Preliminary Thesis Outline

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

List of CMU Members 2021-08-18

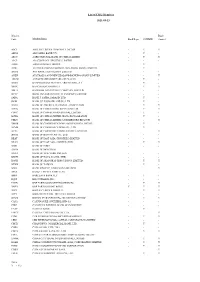

List of CMU Members 2021-09-23 Member Bond Code Member Name Bank Repo CMUBID Connect ABCI ABCI SECURITIES COMPANY LIMITED - Y Y ABNA ABN AMRO BANK N.V. - Y - ABOC AGRICULTURAL BANK OF CHINA LIMITED - Y Y AIAT AIA COMPANY (TRUSTEE) LIMITED - - - ASBK AIRSTAR BANK LIMITED - Y - ACRL ALLIED BANKING CORPORATION (HONG KONG) LIMITED - Y - ANTB ANT BANK (HONG KONG) LIMITED - - - ANZH AUSTRALIA AND NEW ZEALAND BANKING GROUP LIMITED - - Y AMCM AUTORIDADE MONETARIA DE MACAU - Y - BEXH BANCO BILBAO VIZCAYA ARGENTARIA, S.A. - Y - BSHK BANCO SANTANDER S.A. - Y Y BBLH BANGKOK BANK PUBLIC COMPANY LIMITED - - - BCTC BANK CONSORTIUM TRUST COMPANY LIMITED - - - SARA BANK J. SAFRA SARASIN LTD - Y - JBHK BANK JULIUS BAER AND CO. LTD. - Y - BAHK BANK OF AMERICA, NATIONAL ASSOCIATION - Y Y BCHK BANK OF CHINA (HONG KONG) LIMITED - Y Y CDFC BANK OF CHINA INTERNATIONAL LIMITED - Y - BCHB BANK OF CHINA LIMITED, HONG KONG BRANCH - Y - CHLU BANK OF CHINA LIMITED, LUXEMBOURG BRANCH - - Y BMHK BANK OF COMMUNICATIONS (HONG KONG) LIMITED - Y - BCMK BANK OF COMMUNICATIONS CO., LTD. - Y - BCTL BANK OF COMMUNICATIONS TRUSTEE LIMITED - - Y DGCB BANK OF DONGGUAN CO., LTD. - - - BEAT BANK OF EAST ASIA (TRUSTEES) LIMITED - - - BEAH BANK OF EAST ASIA, LIMITED (THE) - Y Y BOIH BANK OF INDIA - - - BOFM BANK OF MONTREAL - - - BNYH BANK OF NEW YORK MELLON - - - BNSH BANK OF NOVA SCOTIA (THE) - - - BOSH BANK OF SHANGHAI (HONG KONG) LIMITED - Y Y BTWH BANK OF TAIWAN - Y - SINO BANK SINOPAC, HONG KONG BRANCH - - Y BPSA BANQUE PICTET AND CIE SA - - - BBID BARCLAYS BANK PLC - Y - EQUI BDO UNIBANK, INC. -

Bank of Jiujiang Co., Ltd.* * (A Joint Stock Company Incorporated in the People’S Republic of China with Limited Liability) (Stock Code: 6190)

Hong Kong Exchanges and Clearing Limited and The Stock Exchange of Hong Kong Limited take no responsibility for the contents of this announcement, make no representation as to its accuracy or completeness and expressly disclaim any liability whatsoever for any loss howsoever arising from or in reliance upon the whole or any part of the contents of this announcement. Bank of Jiujiang Co., Ltd.* * (A joint stock company incorporated in the People’s Republic of China with limited liability) (Stock Code: 6190) ANNOUNCEMENT PROPOSED RE-ELECTION AND APPOINTMENT OF DIRECTORS AND SUPERVISORS PROPOSED AMENDMENTS TO THE ARTICLES OF ASSOCIATION ESTABLISHMENT OF COMPLIANCE MANAGEMENT COMMITTEE OF THE BOARD I. PROPOSED RE-ELECTION AND APPOINTMENT OF DIRECTORS According to the relevant laws and regulations and the Articles of Association of Bank of Jiujiang Co., Ltd. (the “Articles of Association”), the directors (“Directors”) of Bank of Jiujiang Co., Ltd.* (the “Bank”) shall serve a term of three years. The term of a Director is renewable by re-election after its expiry, but the cumulative term of office for independent non- executive Directors at the Bank shall not exceed six years. The term of the fifth session of the Board of the Bank will soon expire, and a re-election is proposed. The board of Directors (the “Board”) of the Bank has resolved at the Board meeting held on 30 March 2020 to propose the nomination of Mr. LIU Xianting, Mr. PAN Ming and Ms. CAI Liping for re-election as executive Directors of the Bank; the nomination of Mr. ZENG Huasheng, Mr. ZHANG Jianyong, and Mr. -

