Representing the Child's Memory: an Ulster

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

County Donegal

Local Electoral Area Boundary Committee No. 1 Report 2018 County Donegal Letterkenny LEA - 7 ARDMALIN Milford LEA - 3 MALIN CARTHAGE Carndonagh LEA - 4 Carndonagh BALLYLIFFIN CULDAFF MÍN AN CHLADAIGH TURMONE DUNAFF " FÁNAID THUAIDH STRAID CARNDONAGH GLENEELY GREENCASTLE GLENEGANON ROS GOILL FÁNAID THIAR GRIANFORT MOVILLE DÚN FIONNACHAIDH DESERTEGNY CASTLECARY ROSNAKILL MINTIAGHS GLENTOGHER REDCASTLE ILLIES ARDS CARRAIG AIRT AN CHEATHRÚ CHAOL Buncrana WHITECASTLE CREAMHGHORT CNOC COLBHA BUNCRANA URBAN BUNCRANA RURAL KILLYGARVAN MÍN AN CHLADAIGH GLEN Milford THREE TREES CRÍOCH NA SMÉAR CAISLEÁN NA DTUATH RATHMULLAN " GORT AN CHOIRCE NA CROISBHEALAÍ AN CRAOSLACH MILLFORD GLENALLA FAHAN KILDERRY " BIRDSTOWN LOCH CAOL INCH ISLAND AN TEARMANN BALLYARR Buncrana LEA - 5 MACHAIRE CHLOCHAIR KILMACRENAN INIS MHIC AN DOIRN DÚN LÚICHE RATHMELTON BURT ANAGAIRE Glenties LEA - 6 GARTÁN Letterkenny GORTNAVERN ÁRAINN MHÓR INIS MHIC AN DOIRN EDENACARNAN CASTLEFORWARD CASTLEWRAY TEMPLEDOUGLAS NEWTOWN CUNNINGHAM " MANORCUNNINGHAM MÍN AN LÁBÁIN LETTERKENNY RURAL KILLEA AN CLOCHÁN LIATH CRÓ BHEITHE LETTERKENNY URBAN AN DÚCHORAIDH BALLYMACOOL TREANTAGHMUCKLAGH SUÍ CORR KILLYMASNY MAGHERABOY AN MACHAIRE ST. JOHNSTOWN MÍN CHARRAIGEACH CORRAVADDY KINCRAIGY BAILE NA FINNE FEDDYGLASS FIGART LETTERMORE LEITIR MHIC AN BHAIRD CLONLEIGH NORTH GLEANN LÉITHÍN CONVOY RAPHOE Local Electoral Areas AN CLOCHÁN " Lifford Stranorlar CLONLEIGH SOUTH and Municipal Districts: STRANORLAR DAWROS MAAS CASTLEFINN Glenties KILLYGORDON Local Electoral Areas: NA GLEANNTA AN GHRAFAIDH " -

Malin Head Tourist Map (Printing)

BANBA'S CROWN & DUNALDERAGH - WILD ATLANTIC WAY SIGNATURE DISCOVERY POINT & IRELAND'S MOST NORTHERLY POINT BALLYHILLIN MALIN HEAD RD LOCAL (3 CLASS) ROADS CURIOSITY SHOP WILD ATLANTIC WAY - NATIONAL SCENIC ROUTE INISHOWEN 100 - LOCAL SCENIC ROUTE ARDMALIN PEDESTRIAN PATH / TRACK / ROUTE ABOUT MALIN HEAD APPROX 0 0.5mile 1 mile SCALE Malin Head is renowned as 0 0.5km 1km Ireland’s most northerly point SCHOOL The word “Malin” comes from BALLYGORMAN Marine Life COMMUNITY The Malin Sea, as a a marginal sea of the North-East the Irish word, Malainn, meaning CENTRE IRISH AVIATION braeface or hillbrow. AUTHORITY RADAR Atlantic, is host to a wide variety of spectacular sea-life. INSTALLATION Basking sharks and bottle-nosed dolphins are regularly Location & Vista's spotted from the various shoreline viewpoints. You may also Malin Head lies 15.3km north of the picturesque glimpse orca / killer whales, minke whales, sunfsh, village of Malin Town, at the very tip of Inishowen, seals and harbour porpoise, as well as porbeagle sharks. COMMUNITY in the eastern most corner of County Donegal. FIELD BREE CROCALOUGH From the various vantage points there are views MULLIN'S Shipwrecks SHOP to the west of Fanad Head lighthouse (which The tempestuous water around Malin Head has become a heralds the entrance to Lough Swilly) and beyond to graveyard of Shipwrecks. There are more Ocean Liners, German U-boats and Sherman Tanks sunk of Malin Head Tory Island, Horn Head, Bloody Foreland and KILLOURT Dunaff Head. To the northeast lies Inishtrahull Island than anywhere else in the World. and looking beyond in the distance, the hills of western Scotland, and the isle of Islay can be seen on a clear day. -

