LPS81 Nov 10.Pub

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Delegated Decisions

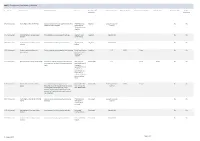

ARTICLE NO: 1A PLANNING COMMITTEE MEMBERS UPDATE 2020/21 Issue: 4 Article of: Corporate Director of Place & Community Contact for further information: Mrs C Thomas (Extn. 5134) (E-mail: [email protected]) SUBJECT: Applications Determined Under The Delegated System – 30/05/2020 to 10/07/2020 WARD:- Aughton And Downholland Application: 2016/0977/PNP Decision: Withdrawn Proposal: Application for Determination as to Whether Prior Approval is Required for Details - Agricultural access track. Location: Home Farm, Back Lane, Aughton, Ormskirk, Lancashire, L39 6SX Applicant: Aughton Pig Producers Ltd WARD:- Aughton And Downholland Application: 2019/1306/FUL Decision: Planning Permission Granted Proposal: Formation of car park following demolition of outbuildings. Location: Land To The Rear Of, 69 - 75 Town Green Lane, Aughton, Lancashire, Applicant: Mr I Mercer WARD:- Aughton And Downholland Application: 2020/0117/FUL Decision: Planning Permission Granted Proposal: Erection of a stable building with tack room and the formation of a menage for the keeping of horses along with improvements to the existing site access onto Lord Sefton Way including new gates and a splayed wall entrance. Location: The Old Vicarage, 1 Lord Sefton Way, Great Altcar, Liverpool, Lancashire, L37 5AA Applicant: Mr & Mrs Neary WARD:- Aughton And Downholland Application: 2020/0308/FUL Decision: Planning Permission Granted Proposal: Single storey side extension including infill extension to existing carport and internal/external alterations. Location: 106 Brookfield Lane, Aughton, Ormskirk, Lancashire, L39 6SP Applicant: Mr Steve Carter WARD:- Aughton And Downholland Application: 2020/0333/FUL Decision: Planning Permission Granted Proposal: Installation of a 21kW ground source heat pump providing heat and hot water for Home Farm and an existing agricultural building (retrospective). -

Report Of: Executive Manager Community Services

AGENDA ITEM: 6/16 CABINET: 15 June 2010 Report of: Executive Manager Community Services Relevant Portfolio Holder: Councillor A Fowler Contact for further information: Mr S Kent (Extn. 5169) (E-mail: [email protected]) SUBJECT: USE OF SECTION 106 MONIES IN BANKS, HESKETH BANK AND WRIGHTINGTON Wards affected: North Meols, Hesketh with Becconsall, Wrightington 1.0 PURPOSE OF THE REPORT 1.1 To consider requests from North Meols, Hesketh with Becconsall, and Wrightington Parish Councils regarding the use of monies received by the Borough Council from housing developers for the enhancement of public open space and recreation provision in their Parishes. 2.0 RECOMMENDATIONS TO CABINET 2.1 That the projects detailed in section 6 of this report be approved and the Section 106 sums of £104,510 for North Meols, £93,250 for Hesketh with Becconsall ( £29,400 from available funds and £63,850 when available from funds due), and £81,710 for Wrightington be made available to the respective Parish Councils for their projects. 2.2 That the commuted sums be paid to the respective Parish Councils subject to them entering into suitable legal agreements with the Council. 3.0 BACKGROUND 3.1 Members will recall that under policy LE.13 of the local plan developers must provide open space facilities as part of housing developments. Where developments are less than 20 dwellings or on sites where it is nor reasonable to expect a developer to provide on-site facilities, and where there is a deficiency of open space, the Council can require a commuted sum for the provision and maintenance of improvements to nearby open space or for the creation of new leisure related facilities in the area. -