Primary Dealers (With Effect from 1 October 2021)

HONG KONG SPECIAL ADMINISTRATIVE REGION OF THE PEOPLE’S REPUBLIC OF CHINA GOVERNMENT BOND PROGRAMME List of Primary Dealers (with effect from 1 October 2021) 1. Bank of China (Hong Kong) Limited 2. Bank of Communications Company, Limited 3. BNP Paribas, Hong Kong 4. Citibank N.A. 5. Crédit Agricole Corporate and Investment Bank 6. DBS Bank (Hong Kong) Limited 7. Hang Seng Bank Limited 8. Hongkong and Shanghai Banking Corporation Limited, The 9. Societe Generale 10. Standard Chartered Bank (Hong Kong) Limited List of Recognized Dealers (with effect from 30 September 2021) 1. ABN AMRO Bank N.V. 2. Agricultural Bank of China Limited 3. Airstar Bank Limited 4. Allied Banking Corporation (Hong Kong) Limited 5. Ant Bank (Hong Kong) Limited 6. Australia and New Zealand Banking Group Limited 7. Banco Bilbao Vizcaya Argentaria, S.A. 8. Banco Santander, S.A. 9. Bangkok Bank Public Company Limited 10. Bank Julius Baer & Co. Ltd. 11. Bank of America, National Association 12. Bank of China (Hong Kong) Limited 13. Bank of China International Limited 14. Bank of Communications Company, Limited 15. Bank of Communications (Hong Kong) Limited 16. Bank of Dongguan Co., Ltd. 17. Bank of East Asia, Limited (The) 18. Bank of India 19. Bank of Montreal 20. Bank of Nova Scotia (The) 21. Bank of Taiwan 22. Bank SinoPac, Hong Kong Branch 23. Banque Pictet & Cie SA 24. Barclays Bank plc 25. BDO Unibank, Inc. 26. BNP Paribas, Hong Kong 27. BNP Paribas Securities Services 28. Cathay Bank 29. Cathay United Bank Company, Limited 30. Chang Hwa Commercial Bank, Limited 31. -

2019 Annual Report 2019Re P O Rt Annu a L

l l t A R Annu Repo 2019 HUA XIA BANK CO., LIMITED 2019 ANNUAL REPOrt This report is printed on environmentally friendly paper is printed on environmentally This report Address: Hua Xia Bank Mansion, 22 Jianguomennei Street, Dongcheng District, Beijing Postal code: 100005 District, Beijing Postal Address: Hua Xia Bank Mansion, 22 Jianguomennei Street, Dongcheng 010-85239605 Fax: 010-85239938 010-85238570 Tel: www.hxb.com.cn Website: 2019 Annual Report CONTENTS 3 Message from Chairman 7 Message from President 8 Important Notice 9 Section I Definitions 10 Section II Company Profile 22 Section III Financial Highlights 27 Section IV Discussion and Analysis of Operations 74 Section V Significant Events 84 Section VI Details of Changes in Ordinary Shares and Shareholders 90 Section VII Preference Shares 94 Section VIII Directors, Supervisors, Senior Management Members, Other Employees and Branches 106 Section IX Corporate Governance 112 Section X Financial Statements 113 Section XI List of Documents for Inspection 114 Written Confirmation of the Annual Report 2019 by Directors, Supervisors and Senior Management Members of Hua Xia Bank Co., Limited 117 Auditor’s Report Chairman: Li Minji 2 2019 Annual Report MESSAGE FROM CHAIRMAN The year 2019 marked the 70th anniversary of the several consecutive years. We set up a steering institution founding of the People’s Republic of China, and saw the dedicated to poverty alleviation, put into practice the success of Hua Xia Bank’s fourth Party congress and requirements for precision poverty alleviation work relating defining of the development course. Guided by Xi Jinping to finance, strengthened financial services for poverty Thought on Socialism with Chinese Characteristics for a alleviation, elderly care, community, education, medical New Era, we thoroughly implemented the guiding principles care and other fields, and went all out to provide financial of the 19th National Party Congress, the second, third and support to poverty alleviation. -

