48 Laurens Street 2017

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Port Orange Ponce Inlet Fishing Inside South Daytona Daytona Beach Shores with Dan

PORT ORANGE PONCE INLET FISHING INSIDE SOUTH DAYTONA DAYTONA BEACH SHORES WITH DAN Indian River reeks while shrimp run in Halifax River Page B7 Vol. 8, No. 24 Your Local News and Information Source • www.HometownNewsOL.com Friday, July 5, 2013 $ OFF ANY Community VCOG structure could change 19 REPAIR Must be presented atAdvanced time of repair cannotAir 767-1654 be combined w/any other offer. Notes By Erika Webb all Volusia County residents. Port Orange [email protected] “Today’s staff, in our cities and county, has Same Day great rapport with their professional counter- Emergency Service Centennial events Volusia Council of Governments will remain parts in other governments,” Ms. Swiderski its own entity. wrote. “The need to develop consensus is not for July At a workshop June 24, focused on the results as necessary as it once was.” State Lic#CAC1817470 of a 360 survey of the organization, city and “In essence we have worked our way out of The city continues its county officials voted unanimously to continue a job,” she added. Lasts and Lasts and Lasts yearlong Centennial cele- as VCOG rather than assemble under the Volu- A total of 39 elected officials and 15 man- SM Port Orange bration with events and sia League of Cities. agers from 14 jurisdictions, including 12 386-767-1654 activities planned during The survey, completed by city managers and cities, Volusia County and the Volusia WE FIX AIR CONDITIONERSwww.AdvancedAirOnline.com 775605 July. From a free movie to a elected officials, was designed as a complete County School Board, returned the survey. -

Food and Drinks Menu

‘Hamu’ in kiswahili means ‘appetite’ and ‘desire’ Our mission is to welcome our guests in a friendly and warm environment where they can enjoy some good time with their friends, their family or to socialize with new people. Hamu is not just an ordinary restaurant; our priority is to offer you an experience. The menu is conceptualized in the same way as a “Drinking Bistro”. We combine our Italian traditions with the freshness of the Tanzanian ocean food, fresh vegetables and local fruit. Our menu is light, fresh and entirely homemade. Our bar is specialized in making amazing cocktails on par with international standards. Our spirits selection and wine list are always evolving; aspiring to the highest standard. Thanks to our experience, we can satisfy the majority of customer requests and adapt according to your taste. We are able to cater for special requests (Vegetarian, Halal, Non-Alchoholic or gluten free). For more info or bookings: SKY Mall, Haile Selassie Rd, Masaki, Dar es Salaam. T. +255 746 800 000 Food Menu Sta rters Bruschetta Six slices of crispy bread with garlic, fresh tomato and basil 12,000 Baba Ganoush Roasted aubergines with yogurt and mint 12,000 Spanish Tortilla Tortilla with eggs and spicy potato 12,000 Quiche Zucchini salty cake (eggs and puff pastry) 12,000 Pappa al Pomodoro Italian typical tomato soup melted with bread, egg plants and olive oil 15,000 Prawns Saganaki Sauteed prawns with tomato basil sauce 18,000 Fresh and Quick (RECOMMENDED FOR Lunch) Beef Carpaccio With vegetables beurre noisette and fennel 21,000 -

Cold Drinks Raw Juices Fruit Shakes Slush Puppy

non-alcoholic beverages COLD DRINKS SMOOTHIE BAR WATER ................................18 ....... 35 PINEAPPLE EXPRESS ............... 42 still / sparkling pineapple ~ banana ~ coconut milk APPLETISER/RED GRAPETISER ......28 SUMMER BREEZE ...................... 42 ICE TEA ............................................ 26 strawberry ~ banana ~ almond milk ROADHOUSE peach / lemon PEANUT BUTTER DELIGHT ........ 42 SHAKES SODA CAN 300 ML ......................... 22 peanut butter ~ yoghurt CHOCOLATE/MILO/BANANA coke / coke zero / fanta orange / fanta banana ~ cinnamon grape / fanta pineapple / stoney / BUBBLEGUM/LIME/COFFEE sprite / sprite zero / creme soda BERRY BLAZE ................................ 42 VANILLA / STRAWBERRY MIXER CAN 200 ML ....................... 16 blueberry ~ strawberry ~ yoghurt ~ honey STANDARD .......................32 ....... 38 HOT DRINKS club soda / lemonade / bitter lemon / DBL THICK .........................36 ....... 42 gingerale / indian tonic / pink tonic / ESPRESSO ..........................16 ....... 22 blue tonic RAW JUICES BAR ONE / PEANUT BUTTER FRESHLY SQUEEZED AMERICANO .....................20 ...... 26 KIDDIES JUICE BOXES ............... 15 PEPPERMINT CRISP CARROT~ORANGE~GINGER ...............36 CAPPUCCINO ....................24 ....... 32 RED BULL ....................................... 36 BEETROOT~APPLE~STRAWBERRY ...36 STANDARD .......................36 ....... 42 RED CAPPUCCINO ...........26 ...... 36 DBL THICK .........................40 ...... 46 FRUIT JUICE .......................28 ..... 32 KALE~CELERY~APPLE -

