Solitary Elephants Injapan

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Arts, Parks, Health

-.. "'/r. - ~ .ct~ January 21, 2009 Arts, Parks, Health and Aging Committee c/o City Clerk 200 S. Spring Street St., Room 303 Los Angeles, CA 90012-413 7 Attention: Erika Pulst, Legislative Coordinator "Nurturing wildlife and enriching RE: STATUS OF ELEPHANT EXHIBITS IN THE UNITED STATES RELATIVE the human TO MOTION (CARDENAS-ROSENDAHL-ALARCON C.F. 08-2850) experience Los Angeles Zoo This report was prepared in response to the City Council's action on December 3, 2008, 5333 Zoo Drive which referred various issues contained in the Motion (Cardenas-Rosendahl-Alarcon) Los Angeles California 90027 relative to the Pachyderm Forest project at the Los Angeles Zoo back to the Arts, Parks, 323/644-4200 Health, and Aging Committee. This report specifically addresses "the status of elephant Fax 323/662-9786 http://www.lazoo.org exhibits that have closed and currently do house elephants on the zoos premise throughout the United States". Antonio R. Villaraigosa Mayor The Motion specifically lists 12 cities that have closed their elephant exhibits and six Tom LaBonge zoos that plan on closing or phasing out their exhibits. However, in order to put this Council Member information into the correct context, particularly as it relates to "joining these 4'h District progressive cities and permanently close the exhibit at the Los Angeles Zoo", the City Zoo Commissioners Council should also be informed on all Association of Zoos and Aquarium (AZA) zoos Shelby Kaplan Sloan in the United States that currently exhibit elephants and the commitment to their President programs now and into the future. Karen B. -

The Zoos of Texas

Among the array of African birds are White-breasted Cormorants, breeding groups of Kori and Red-crested The Zoos of Texas - 2003 Bustards, a Goliath Heron, breeding Saddle-billed and Marabou Storks, Text by Josef Lindholm /II Keeper, Birds and Small Mammals, breeding Eared and Hooded Vultures, Cameron Park Zoo, Waco, Texas Erckel's Francolins, the only East Photos by Natalie Mashburn Lindholm, Mammal Keeper, African Green Pigeons (Treron calva) Cameron Park Zoo, Waco, Texas in the U.S., more than thirty Fischer's [Editor's Note: We bird lovers have Trumpeter Hornbills and Green Wood Lovebirds, breeding African Ring always been delighted with zoos because they Hoopoes have also been prolific. A necked parakeets, a large and prolific usually contain a large and beautiful assort walk-through aviary shares a fascinat flock of speckled Mousebirds, a Gray ment of birds - quite often birds we seldom ing building with aquaria and small headed Kingfisher, Bearded Barbets, see in private aviculture. With this in mind, mammal and reptile displays, and is and a Black-winged Bishop. Josef Lindholm has kindly put together an home to several avicultural rarities. In Zoo North one may admire overview of the zoos of Texas. Hopefully, According to ISIS, the Gray-backed Ocellated Turkeys, Beautiful, Black those of you who are driving to the convention Sparrow Lark (Eremopterix verticalis), naped and Wompoo Fruit Pigeons, will take time to visit the zoos along your way. at Abilene more than a decade, is the Blue-crowned Hanging Parrots, Blue Due to space constraints, it may take several only one exhibited anywhere. -

Sustaining Our State's Diverse Fish and Wildlife Resources: Conservation Delivery Through the Recovering America's Wildl

