The Role of Public Perceptions in Reducing Risks to Coastal Wildlife from Interactions with Dogs

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Environmental Status of the Near Shore Coastal Environment

Environmental Status of The Near Shore Coastal Environment April 2005 Environmental Status of The Near Shore Coastal Environment ISBN 1-877265-14-4 April 2005 Environmental Status of The Near Shore Coastal Environment i Executive Summary This report presents a comprehensive review of the environmental status of Otago’s near shore coastal environment. There is no current Otago Regional Council (ORC) coastal monitoring programme and therefore the ORC relies on resource consent monitoring to fulfil it’s responsibilities under the Resource Management Act (1991), the Regional Policy Statement and the Regional Plan: Coast. The only intensive coastal monitoring undertaken is in the vicinity of Dunedin and is due to the discharge of Green Island and Tahuna WWTP effluent, otherwise coastal monitoring of Otago’s coastal marine area (CMA) is limited both temporally and spatially. A review of coastal monitoring undertaken since the late 1990’s is presented with particular regard to water quality, the effects of discharges and possible effects on recreational and food gathering areas. Four main areas are covered: • Water quality monitoring undertaken as a requirement of resource consents. • Other monitoring as required by resource consents such as sediment monitoring programmes, ecological programmes, algal monitoring programmes or monitoring for the extent of mussel contamination. • ORC State of Environment monitoring of the major rivers that discharge into the Otago CMA. • A review of published research conducted in Otago’s CMA over the past 10 years. There is a need for a coordinated long term water quality and environmental monitoring programme for the whole of the Otago coastline, and the following monitoring and information gathering requirements are recommended: • That sufficient baseline information is collected to be able to establish water quality classes for the Otago CMA. -

Otago Peninsula Plants

Otago Peninsula Plants An annotated list of vascular plants growing in wild places Peter Johnson 2004 Published by Save The Otago Peninsula (STOP) Inc. P.O. Box 23 Portobello Dunedin, New Zealand ISBN 0-476-00473-X Contents Introduction...........................................................................................3 Maps......................................................................................................4 Study area and methods ........................................................................6 Plant identification................................................................................6 The Otago Peninsula environment........................................................7 Vegetation and habitats.........................................................................8 Analysis of the flora............................................................................10 Plant species not recently recorded.....................................................12 Abundance and rarity of the current flora...........................................13 Nationally threatened and uncommon plants......................................15 Weeds..................................................................................................17 List of plants .......................................................................................20 Ferns and fern allies ........................................................................21 Gymnosperms ..................................................................................27 -

Agenda of Otago Peninsula Community Board

Notice of Meeting: I hereby give notice that an ordinary meeting of the Otago Peninsula Community Board will be held on: Date: Thursday 18 February 2021 Time: 10:00 am Venue: Portobello Bowling Club, Sherwood Street, Portobello Sandy Graham Chief Executive Officer Otago Peninsula Community Board PUBLIC AGENDA MEMBERSHIP Chairperson Paul Pope Deputy Chairperson Hoani Langsbury Members Lox Kellas Graham McArthur Cheryl Neill Edna Stevenson Cr Andrew Whiley Senior Officer Chris Henderson, Group Manager Waste and Environmental Solutions Governance Support Officer Lauren McDonald Lauren McDonald Governance Support Officer Telephone: 03 477 4000 [email protected] www.dunedin.govt.nz Note: Reports and recommendations contained in this agenda are not to be considered as Council policy until adopted. OTAGO PENINSULA COMMUNITY BOARD 18 February 2021 Agenda Otago Peninsula Community Board - 18 February 2021 Page 2 of 40 OTAGO PENINSULA COMMUNITY BOARD 18 February 2021 ITEM TABLE OF CONTENTS PAGE 1 Opening 4 2 Public Forum 4 3 Apologies 4 4 Confirmation of Agenda 4 5 Declaration of Interest 5 6 Confirmation of Minutes 11 6.1 Otago Peninsula Community Board meeting - 12 November 2020 11 PART A REPORTS (Otago Peninsula Community Board has power to decide these matters) 7 Peninsula Connection Project 20 8 Governance Support Officer's Report 21 9 Funding Applications 32 10 Community Plan 2020-2021 36 11 Board Updates 37 12 Councillor's Update 38 13 Chairperson's Report 39 14 Items for Consideration by the Chairperson 40 Agenda Otago Peninsula Community Board - 18 February 2021 Page 3 of 40 OTAGO PENINSULA COMMUNITY BOARD 18 February 2021 1 OPENING Edna Stevenson will open the meeting with a reflection. -

