Chapter 1 Euclidean Space

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Parallelogram Law Objective: to Take Students Through the Process

The Parallelogram Law Objective: To take students through the process of discovery, making a conjecture, further exploration, and finally proof. I. Introduction: Use one of the following… • Geometer’s Sketchpad demonstration • Geogebra demonstration • The introductory handout from this lesson Using one of the introductory activities, allow students to explore and make a conjecture about the relationship between the sum of the squares of the sides of a parallelogram and the sum of the squares of the diagonals. Conjecture: The sum of the squares of the sides of a parallelogram equals the sum of the squares of the diagonals. Ask the question: Can we prove this is always true? II. Activity: Have students look at one more example. Follow the instructions on the exploration handouts, “Demonstrating the Parallelogram Law.” • Give each student a copy of the student handouts, scissors, a glue stick, and two different colored highlighters. Have students follow the instructions. When they get toward the end, they will need to cut very small pieces to fit in the uncovered space. Most likely there will be a very small amount of space left uncovered, or a small amount will extend outside the figure. • After the activity, discuss the results. Did the squares along the two diagonals fit into the squares along all four sides? Since it is unlikely that it will fit exactly, students might question if the relationship is always true. At this point, talk about how we will need to find a convincing proof. III. Go through one or more of the proofs below: Page 1 of 10 MCC@WCCUSD 02/26/13 A. -

Kernelization of the Subset General Position Problem in Geometry Jean-Daniel Boissonnat, Kunal Dutta, Arijit Ghosh, Sudeshna Kolay

Kernelization of the Subset General Position problem in Geometry Jean-Daniel Boissonnat, Kunal Dutta, Arijit Ghosh, Sudeshna Kolay To cite this version: Jean-Daniel Boissonnat, Kunal Dutta, Arijit Ghosh, Sudeshna Kolay. Kernelization of the Subset General Position problem in Geometry. MFCS 2017 - 42nd International Symposium on Mathematical Foundations of Computer Science, Aug 2017, Alborg, Denmark. 10.4230/LIPIcs.MFCS.2017.25. hal-01583101 HAL Id: hal-01583101 https://hal.inria.fr/hal-01583101 Submitted on 6 Sep 2017 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Kernelization of the Subset General Position problem in Geometry Jean-Daniel Boissonnat1, Kunal Dutta1, Arijit Ghosh2, and Sudeshna Kolay3 1 INRIA Sophia Antipolis - Méditerranée, France 2 Indian Statistical Institute, Kolkata, India 3 Eindhoven University of Technology, Netherlands. Abstract In this paper, we consider variants of the Geometric Subset General Position problem. In defining this problem, a geometric subsystem is specified, like a subsystem of lines, hyperplanes or spheres. The input of the problem is a set of n points in Rd and a positive integer k. The objective is to find a subset of at least k input points such that this subset is in general position with respect to the specified subsystem. -

Chapter 11. Three Dimensional Analytic Geometry and Vectors

Chapter 11. Three dimensional analytic geometry and vectors. Section 11.5 Quadric surfaces. Curves in R2 : x2 y2 ellipse + =1 a2 b2 x2 y2 hyperbola − =1 a2 b2 parabola y = ax2 or x = by2 A quadric surface is the graph of a second degree equation in three variables. The most general such equation is Ax2 + By2 + Cz2 + Dxy + Exz + F yz + Gx + Hy + Iz + J =0, where A, B, C, ..., J are constants. By translation and rotation the equation can be brought into one of two standard forms Ax2 + By2 + Cz2 + J =0 or Ax2 + By2 + Iz =0 In order to sketch the graph of a quadric surface, it is useful to determine the curves of intersection of the surface with planes parallel to the coordinate planes. These curves are called traces of the surface. Ellipsoids The quadric surface with equation x2 y2 z2 + + =1 a2 b2 c2 is called an ellipsoid because all of its traces are ellipses. 2 1 x y 3 2 1 z ±1 ±2 ±3 ±1 ±2 The six intercepts of the ellipsoid are (±a, 0, 0), (0, ±b, 0), and (0, 0, ±c) and the ellipsoid lies in the box |x| ≤ a, |y| ≤ b, |z| ≤ c Since the ellipsoid involves only even powers of x, y, and z, the ellipsoid is symmetric with respect to each coordinate plane. Example 1. Find the traces of the surface 4x2 +9y2 + 36z2 = 36 1 in the planes x = k, y = k, and z = k. Identify the surface and sketch it. Hyperboloids Hyperboloid of one sheet. The quadric surface with equations x2 y2 z2 1. -

