How the Tidal Evolution of Hot J Upiters Affects Transit Surveys of Clusters

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Pulsation and Rotation in NGC 6811: the Kepler Short-Cadence Stars

MNRAS 491, 4345–4364 (2020) doi:10.1093/mnras/stz3143 Advance Access publication 2019 November 12 Pulsation and rotation in NGC 6811: the Kepler short-cadence stars E. Rodr´ıguez ,1‹ L. A. Balona ,2‹ M. J. Lopez-Gonz´ alez,´ 1‹ S. Ocando,1 S. Mart´ın-Ruiz1 and C. Rodr´ıguez-Lopez´ 1 Downloaded from https://academic.oup.com/mnras/article-abstract/491/3/4345/5622881 by Universidad de Granada - Biblioteca user on 29 April 2020 1Instituto de Astrof´ısica de Andaluc´ıa, CSIC, PO Box 3004, E-18080 Granada, Spain 2South African Astronomical Observatory, PO Box 9, Observatory, Cape 2735, South Africa Accepted 2019 November 6. Received 2019 November 6; in original form 2019 September 11 ABSTRACT We have analysed a selected sample of 36 Kepler short-cadence stars in the field of NGC 6811. The results reveal that all the targets are variable: two red giant stars with solar-like oscillations, 21 main-sequence pulsators (16 δ Scuti and five γ Doradus stars), and 13 rotating variables. Three new γ Doradus (γ Dor) variables (one is a hot γ Dor star) are detected in this work together with five new rotating variables. An in-depth frequency analysis of the δ Scuti (δ Sct) and γ Dor stars in the sample shows that the frequency spectra are very rich, in particular for the δ Sct-type variables. They present very dense frequency distributions and wide diversity in frequency patterns, even for stars being members of the cluster and with very similar location in the Hertzsprung–Russell (H–R) diagram. -

![The [Y/Mg] Clock Works for Evolved Solar Metallicity Stars ? D](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/5990/the-y-mg-clock-works-for-evolved-solar-metallicity-stars-d-155990.webp)

The [Y/Mg] Clock Works for Evolved Solar Metallicity Stars ? D

Astronomy & Astrophysics manuscript no. clusters_le c ESO 2017 July 28, 2017 The [Y/Mg] clock works for evolved solar metallicity stars ? D. Slumstrup1, F. Grundahl1, K. Brogaard1; 2, A. O. Thygesen3, P. E. Nissen1, J. Jessen-Hansen1, V. Van Eylen4, and M. G. Pedersen5 1 Stellar Astrophysics Centre (SAC). Department of Physics and Astronomy, Aarhus University, Ny Munkegade 120, DK-8000 Aarhus, Denmark e-mail: [email protected] 2 School of Physics and Astronomy, University of Birmingham, Edgbaston, Birmingham B15 2TT, UK 3 California Institute of Technology, 1200 E. California Blvd, MC 249-17, Pasadena, CA 91125, USA 4 Leiden Observatory, Leiden University, 2333CA Leiden, The Netherlands 5 Instituut voor Sterrenkunde, KU Leuven, Celestijnenlaan 200D, 3001 Leuven, Belgium Received 3 July 2017 / Accepted 20 July2017 ABSTRACT Aims. Previously [Y/Mg] has been proven to be an age indicator for solar twins. Here, we investigate if this relation also holds for helium-core-burning stars of solar metallicity. Methods. High resolution and high signal-to-noise ratio (S/N) spectroscopic data of stars in the helium-core-burning phase have been obtained with the FIES spectrograph on the NOT 2:56 m telescope and the HIRES spectrograph on the Keck I 10 m telescope. They have been analyzed to determine the chemical abundances of four open clusters with close to solar metallicity; NGC 6811, NGC 6819, M67 and NGC 188. The abundances are derived from equivalent widths of spectral lines using ATLAS9 model atmospheres with parameters determined from the excitation and ionization balance of Fe lines. Results from asteroseismology and binary studies were used as priors on the atmospheric parameters, where especially the log g is determined to much higher precision than what is possible with spectroscopy. -

![Arxiv:1001.0139V1 [Astro-Ph.SR] 31 Dec 2009 Oadl Gilliland, L](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/4155/arxiv-1001-0139v1-astro-ph-sr-31-dec-2009-oadl-gilliland-l-354155.webp)