Inishowen Heritage Trail

HERITAGE TRAIL EXPLORE INISHOWEN Inishowen is exceptional in terms of the outstanding beauty of its geography and in the way that the traces of its history survive to this day, conveying an evocative picture of a vibrant past. We invite you to take this fascinating historical tour of Inishowen which will lead you on a journey through its historical past. Immerse yourself in fascinating cultural and heritage sites some of which date back to early settlements, including ancient forts, castle’s, stone circles and high crosses to name but a few. Make this trail your starting point as you begin your exploration of the rich historical tapestry of the Inishowen peninsula. However, there are still hundreds of additional heritage sites left for you to discover. For further reading and background information: Ancient Monuments of Inishowen, North Donegal; Séan Beattie. Inishowen, A Journey Through Its Past Revisited; Neil Mc Grory. www.inishowenheritage.ie www.curiousireland. ie Images supplied by: Adam Porter, Liam Rainey, Denise Henry, Brendan Diver, Ronan O’Doherty, Mark Willett, Donal Kearney. Please note that some of the monuments listed are on private land, fortunately the majority of land owners do not object to visitors. However please respect their property and follow the Country Code. For queries contact Explore Inishowen, Inishowen Tourist Office +353 (0)74 93 63451 / Email: [email protected] As you explore Inishowen’s spectacular Heritage Trail, you’ll discover one of Ireland’s most beautiful scenic regions. Take in the stunning coastline; try your hand at an exhilarating outdoor pursuit such as horse riding, kayaking or surfing. -

East Inishowen Sea Kayak Trail

• Kinnagoe Bay East Inishowen Sea Kayak Trail ... paddle by sandy beaches and cliffs, push around headlands, kayak in the shadow of rocky stacks and through caves! LINKS WITH OTHER TRAILS The Foyle Canoe Trail runs from Lifford to Moville with the section from Culmore Point overlapping part of the Inishowen Trail. Stretching over 22 nautical miles from the start of the River Foyle, this unique trail runs along the tidal river, passing through historic Derry city before following Lough Foyle’s varied coastline to the seaside town of Moville. From the northern end of Lough Foyle, seasoned kayakers can link up with the North Coast Sea Kayak Trail, which begins at Magilligan Point only 1.2 km across the Narrows at Greencastle - plan the crossing carefully, taking into account currents and wind, passage of commercial shipping and fi shing boat operations! WILDLIFE The screeches and calls of cliff nesting • Seal on Inishtrahull bird colonies dominate the soundtrack of this rugged coastline. Fulmar and manx shearwater elegantly skim the surface of the water, ‘shearing’ from side to side as they rhythmically alternate white under parts and dark upper body. Diving terns and soaring gannets (from Ailsa Craig in western Scotland) indicate shoals of fi sh near the surface. Keep a special eye out for the white rumped storm petrel, a dainty ocean wanderer, who patters along the wave tops in summer, fl ying ashore on dark nights to their island nest in some stony crevice. Peregrine and buzzard are cliff top predators with the added excitement of regular eagle sightings in recent years. -

AN INTRODUCTION to the ARCHITECTURAL HERITAGE of COUNTY DONEGAL

AN INTRODUCTION TO THE ARCHITECTURAL HERITAGE of COUNTY DONEGAL AN INTRODUCTION TO THE ARCHITECTURAL HERITAGE of COUNTY DONEGAL COUNTY DONEGAL Mount Errigal viewed from Dunlewey. Foreword County Donegal has a rich architectural seventeenth-century Plantation of Ulster that heritage that covers a wide range of structures became a model of town planning throughout from country houses, churches and public the north of Ireland. Donegal’s legacy of buildings to vernacular houses and farm religious buildings is also of particular buildings. While impressive buildings are significance, which ranges from numerous readily appreciated for their architectural and early ecclesiastical sites, such as the important historical value, more modest structures are place of pilgrimage at Lough Derg, to the often overlooked and potentially lost without striking modern churches designed by Liam record. In the course of making the National McCormick. Inventory of Architectural Heritage (NIAH) The NIAH survey was carried out in phases survey of County Donegal, a large variety of between 2008 and 2011 and includes more building types has been identified and than 3,000 individual structures. The purpose recorded. In rural areas these include structures of the survey is to identify a representative as diverse as bridges, mills, thatched houses, selection of the architectural heritage of barns and outbuildings, gate piers and water Donegal, of which this Introduction highlights pumps; while in towns there are houses, only a small portion. The Inventory should not shopfronts and street furniture. be regarded as exhaustive and, over time, other A maritime county, Donegal also has a rich buildings and structures of merit may come to built heritage relating to the coast: piers, light. -