An Introduction to Topology the Classification Theorem for Surfaces by E

An Introduction to Topology An Introduction to Topology The Classification theorem for Surfaces By E. C. Zeeman Introduction. The classification theorem is a beautiful example of geometric topology. Although it was discovered in the last century*, yet it manages to convey the spirit of present day research. The proof that we give here is elementary, and its is hoped more intuitive than that found in most textbooks, but in none the less rigorous. It is designed for readers who have never done any topology before. It is the sort of mathematics that could be taught in schools both to foster geometric intuition, and to counteract the present day alarming tendency to drop geometry. It is profound, and yet preserves a sense of fun. In Appendix 1 we explain how a deeper result can be proved if one has available the more sophisticated tools of analytic topology and algebraic topology. Examples. Before starting the theorem let us look at a few examples of surfaces. In any branch of mathematics it is always a good thing to start with examples, because they are the source of our intuition. All the following pictures are of surfaces in 3-dimensions. In example 1 by the word “sphere” we mean just the surface of the sphere, and not the inside. In fact in all the examples we mean just the surface and not the solid inside. 1. Sphere. 2. Torus (or inner tube). 3. Knotted torus. 4. Sphere with knotted torus bored through it. * Zeeman wrote this article in the mid-twentieth century. 1 An Introduction to Topology 5. -

CHAPTER 3. VECTOR ALGEBRA Part 1: Addition and Scalar

CHAPTER 3. VECTOR ALGEBRA Part 1: Addition and Scalar Multiplication for Vectors. §1. Basics. Geometric or physical quantities such as length, area, volume, tempera- ture, pressure, speed, energy, capacity etc. are given by specifying a single numbers. Such quantities are called scalars, because many of them can be measured by tools with scales. Simply put, a scalar is just a number. Quantities such as force, velocity, acceleration, momentum, angular velocity, electric or magnetic field at a point etc are vector quantities, which are represented by an arrow. If the ‘base’ and the ‘head’ of this arrow are B and H repectively, then we denote this vector by −−→BH: Figure 1. Often we use a single block letter in lower case, such as u, v, w, p, q, r etc. to denote a vector. Thus, if we also use v to denote the above vector −−→BH, then v = −−→BH.A vector v has two ingradients: magnitude and direction. The magnitude is the length of the arrow representing v, and is denoted by v . In case v = −−→BH, certainly we | | have v = −−→BH for the magnitude of v. The meaning of the direction of a vector is | | | | self–evident. Two vectors are considered to be equal if they have the same magnitude and direction. You recognize two equal vectors in drawing, if their representing arrows are parallel to each other, pointing in the same way, and have the same length 1 Figure 2. For example, if A, B, C, D are vertices of a parallelogram, followed in that order, then −→AB = −−→DC and −−→AD = −−→BC: Figure 3. -

Variables in Mathematics Education

Variables in Mathematics Education Susanna S. Epp DePaul University, Department of Mathematical Sciences, Chicago, IL 60614, USA http://www.springer.com/lncs Abstract. This paper suggests that consistently referring to variables as placeholders is an effective countermeasure for addressing a number of the difficulties students’ encounter in learning mathematics. The sug- gestion is supported by examples discussing ways in which variables are used to express unknown quantities, define functions and express other universal statements, and serve as generic elements in mathematical dis- course. In addition, making greater use of the term “dummy variable” and phrasing statements both with and without variables may help stu- dents avoid mistakes that result from misinterpreting the scope of a bound variable. Keywords: variable, bound variable, mathematics education, placeholder. 1 Introduction Variables are of critical importance in mathematics. For instance, Felix Klein wrote in 1908 that “one may well declare that real mathematics begins with operations with letters,”[3] and Alfred Tarski wrote in 1941 that “the invention of variables constitutes a turning point in the history of mathematics.”[5] In 1911, A. N. Whitehead expressly linked the concepts of variables and quantification to their expressions in informal English when he wrote: “The ideas of ‘any’ and ‘some’ are introduced to algebra by the use of letters. it was not till within the last few years that it has been realized how fundamental any and some are to the very nature of mathematics.”[6] There is a question, however, about how to describe the use of variables in mathematics instruction and even what word to use for them. -

Homology Stratifications and Intersection Homology 1 Introduction

ISSN 1464-8997 (on line) 1464-8989 (printed) 455 Geometry & Topology Monographs Volume 2: Proceedings of the Kirbyfest Pages 455–472 Homology stratifications and intersection homology Colin Rourke Brian Sanderson Abstract A homology stratification is a filtered space with local ho- mology groups constant on strata. Despite being used by Goresky and MacPherson [3] in their proof of topological invariance of intersection ho- mology, homology stratifications do not appear to have been studied in any detail and their properties remain obscure. Here we use them to present a simplified version of the Goresky–MacPherson proof valid for PL spaces, and we ask a number of questions. The proof uses a new technique, homology general position, which sheds light on the (open) problem of defining generalised intersection homology. AMS Classification 55N33, 57Q25, 57Q65; 18G35, 18G60, 54E20, 55N10, 57N80, 57P05 Keywords Permutation homology, intersection homology, homology stratification, homology general position Rob Kirby has been a great source of encouragement. His help in founding the new electronic journal Geometry & Topology has been invaluable. It is a great pleasure to dedicate this paper to him. 1 Introduction Homology stratifications are filtered spaces with local homology groups constant on strata; they include stratified sets as special cases. Despite being used by Goresky and MacPherson [3] in their proof of topological invariance of intersec- tion homology, they do not appear to have been studied in any detail and their properties remain obscure. It is the purpose of this paper is to publicise these neglected but powerful tools. The main result is that the intersection homology groups of a PL homology stratification are given by singular cycles meeting the strata with appropriate dimension restrictions. -