Arxiv:1001.0139V1 [Astro-Ph.SR] 31 Dec 2009 Oadl Gilliland, L

Publications of the Astronomical Society of the Pacific Kepler Asteroseismology Program: Introduction and First Results Ronald L. Gilliland,1 Timothy M. Brown,2 Jørgen Christensen-Dalsgaard,3 Hans Kjeldsen,3 Conny Aerts,4 Thierry Appourchaux,5 Sarbani Basu,6 Timothy R. Bedding,7 William J. Chaplin,8 Margarida S. Cunha,9 Peter De Cat,10 Joris De Ridder,4 Joyce A. Guzik,11 Gerald Handler,12 Steven Kawaler,13 L´aszl´oKiss,7,14 Katrien Kolenberg,12 Donald W. Kurtz,15 Travis S. Metcalfe,16 Mario J.P.F.G. Monteiro,9 Robert Szab´o,14 Torben Arentoft,3 Luis Balona,17 Jonas Debosscher,4 Yvonne P. Elsworth,8 Pierre-Olivier Quirion,3,18 Dennis Stello,7 Juan Carlos Su´arez,19 William J. Borucki,20 Jon M. Jenkins,21 David Koch,20 Yoji Kondo,22 David W. Latham,23 Jason F. Rowe,20 and Jason H. Steffen24 arXiv:1001.0139v1 [astro-ph.SR] 31 Dec 2009 –2– ABSTRACT Asteroseismology involves probing the interiors of stars and quantifying their global properties, such as radius and age, through observations of normal modes of oscillation. The technical requirements for conducting asteroseismology in- clude ultra-high precision measured in photometry in parts per million, as well as nearly continuous time series over weeks to years, and cadences rapid enough 1Space Telescope Science Institute, 3700 San Martin Drive, Baltimore, MD 21218, USA; [email protected] 2Las Cumbres Observatory Global Telescope, Goleta, CA 93117, USA 3Department of Physics and Astronomy, Aarhus University, DK-8000 Aarhus C, Denmark 4Instituut voor Sterrenkunde, K.U.Leuven, Celestijnenlaan 200 D, 3001, Leuven, Belgium 5Institut d’Astrophysique Spatiale, Universit´eParis XI, Bˆatiment 121, 91405 Orsay Cedex, France 6Astronomy Department, Yale University, P.O. -

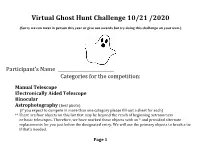

Ghost Hunt Challenge 2020

Virtual Ghost Hunt Challenge 10/21 /2020 (Sorry we can meet in person this year or give out awards but try doing this challenge on your own.) Participant’s Name _________________________ Categories for the competition: Manual Telescope Electronically Aided Telescope Binocular Astrophotography (best photo) (if you expect to compete in more than one category please fill-out a sheet for each) ** There are four objects on this list that may be beyond the reach of beginning astronomers or basic telescopes. Therefore, we have marked these objects with an * and provided alternate replacements for you just below the designated entry. We will use the primary objects to break a tie if that’s needed. Page 1 TAS Ghost Hunt Challenge - Page 2 Time # Designation Type Con. RA Dec. Mag. Size Common Name Observed Facing West – 7:30 8:30 p.m. 1 M17 EN Sgr 18h21’ -16˚11’ 6.0 40’x30’ Omega Nebula 2 M16 EN Ser 18h19’ -13˚47 6.0 17’ by 14’ Ghost Puppet Nebula 3 M10 GC Oph 16h58’ -04˚08’ 6.6 20’ 4 M12 GC Oph 16h48’ -01˚59’ 6.7 16’ 5 M51 Gal CVn 13h30’ 47h05’’ 8.0 13.8’x11.8’ Whirlpool Facing West - 8:30 – 9:00 p.m. 6 M101 GAL UMa 14h03’ 54˚15’ 7.9 24x22.9’ 7 NGC 6572 PN Oph 18h12’ 06˚51’ 7.3 16”x13” Emerald Eye 8 NGC 6426 GC Oph 17h46’ 03˚10’ 11.0 4.2’ 9 NGC 6633 OC Oph 18h28’ 06˚31’ 4.6 20’ Tweedledum 10 IC 4756 OC Ser 18h40’ 05˚28” 4.6 39’ Tweedledee 11 M26 OC Sct 18h46’ -09˚22’ 8.0 7.0’ 12 NGC 6712 GC Sct 18h54’ -08˚41’ 8.1 9.8’ 13 M13 GC Her 16h42’ 36˚25’ 5.8 20’ Great Hercules Cluster 14 NGC 6709 OC Aql 18h52’ 10˚21’ 6.7 14’ Flying Unicorn 15 M71 GC Sge 19h55’ 18˚50’ 8.2 7’ 16 M27 PN Vul 20h00’ 22˚43’ 7.3 8’x6’ Dumbbell Nebula 17 M56 GC Lyr 19h17’ 30˚13 8.3 9’ 18 M57 PN Lyr 18h54’ 33˚03’ 8.8 1.4’x1.1’ Ring Nebula 19 M92 GC Her 17h18’ 43˚07’ 6.44 14’ 20 M72 GC Aqr 20h54’ -12˚32’ 9.2 6’ Facing West - 9 – 10 p.m. -