Fantasia Holdings Group Co., Limited 花樣年控股集團有限公司 (Incorporated in Cayman Islands with Limited Liability) (Stock Code: 1777)

Hong Kong Exchanges and Clearing Limited and The Stock Exchange of Hong Kong Limited take no responsibility for the contents of this announcement, make no representation as to its accuracy or completeness and expressly disclaim any liability whatsoever for any loss howsoever arising from or in reliance upon the whole or any part of the contents of this announcement. This announcement is not for distribution, directly or indirectly, in or into the United States. This announcement and the information contained herein does not constitute or form part of an offer to purchase, subscribe or sell securities in the United States. Securities may not be offered or sold in the United States unless registered pursuant to the U.S. Securities Act of 1933, as amended (the “Securities Act”), or pursuant to an applicable exemption from such registration requirements. Any public offering of securities to be made in the United States will be made by means of a prospectus that will contain detailed information about the Company and management, as well as financial statements. The securities referred to herein have not been and will not be registered under the Securities Act and no public offering of securities will be made in the United States. The securities described in this announcement will be sold in accordance with all applicable laws and regulations. No money, securities or other consideration is being solicited by this announcement or the information contained herein and, if sent in response to this announcement or the information contained herein, will not be accepted. Fantasia Holdings Group Co., Limited 花樣年控股集團有限公司 (Incorporated in Cayman Islands with limited liability) (Stock Code: 1777) OVERSEAS REGULATORY ANNOUNCEMENT This overseas regulatory announcement is issued pursuant to Rule 13.10B of the Rules Governing the Listing of Securities (the “Listing Rules”) on The Stock Exchange of Hong Kong Limited (the “Stock Exchange”). -

Chinese Banks' Capital Issuance

Strictly Private and Confidential Chinese Banks’ Capital Issuance September 2013 – February 2014 Offer Size Issue Date Bank Offer Type (US$m) % of Total Equity Offerings 51.7% 07-Jan-14 Ping An Bank (1) Additional Equity Offering 2,443 11.3% 13-Dec-13 China Everbright Bank H Shares Equity Offering 3,205 14.8% 20-Nov-13 Chongqing Rural Commercial Bank Additional Equity Offering 64 0.3% 19-Sep-13 China Merchants Bank Additional Equity Offering 5,502 25.4% IPOs 19.5% 12-Dec-13 China Cinda Asset Management IPO 2,500 11.5% 31-Oct-13 Bank of Chongqing IPO 548 2.5% 11-Nov-13 Huishang Bank Corp IPO 1,188 5.5% Debt Markets 28.7% 24-Jan-14 Bank of Jinzhou Tier-2 Sub. Notes due 2024 246 1.1% 09-Jan-14 Bank of China (London) Notes due 2017 409 1.9% 10-Dec-13 Agricultural Bank of China Notes due 2018 500 2.3% 27-Nov-13 Ping An Insurance Convertible Bond due 2019 4,270 19.7% 08-Nov-13 China Citic Bank Tier-2 Sub. Notes due 2024 300 1.4% 02-Oct-13 ICBC (Asia) Tier-2 Sub. Notes due 2023 500 2.3% Total 21,675 Note: (1) Ping An Bank raised US$2.4bn by selling stock to Ping An Insurance, its main shareholder, which raised its stake in Ping An Bank to 59.0% from 52.4% 1 Merchant Banking Innovation Strictly Private and Confidential Chinese Banks’ Capital Needs September 2013 – February 2014 Selected Board Approved New Issuance (2014-2016) (1) (2) NPL Ratios for Chinese Commercial Banks (3) ICBC: up to c. -

Issuance Overpricing of China's Corporate Debt Securities

Internet Appendix for “Issuance Overpricing of China’s Corporate Debt Securities” Yi Ding Wei Xiong Jinfan Zhang In this Internet Appendix, we report the following figures, tables, and additional analyses omitted from the main paper. Fig. A1 depicts debt security issuance across the interbank market and the exchange market from 2009 to 2019. In Table A1, we list the 68 licensed underwriters in the interbank market at the end of 2019. Information on underwriters is obtained from NAFMII. In Table A2, we summarize overpricing for CP and MTNs separately for both before and after the rebate ban period. Although the magnitude declined after the ban for both CP and MTNs, overpricing remains statistically significantly. Taken together, we find significant overpricing in all these issuance categories. In Table A3, we report summary statistics of issuance overpricing by using excess returns of the first secondary-market trading day as the overpricing measure. The table shows that the overpricing is robust across time, debt securities, and issuers with different characteristics, consistent with Table 3 in the main paper. In Tables A4 and A5, we conduct difference-in-difference analyses to examine how the underwriter rebate ban affects the excess return across different issuers and across different underwriters. Consistent with results in Tables 5 and 6 of the main paper from using the yield-spread measure, these tables show that after the ban, the drop in overpricing is significantly greater for securities issued by central SOEs than for those issued by other firms, and the drop in overpricing is significantly smaller for issuances underwritten by the Big Four banks. -