Sustaining Our State’s Diverse Fish and Wildlife Resources Conservation delivery through the Recovering America’s Wildlife Act 2019 This report and recommendations were prepared by the TPWD Texas Alliance for America’s Fish and Wildlife Task Force, comprised of the following members: Tim Birdsong (TPWD Inland Fisheries Division) Greg Creacy (TPWD State Parks Division) John Davis (TPWD Wildlife Division) Kevin Davis (TPWD Law Enforcement Division) Dakus Geeslin (TPWD Coastal Fisheries Division) Tom Harvey (TPWD Communications Division) Richard Heilbrun (TPWD Wildlife Division) Chris Mace (TPWD Coastal Fisheries Division) Ross Melinchuk (TPWD Executive Office) Michael Mitchell (TPWD Law Enforcement Division) Shelly Plante (TPWD Communications Division) Johnnie Smith (TPWD Communications Division) Acknowledgements: The TPWD Texas Alliance for America’s Fish and Wildlife Task Force would like to express gratitude to Kim Milburn, Larry Sieck, Olivia Schmidt, and Jeannie Muñoz for their valuable support roles during the development of this report. CONTENTS 1 The Opportunity Background 2 The Rich Resources of Texas 3 The People of Texas 4 Sustaining Healthy Water and Ecosystems Law Enforcement 5 Outdoor Recreation 6 TPWD Allocation Strategy 16 Call to Action 17 Appendix 1: List of Potential Conservation Partners The Opportunity Background Passage of the Recovering America's Our natural resources face many challeng- our lands and waters. The growing num- Wildlife Act would mean more than $63 es in the years ahead. As more and more ber of Texans seeking outdoor experiences million in new dollars each year for Texas, Texans reside in urban areas, many are will call for new recreational opportunities. transforming efforts to conserve and re- becoming increasingly detached from any Emerging and expanding energy technol- store more than 1,300 nongame fish and meaningful connection to nature or the ogies will require us to balance new en- wildlife species of concern here in the outdoors. -

Texas State Travel Guide Media Brochure

STATE TRAVEL GUIDE EDITORIAL PROFILE AND MARKET INFORMATION EDITORIAL PROFILE GETTING AROUND TRAVEL INFORMATION his year, the Texas Department of Transportation celebrates 100 years of helping drivers safely travel the state. On April 4, 1917, Gov. James Ferguson signed House Bill 2, establishing the State Highway Department and creating T a commission and engineer position to oversee state highway construction and state vehicle registrations. Since then, TxDOT has been building the state highway system (1918) and urban expressways (1951), helping visitors find their way around the When Cuatro, age 7, went state (1936), publishing Texas Highways as a state travel magazine (1974), encourag- fishing with his family this ing people to pick up trash along highways (1985), and telling them “Don’t mess with year, he had no idea what he might catch. And he never, ever, in his wildest dreams thought Texas” (1986). TxDOT is looking forward to what the next 100-plus years will bring. it would be this whopper, a 40lb, technicolor Dorado DRIVETEXAS™—This is the Texas Department of Transportation’s highway conditions taken of the license plate and the bill is mailed (aka, to the address associated with the plate. The just off the coast of Corpus Christi. Mahi Mahi) that he reeled in in for mation service. Travelers can visit CLIMATE —Texas terrain includes arid desert drivetexas.org to view an interactive high- bill may contain an administrative charge in mountains, limestone hills, rich farmland, Memories are most definitely made here in the way map displaying construction areas, addition to the toll fee. Rental car drivers grasslands, marshes and deep forests. -