A Basic Requirement for Studying the Heavens Is Determining Where In

Abasic requirement for studying the heavens is determining where in the sky things are. To specify sky positions, astronomers have developed several coordinate systems. Each uses a coordinate grid projected on to the celestial sphere, in analogy to the geographic coordinate system used on the surface of the Earth. The coordinate systems differ only in their choice of the fundamental plane, which divides the sky into two equal hemispheres along a great circle (the fundamental plane of the geographic system is the Earth's equator) . Each coordinate system is named for its choice of fundamental plane. The equatorial coordinate system is probably the most widely used celestial coordinate system. It is also the one most closely related to the geographic coordinate system, because they use the same fun damental plane and the same poles. The projection of the Earth's equator onto the celestial sphere is called the celestial equator. Similarly, projecting the geographic poles on to the celest ial sphere defines the north and south celestial poles. However, there is an important difference between the equatorial and geographic coordinate systems: the geographic system is fixed to the Earth; it rotates as the Earth does . The equatorial system is fixed to the stars, so it appears to rotate across the sky with the stars, but of course it's really the Earth rotating under the fixed sky. The latitudinal (latitude-like) angle of the equatorial system is called declination (Dec for short) . It measures the angle of an object above or below the celestial equator. The longitud inal angle is called the right ascension (RA for short). -

The Kepler Characterization of the Variability Among A- and F-Type Stars

Astronomy & Astrophysics manuscript no. Uytterhoeven˙KeplerAFstars c ESO 2018 August 21, 2018 The Kepler characterization of the variability among A- and F-type stars I. General overview K. Uytterhoeven1,2,3, A. Moya4, A. Grigahc`ene5, J.A. Guzik6, J. Guti´errez-Soto7,8,9, B. Smalley10, G. Handler11,12, L.A. Balona13, E. Niemczura14, L. Fox Machado15, S. Benatti16,17, E. Chapellier18, A. Tkachenko19, R. Szab´o20, J.C. Su´arez7, V. Ripepi21, J. Pascual7, P. Mathias22, S. Mart´ın-Ru´ız7, H. Lehmann23, J. Jackiewicz24, S. Hekker25,26, M. Gruberbauer27,11, R.A. Garc´ıa1, X. Dumusque5,28, D. D´ıaz-Fraile7, P. Bradley29, V. Antoci11, M. Roth2, B. Leroy8, S.J. Murphy30, P. De Cat31, J. Cuypers31, H. Kjeldsen32, J. Christensen-Dalsgaard32 , M. Breger11,33, A. Pigulski14, L.L. Kiss20,34, M. Still35, S.E. Thompson36, and J. Van Cleve36 (Affiliations can be found after the references) Received / Accepted ABSTRACT Context. The Kepler spacecraft is providing time series of photometric data with micromagnitude precision for hundreds of A-F type stars. Aims. We present a first general characterization of the pulsational behaviour of A-F type stars as observed in the Kepler light curves of a sample of 750 candidate A-F type stars, and observationally investigate the relation between γ Doradus (γ Dor), δ Scuti (δ Sct), and hybrid stars. Methods. We compile a database of physical parameters for the sample stars from the literature and new ground-based observations. We analyse the Kepler light curve of each star and extract the pulsational frequencies using different frequency analysis methods. -