中國人壽保險股份有限公司 China Life Insurance Company

Hong Kong Exchanges and Clearing Limited and The Stock Exchange of Hong Kong Limited take no responsibility for the contents of this announcement, make no representation as to its accuracy or completeness and expressly disclaim any liability whatsoever for any loss howsoever arising from or in reliance upon the whole or any part of the contents of this announcement. CHINA LIFE中國人壽保險股份有限公司 INSURANCE COMPANY LIMITED (A joint stock limited company incorporated in the People’s Republic of China with limited liability) (Stock Code: 2628) SUMMARY OF SOLVENCY QUARTERLY REPORT OF INSURANCE COMPANY NOTE (SECOND QUARTER OF 2020) 1. BASIC INFORMATION (1) Basic Information of the Company Name of the Company in Chinese: 中國人壽保險股份有限公司 Name of the Company in English: China Life Insurance Company Limited Legal Representative: Wang Bin Registered Address: 16 Financial Street, Xicheng District, Beijing, P.R. China Business Scope: Life, health, accident and other types of personal insurance businesses; reinsurance of the personal insurance businesses; funds management business permitted by national laws and regulations or approved by the State Council; personal insurance services, consulting and agency businesses; sale of securities investment funds; other businesses approved by the national insurance regulatory departments. Business Area: the People’s Republic of China, for the purpose of this report, excluding the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region, Macau Special Administrative Region and Taiwan region (the “PRC”) Notes: 1. This summary of solvency -

China Construction Bank Corporation 2013 Annual Report Builds Modern Living

LIVING BUILDS BUILDS ANNUAL REPORT 2013 REPORT ANNUAL MODERN MODERN CHINA CONSTRUCTION BANK CORPORATION 2013 ANNUAL REPORT BUILDS MODERN LIVING China Construction Bank Corporation, established in October 1954 and headquartered in Beijing, is a leading large-scale joint stock commercial bank in Mainland China with world-renowned reputation. The Bank was listed on Hong Kong Stock Exchange in October 2005 (stock code: 939) and listed on the Shanghai Stock Exchange in September 2007 (stock code: 601939). At the end of 2013, the Bank’s market capitalisation reached US$187.8 billion, ranking 5th among listed banks in the world. With 14,650 branches and sub-branches in Mainland China, the Bank provides services to 3,065,400 corporate customers and 291 million personal customers, and maintains close cooperative relationships with a significant number of high-end customers and leading enterprises of strategic industries in the Chinese economy. The Bank maintains overseas branches in Hong Kong, Singapore, Frankfurt, Johannesburg, Tokyo, Osaka, Seoul, New York, Ho Chi Minh City, Sydney, Melbourne, Taipei and Luxembourg, and owns various subsidiaries, such as CCB Asia, CCB International, CCB London, CCB Russia, CCB Dubai, CCB Europe, CCB Principal Asset Management, CCB Financial Leasing, CCB Trust and CCB Life. The Bank upholds its “customer-centric, market-oriented” business concept, adheres to its development strategy of “integration, multifunction and intensiveness”, and strives to provide customers with premium and all-round modern financial services by accelerating innovation of products, channels and service modes. With a number of core business indicators leading the market, the Bank vigorously promotes the development of emerging businesses including electronic banking, private banking, credit cards, cash management, and pension, while maintaining its traditional businesses advantages in infrastructure and housing finance. -

