E-Governance and Corruption in the States Can Technology Serve the Aam Aadmi?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Growing Cleavages in India? Evidence from the Changing Structure of Electorates, 1962-2014

WID.world WORKING PAPER N° 2019/05 Growing Cleavages in India? Evidence from the Changing Structure of Electorates, 1962-2014 Abhijit Banerjee Amory Gethin Thomas Piketty March 2019 Growing Cleavages in India? Evidence from the Changing Structure of Electorates, 1962-2014 Abhijit Banerjee, Amory Gethin, Thomas Piketty* January 16, 2019 Abstract This paper combines surveys, election results and social spending data to document the long-run evolution of political cleavages in India. From a dominant- party system featuring the Indian National Congress as the main actor of the mediation of political conflicts, Indian politics have gradually come to include a number of smaller regionalist parties and, more recently, the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP). These changes coincide with the rise of religious divisions and the persistence of strong caste-based cleavages, while education, income and occupation play little role (controlling for caste) in determining voters’ choices. We find no evidence that India’s new party system has been associated with changes in social policy. While BJP-led states are generally characterized by a smaller social sector, switching to a party representing upper castes or upper classes has no significant effect on social spending. We interpret this as evidence that voters seem to be less driven by straightforward economic interests than by sectarian interests and cultural priorities. In India, as in many Western democracies, political conflicts have become increasingly focused on identity and religious-ethnic conflicts -

Village Politics in Kerala—I

THE ECONOMIC WEEKLY February 20, 1965 Village Politics in Kerala—I Kathleen Gough The arrest of 800 Leftist Communists at the end of 1964, 150 of them from Kerala, raises such questions as who supports the Leftists, why, and how political parties operate in Kerala*s villages. I shall discuss these questions with reference to a village in central Kerala, using comparative data from a second village in the northern part of the State. My first acquaintance with these villages was in 1948 and 1949. 1 returned to restudy them between April and September 1964, It is not suggested that these villages are typical of Kerala communities. Both, for example, contain a majority of Leftist Communist supporters, and both form wards within Leftist-dominated panchayats. (1 do not know what proportion of Kerala's 922 panchayats are dominated by the Leftists, but probably rather less than a third, judging by estimates received from district party offices). In both villages only one other party, the Congress, has an active organization, In both, the S S P and the Rightist Communists each, in 1964, had only one or two supporters; in the northern village, some half dozen Muslim families supported the Muslim League. Kerala's smaller parties, such as the Revolutionary Socialist Party and the Christian Karshaka Thozhilali Party, are more locally based and in these villages had no supporters at all. Situated in the midland farming areas, the two villages can also afford no insight into politics on the large tea and rubber estates to the east, the coastal fishing or coir or cashew-nut processing communities, or the bigger ports. -

LIST of RECOGNISED NATIONAL PARTIES (As on 11.01.2017)

LIST OF RECOGNISED NATIONAL PARTIES (as on 11.01.2017) Sl. Name of the Name of President/ Address No. Party General secretary 1. Bahujan Samaj Ms. Mayawati, Ms. Mayawati, Party President President Bahujan Samaj Party 4, Gurudwara Rakabganj Road, New Delhi –110001. 2. Bharatiya Janata Shri Amit Anilchandra Shri Amit Anilchandra Shah, Party Shah, President President Bharatiya Janata Party 11, Ashoka Road, New Delhi – 110001 3. Communist Party Shri S. Sudhakar Reddy, Shri S. Sudhakar Reddy, of India General Secretary General Secretary, Communist Party of India Ajoy Bhawan, Kotla Marg, New Delhi – 110002. 4. Communist Party Shri Sitaram Yechury, Shri Sitaram Yechury, of General Secretary General Secretary India (Marxist) Communist Party of India (Marxist) ,A.K.Gopalan Bhawan,27-29, Bhai Vir Singh Marg (Gole Market), New Delhi - 110001 5. Indian National Smt. Sonia Gandhi, Smt. Sonia Gandhi, Congress President President Indian National Congress 24,Akbar Road, New Delhi – 110011 6. Nationalist Shri Sharad Pawar, Shri Sharad Pawar, Congress Party President President Nationalist Congress Party 10, Bishambhar Das Marg, New Delhi-110001. 7. All India Ms. Mamta Banerjee, All India Trinamool Congress, Trinamool Chairperson 30-B, Harish Chatterjee Street, Congress Kolkata-700026 (West Bengal). LIST OF STATE PARTIES (as on 11.01.2017) S. No. Name of the Name of President/ Address party General Secretary 1. All India Anna The General Secretary- No. 41, Kothanda Raman Dravida Munnetra in-charge Street, Chennai-600021, Kazhagam (Tamil Nadu). (Puratchi Thalaivi Amma), 2. All India Anna The General Secretary- No.5, Fourth Street, Dravida Munnetra in-charge Venkatesware Nagar, Kazhagam (Amma), Karpagam Gardens, Adayar, Chennai-600020, (Tamil Nadu). -