LIST of PUBLICATIONS Aryabhatta Research Institute of Observational Sciences ARIES (An Autonomous Scientific Research Institute

LIST OF PUBLICATIONS Aryabhatta Research Institute of Observational Sciences ARIES (An Autonomous Scientific Research Institute of Department of Science and Technology, Govt. of India) Manora Peak, Naini Tal - 263 129, India (1955−2020) ABBREVIATIONS AA: Astronomy and Astrophysics AASS: Astronomy and Astrophysics Supplement Series ACTA: Acta Astronomica AJ: Astronomical Journal ANG: Annals de Geophysique Ap. J.: Astrophysical Journal ASP: Astronomical Society of Pacific ASR: Advances in Space Research ASS: Astrophysics and Space Science AE: Atmospheric Environment ASL: Atmospheric Science Letters BA: Baltic Astronomy BAC: Bulletin Astronomical Institute of Czechoslovakia BASI: Bulletin of the Astronomical Society of India BIVS: Bulletin of the Indian Vacuum Society BNIS: Bulletin of National Institute of Sciences CJAA: Chinese Journal of Astronomy and Astrophysics CS: Current Science EPS: Earth Planets Space GRL : Geophysical Research Letters IAU: International Astronomical Union IBVS: Information Bulletin on Variable Stars IJHS: Indian Journal of History of Science IJPAP: Indian Journal of Pure and Applied Physics IJRSP: Indian Journal of Radio and Space Physics INSA: Indian National Science Academy JAA: Journal of Astrophysics and Astronomy JAMC: Journal of Applied Meterology and Climatology JATP: Journal of Atmospheric and Terrestrial Physics JBAA: Journal of British Astronomical Association JCAP: Journal of Cosmology and Astroparticle Physics JESS : Jr. of Earth System Science JGR : Journal of Geophysical Research JIGR: Journal of Indian -

Asteroseismic Inferences on Red Giants in Open Clusters NGC 6791, NGC 6819, and NGC 6811 Using Kepler

A&A 530, A100 (2011) Astronomy DOI: 10.1051/0004-6361/201016303 & c ESO 2011 Astrophysics Asteroseismic inferences on red giants in open clusters NGC 6791, NGC 6819, and NGC 6811 using Kepler S. Hekker1,2, S. Basu3, D. Stello4, T. Kallinger5, F. Grundahl6,S.Mathur7,R.A.García8, B. Mosser9,D.Huber4, T. R. Bedding4,R.Szabó10, J. De Ridder11,W.J.Chaplin2, Y. Elsworth2,S.J.Hale2, J. Christensen-Dalsgaard6 , R. L. Gilliland12, M. Still13, S. McCauliff14, and E. V. Quintana15 1 Astronomical Institute “Anton Pannekoek”, University of Amsterdam, Science Park 904, 1098 XH Amsterdam, The Netherlands e-mail: [email protected] 2 School of Physics and Astronomy, University of Birmingham, Edgbaston, Birmingham B15 2TT, UK 3 Department of Astronomy, Yale University, PO Box 208101, New Haven CT 06520-8101, USA 4 Sydney Institute for Astronomy (SIfA), School of Physics, University of Sydney, NSW 2006, Australia 5 Department of Physics and Astronomy, University of British Colombia, 6224 Agricultural Road, Vancouver, BC V6T 1Z1, Canada 6 Department of Physics and Astronomy, Building 1520, Aarhus University, 8000 Aarhus C, Denmark 7 High Altitude Observatory, NCAR, PO Box 3000, Boulder, CO 80307, USA 8 Laboratoire AIM, CEA/DSM-CNRS, Université Paris 7 Diderot, IRFU/SAp, Centre de Saclay, 91191 Gif-sur-Yvette, France 9 LESIA, UMR8109, Université Pierre et Marie Curie, Université Denis Diderot, Observatoire de Paris, 92195 Meudon Cedex, France 10 Konkoly Observatory of the Hungarian Academy of Sciences, Konkoly Thege Miklós út 15-17, 1121 Budapest, Hungary 11 Instituut voor Sterrenkunde, K.U. Leuven, Celestijnenlaan 200D, 3001 Leuven, Belgium 12 Space Telescope Science Institute, 3700 San Martin Drive, Baltimore, MD 21218, USA 13 Bay Area Environmental Research Institute/Nasa Ames Research Center, Moffett Field, CA 94035, USA 14 Orbital Sciences Corporation/Nasa Ames Research Center, Moffett Field, CA 94035, USA 15 SETI Institute/Nasa Ames Research Center, Moffett Field, CA 94035, USA Received 13 December 2010 / Accepted 19 April 2011 ABSTRACT Context. -

