Chinese Seafood: Safety and Trade Issues Hearing One

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Sagawkit Acceptancespeechtran

Screen Actors Guild Awards Acceptance Speech Transcripts TABLE OF CONTENTS INAUGURAL SCREEN ACTORS GUILD AWARDS ...........................................................................................2 2ND ANNUAL SCREEN ACTORS GUILD AWARDS .........................................................................................6 3RD ANNUAL SCREEN ACTORS GUILD AWARDS ...................................................................................... 11 4TH ANNUAL SCREEN ACTORS GUILD AWARDS ....................................................................................... 15 5TH ANNUAL SCREEN ACTORS GUILD AWARDS ....................................................................................... 20 6TH ANNUAL SCREEN ACTORS GUILD AWARDS ....................................................................................... 24 7TH ANNUAL SCREEN ACTORS GUILD AWARDS ....................................................................................... 28 8TH ANNUAL SCREEN ACTORS GUILD AWARDS ....................................................................................... 32 9TH ANNUAL SCREEN ACTORS GUILD AWARDS ....................................................................................... 36 10TH ANNUAL SCREEN ACTORS GUILD AWARDS ..................................................................................... 42 11TH ANNUAL SCREEN ACTORS GUILD AWARDS ..................................................................................... 48 12TH ANNUAL SCREEN ACTORS GUILD AWARDS .................................................................................... -

Newsletter 03/12 DIGITAL EDITION Nr

ISSN 1610-2606 ISSN 1610-2606 newsletter 03/12 DIGITAL EDITION Nr. 307 - Februar 2012 Michael J. Fox Christopher Lloyd LASER HOTLINE - Inh. Dipl.-Ing. (FH) Wolfram Hannemann, MBKS - Talstr. 11 - 70825 K o r n t a l Fon: 0711-832188 - Fax: 0711-8380518 - E-Mail: [email protected] - Web: www.laserhotline.de Newsletter 03/12 (Nr. 307) Februar 2012 editorial Hallo Laserdisc- und DVD-Fans, gerüchteweise bereits Angelina Jolies liebe Filmfreunde! Regiedebüt IN THE LAND OF BLOOD Wer die Disney-Filme und ganz beson- AND HONEY, das die hübsche Dame ders deren Prinzessinnen mag, der soll- gerade auf der Berlinale vorgestellt hat, te sich die Kolumne unserer Schreibe- auf silbernen und blauen Scheiben ge- rin Anna ab Seite 3 aufmerksam durch- ben. lesen. Ihr tiefgründiges Hinterfragen der Frauenfiguren in Disneys weich- Trotz der riesigen Schwemme von Neu- gespülten Animationsklassikern ist erscheinungen haben wir natürlich un- durchaus berechtigt. Für Risiken und seren eigenen Film nicht vergessen. Nebenwirkungen, die der Aufsatz bei THE GIRL WITH THE THORN TAT- Ihrem nächsten Konsum von DIE TOO (Ähnlichkeiten mit anderen Fil- SCHÖNE UND DAS BIEST und Kon- men ist natürlich rein zufällig...) befin- sorten hinterlässt, übernehmen wir na- det sich in der heissen Endphase der türlich keine Haftung! Postproduktion. Inzwischen haben wir die ersten Ergebnisse nicht nur in un- Und damit erst einmal ganz herzlich serem Heimkino evaluiert, sondern willkommen zur neuen Ausgabe unse- auch auf der großen Leinwand in ver- res Newsletters. Sozusagen in letzter schiedenen Kinos getestet. Schließlich Minute erreichten uns noch zwei aktu- soll unser Film nicht nur im kleinen elle Ankündigungen für Deutschland. -

By Tennessee Williams Directed by Cameron Watson Ensemble

Antaeus Theatre Company Presents by Tennessee Williams Directed by Cameron Watson Scenic Designer Costume Designer Steven C. Kemp Terri A. Lewis Lighting Designer Sound Designer Jared A. Sayeg Jeff Gardner Props Designer Production Stage Manager Erin Walley Kristin Weber* Cat on a Hot Tin Roof is presented by special arrangement with Dramatists Play Service, Inc., New York. Ensemble Daniel Bess*, John DeMita*, Dawn Didawick*, Mitchell Edmonds*, Julia Fletcher*, Henry Greenspan, Harry Groener*, Tim Halligan*, Michael Kirby*, Tamara Krinsky*, Eliza LeMoine, Mike McShane*, Rebecca Mozo*, Linda Park*, Ross Philips, Robert Pine*, Vivienne Belle Sievers, Jocelyn Towne*, Helen Rose Warshofsky, Patrick Wenk-Wolff* *Member, Actors’ Equity Association, the union of professional Actors and Stage Managers in the United States. This production is presented under the auspices of the Actors’ Equity Los Angeles Membership Company Rule. The video and/or audio recording of this performance by any means whatsoever are strictly prohibited. Artistic Directors’ Note On behalf of everyone at Antaeus Theatre Company, we’re thrilled to welcome you to the first season in our brand new home, the Kiki & David Gindler Performing Arts Center. It’s been a long journey. In 1991 actor Dakin Matthews and director Lillian Garrett-Groag founded Antaeus with an ensemble of some of LA’s best classically trained actors, meeting in the rehearsal room of the Taper Annex. In 2010, we produced our first full season in our rather cramped lodgings in North Hollywood and quickly -

