Senate Inquiry Into Environmental Offsets

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Report to Office of Water Science, Department of Science, Information Technology and Innovation, Brisbane

Lake Eyre Basin Springs Assessment Project Hydrogeology, cultural history and biological values of springs in the Barcaldine, Springvale and Flinders River supergroups, Galilee Basin and Tertiary springs of western Queensland 2016 Department of Science, Information Technology and Innovation Prepared by R.J. Fensham, J.L. Silcock, B. Laffineur, H.J. MacDermott Queensland Herbarium Science Delivery Division Department of Science, Information Technology and Innovation PO Box 5078 Brisbane QLD 4001 © The Commonwealth of Australia 2016 The Queensland Government supports and encourages the dissemination and exchange of its information. The copyright in this publication is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Australia (CC BY) licence Under this licence you are free, without having to seek permission from DSITI or the Commonwealth, to use this publication in accordance with the licence terms. You must keep intact the copyright notice and attribute the source of the publication. For more information on this licence visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/au/deed.en Disclaimer This document has been prepared with all due diligence and care, based on the best available information at the time of publication. The department holds no responsibility for any errors or omissions within this document. Any decisions made by other parties based on this document are solely the responsibility of those parties. Information contained in this document is from a number of sources and, as such, does not necessarily represent government or departmental policy. If you need to access this document in a language other than English, please call the Translating and Interpreting Service (TIS National) on 131 450 and ask them to telephone Library Services on +61 7 3170 5725 Citation Fensham, R.J., Silcock, J.L., Laffineur, B., MacDermott, H.J. -

Galilee Basin Thermal Coal Prohibition Bill Submission

Galilee Basin Thermal Coal Prohibition Bill Submission This submission relates to the proposed Bill for an Act to prohibit the mining of thermal coal in the Galilee Basin. The Black-throated Finch Recovery Team is a community-based group whose mission is to secure the conservation of the Black-throated Finch (southern subspecies) Poephila cincta cincta which is listed as Endangered under the Commonwealth Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act 1999 (EPBC Act) as well as under Queensland and New South Wales state legislation. The proposed Bill is relevant to the conservation of the Black-throated Finch because of the vital importance of the Galilee Basin as a stronghold for the species. Portions of the Galilee Basin provide high quality habitat in narrow-leaf ironbark (Eucalyptus crebra) and other woodlands and these areas support the highest know densities and largest known surviving populations of the bird. The only other area known to support relatively large populations is the Townsville Coastal Plain where the species is threatened by urban expansion, intensive livestock grazing and vegetation change, including weed invasion. The species is rare, if not extinct, further south in Queensland and in New South Wales. Open-cut and underground coal mining present a major threat to the populations of Black- throated Finch in the Galilee Basin. These threats relate to mine footprints themselves, which can be substantial, especially in the case of open-cut mining, and to the direct and indirect effects of mining-related infrastructure. Offsets, as proposed for as part of the conditions for approval of developments, such as the Carmichael Mine, do not compensate for loss of habitat and populations of Black-throated Finch and there is the very real risk that there are inadequate areas suitable for offsets. -

Why Do Coal Mines Need So Much Water? 13 April 2017, by Ellen Moon

Why do coal mines need so much water? 13 April 2017, by Ellen Moon as a water-based slurry for further processing. Mines also need water for things like equipment maintenance, and for consumption by the mining communities themselves. In total, about 250 litres of freshwater are required per tonne of coal produced. This freshwater makes up around a quarter of the total water demand during coal production, the rest being "worked" (recycled) water. Coal mines, such as this one near Bowen, use water for What other industries use lots of water? everything from equipment cooling to dust management. Credit: CSIRO, CC BY The Great Artesian Basin is one of the largest underground water reservoirs in the world. It underlies 22% of Australia's land area, beneath the arid and semi-arid parts of Queensland, New South From accidental water spills into coastal wetlands, Wales, South Australia and the Northern Territory. to proposed taxpayer-funded loans, Adani's planned Carmichael coal mine and the associated Its aquifers supply water to around 200 towns or Abbot Point coal terminal can't keep out of the settlements, most of which are allowed to draw news at the moment. between 100 and 500 million litres (ML) per year. Last week, the granting of an unlimited 60-year water licence to the Carmichael mine, in Queensland's Galilee Basin, rattled environmentalists, farmers and community groups alike. In a region experiencing prolonged drought conditions, the provision of unlimited water for one of the largest mining operations in the Southern Hemisphere seems like a commitment at odds with current climate predictions. -