{Olitical Thereby He Has Become Subject to Disqualification on the Ground of Defection Under the Tenth Schedule and Petitioner Prayed for a Declaration

: (['ite No.40l0flable-ll20lStLog.'1 Legislative Assembly from No.70, Irinjalakuda Constituency filed this petition under Rule 6(2) of the Members of Kerala Legislative Assembly (Disqualification on ground of Defectipn) Rules 19g6 (for short hereinafter referred to as Rules) for disqtralification of Shri p.C George who was elected from constituency No.l0l Poonjar with following alegations; Kerala Congress 2) (M) is a recognised political par,ty with "Randilla,, (.,two leaves,,) syrnbol and respondent ,as Shri. PC. George contested assembly election and elected from No.l0l Poonjar assembly constituency as a candidate set up by Kerala Congress (M) and was functioning as Government Chief Whip Sttri. K.M. Mani is the party chairman and Legislature p.rry leader. Legislature pmty leader submitted Form I showing respondent as a member in **ro*.. ;; Rule (2g) and Fonrr III under Rule 4(2).Respondents name is shown as the member of Kerala Congress (M) in Form IV and the register kept by Legislature secletary under Rule 5(l).Kerala Clnsress (lv0 a constitoerrt fs ofUDF coalition. Respondent has vohurtarily given up his membership of Kerala Congress (M).He acted against his political party and UDF *i i*rrd statem*t, uguinrt the party and UDF. On 03.0 6.7A15 he send a letter to Speaker seeking permissi"" ;;;;;;;; UDF He revived his political party named Kerala Congress (Secular) and set up his own candidbte and campaigned for him inAnrvikara by-election conducted on2l.A6.2015 *d irr,rrd statements in news papers against UDF cantlidate and in favour ofACDF candidate set up by him. -

Is the Coalition Era Over in Indian Politics? Adnan Farooquia & E

This article was downloaded by: [Columbia University] On: 06 December 2014, At: 19:49 Publisher: Routledge Informa Ltd Registered in England and Wales Registered Number: 1072954 Registered office: Mortimer House, 37-41 Mortimer Street, London W1T 3JH, UK The Round Table: The Commonwealth Journal of International Affairs Publication details, including instructions for authors and subscription information: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/ctrt20 Is the Coalition Era Over in Indian Politics? Adnan Farooquia & E. Sridharanb a Department of Political Science, Jamia Millia Islamia, New Delhi, India b University of Pennsylvania Institute for the Advanced Study of India, New Delhi, India Published online: 04 Dec 2014. Click for updates To cite this article: Adnan Farooqui & E. Sridharan (2014): Is the Coalition Era Over in Indian Politics?, The Round Table: The Commonwealth Journal of International Affairs To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/00358533.2014.988457 PLEASE SCROLL DOWN FOR ARTICLE Taylor & Francis makes every effort to ensure the accuracy of all the information (the “Content”) contained in the publications on our platform. However, Taylor & Francis, our agents, and our licensors make no representations or warranties whatsoever as to the accuracy, completeness, or suitability for any purpose of the Content. Any opinions and views expressed in this publication are the opinions and views of the authors, and are not the views of or endorsed by Taylor & Francis. The accuracy of the Content should not be relied upon and should be independently verified with primary sources of information. Taylor and Francis shall not be liable for any losses, actions, claims, proceedings, demands, costs, expenses, damages, and other liabilities whatsoever or howsoever caused arising directly or indirectly in connection with, in relation to or arising out of the use of the Content. -

