Heat-Related Retaliation in Baseball DOI: 10.1177/0956797611399292

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

NCAA Division I Baseball Records

Division I Baseball Records Individual Records .................................................................. 2 Individual Leaders .................................................................. 4 Annual Individual Champions .......................................... 14 Team Records ........................................................................... 22 Team Leaders ............................................................................ 24 Annual Team Champions .................................................... 32 All-Time Winningest Teams ................................................ 38 Collegiate Baseball Division I Final Polls ....................... 42 Baseball America Division I Final Polls ........................... 45 USA Today Baseball Weekly/ESPN/ American Baseball Coaches Association Division I Final Polls ............................................................ 46 National Collegiate Baseball Writers Association Division I Final Polls ............................................................ 48 Statistical Trends ...................................................................... 49 No-Hitters and Perfect Games by Year .......................... 50 2 NCAA BASEBALL DIVISION I RECORDS THROUGH 2011 Official NCAA Division I baseball records began Season Career with the 1957 season and are based on informa- 39—Jason Krizan, Dallas Baptist, 2011 (62 games) 346—Jeff Ledbetter, Florida St., 1979-82 (262 games) tion submitted to the NCAA statistics service by Career RUNS BATTED IN PER GAME institutions -

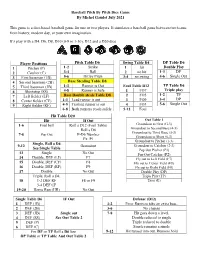

Baseball Pitch by Pitch Dice Game Instruction

Baseball Pitch By Pitch Dice Game By Michel Gaudet July 2021 This game is a dice-based baseball game for one or two players. It simulates a baseball game between two teams from history, modern day, or your own imagination. It’s play with a D4. D6, D8, D10 (0-9 or 1-10), D12 and a D20 dice. Player Positions Pitch Table D6 Swing Table D4 DP Table D6 1 Pitcher (P) 1-2 Strike 1 hit Double Play 2 Catcher (C) 3-4 Ball 2 no hit 1-3 DP 3 First baseman (1B) 5-6 Hit by Pitch 3-4 no swing 4-6 Single Out 4 Second baseman (2B) Base Stealing Table D8 5 Third baseman (3B) 1-3 Runner is Out Foul Table D12 TP Table D6 6 Shortstop (SS) 4-8 Runner is Safe 1 FO7 Triple play 7 Left fielder (LF) Base Double steals Table D8 2 FO5 1-2 TP 8 Center fielder (CF) 1-3 Lead runner is out 3 FO9 3-4 DP 9 Right fielder (RF) 4-5 Trailing runner is out 4 FO3 5-6 Single Out 6-8 Both runners reach safely 5-12 Foul Hit Table D20 Hit If Out Out Table 1 1-6 Foul ball Roll a D12 (Foul Table) Groundout to First (G-3) Roll a D6 Groundout to Second Base (4-3) Groundout to Third Base (5-3) 7-8 Pop Out P-D6 Number Groundout to Short (6-3) Ex. P1 Groundout to Pitcher (1-3) Single, Roll a D6 9-12 Groundout Groundout to Catcher (2-3) See Single Table Pop Out Pitcher (P1) 13 Single No Out Pop Out Catcher (P2) 14 Double, DEF (LF) F7 Fly out to Left Field (F7) 15 Double, DEF (CF) F8 Fly out to Center Field (F8) 16 Double, DEF (RF) F9 Fly out to Right Field (F9) 17 Double No Out Double Play (DP) Triple, Roll a D4, Triple Play (TP) 18 1-2 DEF RF F8 or F9 Error (E) 3-4 DEF CF 19-20 Home Run (HR) No Out Single Table D6 IF Out Defense (D12) 1 DEF (1B) 1-2 Error Runners take an extra base. -