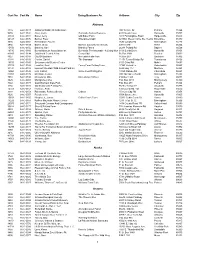

Cert No Name Doing Business As Address City Zip 1 Cust No

Cust No Cert No Name Doing Business As Address City Zip Alabama 3316 64-C-0117 Alabama Wildlife Rehabilitation 100 Terrace Dr Pelham 35124 9655 64-C-0141 Allen, Keith Huntsville Nature Preserve 431 Clouds Cove Huntsville 35803 33483 64-C-0181 Baker, Jerry Old Baker Farm 1041 Farmingdale Road Harpersville 35078 44128 64-C-0196 Barber, Peter Enterprise Magic 621 Boll Weevil Circle Ste 16-202 Enterprise 36330 3036 64-C-0001 Birmingham Zoo Inc 2630 Cahaba Rd Birmingham 35223 2994 64-C-0109 Blazer, Brian Blazers Educational Animals 230 Cr 880 Heflin 36264 15456 64-C-0156 Brantley, Karl Brantley Farms 26214 Pollard Rd Daphne 36526 16710 64-C-0160 Burritt Museum Association Inc Burritt On The Mountain - A Living Mus 3101 Burritt Drive Huntsville 35801 42687 64-C-0194 Cdd North Central Al Inc Camp Cdd Po Box 2091 Decatur 35602 3027 64-C-0008 City Of Gadsden Noccalula Falls Park Po Box 267 Gadsden 35902 41384 64-C-0193 Combs, Daniel The Barnyard 11453 Turner Bridge Rd Tuscaloosa 35406 19791 64-C-0165 Environmental Studies Center 6101 Girby Rd Mobile 36693 37785 64-C-0188 Lassitter, Scott Funny Farm Petting Farm 17347 Krchak Ln Robertsdale 36567 33134 64-C-0182 Lookout Mountain Wild Animal Park Inc 3593 Hwy 117 Mentone 35964 12960 64-C-0148 Lott, Carlton Uncle Joes Rolling Zoo 13125 Malone Rd Chunchula 36521 22951 64-C-0176 Mc Wane Center 200 19th Street North Birmingham 35203 7051 64-C-0185 Mcclelland, Mike Mcclellands Critters P O Box 1340 Troy 36081 3025 64-C-0003 Montgomery Zoo P.O. -

Eliminating%Longcrange%And%“Dangerous”%% Wild%Animals

Fall$ Fall$ 08! ! ! August$$ ! ! 2012% ! ! ! ! Eliminating%! LongCrange%and%“Dangerous”%% ! Wild%Animals%from%Entertainment%! ! Demonstrations%! in%New%York%State%% ! ! ! % ! ! ! ! ! Pace%University%Academy%for%Applied%Environmental%Studies%! ! &%the%Committee%to%Ban%Wild%and%Exotic%Animal%Acts! % ! ! ! ! Michelle!D.!Land,!J.D.1! Pace!University!Academy!for!Applied!Environmental!Studies! 901!Bedford!Road!! Pleasantville,!NY!10570! (914)!773L3091! [email protected]!! ! Committee!to!Ban!Wild!and!Exotic!Animal!Acts! Bob!Funck! Neil!Platt! Louise!Simmons! ! ! ! ! ! ! !!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!! 1!With!assistance!from!Pace!University!research!assistants,!Caroline!Craig,!Jessica!Goldstein,!Emilie! Guidat,!Meghan!C.!Marshall!and!Cheri!Neal.!!!! ! TABLE!OF!CONTENTS! ! I. SYNOPSIS!(4)! ! II. ISSUES!WITH!“DANGEROUS”!WILD!ANIMALS!IN!ENTERTAINMENT! ! a. Traveling!Circuses!and!Animal!Confinement!(5)! ! b. Training!LongKRange!Wild!Animal!Performers!(7)! ! c. Consequences!of!Physiological!Stressors!in!Wild!CaPtive!Animals!(9)! ! d. Animal!Welfare!Act!and!Regulation!of!Wild!Animals!(13)! ! e. Public!Safety!Risk!(14)! ! f. Lack!of!Educational!Value!(16)! ! III. WORLDWIDE!AND!DOMESTIC!TREND!TOWARD!NONLANIMAL!CIRCUSES! ! a. History!of!the!Circus:!A!Trend!Toward!Human!Performance!Entertainment! (18)! ! b. Today’s!Circuses!(19)! ! c. Zoos!Phasing!Out!Elephant!Exhibits!(20)! ! d. Primate!SPecific!Bans!(21)! ! e. International!Legislation!to!Restrict!Use!of!Wild!Animals!in!Entertainment! (21)! ! f. United!States!Legislation!to!Restrict!Use!of!Wild!Animals!in!Entertainment! (23)! ! IV. PROPOSED!ACTION!AND!IMPACTS! ! a. Proposed!Legislation!(25)! ! b. Animal!Circuses!RePlaced!by!NonKAnimal!Circuses!(27)! ! c. Economic!Impact!of!Eliminating!LongKRange!Wild!Animals!from!Circuses! (27)! ! V. CONCLUSION!(29)! ! ! 2! ! VI. APPENDICES! ! A. !CIRCUS!CITATIONS!AND!INCIDENTS!(PETA)! ! B. !CIRCUS!ANIMAL!INCIDENTS!(PETA)!! ! C. LETTER!FROM!BLAYNE!DOYLE!TO!WESTCHESTER!COUNTY!BOARD!OF! LEGISLATORS!! ! D. -