Chapter 11 CORINTHIAN COLLEGES, INC., Et Al. Case

Case 15-10952-KJC Doc 712 Filed 08/05/15 Page 1 of 2014 IN THE UNITED STATES BANKRUPTCY COURT FOR THE DISTRICT OF DELAWARE In re: Chapter 11 CORINTHIAN COLLEGES, INC., et al.1 Case No. 15-10952-CSS Debtor. AFFIDAVIT OF SERVICE STATE OF CALIFORNIA } } ss.: COUNTY OF LOS ANGELES } SCOTT M. EWING, being duly sworn, deposes and says: 1. I am employed by Rust Consulting/Omni Bankruptcy, located at 5955 DeSoto Avenue, Suite 100, Woodland Hills, CA 91367. I am over the age of eighteen years and am not a party to the above-captioned action. 2. On July 30, 2015, I caused to be served the: a) Notice of (I) Deadline for Casting Votes to Accept or Reject the Debtors’ Plan of Liquidation, (II) The Hearing to Consider Confirmation of the Combined Plan and Disclosure Statement and (III) Certain Related Matters, (the “Confirmation Hearing Notice”), b) Debtors’ Second Amended and Modified Combined Disclosure Statement and Chapter 11 Plan of Liquidation, (the “Combined Disclosure Statement/Plan”), c) Class 1 Ballot for Accepting or Rejecting Debtors’ Chapter 11 Plan of Liquidation, (the “Class 1 Ballot”), d) Class 4 Ballot for Accepting or Rejecting Debtors’ Chapter 11 Plan of Liquidation, (the “Class 4 Ballot”), e) Class 5 Ballot for Accepting or Rejecting Debtors’ Chapter 11 Plan of Liquidation, (the “Class 5 Ballot”), f) Class 4 Letter from Brown Rudnick LLP, (the “Class 4 Letter”), ____________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________ 1 The Debtors in these cases, along with the last four digits of each Debtor’s federal tax identification number, are: Corinthian Colleges, Inc. -

View It Online Here

19 Monongahela River Mapping Marion County s Downtown Fairmont R ' Hamilton Round Barn Follow Route 250 Top Attractions toward Mannington c L E C 7979 Table GH 250 J K I B FairmontFairmont of Contents H J 19 I GF A 4 Outdoor Recreation 6 Local Flavor White Hall C 8 A Treasured Past 250 Pleasant Valley 10 Create & Rejuvenate 310 12 Italy in Appalachia 14 Civil War 16 Family Fun M o 18 Heritage non gahela River 21 Relax and Unwind 79 D 22 Entertainment 24 Play 27 Golfing 250 Places to go 27 Craft Beverages 28 Places to Shop A VISITOR CENTER / KOREAN F COUNTRY CLUB BAKERY K MARION COUNTY HISTORICAL {31 Travel Resources WAR MEMORIAL FLAG Taste the original pepperoni roll. SOCIETY MUSEUM Your gateway to Marion County! Share Marion County’s deep roots and step 32 Places to Eat G BARRACKVILLE B DOWNTOWN FAIRMONT COVERED BRIDGE into the old jail cells. 36 Places to Stay Discover historic architecture, quaint shops, Stroll the rustic, old-timey bridge, tucked HAMILTON ROUND BARN IN and small-town charm. in a scenic setting. MANNINGTON (not pictured) CONVENTION & VISITORS BUREAU OF 38 Places to Gather Browse the history of agriculture through C PRICKETTS FORT STATE PARK H FRANK & JANE GABOR MARION COUNTY Meet 18th century reenactors and learn WV FOLKLIFE CENTER farming tools. Leisha Elliott - Executive Director about heritage crafting. Explore our Appalachian heritage PHOTO CREDITS: Ben Amend, D VALLEY FALLS STATE PARK and history. Marion County CVB, Molly Wolff. Watch the pounding falls, go fishing, or I SAGEBRUSH ROUND-UP The information contained in this Visitors explore the mountains. -

