The Economic Outlook for 1979-1980

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Effect of Generics on the Food Market Structure Robert L

Perspectives The Effect of Generics on the Food Market Structure Robert L. Wills and Rosanna L. Mentzer (202) 447-6363 enerics-products in plain packages tion of those products were shipped directly whose stark labels read "GRAPE to stores by manufacturers. GJELLY,'' ''PAPER TOWELS,'' or The USDA analysis compared several "SHORTENING"-have steadily grown characteristics for three groups of product in number on supermarket shelves since be categories: the total sample which contained ing introduced to U.S. consumers in 1977. 384 categories, the 128 product categories Sales of generic products have expanded that had generics in April/May 1979, and while breaking all the rules of successful the product categories that offered generics branded food marketing: extensive adver a year later. This last group contains 54 tising, enticing packaging, and a manufac product categories in addition to those turer's or retailer's logo. categories with generics in 1979. The prod How have generics done it? Their appeal ucts included in this analysis were packaged is price. Generic products are usually priced processed foods because information on 15 to 40 percent below the private label labeling of freshmeats and produce was not (store brand) and branded competition. available. The phenomenal success of these no-frills While around 50 percent of stores carried alternatives has shaken up their product some generic item in 1980, any particular markets. generic item on average was carried by only 8.1 percent of the stores in that year. This Growth of Generics percent of stores expanded between 1979 U.S. food stores responded quickly to the and 1980 for each group presented in table introduction of generics. -

Median and Average Sales Prices of New Homes Sold in United States

Median and Average Sales Prices of New Homes Sold in United States Period Median Average Jan 1963 $17,200 (NA) Feb 1963 $17,700 (NA) Mar 1963 $18,200 (NA) Apr 1963 $18,200 (NA) May 1963 $17,500 (NA) Jun 1963 $18,000 (NA) Jul 1963 $18,400 (NA) Aug 1963 $17,800 (NA) Sep 1963 $17,900 (NA) Oct 1963 $17,600 (NA) Nov 1963 $18,400 (NA) Dec 1963 $18,700 (NA) Jan 1964 $17,800 (NA) Feb 1964 $18,000 (NA) Mar 1964 $19,000 (NA) Apr 1964 $18,800 (NA) May 1964 $19,300 (NA) Jun 1964 $18,800 (NA) Jul 1964 $19,100 (NA) Aug 1964 $18,900 (NA) Sep 1964 $18,900 (NA) Oct 1964 $18,900 (NA) Nov 1964 $19,300 (NA) Dec 1964 $21,000 (NA) Jan 1965 $20,700 (NA) Feb 1965 $20,400 (NA) Mar 1965 $19,800 (NA) Apr 1965 $19,900 (NA) May 1965 $19,600 (NA) Jun 1965 $19,800 (NA) Jul 1965 $21,000 (NA) Aug 1965 $20,200 (NA) Sep 1965 $19,600 (NA) Oct 1965 $19,900 (NA) Nov 1965 $20,600 (NA) Dec 1965 $20,300 (NA) Jan 1966 $21,200 (NA) Feb 1966 $20,900 (NA) Mar 1966 $20,800 (NA) Apr 1966 $23,000 (NA) May 1966 $22,300 (NA) Jun 1966 $21,200 (NA) Jul 1966 $21,800 (NA) Aug 1966 $20,700 (NA) Sep 1966 $22,200 (NA) Oct 1966 $20,800 (NA) Nov 1966 $21,700 (NA) Dec 1966 $21,700 (NA) Jan 1967 $22,200 (NA) Page 1 of 13 Median and Average Sales Prices of New Homes Sold in United States Period Median Average Feb 1967 $22,400 (NA) Mar 1967 $22,400 (NA) Apr 1967 $22,300 (NA) May 1967 $23,700 (NA) Jun 1967 $23,900 (NA) Jul 1967 $23,300 (NA) Aug 1967 $21,700 (NA) Sep 1967 $22,800 (NA) Oct 1967 $22,300 (NA) Nov 1967 $23,100 (NA) Dec 1967 $22,200 (NA) Jan 1968 $23,400 (NA) Feb 1968 $23,500 (NA) Mar 1968 -