This Includes Donegal, Sligo, Leitrim

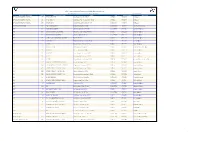

CHO 1 - Service Provider Resumption of Adult Day Services Portal For further information please contact your service provider directly. Last updated 2/03/21 Service Provider Organisation Location Id Day Service Location Name Address Area Telephone Number Email Address ADVOCATES FOR PERSONAL POTENTIAL 3464 APP DONEGAL TOWN Quay Street, Donegal Town, F94 Dr70 DONEGAL 087 1235873 [email protected] ADVOCATES FOR PERSONAL POTENTIAL 521 APP LETTERKENNY Unit Bg9, Justice Walsh Road, Letterkenny, F92 Ye2f DONEGAL 087 1235873 [email protected] ADVOCATES FOR PERSONAL POTENTIAL 2436 APP SLIGO LEITRIM Old Dublin Road, Carrickonshannon, N41 Yy68 SLIGO/LEITRIM 087 1235873 [email protected] GATEWAY COMMUNITY CARE 3610 GCC ACTIVE INCLUSION Ballybeg, Knocknahur, Sligo F91 Dy72 SLIGO/LEITRIM 087 1099406 [email protected] HSE 2440 ACORN RESOURCE CENTRE Clarion Road, Ballytivnan, Sligo F91 Nh51 SLIGO/LEITRIM 071 9148230 [email protected] HSE 2426 AURORA COMMUNITY INCLUSION HUB Milltown House, Tulari, Carndonagh F93 Hw24 DONEGAL 074 9322503 [email protected] HSE 163 BALLYTIVNAN TRAINING CENTRE Clarion Road, Ballytivnan, F91 Nd2n SLIGO/LEITRIM 071 9143214 [email protected] HSE 415 CASHEL NA COR COMMUNITY INCLUSION HUB Buncrana, F93 P527 DONEGAL 074 9321057 [email protected] HSE 3247 CI BALLYRAINE Ballyraine Industrial Estate, Letterkenny, F92 Dy24 DONEGAL 074 9121545 [email protected] HSE 3626 CI DAWN Justice Walsh Road, Letterkenny, F92 Ea2w DONEGAL 074 9200276 [email protected] HSE 3627 CI DONEGAL TOWN Unit B, Quay Street, Donegal -

In Search of Evidence of Cultural Occupation of the Most Northerly Point in Ireland: Focus on Contemporary Irish Archaeology

Loyola University Chicago Loyola eCommons Master's Theses Theses and Dissertations 1981 In Search of Evidence of Cultural Occupation of the Most Northerly Point in Ireland: Focus on Contemporary Irish Archaeology Walter Smithe Loyola University Chicago Follow this and additional works at: https://ecommons.luc.edu/luc_theses Part of the Anthropology Commons Recommended Citation Smithe, Walter, "In Search of Evidence of Cultural Occupation of the Most Northerly Point in Ireland: Focus on Contemporary Irish Archaeology" (1981). Master's Theses. 3224. https://ecommons.luc.edu/luc_theses/3224 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses and Dissertations at Loyola eCommons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Master's Theses by an authorized administrator of Loyola eCommons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 3.0 License. Copyright © 1981 Walter Smithe IN SEARCH OF EVIDENCE OF CULTURAL OCCUPATION OF THE MOST NORTHERLY POINT IN IRELAND: FOCUS ON CONTEMPORARY IRISH ARCHAEOLOGY by Walter Smithe A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate School of Loyola University of Chicago in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts May 1981 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS While submission of a thesis is a singular event, a multitude of activities must precede submission. My determination to success fully complete my studies was always strengthened by my best friend and wife, Flo Flynn Smithe. Her understanding, patience and animated assistance helps me reach the academic goals to which I aspire. Undertaking each new course at Loyola was not without some apprehensions. -