Testing the Minimax Theorem in the Field

Testing the Minimax Theorem in the Field: The Interaction between Pitcher and Batter in Baseball Christopher Rowe Advisor: Professor William Rogerson Abstract John von Neumann’s Minimax Theorem is a central result in game theory, but its practical applicability is questionable. While laboratory studies have often rejected its conclusions, recent field studies have achieved more favorable results. This thesis adds to the growing body of field studies by turning to the game of baseball. Two models are presented and developed, one based on pitch location and the other based on pitch type. Hypotheses are formed from assumptions on each model and then tested with data from Major League Baseball, yielding evidence in favor of the Minimax Theorem. May 2013 MMSS Senior Thesis Northwestern University Table of Contents Acknowledgements 3 Introduction 4 The Minimax Theorem 4 Central Question and Structure 6 Literature Review 6 Laboratory Experiments 7 Field Experiments 8 Summary 10 Models and Assumptions 10 The Game 10 Pitch Location Model 13 Pitch Type Model 21 Hypotheses 24 Pitch Location Model 24 Pitch Type Model 31 Data Analysis 33 Data 33 Pitch Location Model 34 Pitch Type Model 37 Conclusion 41 Summary of Results 41 Future Research 43 References 44 Appendix A 47 Appendix B 59 2 Acknowledgements I would like to thank everyone who had a role in this paper’s completion. This begins with the Office of Undergraduate Research, who provided me with the funds necessary to complete this project, and everyone at Baseball Info Solutions, in particular Ben Jedlovec and Jeff Spoljaric, who provided me with data. -

Managing Team Chemistry

5/8/2019 Managing Team Chemistry Managing Team Chemistry In a Nutshell I heard a baseball analyst say that the fight between Mike Piazza and Guillermo Mota last week provided a chance for Piazza's team to improve its chemistry. His rationale was pretty complex, but I think he's right. Team chemistry is a complicated issue, but it's also the key to getting the most out of a team's talent. Team chemistry is one of the most complicated keys to the success of organizations. Effective teams are more than just a collection of talented members. To be effective, a team has to be able to combine the efforts and abilities of members in the right way. Just as no two people are identical, no two teams are identical. Consequently, what works well for one team may not work well for others. However, research has identified several factors that usually produce good team chemistry: Diversity Role taking Constructive norms Leadership Cohesiveness Common vision In This Issue Mets Fight for Team Chemistry What We Know About Team Chemistry Managing Team Chemistry About the Newsletter and Subscriptions Good, Clean Joke LeaderLetter Web Site Mets Fight for Team Chemistry I heard Tim Kurkjian explain on an ESPN radio program last week that the incident of Mike Piazza charging to the pitcher's mound to fight Guillermo Mota after Mota hit him with a pitch on March 12 provided an opportunity for Piazza's team, the New York Mets, to improve their chemistry. First, Piazza is a leader on the team and his actions set the tone for the rest of the team. -

2020 Coach Pitch Ground Rules for D2 9/10 Softball All Regular Little

2020 Coach Pitch Ground Rules for D2 9/10 Softball All regular Little League pitching rules are in effect EXCEPT when the following situation occurs: The current pitcher walks 2 consecutive batters and reaches a 4-ball count on the third batter… A designated ‘coach pitcher’ from the hitting team enters the field of play to pitch to the current batter AND the pitcher remains on the field to field the position of pitcher. When the third consecutive walk occurs the count will be reset to 0 balls 0 strikes. The ‘coach’ should be identified prior to the start of the game. It would be preferred that this coach is not one of the base coaches so they may continue to coach the bases and hitter when/if the ball is put into play. The ‘coach’ pitches to the batter while the pitcher fields the position. Balls and strikes are called. The current batter may NOT walk or be hit by pitch, but they may strike out. After the batter puts the ball in play or strikes out, the regular pitcher returns to pitch to face the next batter, unless the third out is recorded. The process begins again. If the pitcher walks 2 consecutive batters and reaches a 4-ball count on the third batter, the ‘coach’ enters the field to pitch again. *If a batted ball strikes the ‘coach’ it will be considered a live ball and be played as such. *The ‘coach pitcher’ is not allowed to coach the hitter—only the base coaches may coach the hitter. -