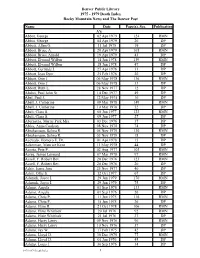

1979 Death Index Rocky Mountain News and the Denver Post Name Date Page(S), Sec

Denver Public Library 1975 - 1979 Death Index Rocky Mountain News and The Denver Post Name Date Page(s), Sec. Publication A's Abbot, George 02 Apr 1979 124 RMN Abbot, George 04 Apr 1979 26 DP Abbott, Allen G. 11 Jul 1975 19 DP Abbott, Bruce A. 20 Apr 1979 165 RMN Abbott, Bruce Arnold 19 Apr 1979 43 DP Abbott, Elwood Wilbur 14 Jun 1978 139 RMN Abbott, Elwood Wilbur 18 Jun 1978 47 DP Abbott, Gertrude J. 27 Apr 1976 31 DP Abbott, Jean Dyer 25 Feb 1976 20 DP Abbott, Orin J. 06 May 1978 136 RMN Abbott, Orin J. 06 May 1978 33 DP Abbott, Ruth L. 28 Nov 1977 12 DP Abdoo, Paul John Sr. 14 Dec 1977 49 DP Abel, Paul J. 12 May 1975 16 DP Abell, J. Catherine 09 Mar 1978 149 RMN Abell, J. Catherine 10 Mar 1978 52 DP Abelt, Clara S. 08 Jun 1977 123 RMN Abelt, Clara S. 09 Jun 1977 27 DP Abernatha, Martie Park Mrs. 03 Dec 1976 37 DP Ables, Anna Coulson 08 Nov 1978 74 DP Abrahamson, Selma R. 05 Nov 1979 130 RMN Abrahamson, Selma R. 05 Nov 1979 18 DP Acevedo, Homero E. Dr. 01 Apr 1978 15 DP Ackerman, Maurice Kent 11 May 1978 44 DP Acosta, Pete P. 02 Aug 1977 103 RMN Acree, Jessee Leonard 07 Mar 1978 97 RMN Acsell, F. Robert Rev. 20 Dec 1976 123 RMN Acsell, F. Robert Rev. 20 Dec 1976 20 DP Adair, Jense Jane 25 Nov 1977 40 DP Adair, Ollie S. -

![[ 1979 ] Part 1 Sec 2 Chapter 22 Assistance to Refugees](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/6401/1979-part-1-sec-2-chapter-22-assistance-to-refugees-986401.webp)

[ 1979 ] Part 1 Sec 2 Chapter 22 Assistance to Refugees

Assistance to refugees 915 Chapter XXII Assistance to refugees Activities of the Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees Increased tensions in various areas in 1979 con- Geneva from 8 to 16 October 1979, stressed the tinued to place further demands on the Office of importance of international protection of refu- the United Nations High Commissioner for gees and called upon all States to respect their Refugees (UNHCR). With the number of refugees rights, especially in regard to the fun damental rising, particularly in Africa and South-East principles of asylum and non-refoulement. It also Asia, UNHCR was called upon to provide interna- stressed the need for assistance to States of first tional protection and material assistance both to asylum in cases involving the large-scale influx asylum-seekers traditionally falling within the of refugees, in accordance with the principle of High Commissioner's mandate and to groups of equitable international burden-sharing, and ex- displaced persons within their country of origin. pressed appreciation for the practical results — On 29 November 1979, the General Assembly including pledges, resettlement opportunities adopted resolutions 34/60, 34/61 and 34/62 con- and plans for establishing refugee processing cerned, respectively, with: the report of the High centres —arising from the Meeting on Refugees Commissioner for the period April 1978 through and Displaced Persons in South-East Asia, con- March 1979; the situation of African refugees, vened by the Secretary-General at Geneva on 20 considered at a pan-African conference on the and 21 July 1979 (see subsection below). The Ex- problem held in May 1979 at Arusha, United ecutive Committee severely condemned recent Republic of Tanzania, partly under UNHCR spon- attacks on refugee camps in southern Africa and sorship; and the report of the Secretary-General expressed the hope that steps would be taken to on a Meeting on Refugees and Displaced Persons protect refugees and assist victims. -