Recreation in Dunedin Free and Under $5

Recreation in Dunedin Free and under $5 Contents Areas ................................................................................................................. 2 Map .................................................................................................................... 3 Foreword ......................................................................................................... 4 Life's a Beach ................................................................................................... 5 Sport and Exercise ......................................................................................... 7 Stadiums and Sports Centres .................................................................. 8 Volunteering .................................................................................................... 9 Finding out more .......................................................................................... 13 Eat Fresh and Grow Your Own ............................................................... 16 Dunedin Community Gardens .............................................................. 16 Where did you get that dress? ................................................................. 18 The Octagon Club ....................................................................................... 20 Central Dunedin .......................................................................................... 21 North ............................................................................................................. -

Otago Jan 2020

Birds New Zealand PO Box 834, Nelson 7040 www.osnz.org.nz Regional Representative: Mary Thompson 197 Balmacewen Rd, Dunedin 9010 [email protected] 03 4640787 Regional Recorder: Richard Schofield, 64 Frances Street, Balclutha 9230 [email protected] Otago Region Newsletter 1/2020 January 2020 Ornithological Snippets At Tomahawk Lagoon on 18th Jan, Andrew Austin counted at least 1248 Paradise Shelduck, though he estimates there could have been up to 1700 birds there. Warren Jowett reported a Long-tailed Cuckoo at Knox Church in Dunedin on 5th Jan A Chukar was seen from the Cardrona access road on 18th Jan, and a possible Crane sp was seen flying over the Matukituki valley between the Treble Cone turn- off and Cattle Flat on 31st Dec; a Pacific Golden Plover was seen & photographed at Papanui Inlet on 17th November. On the seabird front, 2 Pomarine Skua were reported th chasing gulls off Katiki Point on 16 Jan, and the Otago Daily Times reported hundreds of Red-billed & Pacific Golden Plover Black-backed Gulls, & White-fronted Terns, swarming while small fish washed ashore on 10th December at an Oamaru beach, which was described as a ‘‘spooky’’ scene http://tinyurl.com/vgxupkk A White Heron has been present at Hawkesbury Lagoon since at least 15th Dec, and another was near the Otakou Golf Course on 9th Jan, and 1 or 2 Little Black Shags were claimed from Andersons Bay Inlet and Tomahawk Lagoon on the latter date. Franny Cunninghame found a Little Owl by Highcliff Road on 29th Dec, just a couple of hundred metres from suburbia, while Tony Green came across a juvenile further up the road at Pukehiki on 20th; another reported on eBird near Balclutha on 28th Nov, was presumably “twitched” 4 days later by a couple of overseas birders. -

Minutes of Ordinary Council Meeting Held on 23 February 2021 3

Date: Tuesday 30 March 2021 Time: 10.00 am Venue: Council Chamber, Municipal Chambers, The Octagon, Dunedin Council OPEN ATTACHMENTS UNDER SEPARATE COVER ITEM TABLE OF CONTENTS PAGE 6.1 Ordinary Council meeting - 23 February 2021 A Minutes of Ordinary Council meeting held on 23 February 2021 3 6.2 Ordinary Council meeting - 9 March 2021 A Minutes of Ordinary Council meeting held on 9 March 2021 13 6.3 Extraordinary Council meeting - 17 March 2021 A Minutes of Extraordinary Council meeting held on 17 March 2021 20 7 Mosgiel-Taieri Community Board - 18 November 2020 A Minutes of Mosgiel-Taieri Community Board held on 18 November 2020 23 8 Otago Peninsula Community Board - 12 November 2020 A Minutes of Otago Peninsula Community Board held on 12 November 2020 30 9 Saddle Hill Community Board - 12 November 2020 A Minutes of Saddle Hill Community Board held on 12 November 2020 37 10 Saddle Hill Community Board - 18 February 2021 A Minutes of Saddle Hill Community Board held on 18 February 2021 43 11 Strath Taieri Community Board - 12 November 2020 A Minutes of Strath Taieri Community Board held on 12 November 2020 49 COUNCIL 30 MARCH 2021 12 Waikouaiti Coast Community Board - 18 November 2020 A Minutes of Waikouaiti Coast Community Board held on 18 November 2020 53 13 West Harbour Community Board - 18 November 2020 A Minutes of West Harbour Community Board held on 18 November 2020 60 14 West Harbour Community Board - 3 February 2021 A Minutes of West Harbour Community Board held on 3 February 2021 66 COUNCIL 30 MARCH 2021 Item 6.1 Item Council -