A NORTH MEOLS DOCUMENT of 1716. R I ^HE Document Here

A NORTH MEOLS DOCUMENT OF 1716. By F. H. Cheetham, F.S.A. r I ^HE document here printed was till lately in the old A Town's chest, at the parish church of St. Cuthbert, North Meols (Churchtown, Southport), but with other township papers was in February, 1931, transferred to the custody of the Southport Corporation, and is now at the Southport Town Hall. It is written on the first page of a sheet of paper folded into two leaves of 12 by 8 inches. The outer edge of the first leaf is slightly broken, and some of the words are therefore imperfect, but they are easily read and are here restored in italics. The document, as will be seen, is addressed to the Inhabitants of the Parish of North Meols, and conveys to them the decision of five Deputy Lieutenants of the County of Lancaster in the matter of a dispute, or differ ence, between the Townships of North Meols and Birk- dale (which together constituted the Parish cf North Meols) touching their respective shares in the payment of the Militia Tax levied on the parish by the County. For County purposes the parish was the unit of local government, but in respect to its own affairs each town ship was governed by its Vestry and nominated its own officers. The two North Meols Townships differed con siderably in extent and population, the area of North Meols being 8,467 acres, and that of Birkdale 2,214 acres. 1 The population in 1716 can only be conjectured, 1 V.C.H. -

The History of Tarleton & Hesketh Bank and Their Maritime Past

The History of Tarleton & Hesketh Bank and their Maritime Past “We Built This Village on Rock’n’Coal” By David Edmondson A version of this book is accessible on-line at http://www.heskethbank.com/history.html It is intended that the on-line version will be amended and updated as further information on the villages’ history emerges The author can be contacted on: [email protected] 1 Index Dedication Preface Introduction Geography & General History of Tarleton and Hesketh Bank Time line Village photographs Tarleton & Hesketh Bank Population – Names and Numbers Population Infant mortality, life expectancy, and Causes of Death Surnames Occupations What did Village People Look Like and Sound Like? Influences on the Maritime Economy Roads Rivers Canals Railways Cargos on the Ribble-Douglas-Canal waterway Sailing Ships Built at Tarleton and Hesketh Bank Historical Background List of Ships Built at Tarleton and Hesketh Bank Boatmen, Sailors and Mariners List of Identified Mariners of Tarleton and Hesketh Bank Ship Owners List of Ships with Owners from Tarleton and Hesketh Bank Summary A Bonus: Oddments Collected along the Way: Crime, Religion, Mayors of Tarleton, Types of Sailing Ships, Reading Old Handwriting, Local Dialect, Chelsea Pensioner, Col. Banastre Tarleton Further Sources to be Explored 2 This book is dedicated to my father: John Henry Edmondson 1914-1999 He was born in Tarleton and died in Tarleton. In between he was postman to the villages of Tarleton and Hesketh Bank for 32 years, and was Clerk to Tarleton Parish Council for 48 years. He knew the villages well and was well known in the villages. -

H. S. of L. and C-, Vol. Xlvh. Douglas Chapcl, Parbold

XLVH. VOL. C-, AND L. OF S. H. PARBOLD. CHAPCL, DOUGLAS SOME HISTORICAL NOTES ON THE CHAPEL OF OUR BLESSED LADY, PARBOLD, LANCASHIRE. By William Frederick Price. Read 5th December, 1895. HIS ancient and interesting ecclesiastical T edifice, better known as " Douglas Chapel," was demolished in 1878. It was situated at the foot of Parbokl Hill, in the township of Parbokl, and lay hidden in a picturesque and sequestered valley. Parbokl Hill, with its extensive stone quarries, is a familiar object to travellers on the Lancashire and Yorkshire Railway between Southport and \Vigan. It is the most prominent feature of a range consisting of Parbokl, Hunters, and Harrock Hills ; and on the opposite side of the valley is another range, comprising Ashurst, Upholland, and Billinge. Parbokl and Ashurst Hills stand like sentinels at the neck of a beautiful and well- timbered valley, which is watered by the River Douglas, 1 a sluggish stream, with high banks, veiled with alder, willows, and poplar. This river 1 A Celtic river-name. The word "dhu," black, appears in five rivers in Wales, three in Scotland, and one in Dorset, which are called Dulas. There are also two in Scotland and one in Lancashire called the Douglas ; and we have the Dcjulas in Radnor, the Dowles in Shropshire, and the Higgles in Lancashire. Rev. I. Taylor, Words ami Places, p. 143. 208 Historical Notes on Douglas Chapel. takes its source among the hills of Rivington, flows through the town of Wigan, 2 past Gathurst, Appley Bridge, Parbold, Ruftbrd, and Tarleton, and joins the Kibble estuary at Hesketh Bank. -