1979-1980 Annual Report -- Academic Policy and Planning Committee R Joel W

1~i,~ "'<.·i RECEIVED I' ~"~"'../ .•.•.•. '..•.•......• ".•. '.•'.. ,~ ' JUL 2 2 1980 1979-1980 Annual Report -- Academic Policy and Planning Committee r Joel W. Russell, Chair OFFICE OF THE DEAN h KRESGE LIBRARY I. Introduction In May 1979 a memorandum was circulated to APPC members outlining areas of potential concern for 1979-80. These areas included: 1. Formulation of committee recommendations for priorities on kypes of new programs to be developed, 2. Establishment of guidelines for, reviewing new programs, 3. Development of a mechanism for reviewing existing programs, 4. Medical school, , 5. Computer literacy, 6. University budget. 7. Reports from special commissions on Entry Year, General Education and Curriculum Flexibility. During 1979-80 the APPC took action in six of these seven areas. Once again the determination of the APPC's role in the review of existing programs was postponed to the next year. II. Medical School The review of the recommendations of the Faculty Council of Health Sciences concerning a future medical school was the most challenging and demanding activity for 1979-80~ An ad hoc Subcommittee of Medical Education was established. The activities of the subcommittee, as reported to the Senate, are summarized in Appendix I. A joint resolution from the APPC and the Faculty Council of Health Sciences recommending a set of basic principles and a specific implementation sequence for establishment of a School of Medicine at Oakland University was approved by the University Senate in April 1980. III. New Masters Level Programs Proposals from the School of Nursing and the Department of Anthropology-Sociology, forestablishrnent of new masters level programs, were discussed using the guidelines for reviewing new programs approved by the committee. -

WHCA Video Log

WHCA Video Log Tape # Date Title Format Duration Network C1 9/23/1976 Carter/Ford Debate #1 (Tape 1) In Philadelphia, Domestic Issues BetaSP, DigiBeta, VHS 90 ABC C2 9/23/1976 Carter/Ford Debate #1 (Tape 2) In Philadelphia, Domestic Issues BetaSP, DigiBeta, VHS 30 ABC C3 10/6/1976 Carter/Ford Debate #2 In San Francisco, Foreign Policy BetaSP, DigiBeta, VHS 90 ABC C4 10/15/1976 Mondale/Dole Debate BetaSP, DigiBeta, VHS 90 NBC C5 10/17/1976 Face the Nation with Walter Mondale BetaSP, DigiBeta, VHS 30 CBS C6 10/22/1976 Carter/Ford Debate #3 At William & Mary, not complete BetaSP, DigiBeta, VHS 90 NBC C7 11/1/1976 Carter Election Special BetaSP, DigiBeta, VHS 30 ABC C8 11/3/1976 Composite tape of Carter/Mondale activities 11/2-11/3/1976 BetaSP, DigiBeta, VHS 30 CBS C9 11/4/1976 Carter Press Conference BetaSP, DigiBeta, VHS 30 ALL C10 11/7/1976 Ski Scene with Walter Mondale BetaSP, DigiBeta, VHS 30 WMAL C11 11/7/1976 Agronsky at Large with Mondale & Dole BetaSP, DigiBeta, VHS 30 WETA C12 11/29/1976 CBS Special with Cronkite & Carter BetaSP, DigiBeta, VHS 30 CBS C13 12/3/1976 Carter Press Conference BetaSP, DigiBeta, VHS 60 ALL C14 12/13/1976 Mike Douglas Show with Lillian and Amy Carter BetaSP, DigiBeta, VHS 60 CBS C15 12/14/1976 Carter Press Conference BetaSP, DigiBeta, VHS 60 ALL C16 12/14/1976 Barbara Walters Special with Peters/Streisand and Jimmy and Rosalynn Carter BetaSP, DigiBeta, VHS 60 ABC Page 1 of 92 Tape # Date Title Format Duration Network C17 12/16/1976 Carter Press Conference BetaSP, DigiBeta, VHS 30 ABC C18 12/21/1976 Carter Press Conference BetaSP, DigiBeta, VHS 30 ALL C19 12/23/1976 Carter Press Conference BetaSP, DigiBeta, VHS 30 ABC C20 12/29/1976 Good Morning America with Carter and Cabinet Members (Tape 1) BetaSP, DigiBeta, VHS 60 ABC C21 12/29/1976 Good Morning America with Carter and Cabinet Members (Tape 2) Digital Files, Umatic 60 ABC C22 1/4/1977 Dinah Shore Show with Mrs. -