Animal Welfare

aQL35 .054 USDA Animal Welfare: United States Department of List of Licensed Agriculture Animal and Plant Health Exhibitors and Inspection Service APHIS 41-35-069 Registered Exhibitors Fiscal Year 2001 Licensed Exhibitors Cust No Cert No Name Doing Business As Address City Zip Alabama 3336 64-C-0120 Isenring, Larrie Pet-R-Pets 25236 Patterson Rd. Robertsdale 36567 7788 64-C-0144 Alabama Division Of Wildlife Wildlife Section Montgomery 36130 3316 64-C-0117 Alabama Wildlife Rehabilitation lOOterrace Dr Pelham 35124 9655 64-C-0141 Allen, Keith Huntsville Nature Preserve 431 Clouds Cove Huntsville 35803 12722 64-C-0149 Beebe & Swearingen, Lie. A Little Touch Of Country 41500 Whitehouse Fork Rd Bay Minette 36507 3036 64-C-0001 Birmingham Zoo, Inc. 2630 Cahaba Rd Birmingham 35223 2994 64-C-0109 Blazer, Brian Blazer's Educational Animals 230 Cr 880 Heflin 36264 3020 64-C-0107 Buds 'N' Blossoms. Inc. 5881 U.S. 431 North Dothan 36303 6623 64-C-0128 Camp Ascca 5278 Camp Ascca Drive Jacksons Gap 36861 2962 64-C-0113 Case, Anne Limestone Zoological Park 30191 Nick Davis Rd. Harvest 35749 3027 64-C-0008 City Of Gadsden Noccalula Falls Park Po Box 267 Gadsden 35902 3334 64-C-0138 Eastman, George Sequoyah Caverns 1306 County Rd 731 Valley Head 35989 9637 64-C-0146 Hardiman, Charles & Donna C & D Petting Zoo 24671 Elkton Rd Elkmont 35620 10140 64-C-0137 Higginbotham, Joseph & Charlotte Kids Country Farm 15746 Beasley Rd Foley 36535 1932 64-C-0125 Hightower, John 15161 Ward Rd West Wilmer 36587 3841 64-C-0139 Holmes Taxidermy Studio 1723 Rifle Range Rd Wetumpka 36093 7202 64-C-0132 Hornsby, Clyde Clyde's Tiger Exhibits And Refuge Rt. -

Confessions of a Conservationist Creating a Coup for In-Situ

Confessions of a Conservationist Creating a Coup for In-Situ Norman Gershenz SaveNature.Org, San Francisco, CA SAVENATURE.ORG SAVENATURE.ORG Circa 1988: Who knew from in-situ? Pieces of the Conservation Pie Partners Public Public participation education In-situ conservation Professional education Ex-situ Basic conservation research Advocacy SAVENATURE.ORG 500 species SSP programs in 2017 Diversity of Life On Earth 8.7 million (± 1.3 million) species SAVENATURE.ORG Changes in Wildlife Management Focus Traditional New Wildlife Management Focus on Individual Concern with all Species (Fishable, Huntable) Species Concern with Exotic Emphasis on native species species Species Oriented Habitat, community, landscape, ecosystem oriented SAVENATURE.ORG Who are the partners in the SaveNature.Org Consortium? • Zoos and Aquariums • Botanical Gardens, Science and Natural History Museums and Nature Centers •Educational Institutions: Schools and Universities • American Association of Zoo Keeper Chapters • Other National and International Conservation Organizations, NGO’s and Corporate Sponsors • General Public SAVENATURE.ORG SaveNature.Org Conservation Projects Sites: 11.6 million acres protected, $4.7 million raised Acres SAVENATURE.ORG Ecosystem services and function Discovering Diversity High value conservation Challenged SAVENATURE.ORG Meeting the Challenge SAVENATURE.ORG Área de Conservación Guancaste: A Latin American & global model SAVENATURE.ORG Área de Conservación Guancaste: A model for biodiversity conservation 1. Size- 1,260 km2 terrestrial, 430 km2 marine 2. Encompasses ecosystem diversity and ecological coherence: Marine island, coastal, freshwater, dry- forest, rainforest, cloud forest 3. Sea level to cloud forest elevation 4. Nuclei for peripheral expansion and restoration 5. Zoning for biodiversity conservation, and buffer zones 6. Research: discovering cryptic biodiversity through detailed molecular and inventory monitoring 7. -