ALEX KURTZMAN /Executive Producer

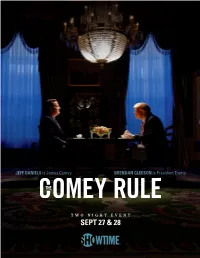

JEFF DANIELS is James Comey BRENDAN GLEESON is President Trump TWO NIGHT EVENT SEPT 27 & 28 SERIES OVERVIEW THE COMEY RULE, starring Emmy® winner Jeff Daniels when Donald Trump stunned the world and was elected (The Newsroom) as former FBI Director James Comey president. Part two is a virtual day-by-day account of the and Emmy winner Brendan Gleeson (Mr. Mercedes) as tempestuous relationship between Comey and Trump and President Donald J. Trump, will premiere on consecutive the intense and chaotic first months of the Trump presidency nights: Sunday, September 27 and Monday, September – where allies became enemies, enemies became friends 28 at 9 PM ET/PT on SHOWTIME®. The two-part event and truth depended on what side you were on. series was adapted for the screen and directed by Oscar® nominated screenwriter Billy Ray (Captain Phillips, Shattered In addition to Daniels and Gleeson, THE COMEY RULE Glass) and executive produced by Shane Salerno, Alex features an ensemble of Oscar, Emmy, Golden Globe® and Kurtzman, Heather Kadin and Billy Ray. Based on Comey’s #1 Tony ® winning talent, including Holly Hunter (The Piano) as New York Times bestselling book A Higher Loyalty and former Acting Attorney General Sally Yates, Michael Kelly more than a year of additional interviews with a number (Tom Clancy's Jack Ryan) as former FBI Director Andrew of key principals, THE COMEY RULE is an immersive, McCabe, Jennifer Ehle (Zero Dark Thirty) as Patrice Comey, behind-the-headlines account of the historically turbulent Scoot McNairy (Halt and Catch Fire) as former Deputy events surrounding the 2016 presidential election and its Attorney General Rod Rosenstein, Jonathan Banks (Better aftermath, which divided a nation. -

Screen Actors Guild Awards Acceptance Speech Transcripts TABLE of CONTENTS INAUGURAL SCREEN ACTORS GUILD AWARDS

Screen Actors Guild Awards Acceptance Speech Transcripts TABLE OF CONTENTS INAUGURAL SCREEN ACTORS GUILD AWARDS ...........................................................................................2 2ND ANNUAL SCREEN ACTORS GUILD AWARDS .........................................................................................6 3RD ANNUAL SCREEN ACTORS GUILD AWARDS ...................................................................................... 11 4TH ANNUAL SCREEN ACTORS GUILD AWARDS ....................................................................................... 15 5TH ANNUAL SCREEN ACTORS GUILD AWARDS ....................................................................................... 20 6TH ANNUAL SCREEN ACTORS GUILD AWARDS ....................................................................................... 24 7TH ANNUAL SCREEN ACTORS GUILD AWARDS ....................................................................................... 28 8TH ANNUAL SCREEN ACTORS GUILD AWARDS ....................................................................................... 32 9TH ANNUAL SCREEN ACTORS GUILD AWARDS ....................................................................................... 36 10TH ANNUAL SCREEN ACTORS GUILD AWARDS ..................................................................................... 42 11TH ANNUAL SCREEN ACTORS GUILD AWARDS ..................................................................................... 48 12TH ANNUAL SCREEN ACTORS GUILD AWARDS .................................................................................... -