5.4 Galilee Basin Survey 2012 Report.Doc Occur in Proximity to Intact Woodlands.) Waterhole Watches Were Not Used (More Useful in the Dry Season)

bulk email and a handout in Appendix 1 Notices. We were agreeably surprised at the positive response. Many landholders were concerned about the impact of mining on their properties, and made us very welcome. We were given the use of showers and toilets etc. in some delightful campsites. Paola Cassini at Bimblebox even provided us with great meals. One offer of hospitality came directly from the ABC Breakfast Session, and another as a response to the first bulk email in Appendix 1 Survey personnel Sixteen volunteers from BirdLife Southern Queensland (14) and BirdLife Townsville (2) took part. No members from the BTR Recovery Team, BirdLife Capricornia or BirdLife North Queensland were available. The volunteers worked as two independent groups. See Appendix 2 The Team Survey area Initially it had been planned to do three 500m surveys and twelve 2HA Atlas plus Habitat surveys each morning, and optional incidental searches in the afternoons. It soon became apparent that organisation time and distances between sites permitted less surveys – in many cases the 2HA and Habitat surveys were omitted. Survey Sites See list in Appendix 3 Survey Sites. In the Galilee Basin, BTFs had been found in grassy, open woodlands and forests of Regional Ecosystem 10.5.5 - Eucalyptus melanophloia (Silver-leafed Ironbark) open woodland on sand plains. When it became apparent that many of the property managers of the ten properties with this RE were happy to give permission for surveys, it was decided to concentrate on these. It was found that the Stock Routes in the area were all unfenced, and largely unused, so little attention was given to them, and there was no time for the rail corridors, National Parks or Nature Refuges. -

Galilee Basin (Coal Prohibition)

Galilee Basin (Coal Prohibition) Bill 2018 IEEFA’s submission to the Senate Environment and Communications Legislation Committee inquiry into the Galilee Basin (Coal Prohibition) Bill 2018 January 2019 Tim Buckley, Director of Energy Finance Studies, Australasia ([email protected]) Galilee Basin (Coal Prohibition) Bill 2018 1 Table of Contents Executive Summary .............................................................................................................. 3 1. The IEA Sustainable Development Scenario: Coal’s Collapse ............................... 5 2. Financial Institutions Pivot Away from Coal ............................................................... 9 2.1 Japan ..................................................................................................................................... 10 2.2 South Korea ........................................................................................................................... 11 3. India’s Pivot to Renewables........................................................................................12 4. Inferior Galilee Coal Quality ......................................................................................14 4.1 6,000kcal Thermal Coal at US$100/t .................................................................................. 14 4.2 5,500kcal Thermal Coal at a 2018 Low .............................................................................. 15 5. Other Risks .....................................................................................................................18 -

Chapter 22 Conclusion and Recommendations

Chapter 22 Conclusion and recommendations November 2013 Table of contents 22. Conclusion and recommendations ........................................................................................... 22-1 22.1 Purpose of this chapter .................................................................................................. 22-1 22.2 Rationale for NGBR Project ........................................................................................... 22-1 22.3 Economic justification .................................................................................................... 22-2 22.4 Project impacts .............................................................................................................. 22-2 22.4.1 Land use and tenure ........................................................................................... 22-2 22.4.2 Topography, geology, soils and land contamination .......................................... 22-3 22.4.3 Nature conservation ........................................................................................... 22-3 22.4.4 Matters of national environmental significance .................................................. 22-4 22.4.5 Greenhouse gas ................................................................................................. 22-5 22.4.6 Cultural heritage ................................................................................................. 22-5 22.4.7 Social and economic impacts ............................................................................ -

VARIATION of CONDITIONS ATTACHED to APPROVAL Carmichael Coal Mine and Rail Infrastructure Project, Queensland (EPBC 2010/5736)