WIYN Open Cluster Study. XXIV. Stellar Radial-Velocity Measurements in NGC 6819

WIYN Open Cluster Study. XXIV. Stellar Radial-Velocity Measurements in NGC 6819 K. Tabetha Hole1,2 ([email protected]) Aaron M. Geller1,2 ([email protected]) Robert D. Mathieu1,2 ([email protected]) Imants Platais3 ([email protected]) Søren Meibom1,2,4 ([email protected]) and David W. Latham4 ([email protected]) ABSTRACT We present the current results from our ongoing radial-velocity survey of the intermediate-age (2.4 Gyr) open cluster NGC 6819. Using both newly observed and other available photometry and astrometry we define a primary target sample of 1454 stars that includes main-sequence, subgiant, giant, and blue straggler stars, spanning a magnitude range of 11≤V ≤16.5 and an approximate mass range of 1.1to1.6 M⊙. Our sample covers a 23 arcminute (13 pc) square field of view centered on the cluster. We have measured 6571 radial velocities for an unbiased sample of 1207 stars in the direction of the open cluster NGC 6819, with a single-measurement precision of 0.4km s−1 for most narrow-lined stars. We use our radial-velocity data to calculate membership probabilities for stars with ≥ 3 measurements, providing the first comprehensive membership study of the cluster core that includes stars from the giant branch through the upper main sequence. We identify 475 cluster members. Additionally, we identify velocity-variable systems, all of which are likely hard binaries that dynamically power the cluster. Using our single cluster members, we find a cluster radial velocity of 2.33 ± 0.05 km s−1. -

Proto-Planetary Nebula Observing Guide

Proto-Planetary Nebula Observing Guide www.reinervogel.net RA Dec CRL 618 Westbrook Nebula 04h 42m 53.6s +36° 06' 53" PK 166-6 1 HD 44179 Red Rectangle 06h 19m 58.2s -10° 38' 14" V777 Mon OH 231.8+4.2 Rotten Egg N. 07h 42m 16.8s -14° 42' 52" Calabash N. IRAS 09371+1212 Frosty Leo 09h 39m 53.6s +11° 58' 54" CW Leonis Peanut Nebula 09h 47m 57.4s +13° 16' 44" Carbon Star with dust shell M 2-9 Butterfly Nebula 17h 05m 38.1s -10° 08' 33" PK 10+18 2 IRAS 17150-3224 Cotton Candy Nebula 17h 18m 20.0s -32° 27' 20" Hen 3-1475 Garden-sprinkler Nebula 17h 45m 14. 2s -17° 56' 47" IRAS 17423-1755 IRAS 17441-2411 Silkworm Nebula 17h 47m 13.5s -24° 12' 51" IRAS 18059-3211 Gomez' Hamburger 18h 09m 13.3s -32° 10' 48" MWC 922 Red Square Nebula 18h 21m 15s -13° 01' 27" IRAS 19024+0044 19h 05m 02.1s +00° 48' 50.9" M 1-92 Footprint Nebula 19h 36m 18.9s +29° 32' 50" Minkowski's Footprint IRAS 20068+4051 20h 08m 38.5s +41° 00' 37" CRL 2688 Egg Nebula 21h 02m 18.8s +36° 41' 38" PK 80-6 1 IRAS 22036+5306 22h 05m 30.3s +53° 21' 32.8" IRAS 23166+1655 23h 19m 12.6s +17° 11' 33.1" Southern Objects ESO 172-7 Boomerang Nebula 12h 44m 45.4s -54° 31' 11" Centaurus bipolar nebula PN G340.3-03.2 Water Lily Nebula 17h 03m 10.1s -47° 00' 27" PK 340-03 1 IRAS 17163-3907 Fried Egg Nebula 17h 19m 49.3s -39° 10' 37.9" Finder charts measure 20° (with 5° circle) and 5° (with 1° circle) and were made with Cartes du Ciel by Patrick Chevalley (http://www.ap-i.net/skychart) Images are DSS Images (blue plates, POSS II or SERCJ) and measure 30’ by 30’ (http://archive.stsci.edu/cgi- bin/dss_plate_finder) and STScI Images (Hubble Space Telescope) Downloaded from www.reinervogel.net version 12/2012 DSS images copyright notice: The Digitized Sky Survey was produced at the Space Telescope Science Institute under U.S. -