Owner Info with Codes.Pdf

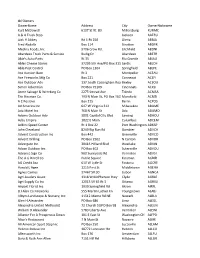

tbl Owners OwnerName Address City OwnerNickname Kurt McDowell 6107 St Rt. 83 Millersburg KURMC A & A Truck Stop Jackson AATRU Jack H Abbey Rd 1 Rt 250 Olena ABBJA Fred Abdalla Box 114 Stratton ABDFR Medina Foods, Inc 9706 Crow Rd. Litchfield ABDNI Aberdeen Truck Parts & Service Budig Dr Aberdeen ABETR Abie's Auto Parts Rt 35 Rio Grande ABIAU Ables Cheese Stores 37295 5th Ave/PO Box 311 Sardis ABLCH Able Pest Control PO Box 1304 Springfield ABLPE Ace Auction Barn Rt 3 Montpelier ACEAU Ace Fireworks Mfg Co Box 221 Conneaut ACEFI Ace Outdoor Adv 137 South Cassingham RoadBexley ACEOU Simon Ackerman PO Box 75109 Cincinnati ACKSI Acme Salvage & Wrecking Co 2275 Smead Ave Toledo ACMSA The Bissman Co. 193 N Main St, PO Box 1628Mansfield ACMSI A C Positive Box 125 Berlin ACPOS Ad America Inc 647 W Virginia 312 Milwaukee ADAME Ada Motel Inc 768 N Main St Ada ADAMO Adams Outdoor Adv 3801 Capital City Blvd Lansing ADAOU Adco Empire 1822 E Main Columbus ADCEM Adkins Speed Center Rt 1 Box 22 Port Washington ADKSP John Cleveland 8249 Big Run Rd Gambier ADVCH Advent Construction Inc Box 442 Greenville ADVCO Advent Drilling PO Box 2562 N Canton ADVDR Advergate Inc 30415 Hilliard Blvd Westlake ADVIN Advan Outdoor Inc PO Box 402 Sutersville ADVOU Advance Sign Co 900 Sunnyside Rd Vermilion ADVSI The A G Birrell Co Public Square Kinsman AGBIR AG Credit Aca 610 W Lytle St Fostoria AGCRE Harold L Agee 1215 First St Middletown AGEHA Agnes Carnes 37467 SR 30 Lisbon AGNCA Agri-Leaders Assoc 1318 W McPherson Hwy Clyde AGRLE Agri Supply Co Inc 12015 SR 65 Rt 3 Ottawa -

CLASP Starts for Lubbocl~ * * * 13 Schools Fountain in Drive CLASP

CLASP Starts for Lubbocl~ * * * 13 Schools Fountain In Drive CLASP. a coined word, like Plan Set ned to the clasp of a hand, the clasp of an idea as well as a A water fountain with seven clasp bmding together, 1s be columns of water shooting 30 coming a symbol of thousands of form<'r college and uni\'er ~~~io:.i~~n=~~n;P~~7gwi:~;~o~ FEBRUARY, 1964 VOL XV, NO. 1 sity students in Texas. mark the Broadway and College _____:...._ _____________________ The imtials stand for College entrance to Texa~ Tech ir plans H.ooolciMopl.-. Loyalty Alumni Support Pro instituted by the Tech Saddle Fo.tW...... Sh•lolo9'•"' gram Tramps, men·s spirit organiza· CLASP is a cooperati\e ef lion carry through fort by the alumni of college~ Cost of the project, approxi and universities private, de mately $60,000, will be met nominational and public jom through contributions by stud ing forces to strengthen higher ents, ex-students, Lubbock bul:>i education m Texas and the nessmen and fnends of the Col Southwe~t. and at the same lege,according to James Cole, t1me, to assist their re~pective Saddle Tramp member who is alma maters. co-chairman or the project, The heart of the program is serving with Paul Dinsmore. a simullaneous, coo1·d inated fund rlriw among 1he!oie ex The fund drive was kicked students off Sunday, Feb. 16 Cole said Texas Technological College An initial contribution or is a CLASP participant and will $2.500 toward the con.,truction be acti"·e in several cities before o r the fountain "a . -