![(Ainsdale): (Revised 10/4/98 [Vide Also Rimmer, North Meols]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/0662/ainsdale-revised-10-4-98-vide-also-rimmer-north-meols-1070662.webp)

(Ainsdale): (Revised 10/4/98 [Vide Also Rimmer, North Meols]

RIMMER of AINSDALE On 27 September 1758 at Formby chapel (Walton parish, south-west Lancashire) John Rymer an 18- year-old yeoman of the adjacent coastal parish of North Meols and son of Thomas Rymer the miller of Churchtown (North Meols) married by licence Elizabeth Rymer, daughter of Thomas Rymer of Ainsdale mill house (in Formby chapelry): the witnesses were John Sumner and Richard Rymer.1 It seems clear that that Elizabeth Rymer was a daughter of Thomas and Alice Rymer, baptised at Formby on 23 December 1739. Elizabeth’s descent is part of the complicated story of the Ainsdale Rymer/Rimmer families: her descent cannot be traced with precision beyond her father, but it is a rich field for further work. The name Rimmer is an occupational one meaning ‘rhymer’ or poet and became particularly common in south-west Lancashire from an early period: in Formby and North Meols its occurrence was frequent to an extraordinary degree and led to nicknames being added to the name to make identification possible. The spellings Rymer/Rimer/Rimmer and Rimmer were all absolutely interchangeble and the variations are not to be seen as significant in any way. As elsewhere in this work the surname has usually been spelled according to the variation used in the source being quoted.2 Beginnings The search for Thomas Rimmer’s origins has to turn first to all the known Rimmers connected with Ainsdale mill prior to his occupation in c. 1734 and then to others elsewhere in Ainsdale. Early Ainsdale millers The mill house at Ainsdale lay in the far north-east corner of the township on the boundaries of Birkdale (North Meols) and Downholland (Halsall). -

LALC Constitution

LANCASHIRE ASSOCIATION OF LOCAL COUNCILS Howick House, Howick Park Ave, Penwortham, Preston, PR1 0LS Telephone 01772 750900 E-mail [email protected] CONSTITUTION Note : All references to Local Councils means parish councils, town councils, community councils, neighbourhood councils, village councils and parish meetings. All references to serving councillors in member parishes means parish councils, town councils, community councils neighbourhood councils, village councils and parish meetings. Clause l Name and Membership The Association shall consist of Local Councils in the County of Lancashire, Blackburn with Darwen and in the Metropolitan Districts of Bolton, Bury, Oldham, Rochdale, Salford, Wigan, Knowsley, St Helens, Sefton, Tameside, and Manchester City and shall be known as the Lancashire Association of Local Councils (LALC). By virtue of membership of the County Association, councils have membership of the National Association of Local Councils (NALC). Clause 2 Objectives The aims and objectives of the Association are to take all such steps as may be necessary or desirable in the interest of councils consistent with the objectives of the National Association of Local Councils which are: (a) To protect and represent the interests, rights, functions, and privileges of member councils (b) To assist members in the performance of their duties and to promote and develop the social cultural and recreational wellbeing of their local areas (c) To promote a widespread and well-informed interest in local councils (d) To promote good practice in local councils. (e) To promote high standards through good quality training Clause 3 Annual General Meeting (a) There shall be an Annual General meeting of the County Association. -

