J. Lindsay Almond Interviewer: Larry J

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Endquerynov19.XLSX

11/30/19 Market Account Value Pooled Number Account Name 11/30/19 Book Value Assets F010000001 Land Grant Endowment 400,000.00 0.00 F010000002 Reserve for Loss on Land Grant Endowment 69,697.50 0.00 F010000003 Norman B. Sayne Library Endowment-Humanities 776.54 2,438.43 F010000004 John L.Rhea Library Endowment-Classical Literature 9,518.51 31,379.69 F010000005 Lalla Block Arnstein Library Endowment 5,149.94 17,227.08 F010000006 James Douglas Bruce Library Endowment-English 5,120.00 17,077.22 F010000007 Angie Warren Perkins Library Endowment 1,738.94 5,822.59 F010000008 Stuart Maher Endowment for Technical Library 1,620.81 4,659.33 F010000009 J. Allen Smith Library Endowment 1,102.01 3,678.07 F010000010 Oliver Perry Temple Endowment 24,699.71 82,357.82 F010000011 George Martin Hall Memorial Endowment-Geology 15,307.17 32,507.34 F010000012 Eleanor Dean Swan Audigier Endowment 75,620.98 221,689.58 F010000013 Nathan W. Dougherty Recognition Endowment 23,445.60 57,119.42 F010000014 Better English Endowment 7,018,636.44 12,536,611.52 F010000015 Walters Library Endowment 2,200.00 8,393.10 F010000017 Mamie C. Johnston Library Endowment 5,451.77 18,124.66 F010000018 Ira N. Chiles Library Endowment-Higher Education 21,039.50 58,490.04 F010000019 Human Ecology Library Development Endowment 18,876.01 57,253.50 F010000020 Ellis and Ernest Library Endowment 9,126.87 27,236.56 F010000021 Hamilton National Bank Library Endowment 7,211.34 24,278.80 F010000022 Charles I. -

Cabinet Room #55: April 20

1 NIXON PRESIDENTIAL MATERIALS STAFF Tape Subject Log (rev. 10/08) Conversation No. 55-1 Date: April 20, 1971 Time: 5:17 pm - 6:21 pm Location: Cabinet Room The President met with Barry M. Goldwater, Henry L. Bellmon, John G. Tower, Howard H. Baker, Jr., Robert J. Dole, Edward J. Gurney, J. Caleb Boggs, Carl T. Curtis, Clifford P. Hansen, Jack R. Miller, Clark MacGregor, William E. Timmons, Kenneth R. BeLieu, Eugene S. Cowen, Harry S. Dent, and Henry A. Kissinger [General conversation/Unintelligible] Gordon L. Allott Greetings Goldwater Tower Abraham A. Ribicoff [General conversation/Unintelligible] President’s meeting with John L. McClellan -Republicans -John N. Mitchell -Republicans -Defections -National defense -Voting in Congress National security issues -Support for President -End-the-war resolutions -Presidential powers -Defense budget -War-making powers -Jacob K. Javits bill -John Sherman Cooper and Frank F. Church amendment -State Department 2 NIXON PRESIDENTIAL MATERIALS STAFF Tape Subject Log (rev. 10/08) -Defense Department -Legislation -Senate bill -J. William Fulbright -Vice President Spiro T. Agnew -Preparedness -David Packard’s speech in San Francisco -Popular reaction -William Proxmire and Javits -Vietnam War ****************************************************************************** BEGIN WITHDRAWN ITEM NO. 1 [National Security] [Duration: 7m 55s ] JAPAN GERMANY AFRICA SOVIET UNION Allott entered at an unknown time after 5:17 pm END WITHDRAWN ITEM NO. 1 [To listen to the segment (29m15s) declassified on 02/28/2002, -