~£~" _A_u_st_r_a_Ji_a_D_G_o_V_C_I'"_D__ffi _e_"_t ~ Department of the Environment and Energy VARIATION OF CONDITIONS ATTACHED TO APPROVAL Carmichael Coal Mine and Rail Infrastructure Project, Queensland (EPBC 2010/5736) This decision to vary conditions of approval is made under section 143 of the Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act 1999 (EPBC Act). Approved action Person to whom the Adani Mining Pty Ltd approval is granted ACN: 145455205 Approved action To develop an open cut and underground coal mine, 189 km rail link and associated infrastructure approximately 160 km north west of Clermont in central Queensland [see EPBC Act referral 2010/5736 and approved variations dated 19 April 2012, 9 October 2012 and 24 July 2013] Variation Variation of conditions The variation is: attached to approval Delete conditions 8 and 11 attached to the approval and substitute with the conditions specified below. Delete the definition of the Galilee Basin Strategic Offset Strategy. Insert a new definition of Galilee Basin Offset Strategy as specified below. Date of effect This variation has effect on the date the instrument is signed Person authorised to make decision Name and position Chris Videroni Acting Assistant Secretary Assessme and Post Approvals Branch Signature Date of decision Varied condition As varied on 8. The approval holder must legally secure the minimum offset areas detailed in Table 1 for the date of the rail (west) component within four years of commencement of the specified component of this notice the action. The approval holder must legally secure the minimum offset areas for the other specified components detailed in Table 1 within two years of commencement of those specified components of the action. -

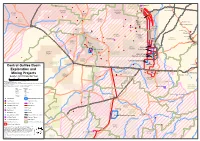

Central Galilee Basin Exploration and Mining Projects

North Goonyella* QUEENSLAND ENERGY RESOURCES Eaglefield* CHARTERS # China Stone* TOWERS CARMICHAEL " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " R FLINDERS REGIONAL AILWAY " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " QUEENSLAND " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " # LONGREACH SHIRE Twin Hills Gold ENERGY " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " Grosvenor* NUMBER 2 " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " RESOURCES PANGAEA PTY LTD " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " GALILEE GALILEE LIMITED " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " Y PTY LTD RESOURCES A PANGAEA " " " " " " " " "#" " " " " " " " " W L PTY LTD " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " I A Isaac Plains South GALILEE " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " R # PTY LTD Carm"ic"ha" e" l*" " " " " " " " " " " " " " DIAMOND GALILEE " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " CREEK COAL RESOURCES " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " PTY LTD WINTON " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " PTY LTD " " " C" O" M" E"T " " " " " " " " " " " RIVER QUEENSLAND SHIRE " " " R" ID" G" E" " " " " " " " " " " " Belyando Gold ENERGY " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " # RESOURCE" S" " " L"TD" " " " " " " " " " " " " WESTERN # LIMITED " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " Anthony Molybdenum WINTON " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " ! " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " Y QUEENSLAND A # " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " Gunn CSG W " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " ENERGY IL " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " A RESOURCES R " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " L C LIMITED A E " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " O N C -

Hydrogeological Overview of Springs in the Great Artesian Basin

Hydrogeological Overview of Springs in the Great Artesian Basin M. A. (Rien) Habermehl1 Abstract The Great Artesian Basin (GAB) is a regional groundwater system consisting of aquifers and confining beds within the sedimentary Eromanga, Surat and Carpentaria Basins. They under- lie arid to semi-arid regions across 1.7 million km2, or one-fifth of the Australian continent. Artesian springs of the GAB are naturally occurring outlets of groundwater from the confined aquifers. Springs predominantly occur near the eastern recharge margins and the south-western and western discharge margins of the GAB. These zones of natural groundwater discharge represent areas of permanent water, with widely recognised cultural, spiritual and subsistence importance to Indigenous people for tens of thousands of years. The unique hydrogeological environments – discharge, hydrochemistry and substrate – support a range of endemic flora and fauna protected under the EPBC Act (1999). Springs have formed in many areas across the GAB; however, the largest concentrations occur near the south-western margins of the basin. Supporting these flowing artesian springs is a multi-layered aquifer system, comprising Jurassic- to Cretaceous-age sandstones and siltstone, and confining beds of mudstones. Hydrogeological, hydrochemical and isotope hydrology studies show that most artesian springs and flowing water bores in the GAB derive their water from the main Jurassic–Lower Cretaceous Cadna-owie Formation – Hooray Sandstone aquifer and its equivalents. Focusing on springs in South Australia, this paper provides a summary of the hydrogeology of the GAB, including zones of recharge and regional groundwater flow directions, with a major focus on summarising under- standing of the occurrence and formation of springs. -

The Structure, Sedimentology, Sequence Stratigraphy and Tectonics of the Northern Drummond and Galilee Basins, Central Queensland, Australia