Parish Council Date Comment Wrightington (Yes – No Suggestions

Parish Council Date Comment Wrightington 27/6/06 – letter The Council would like to thank you for the ACSeS Parish Toolkit which appears to be most useful. (Yes – no suggestions) With regard to the provision of Training the Parish Council are of the opinion that this could prove very useful however, it would depend upon the cost implications for the Parish Council and the level of commitment required from Councillors as it can prove difficult for those with full time jobs and families to commit themselves. The Council look forward to more detailed information in relation to this suggestion in due course. Hesketh with Becconsall 4/7/06 – email This Council considered your letter regarding the above at their July meeting. (No) The Council has however opted to arrange such training, within the Parish, through the ‘Lancashire Training Partnership’ which all Councillors have signified they will attend. I would comment that your letter did concentrate the minds of Councillors on the need for training, something I have struggled with since being appointed. Bickerstaffe July 2006 – phone call Arthur Gore rang, he had received the Toolkit in the post. (No) With regards to training he will be attending a meeting on Monday and will pass the information on. He is also attending a Local Government Admin Course, which covers most of the training in the Toolkit, which he mentioned was very helpful. Further phone call 2/8/06 Constitutional training not required. Aughton 18/8/2006? At our last Parish Council Meeting held earlier this week, it was felt that some training would be helpful for members particularly if it was offered in the same form (Yes – similar format to as the annual Seminar at Edge Hill College for Code of Conduct training. -

2001 No. 2432 LOCAL GOVERNMENT, ENGLAND The

STATUTORY INSTRUMENTS 2001 No. 2432 LOCAL GOVERNMENT, ENGLAND The District of West Lancashire (Electoral Changes) Order 2001 Made ----- 3rdJuly 2001 Coming into force in accordance with article 1(2), (3) and (4) Whereas the Local Government Commission for England, acting pursuant to section 15(4) of the Local Government Act 1992(a), has submitted to the Secretary of State a report dated September 2000 on its review of the district of West Lancashire together with its recommendations: And whereas the Secretary of State has decided to give effect, with modifications, to those recommendations: Now, therefore, the Secretary of State, in exercise of the powers conferred on him by sections 17(b) and 26 of the Local Government Act 1992, and of all other powers enabling him in that behalf, hereby makes the following Order: Citation, commencement and interpretation 1.—(1) This Order may be cited as the District of West Lancashire (Electoral Changes) Order 2001. (2) This article and articles 2, 3, 5, 7 and 8 shall come into force— (a) for the purpose of proceedings preliminary or relating to any election to be held on 2nd May 2002, on 15th October 2001; (b) for all other purposes, on 2nd May 2002. (3) Article 4 of this Order shall come into force— (a) for the purpose for proceedings preliminary or relating to the election of parish councillors for the parish of Aughton to be held on 1st May 2003, on 15th October 2002; (b) for all other purposes, on 1st May 2003. (4) Article 6 of this Order shall come into force— (a) for the purpose of proceedings preliminary or relating to the election of parish councillors for the parish of Up Holland to be held on 6th May 2004, on 15th October 2003; (b) for all other purposes, on 6th May 2004. -

Notes on North Meols

NOTES ON NORTH MEOLS. By F, H. Cheetham, F.S.A. Read March I3th, 1924. I. DID ST. CUTHBERT'S BODY REST THERE ? fTlHE churches of North Meols and Halsall are both JL dedicated to St. Cuthbert. It has sometimes been supposed that Halsall was one of the resting places of the saint's body during its seven years' wanderings while the Danes were ravaging Northumbria (875-883),1 and the same supposition, sometimes dignified by the name of " tradition," has been advanced as regards North Mcols. Of recent years local historians have made much of this belief and, not satisfied with mere " tradition," have ended by turning it into historical fact.2 Others, less bold, have adopted a half-way course. Thus the late bishop of Sodor and Man, Dr. James Denton Thompson, in 1904, when rector of North Meols, wrote: There can be little doubt that the foundation of the church must be traced to the time of the Danish invasion A.D. 875. During that period, with a view to preserving the body of their patron St. Cuthbert from unholy hands, the monks of Lindisfarne carried the corpse from place to place for about seven years. 1 See V.C.H. Lanes., iii, 188. 2 Notes on Southport and District, 1908, by the Rev. W. T. Bulpit, p. 53; The Spires, Towers, etc., of Southporl, 1922, by Joseph Pearce. In every Anglican church in Southport is exhibited a framed list of the rectors of North Meols, with notes on outstanding events in the ecclesiastical life of the parish. -