Country Term # of Terms Total Years on the Council Presidencies # Of

Country Term # of Total Presidencies # of terms years on Presidencies the Council Elected Members Algeria 3 6 4 2004 - 2005 December 2004 1 1988 - 1989 May 1988, August 1989 2 1968 - 1969 July 1968 1 Angola 2 4 2 2015 – 2016 March 2016 1 2003 - 2004 November 2003 1 Argentina 9 18 15 2013 - 2014 August 2013, October 2014 2 2005 - 2006 January 2005, March 2006 2 1999 - 2000 February 2000 1 1994 - 1995 January 1995 1 1987 - 1988 March 1987, June 1988 2 1971 - 1972 March 1971, July 1972 2 1966 - 1967 January 1967 1 1959 - 1960 May 1959, April 1960 2 1948 - 1949 November 1948, November 1949 2 Australia 5 10 10 2013 - 2014 September 2013, November 2014 2 1985 - 1986 November 1985 1 1973 - 1974 October 1973, December 1974 2 1956 - 1957 June 1956, June 1957 2 1946 - 1947 February 1946, January 1947, December 1947 3 Austria 3 6 4 2009 - 2010 November 2009 1 1991 - 1992 March 1991, May 1992 2 1973 - 1974 November 1973 1 Azerbaijan 1 2 2 2012 - 2013 May 2012, October 2013 2 Bahrain 1 2 1 1998 - 1999 December 1998 1 Bangladesh 2 4 3 2000 - 2001 March 2000, June 2001 2 Country Term # of Total Presidencies # of terms years on Presidencies the Council 1979 - 1980 October 1979 1 Belarus1 1 2 1 1974 - 1975 January 1975 1 Belgium 5 10 11 2007 - 2008 June 2007, August 2008 2 1991 - 1992 April 1991, June 1992 2 1971 - 1972 April 1971, August 1972 2 1955 - 1956 July 1955, July 1956 2 1947 - 1948 February 1947, January 1948, December 1948 3 Benin 2 4 3 2004 - 2005 February 2005 1 1976 - 1977 March 1976, May 1977 2 Bolivia 3 6 7 2017 - 2018 June 2017, October -

Ecological Studies of Vvolves on Isle Royale 1978

ECOLOGICAL STUDIES OF VVOLVES ON ISLE ROYALE ANNUAL REPORT 1978-79 ECOLOGICAL STUDIES OF WOLVES ON ISLE ROYALE* Annual Report - 1978-79 (Covering the twenty-first year of research) by Rolf o. Peterson, Assistant Professor of Biological Sciences, Michigan Technological University Houghton, MI 49931 and Joseph M. Scheidler, Graduate Research Asst. Biological Sciences, Michigan Technological University Houghton, MI 49931 with a special supplement by Philip C. Shelton, Department of Biology, Clinch Valley College of the University of Virginia Wise, VA 24293 30 April 1979 NOT FOR PUBLICATION *Receiving financial support during the current year from: U. S. National Park Service Michigan Department of Natural Resources (Wildlife Division) Boone and Crockett Club National Rifle Association Wildlife Management Institute Camp Fire Conservation Fund, Inc. Quaker Oats Foundation Mr. and Mrs. Kenneth Mason Artwork on cover page by Fred Montague, RFD #5, Monticello, IN 47960 1 INTRODUCTION Now in its 21st year, wolf-moose research on Isle Royale continues to center on a basic study of wolf ecology, with special emphasis on the predator-prey relationship of wolves and moose. For the past five years, Isle Royale has supported the densest wolf population known to exist anywhere. In spite of a high wolf-moose ratio (1 wolf per 20 moose) and habitat completely comprised of mature forests, the moose population has proved to be remarkably durable. In 1979 this 544 km2 (210 mi2) island supported 43 wolves and about 800 moose. Joseph M. Scheidler directed the summer field work in 1978, and in May 1979 will complete his master's thesis, entitled "Population trends and mortality in Isle Royale moose". -