Coastal Dune Reserves Management Plan

Dunedin City Council Coastal Dune Reserves Management Plan July 2010 Contents Part One: Introduction and Background 1. Introduction ................................................................. 4 1.1 Scope of Coastal Dune Reserves Management Plan ................................... 4 1.2 Coastal Dune Reserves Included in this Management Plan ............................... 4 1.3 Interim Exclusion of Parts of Waikouaiti Domain ....................................... 4 1.4 Areas Not Included in this Management Plan ......................................... 5 2. Management Planning for Reserves ............................................. 6 2.1 Aims and Objective of Reserve Management Plans .................................... 6 2.2 Purpose of a Management Plan ................................................... 6 2.3 Existing Management Plans ...................................................... 6 2.4 Management Planning Under the Reserves Act 1977 ................................... 6 2.5 Consideration of Other Management Documents ...................................... 8 2.6 Review of Reserve Management Plans .............................................. 8 3 The Coastal Environment ...................................................... 9 3.1 The Importance of Coastal Dunes .................................................. 9 3.2 Sand Dunes and Natural Beach Dynamics ........................................... 9 3.3 Dune Vegetation .............................................................. 10 3.4 Coastal Wildlife .............................................................. -

Council Meeting Agenda 29 January 2020 - Agenda

Council Meeting Agenda 29 January 2020 - Agenda Council Meeting Agenda 29 January 2020 Meeting is held in the Council Chamber, Level 2, Philip Laing House 144 Rattray Street, Dunedin Members: Hon Marian Hobbs, Chairperson Cr Gary Kelliher Cr Michael Laws, Deputy Chairperson Cr Kevin Malcolm Cr Hilary Calvert Cr Andrew Noone Cr Michael Deaker Cr Gretchen Robertson Cr Alexa Forbes Cr Bryan Scott Cr Carmen Hope Cr Kate Wilson Senior Officer: Sarah Gardner, Chief Executive Meeting Support: Liz Spector, Committee Secretary 29 January 2020 02:00 PM Agenda Topic Page 1. APOLOGIES No apologies were received prior to publication of the agenda. 2. ATTENDANCE Staff present will be identified. 3. CONFIRMATION OF AGENDA Note: Any additions must be approved by resolution with an explanation as to why they cannot be delayed until a future meeting. 4. CONFLICT OF INTEREST Members are reminded of the need to stand aside from decision-making when a conflict arises between their role as an elected representative and any private or other external interest they might have. 5. PUBLIC FORUM Members of the public may request to speak to the Council. 6. PRESENTATIONS Catchment Group leaders Randall Aspinall, Geoff Crutchley, Lloyd McCall and Lyndon Strang will present information to the Councillors. 7. CONFIRMATION OF MINUTES 4 7.1 Minutes of the 11 December 2019 Council Meeting 4 7.2 Minutes of the 7 January 2020 Council Meeting 13 8. ACTIONS (Status of Council Resolutions) 16 9. CHAIRPERSON'S AND CHIEF EXECUTIVE'S REPORTS 18 1 Council Meeting Agenda 29 January 2020 - Agenda 9.1 Chairperson's Report 18 9.2 Chief Executive's Report 20 10. -