Adult Shakes ��������������������������

Add A Scoop Of French Vanilla Ice Cream (190 cal) 2.5 SOUR CREAM CAKE DOUGHNUTS 999 cal 8 Sweetened Crème Fraîche, Blueberry Compote CHOCOLATE CHIP COOKIES 1044 cal 6.5 3 Freshly Baked Chocolate Chip Cookies TRIPLE CHOCOLATE COOKIES 1017 cal 6.5 3 Freshly Baked White & Milk Chocolate Chip Cookies COOKIE TRIO 900-1220 cal 6.5 Pick 3 Freshly Baked Cookies MEXICAN VANILLA 640 cal 7.5 CHOCOLATE CHIP COOKIE 980 cal 7.5 CHOCOLATE PEANUT BUTTER 1160 cal 7.5 STRAWBERRY CHEESECAKE 790 cal 7.5 SALTED CARAMEL 860 cal 7.5 BANANA SPLIT 758 cal 7.5 ADULT SHAKES � � � � � � � � � � � � � THE KING 743 cal 9 Blue Chair Bay Banana Rum, Peanut Butter, Bacon WHISKEY BANANA SPLIT 615 cal 9 Old Overholt Rye, Liber & Co Pineapple Gum Syrup, Monin Dark Chocolate, Roasted Banana & Strawberry Purees IRISH COFFEE 640 cal 9 Baileys Irish Cream, Alamo Cold Brew Coffee BEE’S KISS 550 cal 9 Flor D’Cana 7yr Rum, Honey, Honeycomb Cereal BRANDY ALEXANDER 550 cal 9 Courvoisier VS Cognac, BOLS Crème de Cacao, Monin Dark Chocolate THE GRASSHOPPER 720 cal 9 BOLS Crème de Menthe & Crème de Cacao CHOCOLATE COVERED CHERRY 627 cal 9 Cherry Heering, Monin Dark Chocolate BREAKFAST STOUT 825 cal 8 Founders Breakfast Stout, Maple, Bacon 2,000 calories in a day is used for general nutritional advice, but calorie needs vary Westlakes - Jan 2019 MOSCOW MULE 170 cal Tito’s Handmade Vodka, Top Hat Ginger Beer, Lime 10 RATED MARGARITA: FROZEN OR ON THE ROCKS 230 cal Exotico Tequila Blanco, G Naranja Orange Liqueur, Lime 10 GOLD RUSH 225 cal Elijah Craig Small Batch Bourbon, Barrow’s Intense -

The-Collective-Drinks-Menu.Pdf

DRINKS Alcoholic beverages BOTTLE TOT BOTTLE TOT Whisky - Bourbon Speyside Single Malt Jack Daniels Old No. 7 7500 400 Singleton of Dufftown 12000 600 Jack Daniels Honey 8000 500 Glenlivet Founders 14000 550 Reserve Bulleit Bourbon 8500 400 Glenlivet - 15YO 14000 600 Makers Mark 12000 600 Glenlivet - 18YO 18000 900 Wild Turkey - 8YO 7500 400 Glenfiddich - 12YO 14000 600 Knob Creek - 9YO 12000 600 Glenfiddich Solera Woodford 12000 600 18000 800 Reserve Irish Whisky Glenfiddich - 18YO 21000 1100 Jameson 5000 300 Highlands & Island Bushmills Original 7500 400 Single Malts Blended Scotch Whisky Glenmorangie Original 10000 500 Ballantines 5000 300 Talisker - 10YO 12000 600 Famous Grouse 5000 300 Clynelish - 14YO 15000 700 Johnnie Walker Red 5500 300 Jura 12000 600 Johnnie Walker Black 7500 400 Cognac/Brandy Chivas Regal - 12YO 8500 500 Viceroy 5000 300 Luxury Blended Scotch Hennessy VS 10000 500 Whisky Hennessy VSOP 17000 800 Monkey Shoulder 12000 600 Hennessy XO 62000 3000 Chivas Regal -18YO 17000 750 Martell VS 10000 500 Johnie Walker Double Martell VSOP 17000 800 13000 650 Black Remy Martin VSOP 22000 1100 Johnie Walker Green 12500 600 Remy Martin XO 62000 3000 Johnie Walker Gold 18000 800 Reserve Vodka Johnie Walker - 18YO 18000 800 Sky Vodka Blue 5000 250 Johnie Walker Blue Absolut Vodka Blue 5000 250 40000 2000 Label Absolut Vodka Pepper 5000 250 Johnie Walker King 140000 6000 Stolichnaya Vodka 5000 250 George V Ketel One 6000 300 Islay Single Malts Grey Goose Original 9500 500 Lagavulin 16YO 22000 950 Ciroc Vodka 13000 450 Lowland Single malts Glenkinchie 12000 600 BOTTLE TOT BOTTLE TOT Tequila/Shooters Gin Tequila Rose 6000 300 Beefeater Gin 5000 250 Olmeca Gold 6000 250 Gordon’s 5000 250 Jose Cuervo Silver 6000 300 Bombay Sapphire 6000 300 Jose Cuervo Gold 6000 300 Jaisalmer 10000 400 Jagermeister 6000 300 Tanqueray Dry 6000 300 Sambucca Molinari 8000 350 Tanqueray No. -

