This Opinion Is Not a Precedent of the TTAB 1724982 Alberta ULC V

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

FOOD, CLOTHING, SHELTER Food

COLORADO INDIANS – FOOD, CLOTHING, SHELTER Food What do these photos tell you about the food that these people ate? American Bison (Buffalo) This is a bison or American buffalo. Millions of bison once lived on the Great Plains of North America. In the 1800s, they were the largest animal native to North America. An average buffalo cow provided about 400 pounds of meat. That was enough meat to feed one person for at least 200 days. Buffalo Photo: Colorado Historical Society More About This Topic The bison lived on the blue grama and buffalo grass that grew on the plains. During the summer, when there was a lot of grass, the buffalo grazed in large herds. Some herds had several thousand animals. That was the best hunting season for the Plains Indians. The bison broke up into smaller herds during the winter, when there was less grass to eat. Their Own Words "From the top of Pawnee Rock, I could see from six to ten miles in almost every direction. The whole mass was covered with buffalo, looking at a distance like one compact mass....I have seen such sights a number of times, but never on so large a scale." Source: Colonel Richard Irving Dodge, May 1871, quoted in Donald Berthrong, The Southern Cheyenne (Norman, OK: University of Oklahoma Press, 1963, p. 31. Drying Buffalo Meat The pole in this photo holds strips of bison or buffalo meat that are drying in the sun. Removing the moisture kept the meat from spoiling. Dried meat could be kept for several months. -

A Study on the Characteristics of 20Th Century Womenfs Undergarments

IJCC, Vol. 6, No. 2, 83 〜92(2003) 15 A Study on the Characteristics of 20th Century Womenfs Undergarments Seo-Hee Lee and Hyeon-Ju Kim* Assistant Professor, Dept, of Fashion and Beauty, Konyang University Instructor, Dept, of Clothing Science, Seoul Women's University* (Received June 23, 2003) Abstract This study aims to classify -women's undergarments of the 20th century by periods, and to examine their characteristics. The research method consists of a literature study based on relevant documentary records and a demonstrative analysis of graphic data collected from each reference. The features of women's under garments obtained from the study are as fallows: First, silhouette changes of outer garments appear to influence the type and style of a new undergarment. Second, technological development results in a new type of undergarments. Third, the development of new material appears to influence functions and design of undergarments. Fourth, social changes including the development of sports affects the changes of undergarments. As seen so far, the form or type, material, and color in undergarment diversify when fashion changes become varied and rapid. As shown before the 20th century, the importance of undergarment's type, farm, and function gradually reduces according to the changes of -women's mind due to their social participation, although it still plays a role in correcting the shape of an outer garment based on the outer silhouette. The design also clearly shows the extremes of maximization and minimization of decoration. Key words : undergarment, modern fashion, lingerie, infra apparel the beginning of the 20th century, corsets and I. -

Women's Functional Swimwear, 1860-1920 Maxine James Johns Iowa State University

Iowa State University Capstones, Theses and Retrospective Theses and Dissertations Dissertations 1997 Women's functional swimwear, 1860-1920 Maxine James Johns Iowa State University Follow this and additional works at: https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/rtd Part of the Art and Design Commons, Home Economics Commons, Leisure Studies Commons, United States History Commons, Women's History Commons, and the Women's Studies Commons Recommended Citation Johns, Maxine James, "Women's functional swimwear, 1860-1920 " (1997). Retrospective Theses and Dissertations. 11468. https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/rtd/11468 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Iowa State University Capstones, Theses and Dissertations at Iowa State University Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Retrospective Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Iowa State University Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has been reproduced from the microfihn master. UMI fihns the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in Qrpewriter fiice, \«^e others may be from any type of computer primer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these Avill be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., m^s, drawings, charts) are reproduced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand comer and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. -

Protecting Fashion Designs: Not Only "What?" but "Who?" Julie Zerbo [email protected]

American University Business Law Review Volume 6 | Issue 3 Article 2 2017 Protecting Fashion Designs: Not Only "What?" but "Who?" Julie Zerbo [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.wcl.american.edu/aublr Part of the Intellectual Property Law Commons Recommended Citation Zerbo, Julie "Protecting Fashion Designs: Not Only "What?" but "Who?"," American University Business Law Review, Vol. 6, No. 3 (). Available at: http://digitalcommons.wcl.american.edu/aublr/vol6/iss3/2 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Washington College of Law Journals & Law Reviews at Digital Commons @ American University Washington College of Law. It has been accepted for inclusion in American University Business Law Review by an authorized editor of Digital Commons @ American University Washington College of Law. For more information, please contact [email protected]. PROTECTING FASHION DESIGNS: NOT ONLY “WHAT?” BUT “WHO?” JULIE ZERBO* “Design piracy can wipe out young careers in a single season. The most severe damage from lack of protection falls upon emerging designers, who every day lose orders, and potentially their businesses, because copyists exploit the loophole in American law.”1 – Lazaro Hernandez, Fashion Designer & Co–Founder, Proenza Schouler Introduction ...............................................................................................596 II. Fashion and the Impact of Design Piracy ............................................598 A. Loss of Sales and Business Opportunities -