What Are They Doing There? : William Geoffrey Gehman Lehigh University

Lehigh University Lehigh Preserve Theses and Dissertations 1989 What are they doing there? : William Geoffrey Gehman Lehigh University Follow this and additional works at: https://preserve.lehigh.edu/etd Part of the English Language and Literature Commons Recommended Citation Gehman, William Geoffrey, "What are they doing there? :" (1989). Theses and Dissertations. 4957. https://preserve.lehigh.edu/etd/4957 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by Lehigh Preserve. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Lehigh Preserve. For more information, please contact [email protected]. • ,, WHAT ARE THEY DOING THERE?: ACTING AND ANALYZING SAMUEL BECKETT'S HAPPY DAYS by William Geoffrey Gehman A Thesis Presented to the Graduate Committee of Lehigh University 1n Candidacy for the Degree of Master of Arts 1n English Lehigh University 1988 .. This thesis 1S accepted and approved in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts. (date) I Professor 1n Charge Department Chairman 11 ACD01fLBDGBNKNTS ., Thanks to Elizabeth (Betsy) Fifer, who first suggested Alan Schneider's productions of Samuel Beckett's plays as a thesis topic; and to June and Paul Schlueter for their support and advice. Special thanks to all those interviewed, especially Martha Fehsenfeld, who more than anyone convinced the author of Winnie's lingering presence. 111 TABLB OF CONTBNTS Abstract ...................•.....••..........•.•••••.••.••• 1 ·, Introduction I Living with Beckett's Standards (A) An Overview of Interpreting Winnie Inside the Text ..... 3 (B) The Pros and Cons of Looking for Clues Outside the Script ................................................ 10 (C) The Play in Context .................................. -

Baseball Northern Territory Interim Reported Player & Tribunal Procedures

Unit 4, 28 Tambling Tce, Lyons NT 0810 PO Box 40329, Casuarina NT 0810 [email protected] facebook.com/territorybaseball ABN: 48 275 166 266 0407 733 792 BASEBALL NORTHERN TERRITORY INTERIM REPORTED PLAYER & TRIBUNAL PROCEDURES As of 12 March 2020 TABLE OF CONTENTS REPORTED PLAYER & TRIBUNAL PROCEDURE p.1 Reporting Procedures p.1 Tribunal Chairman Procedures p.2 Pre-Tribunal Hearing Procedures p.3 Tribunal Hearing Procedures p.6 Reopening a Tribunal Hearing p.10 APPENDIX A p.11 Recommended Penalties and Offence Definitions p.11 a) Class A Offences p.12 b) Class B Offences p.13 c) Class C Offences p.14 APPENDIX B p.15 Notice Form for Reported Player p.15 APPEAL - TRIBUNAL DECISION p.16 Notice of Appeal p.16 Appeals Officer p.16 Grounds for an Appeal p.16 Appeals Committee p.17 Proceedings of Appeals Committee p.17 Powers of the Appeals Committee p.17 Appeal of Appeal Committee Decision p.18 APPEAL - TRIBUNAL PROCEDURE p.18 Notice of Appeal p.18 Appeals Officer p.18 Grounds for an Appeal p.19 Appeals Committee p.20 Proceedings of Appeals Committee p.21 Appeal of Appeal Committee Decision p.23 1 Unit 4, 28 Tambling Tce, Lyons NT 0810 PO Box 40329, Casuarina NT 0810 [email protected] facebook.com/territorybaseball ABN: 48 275 166 266 0407 733 792 REPORTED PLAYER & TRIBUNAL PROCEDURE REPORTING PROCEDURES 1. Any umpire in control of any Baseball Northern Territory (BNT) and/or Darwin Baseball League (DBL) and/or Alice Springs Baseball Association (ASBA) game may report any person who engages in conduct detrimental to the best interests of the game of baseball. -