Beer Brand Listing 2019 (Pdf) Download

Run Date: 30-JUL-19 BRENTWOOD DISTRIBUTING CO. Page 001 Brand I.D. File Print Out Time: 14:19:40 ================================================================================ Brand Description Type Supp # 1 IC LIGHT MANGO B FUH 11 BITBURGER B 13 IC PUMPED MANGO B FUH 16 MISSION SHPWRKED DBL IPA B GAL 17 SIERRA SOUTH HEMIS B FUH 18 BROOKLYN SUMMER B FUH 19 DUCK RABBIT PORTER B WIL 20 SAM ADAMS SUMMER VARIETY B FUH 21 KARLOVACKO B VEC 22 DEL DUCATO TORREN B FUH 24 COLT BLAST RASP. MELON B GAL 25 BLUE POINT SUMMER B GAL 29 PENN SUMMER BERRY B FUH 30 PENNDEMONIUM B FUH 31 PEAK ORG. VARIETY B WIL 32 WITTEKERKE FRAMBOISE B SAV 33 ROGUE SOMER B FUH 34 ANGRY ORCH. ELDER B FUH 35 FULL PINT TRI IPA B WIL 37 TERRAPIN MONKS REVENGE B WIL 38 WEYERBACHER VARIETY B VEC 39 OTTER CREEK SAMPLER B VEC 40 BALLAST PT HI WEST VICT A B FES 41 BALLAST PT SCULPIN NITRO B FES 42 ITHACA STICKY B FES 43 ITHACA MISSING LINK B FES 44 AVERY MAHARAJA B FUH 45 AVERY RAJA B FUH 46 OMEGANG RARE VOS B FUH 48 BOULDER BLUE B FUH 49 F/D WOODY CREEK B FUH 50 BAVIK B SAV 51 EAST END HUELL PILS B VEC 52 EAST END BRETT HOP B VEC 53 IC GOLDEN LAGER B FUH 54 S/POINT W.HOG DIXIE PEACH B FES 55 SIERRA HELLE TROPIC B FUH 56 ANDERSON PEACHY BARLEY B VEC 57 BOULDER DATE OAK AGED B FUH 58 AVERY OUT OF BOUNDS B FUH 59 S/POINT NUDE BEACH B FES 61 GREAT DIVIDE TITAN IPA B GAL 62 HEBREW BITTER LENNY B SAV 63 WOLAVERS WILDFLOWER B VEC 64 ERIE VARIETY B VEC 65 SLY FOX ROYAL WEISSE B GAL 66 WEYERBACHER SLAM DUNKEL B VEC 67 WEYERBACHER SIMCOE DBL IP B VEC 68 ABITA RESTORATION B FUH 69 ABITA SOS B FUH 70 ANCHOR SUMMER B FUH 71 GOLD CROWN B SAV 72 VICTORY SUMMER LOVE B VEC 73 LANCASTER DBL CHOC B VEC 74 O.BLUES GUBNA B VEC 75 BUTTERNUT HEINIEWEISSE B VEC 76 ROCHEFORT 10 B FUH 77 STOUDTS TRIPLE B VEC 78 TROEGS JAVAHEAD B VEC 79 HEV.SEAS SMALL CRAFT B VEC 80 HEV.SEAS SUNKEN SAMPLER B VEC 81 BUTTERNUT VARIETY B SAV 82 BUTTERNUT MOO THUNDER B SAV 83 HEBREW MESSIAH BOLD B SAV 84 PETRUS BLONDE B SAV 85 UNIBROUE 25TH ANNIV. -