Open Clusters

Open Clusters Open clusters (also known as galactic clusters) are of tremendous importance to the science of astronomy, if not to astrophysics and cosmology generally. Star clusters serve as the "laboratories" of astronomy, with stars now all at nearly the same distance and all created at essentially the same time. Each cluster thus is a running experiment, where we can observe the effects of composition, age, and environment. We are hobbled by seeing only a snapshot in time of each cluster, but taken collectively we can understand their evolution, and that of their included stars. These clusters are also important tracers of the Milky Way and other parent galaxies. They help us to understand their current structure and derive theories of the creation and evolution of galaxies. Just as importantly, starting from just the Hyades and the Pleiades, and then going to more distance clusters, open clusters serve to define the distance scale of the Milky Way, and from there all other galaxies and the entire universe. However, there is far more to the study of star clusters than that. Anyone who has looked at a cluster through a telescope or binoculars has realized that these are objects of immense beauty and symmetry. Whether a cluster like the Pleiades seen with delicate beauty with the unaided eye or in a small telescope or binoculars, or a cluster like NGC 7789 whose thousands of stars are seen with overpowering wonder in a large telescope, open clusters can only bring awe and amazement to the viewer. These sights are available to all. -

Str ¨Omgren Survey for Asteroseismology and Galactic

The Astrophysical Journal, 787:110 (25pp), 2014 June 1 doi:10.1088/0004-637X/787/2/110 C 2014. The American Astronomical Society. All rights reserved. Printed in the U.S.A. STROMGREN¨ SURVEY FOR ASTEROSEISMOLOGY AND GALACTIC ARCHAEOLOGY: LET THE SAGA BEGIN∗ L. Casagrande1,14, V. Silva Aguirre2, D. Stello3, D. Huber4,5, A. M. Serenelli6, S. Cassisi7, A. Dotter1, A. P. Milone1, S. Hodgkin8,A.F.Marino1, M. N. Lund2, A. Pietrinferni7,M.Asplund1, S. Feltzing9, C. Flynn10, F. Grundahl2,P.E.Nissen2,R.Schonrich¨ 11,12,15, K. J. Schlesinger1, and W. Wang13 1 Research School of Astronomy and Astrophysics, Mount Stromlo Observatory, The Australian National University, Canberra, ACT 2611, Australia; [email protected] 2 Stellar Astrophysics Centre, Department of Physics and Astronomy, Aarhus University, Ny Munkegade 120, DK-8000 Aarhus C, Denmark 3 Sydney Institute for Astronomy (SIfA), School of Physics, University of Sydney, Sydney, NSW 2006, Australia 4 NASA Ames Research Center, Moffett Field, CA 94035, USA 5 SETI Institute, 189 Bernardo Avenue, Mountain View, CA 94043, USA 6 Institute of Space Sciences (IEEC-CSIC), Campus UAB, Fac. Ciencies,´ Torre C5 parell 2, E-08193 Bellaterra, Spain 7 INAF-Osservatorio Astronomico di Collurania, via Maggini, I-64100 Teramo, Italy 8 Institute of Astronomy, Madingley Road, Cambridge CB3 0HA, UK 9 Lund Observatory, Department of Astronomy and Theoretical Physics, P.O. Box 43, SE-22100 Lund, Sweden 10 Centre for Astrophysics and Supercomputing, Swinburne University of Technology, Hawthorn, VIC 3122, Australia