THE INDIAN NATIONAL CONGRESS PARTY AFTER the DYNASTY by CSABA NIKOLENYI B.A., Memorial University of Newfoundland, 1993

THE INDIAN NATIONAL CONGRESS PARTY AFTER THE DYNASTY by CSABA NIKOLENYI B.A., Memorial University of Newfoundland, 1993 A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS in THE FACULTY OF GRADUATE STUDIES (Department of Political Science) We accept this thesis as conforming "to the requj,xg^ standard THE UNIVERSITY OF BRITISH COLUMBIA September 1994 (c) Csaba Nikolenyi, 1994 In presenting this thesis in partial fulfillment of the requirements for an advanced degree at the University of British Columbia, I agree that the Library shall make it freely available for reference and study. I further agree that permission for extensive copying of this thesis for scholarly purposes may be granted by the head of my department or by his or her representatives. It is understood that copying or publication of this thesis for financial gain shall not be allowed without my written permission. (Signature) Department of ?o(Vfl"c^l ^C.i<i-^C^ The University of British Columbia Vancouver, Canada Date S^^t^kf !^,l^^h 11 ABSTRACT Rajiv Gandhi's violent death in May 1991 signalled the end of an entire era for the Congress Party: the long-lasting rule of the dynasty was over. Subsequent developments in the party have raised the question of change versus continuity. Has the end of the dynasty led to the birth of a new Congress, or will the dynastic party structures and organizational features continue into the post-Gandhi period? The argument that I will be advancing throughout the thesis is that structural continuity has characterized the organizational order of the party in its post- dynastic period. -

The Kerala Election: a Shift to the Left – and a Move to the Right

The Kerala election: A shift to the left – and a move to the right blogs.lse.ac.uk/southasia/2016/05/26/the-kerala-election-a-shift-to-the-left-and-a-move-to-the-right/ 2016-5-26 Last week Kerala’s electoral pendulum swung to once again favour the Left Democratic Front over the Congress-led United Democratic Front. But James Chiriyankandath writes that this year’s contest was unusual in that the BJP emerged as a more credible third force, suggesting the cycle that has developed in the last 60 years is no longer as stable as it looks. This article forms part of a series on the 2016 Legislative Assembly Elections. Click here to read more. In the six decades since the coastal south Indian state was formed and made history by becoming the first anywhere in the world to return a communist government to power through the ballot box in 1957, elections in Kerala have been remarkably consistent. Coalitions led by either the communists or the Congress Party – since 1982 the Left Democratic Front (LDF) or the United Democratic Front (UDF) – have alternated in winning all but one of thirteen elections (the exception was in 1977). The results of the polls on 16 May were no different: the LDF succeeded in ousting the UDF from office, claiming 91 of the 140 state assembly seats to 47 for the UDF. Yet this was an unusual electoral contest with the Hindu nationalist Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) of Prime Minister Narendra Modi, perennial ‘also-rans’ in Kerala but in power at the centre since 2014, gaining a seat for the first time; the remaining seat went to an independent. -

The Walkout in India: No Longer 'Left' in the Lurch

ISAS Brief No. 73 – Date: 9 July 2008 469A Bukit Timah Road #07-01,Tower Block, Singapore 259770 Tel: 6516 6179 / 6516 4239 Fax: 6776 7505 / 6314 5447 Email: [email protected] Website: www.isas.nus.edu.sg The Walkout in India: No Longer ‘Left’ in the Lurch ∗ Bibek Debroy With the Left [the Communist Party of India-Marxist (CPI-M), the Communist Party of India, the Forward Bloc and Revolutionary Socialist Party] planning to meet President Pratibha Devisingh Patil on 9 July 2008 and submit a letter withdrawing support from the United Progressive Alliance (UPA) government, the overall numbers game seems simple. There are two vacancies and the Lok Sabha now has 543 members. A simple majority requires 272 members. The UPA (the Congress Party, Rashtriya Janata Dal, Dravida Munnettra Kazhagam, the Nationalist Congress Party, Pattali Makkal Katchi, Jharkhand Mukti Morcha, Lok Janshakti Party, Kerala Congress, the Muslim League, Republican Party of India, All India Majlis-e-Ittehadul Muslimeen, Peoples Democratic Party, Sikkim Democratic Front and three Independents) has 231 seats (the Congress Party has 153 seats). With the Left’s 59 Members of Parliament having quit, the UPA has lost its majority. However, to all intents and purposes, the Samajwadi Party (SP) has provided support to the UPA through its 39 members, leaving UPA with only two members short of a majority. But it isn’t that simple. There is dissidence within the SP too, and at least seven (if not 10) of its Members of Parliament may not end up supporting the government. Indeed, there are question marks about support from some of the UPA constituents too. -