Read the Program

Antaeus Theatre Company Presents by William Shakespeare Directed by Rob Clare Scenic Designer Costume Designer François-Pierre Couture A. Jeffrey Schoenberg Lighting Designer Composer & Sound Designer Leigh Allen Peter Bayne Props Designer Production Stage Manager Anya Allyn Kolesnikoff Kristin Weber* Ensemble Brian Abraham*, Bernard K. Addison*, Tony Amendola*, Ben Atkinson, John Bobek*, Wayne T. Carr*, JD Cullum*, Paul Culos, Julia Davis*, John DeMita*, Daniel Dorr, Mitchell Edmonds*, Matthew Gallenstein, Eve Gordon*, Tim Halligan*, Steve Hofvendahl*, Sally Hughes*, Desirée Mee Jung*, Luis Kelly-Duarte, Anna Lamadrid, Ian Littleworth*, Abigail Marks*, Adam Meyer*, Elyse Mirto*, Erin Pineda*, Adam J. Smith*, Janellen Steininger*, James Sutorius*, Sedale Threatt, Jr., Daisuke Tsuji*, Todd Waring*, Karen Malina White* *Member, Actors’ Equity Association, the union of professional Actors and Stage Managers in the United States. This production is presented under the auspices of the Actors’ Equity Los Angeles Membership Company Rule. The video and/or audio recording of this performance by any means whatsoever are strictly prohibited. Artistic Directors’ Note On behalf of everyone at Antaeus Theatre Company, we’re thrilled to welcome you to the first season in our brand new home, the Kiki & David Gindler Performing Arts Center. It’s been a long journey. In 1991, actor Dakin Matthews and director Lillian Garrett-Groag founded Antaeus with an ensemble of some of LA’s best classically trained actors, meeting in the rehearsal room of the Taper Annex. -

Several Arrested on Drug Charges

Herald-CitizenHerald-CitizenNEW CHS HOOPS COACH Josh Heard. D1 SUNDAY, JUNE 16, 2019 | COOKEVILLE, TENNESSEE 117TH YEAR | NO. 129 $1.50 Judge issues restraining order in Bee Rock suit BY JIM HERRIN Court Judge Jonathan Young. no other parties would be al- on two occasions, the town of visit Bee Rock. That’s just the HERALD-CITIZEN “I’m going to issue a tem- lowed vehicular access until Monterey has now sued The truth of the matter,” he said. porary restraining order that the suit is settled. Garden Inn seeking to have Attorney Michael Kress, The town of Monterey will the town of Monterey ... can The town received about the matter settled. representing The Garden be allowed to drive vehicles take their equipment across 10 acres of the Bee Rock Attorney Danny Rader Inn, countered that allow- across a disputed easement the easement (and) fi x up property as a gift last year, argued in court Friday that ing vehicular traffi c would to the Bee Rock natural area their property,” Young said. but the owners of The Gar- “the law is crystal clear” that change the “status quo” of the as they prepare for a park He also ruled that Monte- den Inn, which sits adjacent the easement included when easement and cause harm to dedication ceremony later rey would be allowed to use to Bee Rock, had fi led suit the property was sold does his clients. this month. a golf cart or similar vehicle challenging the scope of the allow “all types of traffi c.” “There’s not been any ve- That ruling came in a to transport people to the easement. -

Voices of California | Objects of Her Desire | Paradise Found | an Improbable Journey

VOICES OF CALIFORNIA | OBJECTS OF HER DESIRE | PARADISE FOUND | AN IMPROBABLE JOURNEY SUMMER 2019 T H E C A L I F O R N I A I S S U E THE MAGAZINE OF WAKE FOREST UNIVERSITY FEATURES 6 VOICES OF CALIFORNIA By Carol L. Hanner, Maria Henson (’82) and Kerry M. King (’85) What’s it like these days to be a Demon Deacon on the other coast? Wake Foresters tell us about their lives in The Golden State. ROBBY McCULLOUGH 2 60 AN IMPROBABLE JOURNEY THE OBJECTS OF HER DESIRE By John Meroney (’94) By Carol L. Hanner A native North Carolinian comes to understand For Susan Harlan, native Californian, author the spell cast by California — and its magic. and associate professor of English, every kitschy, cherished, poignant item in her eclectic collection has a story. 42 104 PARADISE FOUND CONSTANT & TRUE By Kerry M. King (’85) By Pidge Meade (’89) Woody Faircloth (’90) didn’t feel right about Here to say that moving and shaking leads to sending only thoughts and prayers to victims growth (and “Jeopardy!” championships). of the Camp Fire in California. Instead, he started with one RV, and a host of his “angels” have helped continue the giving. 58 DEPARTMENTS STARTUP 70 Commencement 77 Philanthropy By Maria Henson (’82) 72 Distinguished Alumni Awards 78 Class Notes Wake Forest has planted its flag in the San Francisco Bay Area with the Silicon Valley 74 Around the Quad Practicum. WAKEFOREST FROM theh PRESIDENT MAGAZINE the summer issue celebrates california, with its growing SUMMER 2019 | VOLUME 66 | NUMBER 3 alumni base and new opportunities for our students.