5/1979 Report

Surveyso f Consumer Attitudes 0 ^""^flffi: f Monitoring Economic Change Program F. Thomas Juster, Director George Katona, Founder Richard T. Curtin, Director ' Monitoring Economic Change Program Consumer Survey Program Surveys of Consumer Attitudes May 1979 Quarterly Survey June 11, 1979 INFLATION AND ENERGY PROBLEMS HEIGHTEN PESSIMISM Page HIGHLIGHTS 1 Widespread Declines Recorded 2 Double-Digit Inflation Expected 4 Personal Prospects Pessimistic 5 Business Prospects Weaken 6 Buying Attitudes Weaken 8 Inflation Prompts Divergence in Attitudes 9 Summary Outlook 12 ATTACHMENTS: May Tables and Charts Outstanding Debt Among American Households Consumer Evaluations of Credit Transactions ERRATA: In Table 26, "new fuel efficient models" is incorrectly listed as a negative response when it should appear as a reason why it is a good time to buy a car. * * * The May 1979 Survey included 1,251 interviews conducted between April 25 and May 30, 1979. Institute for Social Research • P.O. Box 1248 • Ann Arbor, Michigan 48106 • (313)763-5224 -1- Highliqhts * In the May 1979 Survey, the Index of Consumer Sentiment was 68.1, down almost 6 Index-points from the February 1979 survey, and almost 15 Index-points below May 1978. * The largest declines from 3 months ago were among families with incomes of $15,000 or more (with the Index falling to 62.1 from 70.9), and the largest declines from a year ago were among households with heads aged 18 to 34 (where the Index declined from 95.1 to 74.6). * Price expectations continue to heighten. In May 1979, 45 percent of all families (54 percent among high-income families) expected prices to go up by 10 percent or more during the next 12 months, up from 26 percent who held a similar view in May 1978 (33 percent among high-income families). -

Supplement to the London Gazette, 22Nd May 1979 6567

SUPPLEMENT TO THE LONDON GAZETTE, 22ND MAY 1979 6567 Lt. A. P. CARRUTH (501794) to be Capt., 15th Feb. Short Serv. Commns. 1979. 23678891 W.O.I (R.S.M.) Michael Daniel MALONEY Lt. R. SHULER (501059) from Special Reg. Commn. to (507575) QUEENS to be 2nd Lt., 2nd Jan. 1979, with be 2nd Lt., 9th Feb. 1979, with seniority 18th Jan. 1974. seniority 2nd Jul. 1974. To be Lt., 2nd Jan. 1979, with To be Lt., 9th Feb. 1979, with seniority 18th Jan. 1976. seniority 2nd Jul. 1976. REGULAR ARMY RESERVE OF OFFICERS 23677009 W.O.I (R.S.M.) John O'GRADY (507633) R.R.F. to be 2nd Lt., 12th Jan. 1979, with seniority 12th Short Serv. Commn. Jul. 1974. To be Lt., 12th Jan. 1979, with seniority 12th Capt. C. O. S. ROBBINS (497899) from Active List to Jul. 1976., be Capt., 13th May 1979. 23832707 W.O.I (R.S.M.) John Simon Jude ROURKE (507127) R. ANGLIAN to. be 2nd Lt., 22nd Feb. 1979, TERRITORIAL AND ARMY VOLUNTEER RESERVE with senirioty 22nd Aug. 1974. To be Lt., 22nd Feb. Group B 1979, with seniority 22nd Aug. 1976. (Postal & Courier Services Section) KING'S DIVISION 2nd Lt. R. D. SNART (504280) to be Lt., 19th Apr. 1979. REGULAR ARMY Lt. Ralph Nigel WALLIS (498293) KINGS from Short Serv. Commn. to be 2nd Lt., 4th Jul. 1978, with seniority 29th Jun. 1974. To be Lt., 4th Jul. 1978, with seniority ROYAL CORPS OF SIGNALS 29th Jun. 1976. REGULAR ARMY 2nd Lt. (on probation) (Undergraduate Cadetship) Alan Capt. -