6269 South Asia 070104.Indd

Political Parties in South Asia: Th e Challenge of Change South Asia Regional Report Based on research and dialogue with political parties Political Parties in South Asia: Th e Challenge of Change South Asia Regional Report Based on research and dialogue with political parties Lead Author: K. C. Suri Nagarjuna University India International IDEA Research and Dialogue Coordination: Roger Hällhag Head of the Political Parties Programme Sakuntala Kadirgamar-Rajasingham Head of the South Asia Programme Maja Tjernström Programme Offi cer, Political Parties Programme James Gomez Programme Offi cer, Political Parties Programme About this report Political parties are indispensable for making democracy work and deliver. Finding the proper conditions for the better internal functioning and effective legal regulation of political parties is of key importance anywhere. This report is the result of worldwide research and dialogue with political parties. Together with national and regional research partners, International IDEA is improving insight and comparative knowledge. The purpose is to provide for constructive public debate and reform actions helping political parties to develop. For more about the Political Parties programme, please visit http://www.idea.int/parties. Political Parties in South Asia: The Challenge of Change © International Institute for Democracy and Electoral Assistance 2007 This is an International IDEA publication. International IDEA publications are independent of specifi c national or political interests. Views expressed in this publication do not necessarily represent the views of International IDEA, its Board or its Council members. Applications for permission to reproduce or translate all or any part of this publication should be made to: Publications Offi ce International IDEA SE 103 34 Stockholm Sweden International IDEA encourages dissemination of its work and will promptly respond to requests for permission to reproduce or translate its publications. -

Party Position in 16Th Lok Sabha

Party Position in 16th Lok Sabha SS, 18 BJD, 20 BJP, 281 TMC, 34 AIADMK, 37 INC, 44 Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) (281) Indian National Congress INC(44) All India Anna Dravida Munnetra Kazhagam (AIADMK) (37) All India Trinamool Congress (TMC)(34) Biju Janata Dal (BJD) (20) Shivsena (SS)(18) Telugu Desam (TDP)(16) Telangana Rashtra Samithi (TRS)(11) Communist Party of India (Marxist) CPI(M) (9) Yuvajana Sramika Rythu Congress Party (YSRCP)(9) Nationalist Congress Party (6) Lok Jan Shakti Party (6) Samajwadi Party (5) Aam Aadmi Party (4) Rashtriya Janata Dal (4) Shiromani Akali Dal (4) All India United Democratic Front (3) Jammu & Kashmir Peoples Democratic Party (3) Rashtriya Lok Samta Party (3) Independents (3) Indian National Lok Dal (2) Indian Union Muslim League (2) Janata Dal (Secular) (2) Janata Dal (United) (2) Jharkhand Mukti Morcha (2) Apna Dal (2) Communist Party of India (1) All India N.R. Congress (1) Kerala Congress (M) (1) Naga Peoples Front (1) National Peoples Party (1) Pattali Makkal Katchi (1) Revolutionary Socialist Party (1) Sikkim Democratic Front (1) All India Majlis-E-Ittehadul Muslimeen (1) Swabhimani Paksha (1) AS ON 19.02.2015 Women Members in 16th Lok Sabha Female (66) 12% Male (476) Female (66) Male (476) 88% Party-wise list of Women Members in 16th Lok Sabha 1 Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP,32) 2 All India Trinamool Congress (AITMC,13) 3 Indian National Congress (INC,4) 4 All India Anna Dravida Munnetra Kazhagam (AIADMK,4) 5 Biju Janata Dal (BJD,3) 6 Yuvajana Sramika Rythu Congress Party (YSRCP,2) 7 Jammu and Kashmir Peoples Democratic Party (1) 8 Communist Party of India (Marxist) (1) 9 Telangana Rashtra Samithi (1) 10 Shiv Sena (1) 11 Nationalist Congress Party (1) 12 Lok Jan Shakti Party (1) 13 Samajwadi Party (1) 14 Shiromani Akali Dal (1) 15 Apna Dal (1) . -