Donegal Primary Care Teams Clerical Support

Donegal Primary Care Teams Clerical Support Office Network PCT Name Telephone Mobile email Notes East Finn Valley Samantha Davis 087 9314203 [email protected] East Lagan Marie Conwell 074 91 41935 086 0221665 [email protected] East Lifford / Castlefin Marie Conwell 074 91 41935 086 0221665 [email protected] Inishowen Buncrana Mary Glackin 074 936 1500 [email protected] Inishowen Carndonagh / Clonmany Christina Donaghy 074 937 4206 [email protected] Fax: 074 9374907 Inishowen Moville Christina Donaghy 074 937 4206 [email protected] Fax: 074 9374907 Letterkenny / North Letterkenny Ballyraine Noelle Glackin 074 919 7172 [email protected] Letterkenny / North Letterkenny Railway House Noelle Glackin 074 919 7172 [email protected] Letterkenny / North Letterkenny Scally Place Margaret Martin 074 919 7100 [email protected] Letterkenny / North Milford / Fanad Samantha Davis 087 9314203 [email protected] North West Bunbeg / Derrybeg Contact G. McGeady, Facilitator North West Dungloe Elaine Oglesby 074 95 21044 [email protected] North West Falcarragh / Dunfanaghy Contact G. McGeady, Facilitator Temporary meeting organisation South Ardara / Glenties by Agnes Lawless, Ballyshannon South Ballyshannon / Bundoran Agnes Lawless 071 983 4000 [email protected] South Donegal Town Marion Gallagher 074 974 0692 [email protected] Temporary meeting organisation South Killybegs by Agnes Lawless, Ballyshannon PCTAdminTypeContactsV1.2_30July2013.xls Donegal Primary Care Team Facilitators Network Area PCT Facilitator Address Email Phone Mobile Fax South Donegal Ballyshannon/Bundoran Ms Sandra Sheerin Iona Office Block [email protected] 071 983 4000 087 9682067 071 9834009 Killybegs/Glencolmkille Upper Main Street Ardara/Glenties Ballyshannon Donegal Town Areas East Donegal Finn Valley, Lagan Valley, Mr Peter Walker Social Inclusion Dept., First [email protected] 074 910 4427 087 1229603 & Lifford/Castlefin areas Floor, County Clinic, St. -

Chvrches the Bones of What You Believe Mp3, Flac, Wma

Chvrches The Bones Of What You Believe mp3, flac, wma DOWNLOAD LINKS (Clickable) Genre: Electronic / Pop Album: The Bones Of What You Believe Country: Canada Released: 2013 Style: Indie Pop, Synth-pop MP3 version RAR size: 1669 mb FLAC version RAR size: 1381 mb WMA version RAR size: 1553 mb Rating: 4.5 Votes: 488 Other Formats: DTS ADX DXD MP4 VOC MOD RA Tracklist I The Mother We Share 3:12 II We Sink 3:34 III Gun 3:54 IV Tether 4:46 V Lies 3:41 VI Under The Tide 4:32 VII Recover 3:46 VIII Night Sky 3:51 IX Science/Visions 3:58 X Lungs 3:03 XI By The Throat 4:09 XII You Caught The Light 5:38 Companies, etc. Recorded At – Alucard Studios Mixed At – Eldorado Recording Studios Mixed At – Wall 2 Wall Recording Mastered At – Gateway Mastering Manufactured By – Universal Music Canada Inc. Distributed By – Universal Music Canada Inc. Credits Design – Amy Burrows Drums – Jonny Scott (tracks: III, VIII) Engineer [Pro Tools] – Chris Kasych (tracks: I to III, V to X, XII), Martin Cooke (tracks: I to III, V to X, XII) Mastered By – Bob Ludwig Mixed By – Chvrches (tracks: IV, XI), Rich Costey (tracks: I to III, V to X, XII) Mixed By [Assistant] – Bo Hill (tracks: I to III, V to X, XII), Eric Isip (tracks: I to III, V to X, XII) Performer [Chvrches Are] – Iain Cook, Lauren Mayberry, Martin Doherty Written-By, Producer – Chvrches Notes Mixed by Rich Costey at Eldorado Recording Studios, Los Angeles Pro Tools Engineers: Chris Kasych & Martin Cooke Mix Assistants: Bo Hill & Eric Isip Except Tether and By The Throat mixed by Chvrches at Wall 2 Wall Studios, Chicago ℗&© 2013 Chvrches under exclusive license to Glassnote Entertainment Group LLC. -