THE STRUCTURE, SEDIMENTOLOGY, SEQUENCE STRATIGRAPHY AND TECTONICS OF THE NORTHERN DRUMMOND AND GALILEE BASINS, CENTRAL QUEENSLAND, AUSTRALIA Volume I Thesis submitted by Aldo Van Heeswijck MScStud (Newcastle) Dip Ed in February 2006 for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of Earth Sciences, James Cook University of North Queensland STATEMENT OF ACCESS I, the undersigned, author of this work, understand that James Cook University will make this thesis available for use within the University Library and, via the Australian Digital Thesis network, for use elsewhere. All users consulting this thesis will have to sign the following statement: “In consulting this thesis I agree not to copy closely or to paraphrase it in whole or in part without the written consent of the author, and to make proper written acknowledgement for any assistance I obtained from it.” I understand that, as an unpublished work, a thesis has significant protection under the Copyright Act. Most of the work in this thesis is intended for publication in scientific journals and any such work should be acknowledged accordingly. Beyond this, I do not wish to place any restrictions on this thesis. Signature Date ii ELECTRONIC COPY I, the undersigned, the author of this work, declare that the electronic copy of this thesis provided to the James Cook University Library, is an accurate copy of the print thesis submitted, within the limits of the technology available. _______________________________ _______________ Signature Date Signed on behalf of Aldo van Heeswijck by Head of School of Earth & Environmental Sciences, JCU DECLARATION I declare that this thesis is my own work and has not been submitted in any form for another degree or diploma at any university or other institution of tertiary education. -

Galilee Basin Jobs Impact

The impact of Galilee Basin development on employment in existing coal regions Development of the Galilee Basin would displace production in other coal regions. Galilee mines would be more automated and less job-intensive than existing mines. Based on coal industry analysis, central estimates of employment reduction are 9,100 in the Hunter Valley, 2,000 in the Bowen Basin & 1,400 in the Surat Basin compared to a no-Galilee scenario. Galilee mines are likely to employ between 7,840 and 9,800 people, resulting in overall negative impact on coal jobs. Discussion paper Cameron Murray Bill Browne Rod Campbell July 2018 ABOUT THE AUSTRALIA INSTITUTE The Australia Institute is an independent public policy think tank based in Canberra. It is funded by donations from philanthropic trusts and individuals and commissioned research. We barrack for ideas, not political parties or candidates. Since its launch in 1994, the Institute has carried out highly influential research on a broad range of economic, social and environmental issues. OUR PHILOSOPHY As we begin the 21st century, new dilemmas confront our society and our planet. Unprecedented levels of consumption co-exist with extreme poverty. Through new technology we are more connected than we have ever been, yet civic engagement is declining. Environmental neglect continues despite heightened ecological awareness. A better balance is urgently needed. The Australia Institute’s directors, staff and supporters represent a broad range of views and priorities. What unites us is a belief that through a combination of research and creativity we can promote new solutions and ways of thinking. OUR PURPOSE – ‘RESEARCH THAT MATTERS’ The Institute publishes research that contributes to a more just, sustainable and peaceful society. -

Detecting Inter-Aquifer Leakage in Areas with Limited Data Using Hydraulics and Multiple Environmental Tracers, Including 4He, 36Cl/Cl, 14Cand87sr/86Sr

Hydrogeol J DOI 10.1007/s10040-017-1609-x REPORT Detecting inter-aquifer leakage in areas with limited data using hydraulics and multiple environmental tracers, including 4He, 36Cl/Cl, 14Cand87Sr/86Sr Stacey C. Priestley 1 & Daniel L. Wohling2 & Mark N. Keppel2 & Vincent E. A. Post 1 & Andrew J. Love1 & Paul Shand 1,3 & Lina Tyroller4 & Rolf Kipfer4,5 Received: 6 December 2016 /Accepted: 19 May 2017 # The Author(s) 2017. This article is an open access publication Abstract The investigation of regionally extensive ground- controlled by diffuse inter-aquifer leakage, but the coarse spa- water systems in remote areas is hindered by a shortage of data tial resolution means that the presence of additional enhanced due to a sparse observation network, which limits our under- inter-aquifer leakage sites cannot be excluded. This study standing of the hydrogeological processes in arid regions. The makes the case that a multi-tracer approach along with study used a multidisciplinary approach to determine hydrau- groundwater hydraulics and geology provides a tool-set to lic connectivity between the Great Artesian Basin (GAB) and investigate enhanced inter-aquifer leakage even in a ground- the underlying Arckaringa Basin in the desert region of water basin with a paucity of data. A particular problem en- Central Australia. In order to manage the impacts of ground- countered in this study was the ambiguous interpretation of water abstraction from the Arckaringa Basin, it is vital to different age tracers, which is attributed to diffusive transport understand its connectivity with the GAB (upper aquifer), as across flow paths caused by low recharge rates.