MAY 1979 COLLEGE of BOCA RATON VOLUME 7, NUMBER 5 GRADUATION '79 Hurray! Hurray! It's Gradu Begin with a Commencement by Served at 7:00

MAY 1979 COLLEGE OF BOCA RATON VOLUME 7, NUMBER 5 GRADUATION '79 Hurray! Hurray! It's Gradu begin with a commencement by served at 7:00. Dancing will ation Day. liturgy at 10:00 a.m. followed follow at 8:30, lasting until 12 midnight. That's the way one feels after by a coffee for graduates and friends. plugging away with · those There will be 127 College of books, lectures and essays for The auditorium is the setting for the actual · graduation Boca Raton graduates and 23 two years, but all good things graduates from Trinity High ceremony at 2:00 p.m. The must come to an end and two School participating in the student speaker delivering the years at the College of Boca commencement exercises. Raton is no exception. welcoming address is Berna dette O'Grady, Co-Editor Two high school students The day is a very special of Pulse, and the commence have completed all four years of event for the graduating ment speaker is Tim Foley of Trinity; of the 127 college stu students because it is the end of the Miami Dolphins. Music will dents graduating, 11 will be a very important part of their be supplied by The Teleman receiving a Bachelor degree for lives and the beginning of the Society. completing four years right next step, wherever itmaytake Following the ceremony is here at C.B.R., while the re them- the President's Reception, from mainder will receive Associate Saturday, May 19, 1979 will 6:00 to 7:00 p.m., with dinner degrees. -

OASIS May 1979

Click for Table of Contents never any State or local tax on bonds. So the 6 percent tax-free yield puts as many dollars away for your child’s future as a 12 percent yield from one of your taxable in- vestments. Frances Per 2. The purchase of the Louisiana Territory, which included what is now the States of Louisiana, Ar- kansas, Missouri, Iowa, North and South Dakota, Nebraska, Kansas, Oklahoma, Montana, most of Min- According to Severn, Fanny nesota, and parts of Wyoming and FRANCES PERKINS: A Member of the Cabinet by Bill Sevem; Haw- Coralie Perkins (not Frances) was Colorado. Six percent certificates born in Boston in the spring of totaling $11,250,000 were issued thorn Books, Inc., New York, N.Y.; 1976; 256 pages. 1882. According to Martin, she was to help meet Napoleon Bonaparte’s born 2 years earlier, in 1880. asking price of $15,000,000. MADAM SECRETARY: Frances Frances herself listed 1882 as her Perkins by George Martin; Hough- 3. In just a little over 3 years, you birth date, but Martin says court- ton Mifflin Company, Boston, house records show 1880 and that would have accumulated about Mass.; 1976; 589 pages. $1,200, or enough to foot the bill for “she subtracted 2 years from her a 7-day trip for two to Ireland, air- When you look at the photo- age.” fare, accommodations, breakfasts, graphs of Frances Perkins, she She enjoyed an uneventful child- tours, etc., included. (Price is based seems the embodiment of the New hood, graduated from high school on a package plan, with departure England Yankee-determined, for- in 1898 and entered Mount Holyoke from Baltimore.) bidding, impassive.