Irish Landscape Names

Irish Landscape Names Preface to 2010 edition Stradbally on its own denotes a parish and village); there is usually no equivalent word in the Irish form, such as sliabh or cnoc; and the Ordnance The following document is extracted from the database used to prepare the list Survey forms have not gained currency locally or amongst hill-walkers. The of peaks included on the „Summits‟ section and other sections at second group of exceptions concerns hills for which there was substantial www.mountainviews.ie The document comprises the name data and key evidence from alternative authoritative sources for a name other than the one geographical data for each peak listed on the website as of May 2010, with shown on OS maps, e.g. Croaghonagh / Cruach Eoghanach in Co. Donegal, some minor changes and omissions. The geographical data on the website is marked on the Discovery map as Barnesmore, or Slievetrue in Co. Antrim, more comprehensive. marked on the Discoverer map as Carn Hill. In some of these cases, the evidence for overriding the map forms comes from other Ordnance Survey The data was collated over a number of years by a team of volunteer sources, such as the Ordnance Survey Memoirs. It should be emphasised that contributors to the website. The list in use started with the 2000ft list of Rev. these exceptions represent only a very small percentage of the names listed Vandeleur (1950s), the 600m list based on this by Joss Lynam (1970s) and the and that the forms used by the Placenames Branch and/or OSI/OSNI are 400 and 500m lists of Michael Dewey and Myrddyn Phillips. -

Irish Rare Bird Report 2011 2011 Irish Rare Bird Report IRBC Introduction

Tom Shevlin Tom 2011 13th November Wicklow. Head, Co. Desert Bray Wheatear, Irish Rare Bird Report 2011 2011 Irish Rare Bird Report IRBC Introduction From 2000 to 2010, twenty-two species were added to the Irish list - an average of two per year, and 2011 maintained that average. The two species added were a White-winged Scoter Melanitta deglandi stejnegeri (Kerry) in March that subsequently transpired to have been present since February and a Pallid Harrier Circus macrourus (Cork) in April. The latter species became one of the signature birds of 2011 as an autumn influx also provided the second to fifth records (Wexford, Galway and Cork). The second Semipalmated Plover Charadrius semipalmatus (Kerry) and third Hudsonian Whimbrel Numenius hudsonicus (Cork) were found in September. The fourth Great Reed Warbler Acrocephalus arundinaceus (Wexford) was found in May and a Red-necked Stint Calidris ruficollis (Kerry), also the fourth for Ireland, in August. An influx of four Desert Wheatear Oenanthe deserti (Wicklow, Dublin and Waterford) provided the fifth to eighth records. Rare sub-species recorded during the year included the third Northern Harrier Circus cyaneus hudsonius (Wexford) in October. The report also contains details of some headline rarities from earlier years. A record of Pacific Diver Gavia pacifica (Galway) in January 2009 becomes the first record for Ireland and is considered likely to have involved the same individual subsequently found nearby in 2010 (Irish Birds 9: 288). Two records of Blyth’s Reed Warbler Acrocephalus dumetorum, in October 2009 (Mayo) and October 2010 (Cork), were the fourth and fifth records. Also recorded for the fifth time were an Arctic Redpoll Carduelis hornemanni (Mayo) in May 2008, a Solitary Sandpiper Tringa solitaria (Mayo) and Marsh Warbler Acrocephalus palustris (Cork) in September 2009 and a Yellow-breasted Bunting Emberiza aureola (Cork) in October 2010. -

This Announcement Contains Inside Information for the Purposes Of

RNS Number : 8738R Esken Limited 11 March 2021 This announcement contains inside information for the purposes of article 7 of the Market Abuse Regulation (EU) 596/2014 as it forms part of domestic law by virtue of the European Union (Withdrawal) Act 2018. 11 March 2021 Esken Limited ("Esken" or "the Group") Trading update Esken, the aviation and energy infrastructure group, issues the following update on trading for the year to 28 February 2021. Summary • Strict financial discipline has resulted in £77.4m of cash and undrawn bank facilities available as at 28 February. • London Southend Airport benefited from continued activity through its global logistics operation. • Gate fees at Stobart Energy have continued to improve toward pre-COVID-19 levels. • Esken is progressing a range of options regarding Stobart Air & Propius and expects to bring the matter to conclusion in the near term. David Shearer, Executive Chairman said, "We have continued to deliver against the strategy we set out at the time of our capital raise in June 2020 despite the business interruption caused by COVID-19 extending far beyond all reasonable expectations at that time." "Esken is becoming a more focused business. We divested the Rail & Civils division and remain committed to exiting Stobart Air and Propius. As a Board, we are undertaking a review of our strategic options in light of the impact of the pandemic. We are doing this to ensure that we protect the capability of our core operations and focus on delivering value for shareholders." "We continue to maintain strict financial discipline. This has allowed us to minimise cash burn and protect our liquidity position.