 Monthly Mean Water Level at the Canal C-111 Structure S-197 (Headwater) 2.4.1-205 Monthly Mean Flows in the Canal L-31E at Structure S-20 2.4.1-206 Monthly Mean Water Levels in the Canal L-31E at Structure S-20 (Headwaters) 2.4.1-207 Monthly Mean Flows in the Princeton Canal at Structure S-21A 2.4.1-208 Monthly Mean Water Levels in the Princeton Canal at Structure S-21A (Headwaters) 2.4.1-209 Monthly Mean Flows in the Black Creek Canal at Structure S-21 2.4.1-210 Monthly Mean Water Levels in the Black Creek Canal at Structure S-21 2.4.1-211 NOAA -

Movements, Fishery Interactions, and Unusual Mortalities of Bottlenose Dolphins

MOVEMENTS, FISHERY INTERACTIONS, AND UNUSUAL MORTALITIES OF BOTTLENOSE DOLPHINS by STEVE F. SHIPPEE B.S. University of West Florida, 1983 Professional Certificate in Natural Resource Management, University of California San Diego, 2001 A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of Biology in the College of Sciences at the University of Central Florida Orlando, Florida Spring Term 2014 Major Professor: Graham A.J. Worthy © 2014 Steve F. Shippee ii ABSTRACT Bottlenose dolphins (Tursiops truncatus) inhabit coastal and estuarine habitats across the globe. Well-studied dolphin communities thrive in some peninsular Florida bays, but less is known about dolphins in the Florida panhandle where coastal development, storms, algal blooms, fishery interactions, and catastrophic pollution have severely impacted their populations. Dolphins can react to disturbance and environmental stressors by modifying their movements and habitat use, which may put them in jeopardy of conflict with humans. Fishery interaction (FI) plays an increasing role in contributing to dolphin mortalities. I investigated dolphin movements, habitat use, residency patterns, and frequency of FI with sport fishing. Dolphins were tracked using radio tags and archival data loggers to determine fine-scale swimming, daily travels, and foraging activity. Dolphin abundance, site fidelity, ranging, stranding mortality, and community structure was characterized at Choctawhatchee and Pensacola Bays in the Florida Panhandle via small boat surveying and photo-identification. Reported increases in dolphin interactions with sport anglers were assessed at deep sea reefs and coastal fishing piers near Destin, FL and Orange Beach, AL. Results from these studies yield insights into the ranging and foraging patterns of bottlenose dolphins, and increase our knowledge of them in the northern Gulf of Mexico. -

Gulf of Mexico Estuary Program Restoration Council (EPA RESTORE 003 008 Cat1)

Gulf Coast Gulf-wide Foundational Investment Ecosystem Gulf of Mexico Estuary Program Restoration Council (EPA_RESTORE_003_008_Cat1) Project Name: Gulf of Mexico Estuary Program – Planning Cost: Category 1: $2,200,000 Responsible Council Member: Environmental Protection Agency Partnering Council Member: State of Florida Project Details: This project proposes to develop and stand-up a place-based estuary program encompassing one or more of the following bays in Florida’s northwest panhandle region: Perdido Bay, Pensacola Bay, Escambia Bay, Choctawhatchee Bay, St. Andrews Bay and Apalachicola Bay. Activities: The key components of the project include establishing the host organization and hiring of key staff, developing Management and Technical committees, determining stressors and then developing and approving a Comprehensive Plan. Although this Estuary Program would be modeled after the structure and operation of National Estuary Programs (NEP) it would not be a designated NEP. This project would serve as a pilot project for the Council to consider expanding Gulf-wide when future funds become available. Environmental Benefits: If the estuary program being planned by this activity were implemented in the future, projects undertaken would directly support goals and outcomes focusing on restoring water quality, while also addressing restoration and conservation of habitat, replenishing and protecting living coastal and marine resources, enhancing community resilience and revitalizing the coastal economy. Specific actions would likely include, -

Interpretation of Fish Shoal Indications in the Arabian Sea

INTERPRETATION OF FISH SHOAL INDICATIONS IN THE ARABIAN SEA V. A. Puthran & V. Narayana Pillai Central institute of Fisheries Operatives, Cachill. Jntroduction Some knowledge regardir.g the pre sence of similar fishable concentrations Availability of resources is perhaps of fish and other marine life is of great one of the most il1)p~rt2nt factors which importance to the technical ski:] working determines the success of any industry. on board fishing vess" ls. Their technical In the case of the fishing industry, at the knowledoe in fishing could be put to basic production level. the availability use more-eifectively ..,>,hen posit ive indi of fishable concentrations of fishes and cations with regard to the avaiiability of other mHine life is the decisive factor shoals are known to them. The correct which c~ntrols the economy of the whole and quick interpretation of these indi system. Even when well e quipped cations would Dlace them in a better vessel, fishing gear an d trained person position from where they can use their nelare available, the success of the indu judgment towards achieving great stry is dependent on the availability of success in this endeavour. fishable concentrations of commercially important marine life at the appropriate In India, only very little werk seems time. By the word' fishable concentra to have been done along these lines tions', the implication is availability of especially to arrive at a positive corre sizeable quantities of fishes which could lation between certain natural indica be definitely caught using a particular tions and presence of fishable concent type of craft and gear in a particular rations of comITl "rciallv important area at a particular time. -

Effects of a Shallow Flood Shoal and Friction on Hydrodynamics of A

PUBLICATIONS Journal of Geophysical Research: Oceans RESEARCH ARTICLE Effects of a shallow flood shoal and friction on hydrodynamics 10.1002/2016JC012502 of a multiple-inlet system Key Points: Mara M. Orescanin1 , Steve Elgar2 , Britt Raubenheimer2 , and Levi Gorrell2 A flood shoal can act as a tidal reflector and limit the influence of an 1Oceanography Department, Naval Postgraduate School, Monterey, California, USA, 2Applied Ocean Physics and inlet in a multiple-inlet system Engineering, Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution, Woods Hole, Massachusetts, USA The effects of inertia, friction, and the flood shoal can be separated with a lumped element model As an inlet lengthens, narrows, and Abstract Prior studies have shown that frictional changes owing to evolving geometry of an inlet in a shoals, the lumped element model multiple inlet-bay system can affect tidally driven circulation. Here, a step between a relatively deep inlet shows the initial dominance of the and a shallow bay also is shown to affect tidal sea-level fluctuations in a bay connected to multiple inlets. shoal is replaced by friction To examine the relative importance of friction and a step, a lumped element (parameter) model is used that includes tidal reflection from the step. The model is applied to the two-inlet system of Katama Inlet (which Correspondence to: M. M. Orescanin, connects Katama Bay on Martha’s Vineyard, MA to the Atlantic Ocean) and Edgartown Channel (which con- [email protected] nects the bay to Vineyard Sound). Consistent with observations and previous numerical simulations, the lumped element model suggests that the presence of a shallow flood shoal limits the influence of an inlet.