NOTICE of ELECTION Election of Parish Councillors

NOTICE OF ELECTION West Lancashire Borough Council Election of Parish Councillors for the Parish Wards listed below Number of Parish Number of Parish Parish Wards Councillors to be Parish Wards Councillors to be elected elected Aughton - Christ Church Three Aughton - Delph Three Aughton - Holt Green One Aughton - North East Two Aughton - Town Green Three Bickerstaffe Eight Dalton Five Hilldale Five Lathom South Seven North Meols - Banks Seven North Meols - Crossens Two Parbold Ten Simonswood Five Tarleton - Central Six Tarleton - Hesketh Lane Four Tarleton - Mere Brow Two Wrightington - Appley Bridge Four Wrightington - Mossy Lea Four 1. Forms of nomination for the Parish Elections may be obtained at 52 Derby Street, Ormskirk, West Lancashire, L39 2DF from the Returning Officer who will, at the request of an elector for any electoral area prepare a nomination paper for signature. 2. Nomination papers must be delivered to the Returning Officer, 52 Derby Street, Ormskirk, West Lancashire, L39 2DF between 9:30am and 4:00pm on any working day after the date of this notice, but no later than 4:00pm on Wednesday, 3 April 2019. 3. If any election is contested the poll will take place on Thursday, 2 May 2019. 4. Applications to register to vote must reach the Electoral Registration Officer, 52 Derby Street, Ormskirk, West Lancashire, L39 2DF by midnight on Friday, 12 April 2019. Applications can be made online: https://www.gov.uk/register-to-vote. 5. Applications, amendments or cancellations of postal votes must reach the Electoral Registration Officer, 52 Derby Street, Ormskirk, West Lancashire, L39 2DF by 5:00pm on Monday, 15 April 2019. -

Infrastructure Delivery Schedule

AMR / IFS: Infrastructure Delivery Schedule ID Status Project name Project description Location Parish Area (if Organisation name Project partners Infrastructure Category Sub Category Project started Project applicable) completed 149 Not started Public Right of Way (8-4-FP16) Surface improvement over approximately 470 PROW between Aughton Lancashire County No No metres of public footpath Delph Lane to Council Town Green Lane, Aughton 146 Not started Improvements to railway station Improvements to railway station faciltiies Aughton Town Aughton Network Rail No No faciltiies Green Station 145 Not started Improvements to railway station Improvements to railway station faciltiies Aughton Park Aughton Network Rail No No faciltiies Station 108 Not started Surface water flooding study Surface water study investigation into flooding Parrs Lane/Prescot Aughton LCC WLBC Green No No investigation Road and Town Green Lane, Aughton 123 Not started Flood prevention works, Bickerstaffe Installation of flood prevention infrastructure Two areas of Bickerstaffe LCC Green Water No No in consultation with LCC flood management Bickerstaffe Ward team flooded in December 2015 a) Coach Road, Barrow Nook b) Royal Oak, in relation to flooded culverts of Knoll Brook 117 Not started Bickerstaffe Gateway to Green Car parking facilities / improvements Bickerstaffe QE2 Bickerstaffe Bickerstaffe Parish WLBC Leisure No No Spaces (including flood risk management) for access field in trust, Hall Council to open green space, park area, sports lane, Bickerstaffe facilities,