1 Lifts of Polytopes

Lecture 5: Lifts of polytopes and non-negative rank CSE 599S: Entropy optimality, Winter 2016 Instructor: James R. Lee Last updated: January 24, 2016 1 Lifts of polytopes 1.1 Polytopes and inequalities Recall that the convex hull of a subset X n is defined by ⊆ conv X λx + 1 λ x0 : x; x0 X; λ 0; 1 : ( ) f ( − ) 2 2 [ ]g A d-dimensional convex polytope P d is the convex hull of a finite set of points in d: ⊆ P conv x1;:::; xk (f g) d for some x1;:::; xk . 2 Every polytope has a dual representation: It is a closed and bounded set defined by a family of linear inequalities P x d : Ax 6 b f 2 g for some matrix A m d. 2 × Let us define a measure of complexity for P: Define γ P to be the smallest number m such that for some C s d ; y s ; A m d ; b m, we have ( ) 2 × 2 2 × 2 P x d : Cx y and Ax 6 b : f 2 g In other words, this is the minimum number of inequalities needed to describe P. If P is full- dimensional, then this is precisely the number of facets of P (a facet is a maximal proper face of P). Thinking of γ P as a measure of complexity makes sense from the point of view of optimization: Interior point( methods) can efficiently optimize linear functions over P (to arbitrary accuracy) in time that is polynomial in γ P . ( ) 1.2 Lifts of polytopes Many simple polytopes require a large number of inequalities to describe. -

Interval Notation and Linear Inequalities

CHAPTER 1 Introductory Information and Review Section 1.7: Interval Notation and Linear Inequalities Linear Inequalities Linear Inequalities Rules for Solving Inequalities: 86 University of Houston Department of Mathematics SECTION 1.7 Interval Notation and Linear Inequalities Interval Notation: Example: Solution: MATH 1300 Fundamentals of Mathematics 87 CHAPTER 1 Introductory Information and Review Example: Solution: Example: 88 University of Houston Department of Mathematics SECTION 1.7 Interval Notation and Linear Inequalities Solution: Additional Example 1: Solution: MATH 1300 Fundamentals of Mathematics 89 CHAPTER 1 Introductory Information and Review Additional Example 2: Solution: 90 University of Houston Department of Mathematics SECTION 1.7 Interval Notation and Linear Inequalities Additional Example 3: Solution: Additional Example 4: Solution: MATH 1300 Fundamentals of Mathematics 91 CHAPTER 1 Introductory Information and Review Additional Example 5: Solution: Additional Example 6: Solution: 92 University of Houston Department of Mathematics SECTION 1.7 Interval Notation and Linear Inequalities Additional Example 7: Solution: MATH 1300 Fundamentals of Mathematics 93 Exercise Set 1.7: Interval Notation and Linear Inequalities For each of the following inequalities: Write each of the following inequalities in interval (a) Write the inequality algebraically. notation. (b) Graph the inequality on the real number line. (c) Write the inequality in interval notation. 23. 1. x is greater than 5. 2. x is less than 4. 24. 3. x is less than or equal to 3. 4. x is greater than or equal to 7. 25. 5. x is not equal to 2. 6. x is not equal to 5 . 26. 7. x is less than 1. 8. -