The Platform Shoe History and Post WWII

The Platform Shoe – History and Post WWII By Martha Rucker Cave drawings from more than 15,000 years ago show humans with animal skins or furs wrapped around their feet. Shoes, in some form or another, have been around for a very long time. The evolution of foot coverings, from the sandal to present-day athletic shoe continues. Platform shoes (also known as Disco Boots) are shoes, boots, or sandals with thick soles at least four inches in height, often made of cork, plastic, rubber, or wood. Wooden-soled platform shoes are technically also known as clogs. They have been worn in various cultures since ancient times for fashion or for added height After their use in Ancient Greece for raising the height of important characters in the Greek theatre and their similar use by high-born prostitutes or courtesans in Venice in the 16th Century, platform shoes are thought to have been worn in Europe in the 18th century to avoid the muck of urban streets. Of the same practical origins are the Japanese geta, a form of traditional Japanese footwear that resembles both clogs and flip-flops There may also be a connection to the buskins of Ancient Rome, which frequently had very thick soles to give added height to the wearer. During the Qing Dynasty, aristocrat Manchu women wore a form of platform shoe similar to 16th century Venetian chopine, a type of women's platform shoe that was popular in the 15th, 16th and 17th centuries which were used to protect the shoes and dress from mud and street soil. -

2021 Leaders' Guide

Leaders’ Guide Edited 3/19/2021 Gooood Morning Campers! Camp Buffalo is glad to be back in action. We are offering the high-quality programing you have come to expect from Camp Buffalo with some new twists and a focus on Scout-Led customization of the summer camp experience. Camp Buffalo has an outstanding Shooting Sports Complex, and we staff the ranges with at least two instructors and super-sized time blocks where sensible to ensure excellent instruction. For Aquatics we take advantage of our pool, Liberty Lake, and the Tippecanoe River to offer many options. You will find lots of new elements this year, but the biggest change is Troop Choice. Each day Troops (or Patrols) will get to chose from a list of Troop Choice Activities to make their summer camp experience that they want it to be. Sorry, there are no Zoom or Virtual options in Troop Choice. COVID, yeah, I had to bring it up some time. Sagamore Council has run several large events with no significant issues. We plan to stay the course and keep things safe and keep things fun. Rules will be finalized closer to camp as the health department continues to update their guidance, but safety will be our focus. We anticipate robust safety measures and will require Scouts, Leaders, and Staff to follow them. In general, if you are looking for a camp with masks “recommended” , “preferred”, or “not at all”, Camp Buffalo is not the camp for you this year. In case you have not heard, our friend Billy Rood got his dream job at another BSA camp. -

Business Directory of Western New York

Central Library of Rochester and Monroe County · Miscellaneous Directories irriage Roorils, Best Paddocks, Best Stalls. (37 Large Box and 53 Lajge Single Stalls), Best Care and 'the Best Ventilated Stall.-, in Buffalo. J. L. DONOVAN, PROPR. GEORGE HERINCTON, JR SUPT. TEL. BRYANT 28C.. ITS WEST VJTIC3 STREET. NEW RICHELIEU HOTEL Swan Street, between Washington arj Ellicott. BUFFALO. N. Y. Refitted Throughout SteaStearrm Heat in Every Room NEW MSEMENT Baths RATES: $2.00 per Day. •!. PEcl. L WEEKLY RATES. 20th Century Methods A.^*.Tailorinc » Wholesale Prices. t i wi|$15 I X X A No More .* No Less. A' A; A: SUIT O'i OVER JOAT. SCOTCH ANO ENGLISH WOOLENS ONLY. IROQUOIS 'HOTEL BLOCK. rain with 363 MAIN .T. BUFFALO, N. Y. HENRI V. DER-fT, Practical Ratter. AH Kinds of SILK, STIFF and SOFT HATS Remodeled into Latest Styles. Silk and Stiff Hats Made to Order. X Cor. Main and Mohawk Sts. BUFFALO. H. Y. Central Library of Rochester and Monroe County · Miscellaneous Directories V Rochester Public Library _ Reference Book _ ^11~ \A Not For Circulation ^1 f CORRESPONDENCE W OFFICE 325 MAIN ST., CONFIDENTIAL » BUFFALO, N. Y. AUGUST JOHNSON, -»® IVTerchant Tailor EXCLUSIVELY \^) FINE TAILORING. „.„„. TII,C 1NI J, A A NOVELTIES IN " " ~ IMPORTED WOOLENS. 12 WEST EAGLE ST., BUFFALO, N. Y. INDIVIDUAL INSTRUCTION. 1 TUB stioriiJuiTTeGiinic Mitel M. JEANETTE BALLANTYNE, Principal. Law Stenographer. All Orders Carelully, Neatly and Promptly Filled. Reporting, Dictation, Typewriting, 129 Powers' Building, Making Up Cases, etc. n? powers, Rochester, N. Y. Competent Lady Assistants. Bldg. Typewriting Room. Notary with Seal. CALL AND SEE. WORK THAT RECOMMENDS ITSELF. -