Implementation Committee Agenda - 10 March 2021 - Agenda

Implementation Committee Agenda - 10 March 2021 - Agenda Implementation Committee Agenda - 10 March 2021 Meeting is held in the Council Chamber, Level 2, Philip Laing House 144 Rattray Street, Dunedin Members: Cr Bryan Scott, Co-Chair Cr Gary Kelliher Cr Carmen Hope, Co-Chair Cr Michael Laws Cr Hilary Calvert Cr Kevin Malcolm Cr Michael Deaker Cr Andrew Noone Cr Alexa Forbes Cr Gretchen Robertson Hon Cr Marian Hobbs Cr Kate Wilson Senior Officer: Sarah Gardner, Chief Executive Meeting Support: Liz Spector, Committee Secretary 10 March 2021 09:00 AM Agenda Topic Page 1. APOLOGIES No apologies were received prior to publication of the agenda. 2. PUBLIC FORUM No requests to address the Committee under Public Forum were received prior to publication of the agenda. 3. CONFIRMATION OF AGENDA Note: Any additions must be approved by resolution with an explanation as to why they cannot be delayed until a future meeting. 4. CONFLICT OF INTEREST Members are reminded of the need to stand aside from decision-making when a conflict arises between their role as an elected representative and any private or other external interest they might have. 5. CONFIRMATION OF MINUTES 3 Minutes of previous meetings of the Implementation Committee will be adopted as true and accurate record(s), with or without changes. 5.1 Minutes of the 14 October 2020 Implementation Committee meeting 3 6. OUTSTANDING ACTIONS FROM RESOLUTIONS OF THE COMMITTEE There are no outstanding actions for the Implementation Committee. 7. MATTERS FOR CONSIDERATION 7 1 Implementation Committee Agenda - 10 March 2021 - Agenda 7.1 INFRASTRUCTURE STRATEGY FOR LTP 2021-31 7 To seek Council approval of the draft 2021-2051 Flood Protection, Land Drainage and River Assets Infrastructure Strategy which will form part of the Draft 2021-31 Long Term Plan (LTP). -

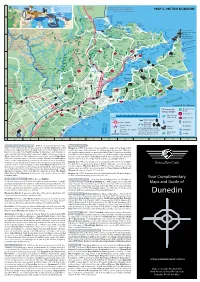

Dunedin Dunedin

Royal Some of the main Wood To Waikouaiti, To Karitane and Palmerston via scenic Pigeon Albatross Shag birdlife species Palmerston, Tern present in the Christchurch, route. Rejoins S.H. One at Waikouaiti MAP 2 - METRO DUNEDIN Dunedin region (approx 22 km from Warrington) Bellbird Yellow Eyed Little Blue Godwit Penguin Penguin 4.5 hrs Warrington Stilt Evansdale Waikouaiti Glen Tui Black or Pine Forest Careys Pied Oyster- White Variable Evansdale Mapoutahi Potato Point catcher Faced Pa site Oystercatcher River Rock Heron Ck Blueskin Purakaunui Climbing Fantail Banded Dotterel Black Swan Bay Doctors Point 30 min e Double Long ak h e ac Purakaunui Rd k Hill Rd a e e B Michies r u a a Heyward Point Taiaroa Head Rd Double h ik Crossing Mopanui Beach a Dam Osborne W Hill K Royal Albatross Centre Waitati Orokonui2 hrs NZ’s tallest Deep Stream Native Shortcut Rd Osborne The Painted Silverpeaks Semple tree Spit Fort Taiaroa Viaduct Forest 777m Bush Rd fortifications and Semple Rd Orokonui Beach Hindon 3 hrs 3 hrs 3 Rd Viaduct Mt Allen to Pulpit Rock d Blueskin Ecosanctuary Rd disappearing gun R oint Hightop Heyward P The most 4.5 - 5 hrs y Mihiwaka Stone e Pulpit Rock l Wetherston Green 560m The Mole Pilots Beach spectacular part of the 760m al Rd Fences V Hill guided penguin tours y Gorge is still ahead. ti a Aramoana a t w 640m i r The Organ Fortifications Penguin Beach 14 km to normal turn Christmas Ck a o Deborah Bay t Pipes Mt Cutten Harington Pt around point at Pukerangi.