Holley GM LS Race Single-Plane Intake Manifold Kits

Holley GM LS Race Single-Plane Intake Manifold Kits 300-255 / 300-255BK LS1/2/6 Port-EFI - w/ Fuel Rails 4150 Flange 300-256 / 300-256BK LS1/2/6 Carbureted/TB EFI 4150 Flange 300-290 / 300-290BK LS3/L92 Port-EFI - w/ Fuel Rails 4150 Flange 300-291 / 300-291BK LS3/L92 Carbureted/TB EFI 4150 Flange 300-294 / 300-294BK LS1/2/6 Port-EFI - w/ Fuel Rails 4500 Flange 300-295 / 300-295BK LS1/2/6 Carbureted/TB EFI 4500 Flange IMPORTANT: Before installation, please read these instructions completely. APPLICATIONS: The Holley LS Race single-plane intake manifolds are designed for GM LS Gen III and IV engines, utilized in numerous performance applications, and are intended for carbureted, throttle body EFI, or direct-port EFI setups. The LS Race single-plane intake manifolds are designed for hi-performance/racing engine applications, 5.3 to 6.2+ liter displacement, and maximum engine speeds of 6000-7000 rpm, depending on the engine combination. This single-plane design provides optimal performance across the RPM spectrum while providing maximum performance up to 7000 rpm. These intake manifolds are for use on non-emissions controlled applications only, and will not accept stock components and hardware. Port EFI versions may not be compatible with all throttle body linkages. When installing the throttle body, make certain there is a minimum of ¼” clearance between all linkage and the fuel rail. SPLIT DESIGN: The Holley LS Race manifold incorporates a split feature, which allows disassembly of the intake for direct access to internal plenum and port surfaces, making custom porting and matching a snap. -

Simplicial Complexes

46 III Complexes III.1 Simplicial Complexes There are many ways to represent a topological space, one being a collection of simplices that are glued to each other in a structured manner. Such a collection can easily grow large but all its elements are simple. This is not so convenient for hand-calculations but close to ideal for computer implementations. In this book, we use simplicial complexes as the primary representation of topology. Rd k Simplices. Let u0; u1; : : : ; uk be points in . A point x = i=0 λiui is an affine combination of the ui if the λi sum to 1. The affine hull is the set of affine combinations. It is a k-plane if the k + 1 points are affinely Pindependent by which we mean that any two affine combinations, x = λiui and y = µiui, are the same iff λi = µi for all i. The k + 1 points are affinely independent iff P d P the k vectors ui − u0, for 1 ≤ i ≤ k, are linearly independent. In R we can have at most d linearly independent vectors and therefore at most d+1 affinely independent points. An affine combination x = λiui is a convex combination if all λi are non- negative. The convex hull is the set of convex combinations. A k-simplex is the P convex hull of k + 1 affinely independent points, σ = conv fu0; u1; : : : ; ukg. We sometimes say the ui span σ. Its dimension is dim σ = k. We use special names of the first few dimensions, vertex for 0-simplex, edge for 1-simplex, triangle for 2-simplex, and tetrahedron for 3-simplex; see Figure III.1. -

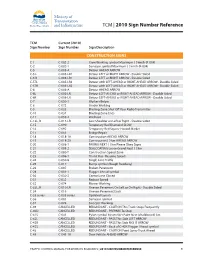

2010 Sign Number Reference for Traffic Control Manual

TCM | 2010 Sign Number Reference TCM Current (2010) Sign Number Sign Number Sign Description CONSTRUCTION SIGNS C-1 C-002-2 Crew Working symbol Maximum ( ) km/h (R-004) C-2 C-002-1 Surveyor symbol Maximum ( ) km/h (R-004) C-5 C-005-A Detour AHEAD ARROW C-5 L C-005-LR1 Detour LEFT or RIGHT ARROW - Double Sided C-5 R C-005-LR1 Detour LEFT or RIGHT ARROW - Double Sided C-5TL C-005-LR2 Detour with LEFT-AHEAD or RIGHT-AHEAD ARROW - Double Sided C-5TR C-005-LR2 Detour with LEFT-AHEAD or RIGHT-AHEAD ARROW - Double Sided C-6 C-006-A Detour AHEAD ARROW C-6L C-006-LR Detour LEFT-AHEAD or RIGHT-AHEAD ARROW - Double Sided C-6R C-006-LR Detour LEFT-AHEAD or RIGHT-AHEAD ARROW - Double Sided C-7 C-050-1 Workers Below C-8 C-072 Grader Working C-9 C-033 Blasting Zone Shut Off Your Radio Transmitter C-10 C-034 Blasting Zone Ends C-11 C-059-2 Washout C-13L, R C-013-LR Low Shoulder on Left or Right - Double Sided C-15 C-090 Temporary Red Diamond SLOW C-16 C-092 Temporary Red Square Hazard Marker C-17 C-051 Bridge Repair C-18 C-018-1A Construction AHEAD ARROW C-19 C-018-2A Construction ( ) km AHEAD ARROW C-20 C-008-1 PAVING NEXT ( ) km Please Obey Signs C-21 C-008-2 SEALCOATING Loose Gravel Next ( ) km C-22 C-080-T Construction Speed Zone C-23 C-086-1 Thank You - Resume Speed C-24 C-030-8 Single Lane Traffic C-25 C-017 Bump symbol (Rough Roadway) C-26 C-007 Broken Pavement C-28 C-001-1 Flagger Ahead symbol C-30 C-030-2 Centre Lane Closed C-31 C-032 Reduce Speed C-32 C-074 Mower Working C-33L, R C-010-LR Uneven Pavement On Left or On Right - Double Sided C-34