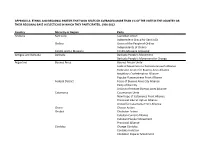

Appendix A: Ethnic and Regional Parties That Won

APPENDIX A: ETHNIC AND REGIONAL PARTIES THAT WON SEATS OR AVERAGED MORE THAN 1% OF THE VOTE IN THE COUNTRY OR THEIR REGIONAL BASE IN ELECTIONS IN WHICH THEY PARTICIPATED, 1990-2012 Country Minority or Region Party Andorra Sant Julià Lauredian Union Independent Group for Sant Julià Ordino Union of the People of Ordino Independents of Ordino Canillo and La Massana Canillo-Massana Grouping Antigua and Barbuda Barbuda Barbuda People's Movement Barbuda People's Movement for Change Argentina Buenos Aires Buenos Airean Unity Federal Movement to Recreate Growth Alliance Federalist Action for Buenos Aires Alliance Neighbors Confederation Alliance Popular Bueonsairean Front Alliance Federal District Force of Buenos Aires City Alliance Party of the City Union to Recreate Buenos Aires Alliance Catamarca Catamarcan Unity New Hope of Catamarca Front Alliance Provincial Liberal Option Alliance United for Catamarca Front Alliance Chaco Chacan Action Chubut Chubutan Action Cubutan Current Alliance Cubutan Popular Movement Provincial Alliance Córdoba Change Córdoba Córdoba in Action Córdoban Popular Movement Country Minority or Region Party The People First – Neighborly Union of Córdoba Alliance Together for Córdoba Alliance Union for Córdoba Alliance Corrientes Autonomous Liberal Pact-Popular Democratic Autonomous Liberal Pact-Progressive Democrat- Christian Democrat Civic and Social Front of Corrientes Corrientan Action Corrientan Front Corrientes Project Front Alliance Liberal-Autonomist Pact-Progressive Democratic-Union of the Democratic Center Alliance -

The Religious Clashes in India and Their Impact On

MASARYKOVAUNIVERZITA FAKULTA SOCIÁLNÍCH STUDIÍ Katedra politologie THE RELIGIOUS CLASHES IN INDIA AND THEIR IMPACT ON ELECTION RESULTS BAKALÁŘSKÁ PRÁCE Ladislav Kudláček Vedoucí práce: Mgr. Tomáš Šmíd UČO: 42062 Obor: PL – EVS Imatrikulační ročník: 2003 Brno, 2006 Prohlašuji,že jsem tutobakalářskou práci na oboru politologie Fakultysociálních studií Masarykovyuniverzityvypracoval samostatně apouze zapoužití uvedených pramenů a literatury. .................................................. LadislavKudláček student bakalářskéhokombinovanéhodvouoborovéhostudia politologie-evropskástudia 1 Poděkování Srdečně děkuji vedoucímu práce Mgr. Tomáši Šmídovi za odborné vedení práce a Delii Červínkové za pomoc při jazykovékorektuře. LadislavKudláček 2 “I have nothing new to teach the world. Truth and non-violence are as old as the hills.” Mohandas KaramchandGandhi 3 Contents: Introduction ................................................................................................................................ 6 1. ThecleavagesinIndianpolitics–shortdescription ...................................................... 7 1.1. Chaturvarna–Indiancastesystem ......................................................................... 7 1.2. ModernIndianclass society ................................................................................... 8 1.3. Cleavages betweenurbanandruralareas .............................................................. 9 2. ThemainreligioninIndia ...........................................................................................