Texas Parks and Wildlife Department Self-Evaluation Report

Texas Parks and Wildlife Department Self-Evaluation Report August 2007 TABLE OF CONTENTS I. Agency Contact Information............................................................................................................ 1 II. Key Functions and Performance...................................................................................................... 3 III. History and Major Events .............................................................................................................. 13 IV. Policymaking Structure.................................................................................................................. 19 V. Funding .......................................................................................................................................... 33 VI. Organization................................................................................................................................... 55 VII. Guide to Agency Programs............................................................................................................ 59 Executive Office............................................................................................................................ 61 Legal Division................................................................................................................................ 69 Administrative Resources Division ............................................................................................... 77 Communications Division............................................................................................................ -

Zoo in the United States Location Map Abilene

Zoo in the United States This GPS POI file is available here: https://poidirectory.com/poifiles/united_states/tourist_locations/Zoo-US.html Location Map Abilene Zoo Map African Safari Wildlife Park Map Akron Zoo Map Alabama Gulf Coast Zoo Map Alameda Park Zoo Map Alaska Zoo Map Alexandria Zoo Map Alligator Farm Zoological Pa Map Animal Discovery Zoological Map Animal Kingdom Zoo Map Animaland Zoological Park Map Arizona-Sonora Desert Museum Map Arkansas Alligator Farm and Map Audubon Zoo Map Austin Zoo Map Beardsley Zoo Map Bergen County Zoological Par Map Binder Park Zoo Map Birmingham Zoo Map Black Pine Animal Park Map Blank Park Zoo Map Bramble Park Zoo Map Brandywine Zoo Map BREC'S Baton Rouge Zoo Map Brevard Zoo Map Buffalo Zoo Map Buttonwood Park Zoo Map Caldwell Zoo Map Cameron Park Zoo Map Cape May County Park and Zoo Map Capron Park Zoo Map Cat Tales Zoological Park Map Catoctin Wildlife Preserve a Map Central Florida Zoo Map Central Park Zoo Map Chahinkapa Zoo Map Page 1 Location Map Charles Paddock Zoo Map Chattanooga Zoo Map Cherry Brook Zoo Map Cheyenne Mountain Zoo Map Children's Zoo at Celebratio Map Cincinnati Zoo Map Cindy Lou's Zoo Map Claws 'n Paws Wild Animal Pa Map Cleveland Zoo Map Clyde Peeling's Reptiland Map Cohanzick Zoo Map Columbian Park Zoo Map Columbus Zoo Map Como Zoo at Conservatory Map Cosley Zoo Map Cougar Mountain Zoo Map Coyote Point Museum Map Crossland Zoo Map Dakota Zoo Map Dallas Zoo Map David Traylor Zoo Map Detroit Zoo Map DeYoung Family Zoo Map Dickerson Park Zoo Map El Paso Zoo Map Ellen Trout -