Your Partner for Cleaning and Maintenance Products™

Buffalo Industries LLC – Your partner for cleaning and maintenance products™ Proudly Serving the Paint, Industrial, MRO & Marine Industries Since 1929 www.BuffaloIndustries.com Company Profile Buffalo has been “green” since long before the term was coined. Recycling and sustainability are the base upon which our business was founded. Since 1929 we’ve been producing quality recycled and new cloth rags for the Paint, Industrial, MRO and Marine markets. Our company helps to keep millions of pounds of textiles out of the waste stream every year. Locations & LTL Transit Times At Buffalo, we continue to make investments in our future to ensure that our product offerings, customer service, sales staff and warehousing are cutting edge. We have manufacturing and distribution centers near Seattle and in Houston, uniquely positioning us to service the entire country quickly and cost-effectively. Thank you for browsing our catalog and for your continued business. You can find more information on our website at BuffaloIndustries.com, including product details and images available for download. For further assistance, please contact customer service: 800-683-0052. Now, more than ever, we truly are “your partner for cleaning and maintenance products.” TOLL-FREE: 800-683-0052 Product Categories Rags & Wipers: White Cloth Pages 2-3 Colored Cloth Pages 4-5 Cloths & Towels: Bar Towels & Huck Towels Page 6 Terry Towels & White Half Towels Page 7 Microfiber Cleaning Cloths Page 8 Diaper Cloths, Flannel Dust Cloths & Glass Towels Page 9 Shop Towels & Painter’s -

ONGUARD's Economy Boot

ONGUARD Industries, L.L.C… Known Worldwide for Safety and Protection ONGUARD Industries, L.L.C. prides itself for remaining ahead of the competition when it comes to safety. Listed below are certifications attained by ONGUARD: NFPA 1991, 2005 Edition (National Fire Protection Association): To pass the applicable boot requirements for NFPA 1991, 2005 edition, boots are independently tested to verify compliance. Boots must resist permeation for 1 hour or more against each chemical in the NFPA 1991, 2005 edition battery. The battery consists of 15 chemical liquids and 6 chemical gases. The boots must also pass a flammability resistance test. ASTM F2413-05: For more than sixty years, the predecessor to this specification, ANSI Z41, established the performance criteria for a wide range of footwear to protect from hazards that affect the personal safety of workers.The specification contains performance requirements for footwear to protect work- ers’ feet from the following hazards by providing: (1) impact resistance for the toe area of footwear; (2) compression resistance for the toe area of the footwear; (3) metatarsal impact protection that reduces the chance of injury to the metatarsal bones at the top of the foot; (4) conductive properties which reduce hazards that may result from static electricity buildup; and reduce the possibility or ignition of explosives and volatile chemicals; (5) electric shock resistance, to protect the wearer when accidental contact is made with live electric wires; (6) static dissipative (SD) properties to reduce hazards due to excessively low footwear resistance that may exist where SD footwear is required; (7) puncture resis- tance of footwear bottoms; (8) chain saw cut resistance; and (9) dielectric insulation. -