Appendix Unilever Brands

The Diffusion and Distribution of New Consumer Packaged Foods in Emerging Markets and what it Means for Globalized versus Regional Customized Products - http://globalfoodforums.com/new-food-products-emerging- markets/ - Composed May 2005 APPENDIX I: SELECTED FOOD BRANDS (and Sub-brands) Sample of Unilever Food Brands Source: http://www.unilever.com/brands/food/ Retrieved 2/7/05 Global Food Brand Families Becel, Flora Hellmann's, Amora, Calvé, Wish-Bone Lipton Bertolli Iglo, Birds Eye, Findus Slim-Fast Blue Band, Rama, Country Crock, Doriana Knorr Unilever Foodsolutions Heart Sample of Nestles Food Brands http://www.nestle.com/Our_Brands/Our+Brands.htm and http://www.nestle.co.uk/about/brands/ - Retrieved 2/7/05 Baby Foods: Alete, Beba, Nestle Dairy Products: Nido, Nespray, La Lechera and Carnation, Gloria, Coffee-Mate, Carnation Evaporated Milk, Tip Top, Simply Double, Fussells Breakfast Cereals: Nesquik Cereal, Clusters, Fruitful, Golden Nuggets, Shreddies, Golden Grahams, Cinnamon Grahams, Frosted Shreddies, Fitnesse and Fruit, Shredded Wheat, Cheerios, Force Flake, Cookie Crisp, Fitnesse Notes: Some brands in a joint venture – Cereal Worldwide Partnership, with General Mills Ice Cream: Maxibon, Extreme Chocolate & Confectionery: Crunch, Smarties, KitKat, Caramac, Yorkie, Golden Cup, Rolo, Aero, Walnut Whip, Drifter, Smarties, Milkybar, Toffee Crisp, Willy Wonka's Xploder, Crunch, Maverick, Lion Bar, Munchies Prepared Foods, Soups: Maggi, Buitoni, Stouffer's, Build Up Nutrition Beverages: Nesquik, Milo, Nescau, Nestea, Nescafé, Nestlé's -

Aiii Ting Wori H 11845 Skyline Blvd., Los Gatos, Ca 95030 December 1996

OFFICIAL PUBLICATION OF THE AMERICAN VAULTING ASSOCIATION AIII TING WORI H 11845 SKYLINE BLVD., LOS GATOS, CA 95030 DECEMBER 1996 NEW RULES FOR VAULTING Annual Meeting Schedule Moore on Upper Body Control and more The Voulters of Ice fond pose with their horse, Never Embrace. Photo: courtesy V.I.P. 1997 AVA Friendship Team Priscllla G. Faulkner Application for 1997 Active Status Plans for the 1997 exhibitions are in Please print or type the works and we are looking forward to a Name: Hm Phone: Fax: greatyear promoting vaultingandtiieAV A. Because the status of vaulters changes with Home Address: injuries, college, or fhe decision to play City/State/Zip:. other sports, the application for active sta- Mailing Address: ... tus in Friendship Vaulting team USAmust (If different) City/State/Zip: _ be renewed very winter. Applications will .Weight:. be accepted during the year as vaulters earn Date of B irth: Height their Silver Medals. All vaulters interested Dates of your 1997 Spring Break: Do you have plans?: QYes UNO in participating in the Friendship Team, Date Medal earned: D Silver DGold Club Name: even those on the team tayearinustreLum Coach's Name: . Phone:. the application by Jan. 31, 1997. Number of vaulting practices you attend on your horse. per week How often do you vault on other horses?,.._.. per. If notable to vault regularly, what do you do to keep fit? _ My status will change in: D the summer of 1997 D the fall of 1997 Ul own a Friendship Team uniform LJI own/am buying USA sweats Dl own the red or blue T-shirt Ql own the red polo shirt Ol own the navy sweat shirt / pledge, while working at Friendship Team exhibitions, to vault my best, work cooperatively with the whole group, and be a good ambassador and representative/or the AVA from the time I leave home to the time I return home.