National Pastime a REVIEW of BASEBALL HISTORY

THE National Pastime A REVIEW OF BASEBALL HISTORY CONTENTS The Chicago Cubs' College of Coaches Richard J. Puerzer ................. 3 Dizzy Dean, Brownie for a Day Ronnie Joyner. .................. .. 18 The '62 Mets Keith Olbermann ................ .. 23 Professional Baseball and Football Brian McKenna. ................ •.. 26 Wallace Goldsmith, Sports Cartoonist '.' . Ed Brackett ..................... .. 33 About the Boston Pilgrims Bill Nowlin. ..................... .. 40 Danny Gardella and the Reserve Clause David Mandell, ,................. .. 41 Bringing Home the Bacon Jacob Pomrenke ................. .. 45 "Why, They'll Bet on a Foul Ball" Warren Corbett. ................. .. 54 Clemente's Entry into Organized Baseball Stew Thornley. ................. 61 The Winning Team Rob Edelman. ................... .. 72 Fascinating Aspects About Detroit Tiger Uniform Numbers Herm Krabbenhoft. .............. .. 77 Crossing Red River: Spring Training in Texas Frank Jackson ................... .. 85 The Windowbreakers: The 1947 Giants Steve Treder. .................... .. 92 Marathon Men: Rube and Cy Go the Distance Dan O'Brien .................... .. 95 I'm a Faster Man Than You Are, Heinie Zim Richard A. Smiley. ............... .. 97 Twilight at Ebbets Field Rory Costello 104 Was Roy Cullenbine a Better Batter than Joe DiMaggio? Walter Dunn Tucker 110 The 1945 All-Star Game Bill Nowlin 111 The First Unknown Soldier Bob Bailey 115 This Is Your Sport on Cocaine Steve Beitler 119 Sound BITES Darryl Brock 123 Death in the Ohio State League Craig -

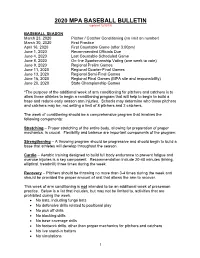

2020 MPA BASEBALL BULLETIN (Updated 12/10/19)

2020 MPA BASEBALL BULLETIN (updated 12/10/19) BASEBALL SEASON March 23, 2020 Pitcher / Catcher Conditioning (no limit on number) March 30, 2020 First Practice April 16, 2020 First Countable Game (after 3:00pm) June 1, 2020 Recommended Officials Due June 4, 2020 Last Countable Scheduled Game June 8, 2020 On-line Sportsmanship Voting (one week to vote) June 9, 2020 Regional Prelim Games June 11, 2020 Regional Quarter-Final Games June 13, 2020 Regional Semi-Final Games June 16, 2020 Regional Final Games (MPA site and responsibility) June 20, 2020 State Championship Games *The purpose of the additional week of arm conditioning for pitchers and catchers is to allow those athletes to begin a conditioning program that will help to begin to build a base and reduce early season arm injuries. Schools may determine who those pitchers and catchers may be, not setting a limit of 8 pitchers and 2 catchers. The week of conditioning should be a comprehensive program that involves the following components: Stretching – Proper stretching of the entire body, allowing for preparation of proper mechanics, is crucial. Flexibility and balance are important components of the program. Strengthening – A throwing program should be progressive and should begin to build a base that athletes will develop throughout the season. Cardio – Aerobic training designed to build full body endurance to prevent fatigue and overuse injuries is a key component. Recommendation include 20-40 minutes (biking, elliptical, treadmill) three times during the week. Recovery – Pitchers should be throwing no more than 3-4 times during the week and should be provided the proper amount of rest that allows the arm to recover. -

WCBC Rule Book 2020 Season

WCBC Rule Book 2020 Season West Carrollton Baseball Club 2020 Rule Book PREFACE The handbook contains the rules and regulations for the 2020 season of West Carrollton Baseball Club (hereinafter “WCBC”). Every attempt has been made to minimize the number of rules and make them fair to all participants. We urge everyone to take the time to read these rules so that there is a clear understanding of the rules and regulations. Any rules not covered by this WCBC rule book will be governed by the Ohio High School Baseball Rule Book. Managers are encouraged to keep a copy of these rules with them at games. I. PURPOSES AND OBJECTIVES a. The purpose of WCBC is to provide baseball for as many as possible in the community, to teach basic knowledge of the game, to develop character and to win and lose in sportsmanlike manner. II. LEAGUE STRUCTURE a. The following divisions will be offered by WCBC i. 6U – T-Ball (cannot turn 7 before May 1, 2014) 1. Exceptions can be made at the discretion of WCBC executive board ii. 8U – Coach Pitch (cannot turn 9 before May 1, 2012) iii. 10U – Kid Pitch (cannot turn 11 before May 1, 2010) iv. 12U – Kid Pitch (cannot turn 13 before May 1, 2008) b. There are no set number of games guaranteed in any division. WCBC will make every effort to make up rain out games but they are not guaranteed. III. VIOLATION OF RULES a. Head coaches, assistant coaches, and volunteers who violate any WCBC rule will be subject to review by the WCBC Board and may be removed from his/her position, role of duty. -