Footwear for Women: Nina Footwear Co

UNITED STATES TARIFF COMMISSION FOOTWEAR FOR WOMEN: NINA FOOTWEAR CO. , INC. LONG ISLAND CITY, N. Y. Report to the President on Investigation No. TEA-F-58 Under Section 301(c)(l) of the Trade Expansion Act of 1962 TC Publication 656 Washington, D. C. March 1974 UNITED STATES TARIFF COMMISSION COMMISSIONERS Catherine Bedell, Chairman Joseph 0. Parker, Vice Chairman Will E. Leonard, Jr. George M. Moore J. Banks Young Italo H. Ablondi Kenneth R. Mason, Secretary to the Commission Address all communications to United States Tariff Commission Washington, D. C. 20436 C 0 N T E N T S Report to the President--------------------------------------- 1 Finding of the Commission--------------------------------- 2 Views of Vice Chairman Parker and Conunissioner Ablondi---- 3 Views of Commissioners Leonard and Young------------------ 5 Dissenting views of Commissioner Moore--------------------- 6 Information obtained in the investigation: Description of articles under investigation--------------- A-l U. S. tariff treatment: Applicable TSUS items---------------------------------- A-6 Rates of duty---------------------~-------------------- A-7 U. S. consumption, production, and imports------------------ A-9 Prices----------------------------------------------------- A-13. U.S. and foreign wage rates-------~----------------------- A-15 Data relating to Nina Footwear Co., Inc.: Corporate history, plant, and equipment--------------- A-17 Product and prices------------------------------------ A-18 Sales and distribution-------------------------------~- -

Shop Buffalo Niagara

buffalo Shop niagara @herstorybuffalo KATIE AMBROSE Just imagine a weekend full of stylish shopping, delicious food and cocktails, limitless entertainment and a relaxing treatment at the spa - all with a couple of your closest girlfriends. It’s the perfect getaway. Browse through the top fashions of over 200 designer outlets in Niagara Falls USA or discover the latest trends in Buffalo’s new boutiques. To make your trip completely care-free, we’re showcasing the finest shops, malls and neighborhoods along with an itinerary for a fabulous girlfriend getaway. Welcome to the nearest faraway place! VisitBuffaloNiagara.com/girlfriend whitelinenteahouse RHEA ANNA WHAT’S INSIDE GIRLFRIEND GETAWAYS ................ 2-5 ALLENTOWN ...................................30-33 ELMWOOD VILLAGE ........................6-9 MALLS .................................................34-38 HERTEL AVENUE ............................10-13 MENSWEAR ............................................39 DOWNTOWN .................................... 14-17 MUSEUM GIFT SHOPS ...............40-41 LEWISTON .......................................... 18-21 HIDDEN GEMS .............................. 42-43 EAST AURORA ............................... 22-25 BORDER CROSSING INFO ............ 44 WILLIAMSVILLE ..............................26-29 ON THE COVER Photography by City Lights Studio / Models: Myari Ware and Corrinne Wheatley Custom made dresses by Made by Anatomy and Dana Saylor / Hair by Kristin Draudt, Fawn & Fox Salon Makeup by Christina Sergakis, Koukla Cosmetics / Accessories -

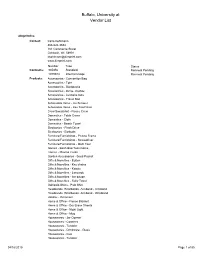

UB Licensed Vendor List.Pdf

Buffalo, University at Vendor List 4imprint Inc. Contact: Karla Kohlmann 866-624-3694 101 Commerce Street Oshkosh, WI 54901 [email protected] www.4imprint.com Number Type Status Contracts: 965356 Standard Renewal Pending 1079374 Internal Usage Renewal Pending Products: Accessories - Convention Bag Accessories - Tote Accessories - Backpacks Accessories - purse, change Accessories - Luggage tags Accessories - Travel Bag Automobile Items - Ice Scraper Automobile Items - Key Tag/Chain Crew Sweatshirt - Fleece Crew Domestics - Table Cover Domestics - Cloth Domestics - Beach Towel Electronics - Flash Drive Electronics - Earbuds Furniture/Furnishings - Picture Frame Furniture/Furnishings - Screwdriver Furniture/Furnishings - Multi Tool Games - Bean Bag Toss Game Games - Playing Cards Garden Accessories - Seed Packet Gifts & Novelties - Button Gifts & Novelties - Key chains Gifts & Novelties - Koozie Gifts & Novelties - Lanyards Gifts & Novelties - tire gauge Gifts & Novelties - Rally Towel Golf/polo Shirts - Polo Shirt Headbands, Wristbands, Armband - Armband Headbands, Wristbands, Armband - Wristband Holiday - Ornament Home & Office - Fleece Blanket Home & Office - Dry Erase Sheets Home & Office - Night Light Home & Office - Mug Housewares - Jar Opener Housewares - Coasters Housewares - Tumbler Housewares - Drinkware - Glass Housewares - Cup Housewares - Tumbler 04/16/2019 Page 1 of 85 Jackets / Coats - Jacket Jackets / Coats - Coats - Winter Jewelry - Lapel Pin Jewelry - Spirit Bracelet Jewelry - Watches Miscellaneous - Umbrella Miscellaneous