Church/Rel Bldg

SUMMARY OF TEXAS PROJECT WILD ACTIVITIES SEPTEMBER 1, 2008 – AUGUST 30, 2009 WORKSHOP TYPE TOTAL TOTAL NUMBER OF EDUCATORS WORKSHOPS TRAINED PROJECT WILD 89 2372 PROJECT WILD AQUATIC 39 718 PW/AW COMBO 23 341 SCIENCE & CIVICS 8 292 SUB-TOTAL: 159 3723 FACILITATOR 5 122 OUTREACH 9 295 TOTAL: 173 4140 SUMMARY BY LOCATION SCHOOL OR ISD SITE: UNIVERSITY / COLLEGE: ALDINE ISD ABILENE CHRISTIAN UNIVERSITY COPELL ISD ANGELO STATE UNIVERSITY MARBLE FALLS ISD BAYLOR UNIVERSITY PFLUGERVILLE ISD NAVARRO COLLEGE SAN BENITO ISD SOUTWESTERN UNIVERSITY WILLIS ISD STEPHEN F AUSTIN UNIVERSITY REGION III ESC TARLETON STATE UNIVERSITY REGION VIII ESC TEXAS A & M UNIVERSITY AT COLLEGE STA ESC REGION XV TEXAS A & M UNIVERSITY AT CORPUS CHRISTI CENTINNEL HS TEXAS LUTHERAN UNIVERSITY COLLINS ACADEMY TEXAS STATE UNIVERSITY DOUGLASS ELEMENTARY THE UNIVSERSITY OF TEXAS AT AUSTIN ENV. STUDIES CENTER RISD (DALLAS) UNIVERSITY OF HOUSTON AT CLEAR LAKE FORT SETTLEMENT MIDDLE SCHOOL UNIVERSITY OF TEXAS AT SAN ANTONIO GINNINGS ELEMENTARY SCHOOL UT MARINE SCIENCE CTR HENDRICKSON HIGH SCHOOL (PFLUGERVILLE) VICTORIA COLLEGE L.A.C.E.Y. MIDDLE SCHOOL LEXINGTON ELEMENTARY SCOUT FACILITY OR YOUTH CAMPS: LUBBOCK EDUCATION CENTER CAMP ADVENTURE (WESTMINSTER) MARIAN MANOR ELEMENTARY SCHOOL CAMP ALLEN (NAVASOTA) THE OUTDOOR EDUCATION CENTER (TRINITY) ALL SAINTS CAMP – JOLT (POTTSBORO) OUTDOOR LEARNING CENTER (KATY) CAMP TONKAWA (COLLINSVILLE) THE OUTDOOR SCHOOL (MARBLE FALLS) LOST PINES BOY SCOUT CAMP (BASTROP) RASCO MIDDLE SCHOOL SAM HOUSTON AREA BOY SCOUT COUNCIL WALNUT BEND -

CIRCUS & RIDE ELEPHANT INCIDENTS March 26, 1950

CIRCUS & RIDE ELEPHANT INCIDENTS March 26, 1950: Dolly the circus elephant paid with her life for killing a 5-year-old boy. At the Sarasota, Florida winter quarters of Ringling Brothers, Barnum & Bailey Circus, Dolly snatched Edwin Rogers Schooley from the side of his horrified parents and crushed his head with one of her ponderous feet. Three days later Dolly was led into a pit. Despite protests from animal lovers all over the nation and from several zoos that wanted her, the 27-year-old elephant was given a huge dose of cyanide. According to newspaper reports, Dolly crumpled quickly in death and the pit was filled in over her huge body. Late 1980: A 1,500 pound baby elephant gored to death an animal handler who had prodded her with an axe handle. The 3-1/2-year-old African, a female named Charlie, pinned William David Sharp against the side of her plywood pen. The elephant gored Sharp at least twice in the abdomen with her four-inch tusks, puncturing his aorta. Sharp was pronounced death at the hospital. "The animal was being harassed and he was just protecting himself," said metro-Dade County homicide detective Woody Geisler. May 13, 1982: In Sallisaw, Oklahoma, five elephants bolted from the Carson and Barnes Circus while employees were preparing to move their equipment for another show. The elephants ran toward a coal pit and plunged off a 25-foot ledge. One of the male elephants was crushed to death. The four other elephants were eventually recaptured. May 25, 1983: In Atlantic City, New Jersey, an elephant, Frieda, owned by Clyde-Beatty Cole Brothers Circus seriously injured John Marshall of Mystic Islands.