Baseball/Softball

SAMPLE SITUTATIONS Situation Enter for batter Enter for runner Hit (single, double, triple, home run) 1B or 2B or 3B or HR Hit to location (LF, CF, etc.) 3B 9 or 2B RC or 1B 6 Bunt single 1B BU Walk, intentional walk or hit by pitch BB or IBB or HP Ground out or unassisted ground out 63 or 43 or 3UA Fly out, pop out, line out 9 or F9 or P4 or L6 Pop out (bunt) P4 BU Line out with assist to another player L6 A1 Foul out FF9 or PF2 Foul out (bunt) FF2 BU or PF2 BU Strikeouts (swinging or looking) KS or KL Strikeout, Fouled bunt attempt on third strike K BU Reaching on an error E5 Fielder’s choice FC 4 46 Double play 643 GDP X Double play (on strikeout) KS/L 24 DP X Double play (batter reaches 1B on FC) FC 554 GDP X Double play (on lineout) L63 DP X Triple play 543 TP X (for two runners) Sacrifi ce fl y F9 SF RBI + Sacrifi ce bunt 53 SAC BU + Sacrifi ce bunt (error on otherwise successful attempt) E2T SAC BU + Sacrifi ce bunt (no error, lead runner beats throw to base) FC 5 SAC BU + Sacrifi ce bunt (lead runner out attempting addtional base) FC 5 SAC BU + 35 Fielder’s choice bunt (one on, lead runner out) FC 5 BU (no sacrifi ce) 56 Fielder’s choice bunt (two on, lead runner out) FC 5 BU (no sacrifi ce) 5U (for lead runner), + (other runner) Catcher or batter interference CI or BI Runner interference (hit by batted ball) 1B 4U INT (awarded to closest fi elder)* Dropped foul ball E9 DF Muff ed throw from SS by 1B E3 A6 Batter advances on throw (runner out at home) 1B + T + 72 Stolen base SB Stolen base and advance on error SB E2 Caught stealing -

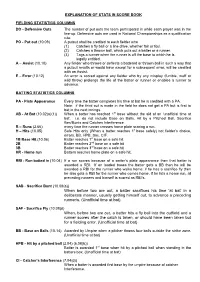

How to Do Stats

EXPLANATION OF STATS IN SCORE BOOK FIELDING STATISTICS COLUMNS DO - Defensive Outs The number of put outs the team participated in while each player was in the line-up. Defensive outs are used in National Championships as a qualification rule. PO - Put out (10.09) A putout shall be credited to each fielder who (1) Catches a fly ball or a line drive, whether fair or foul. (2) Catches a thrown ball, which puts out a batter or a runner. (3) Tags a runner when the runner is off the base to which he is legally entitled. A – Assist (10.10) Any fielder who throws or deflects a battered or thrown ball in such a way that a putout results or would have except for a subsequent error, will be credited with an Assist. E – Error (10.12) An error is scored against any fielder who by any misplay (fumble, muff or wild throw) prolongs the life of the batter or runner or enables a runner to advance. BATTING STATISTICS COLUMNS PA - Plate Appearance Every time the batter completes his time at bat he is credited with a PA. Note: if the third out is made in the field he does not get a PA but is first to bat in the next innings. AB - At Bat (10.02(a)(1)) When a batter has reached 1st base without the aid of an ‘unofficial time at bat’. i.e. do not include Base on Balls, Hit by a Pitched Ball, Sacrifice flies/Bunts and Catches Interference. R – Runs (2.66) every time the runner crosses home plate scoring a run.