Reputation of Financial Services

China Report Financial Services of Reputation REPUTATION OF FINANCIAL SERVICES CHINA REPORT Foreword 3 Key Takeaways 4-5 Economic Outlook & Consumer Attitudes 6 Perceptions of Financial Services 9 Attitudes of Risk 13 Consumer Concerns & Choices 14 Financial Sector Facts 17 Asset Management 18 Banking 19 Credit Cards 20 Financial Advisors 21 Fintech 22 Insurance 23 Private Equity 24 Venture Capital 25 Payment Systems 26 Trusted Financial Services Brands 27-29 About North Head 30 Finance is the lifeblood of the real economy. Serving the real economy is the duty of finance. It is the purpose of and the fundamental measure of finance to prevent financial risks. --Xi Jinping, President of PRC, National Financial Work Conference,June 2017 Throughout this survey report: ‘China’ refers to the mainland of the People’s Republic of China, ‘Hong Kong’ refers to Hong Kong Special Administrative Region 2 FOREWORD The 2008 financial crisis was a watershed moment for the reputation of financial services around the world. In North America and Europe it was a period characterised by bail-outs and institutional insolvencies while ushering in the “Global Financial Crisis (GFC)” or “great recession.” However, in November 2008 China launched the “great stimulus”. This ensured that most of East Asia was only tangentially affected by the GFC. Ten years ago China represented 6% of global GDP, while today it is close to 16%. But success was achieved by reliance on debt which impacts the Chinese economy to this day. China’s financial services industry did not suffer the same kind of deep, long-term John Russell reputational damage that occurred in the US and the EU. -

Ar 20 Eng.Pdf

ANNUAL REPORT 2020 Vision To build a first-class commercial bank among peers, with full functionality, diversified businesses and salient features Mission Serving customers Rewarding shareholders Fulfilling the value of employees Making contributions to the society Core values Faithfulness Responsibility Innovation Conscientiousness Introduction of the Bank Established in 1988, China Guangfa Bank is one of the earliest incorporated joint-stock commercial banks in China. The Bank upholds the core values of “faithfulness, responsibility, innovation and conscientiousness”, bears in mind the historic mission of “serving customers, rewarding shareholders, fulfilling the value of employees and making contributions to the society”, practices the service concept of “know each other for you” and strives towards its strategic vision of being “one of the first-class commercial banks in China”. The Bank aims to provide customers with high-quality, efficient and comprehensive financial services. The Bank’s network has expanded to include 46 Tier-1 branches and 882 business outlets in 104 cities at and above the prefecture level in 25 provinces (municipalities and autonomous regions) including Beijing, Tianjin, Hebei, Shanxi, Liaoning, Jilin, Heilongjiang, Shanghai, Jiangsu, Zhejiang, Anhui, Fujian, Jiangxi, Shandong, Henan, Hubei, Hunan, Guangdong, Guangxi, Chongqing, Sichuan, Yunnan, Guizhou, Shaanxi, Xinjiang and the Hong Kong and Macau Special Administrative Regions. The Bank has established correspondent SWIFT authentication partnerships with over 1,174 banking institutions in nearly 100 countries and regions. The Bank’s quality and comprehensive financial services have covered more than 360,000 corporate customers, 48.00 million individual customers, 89.00 million credit card customers and 51.00 million mobile banking customers. -

Zhirui Huang Guangzhou, China | +86 18320060940 | [email protected] | Linkedin.Com/In/Zhirui-Huang

Zhirui Huang Guangzhou, China | +86 18320060940 | [email protected] | linkedin.com/in/zhirui-huang Skills Programming: MATLAB, R, Python, C++, LaTeX Mathematics: Stochastic Calculus, ComPutational Methods, Time Series Analysis Education Boston University, Questrom School of Business Boston, MA M.S. Mathematical Finance & Financial Technology Expected January 2022 • Coursework: Statistics, Programming (R, Python, C++), Stochastic Methods of Asset Pricing Beijing Normal University-Hong Kong BaPtist University United International College Zhuhai, China B.S. Financial Mathematics June 2020 • ScholarshiP: Second Class Award in 2018 - 2019 academic year • Successful Award in Mathematical modeling contest, 2019 • Coursework: Calculus, Linear Algebra, Mathematical Statistics, Ordinary & Partial Differential Equations, Python for Finance, Advanced Probability, C++ Programming Language, Financial Mathematics, Risk Management in Finance Experience Morgan Stanley CaPital International (MSCI) Beijing, China Part-Time Research Assistant for Senior Analyst June 2019 - July 2019 • Reviewed Value-at-Risk (VaR) by applying linear models and examined risk analysis of portfolios (MATLAB) • Evaluated price of American Option with MATLAB, and characterized different oPtions in financial market • Used MATLAB to find the solution of function with Newton-Raphson method China Guangfa Bank Guangzhou, China Intern, Asset Management Department July 2018 - August 2018 • Utilized Wind to collect relevant financial ratios and analyzed financial performance of over 20