A Directory of Tennessee Agencies

Directory of Tennessee Agencies Abraham Lincoln Library and Museum African American Heritage Society Lincoln Memorial University McLemore House Museum Cumberland Gap Parkway P. O. Box 2006 P.O. Box 17684 Harrogate, TN 37752-2006 Nashville, TN 37217 423-869-6235 Acuff-Ecoff Family Archives African American Historical & P. O. Box 6764 Genealogical Society Knoxville, TN 37914-0764 Tennessee Chapter, AAHGS 865-397-6939 Nutbush, TN 38063 731-514-0130 Adams Museum African Roots Museum Bell School Building 12704 Highway 19 7617 Highway 41N Mary Mills Adams, TN 37010 1777 West Main Street Franklin, TN 37064 615-794-2270 Adventure Science Center Alex Haley House Museum THC 800 Fort Negley Boulevard Alex Haley Museum Association Nashville, TN 37203 200 S. Church Street 615-862-5160 P. O. Box 500 Henning, TN 38041 731-738-2240 African American Community Allandale Committee and Information Center Friends of Allandale/City of Kingsport Connie Baker 4444 West Stone Drive P.O. Box 455 Kingsport, TN 37660 Elizabethton, TN 37643 423-229-9422 423-542-8813 African American Cultural Alliance American Association for State and P.O. Box 22173 Local History Nashville, TN 37202 1717 Church Street 615-329-3540 Nashville, TN 37203-2991 615-230-3203 African American Genealogical and American Baptist College Historical Society T. L. Holcomb Library Dr. Tommie Morton Young 1800 Baptist World Center Drive P.O. Box 281613 Nashville, TN 37207 Nashville, TN 37228 615-687-6904 615-299-5626 Friday, October 13, 2006 Page 1 of 70 American Legion Anubis Society Department of Tennessee 1816 Oak Hill Drive 215 8th Avenue North Kingston, TN 37763 Nashville, TN 37203 615-254-0568 American Museum of Science & Energy Appalachian Caverns Foundation 300 South Tulane Ave. -

Administrative Officials, Classified by Functions

i-*-.- I. •^1 TH E BO OK OF THE STATES SUPPLEl^ENT II JULY, 1961 ADMINISTRATIVE OfnciAts Classified by Functions m %r^ V. X:\ / • ! it m H^ g»- I' # f K- i 1 < 1 » I'-- THE BOOK ••<* OF THE STATES SUPPLEMENT IJ July, 1961 '.•**••** ' ******* ********* * * *.* ***** .*** ^^ *** / *** ^m *** '. - THE council OF STATE fiOVERNMEIITS ADMINKJTRATIV E O FFICIALS Classified by Fun ctions The Council of State Governments Chicago . ^ V /fJ I ^. sir:. \ i i- m m f. .V COPYRIGHT, 1961, BY - The Council of State Governments 131.3 East Sixtieth Street Chicago 37, Illinois m ¥ m-'^ m.. Library of Congress Catalog Card Number: 35-11433 PRINTED IN THE UNITED STATES OF AUERICA «; Price, $2.50 \V FOREWORD This publication is the second of two Supplements to the 196Q-61 edition of The Book of the States, the biennial reference work on the organizationj working methods, financing and services of all the state governments. The present volimie, SupplementJI, based on information received from the states up to May 15, 1961, contains state-by-state rosters of principal administrative officials of the states, whether elected or appointed, and the Chief Justices of the Supreme Cou?&. It concludes with a roster of interstate agencies in many functional fields. Supplement I, issued in February, 1961, listed sill state officials and Supreme Court Justices elected by ^statewid'*., popular vote, and the members and officers of the legislatures. _j The Council of State Governments gratefully acknowledges the invaluable help of the members of the legislative service agencies and the many other state officials who have furnished the information used in this publication. -

1969 NGA Annual Meeting

Proceedings OF THE NATIONAL GOVERNORS' CONFERENCE 1969 SIXTY-FIRST ANNUAL MEETING BROADMOOR HOTEL • COLORADO SPRINGS, COLORADO AUGUST 31-SEPTEMBER 3, 1969 THE NATIONAL GOVERNORS' CONFERENCE IRON WORKS PIKE LEXINGTON, KENTUCKY 40505 THE COUNCil OF S1'ATE GOVERNMENTS IRON WORKS PIKE LEXINGTON, KENTUCKY 40511 J Published by THE NATIONAL GOVERNORS' CONFERENCE IRON WORKS PIKE LEXINGTON, KENTUCKY 40505 CONTENTS Executive Committee Rosters v Other Committees of the Conference vi Governors and Guests in Attendance viii Program of the Annual Meeting xi Monday Sessions-September 1 Welcoming Remarks-Governor John A. Love 1 Address of the Chairman-Governor Buford Ellington 2 Adoption of Rules of Procedure . 4 Remarks of Monsieur Pierre Dumont 5 "Governors and the Problems of the Cities" (including reports and policy statements of the Committee on Community Development and Urban Relations), Governor Richard J. Hughes presiding .. 6 Remarks of Secretary George Romney . .. 15 "Revenue Sharing" (including reports and policy statements of the Committee on Executive Management and Fiscal Affairs), Governor Daniel J. Evans presiding . 33 Remarks of Dr. Arthur F. Burns .. 36 Remarks of Vice-President Spiro T. Agnew 43 State Ball Remarks of Governor John A. Love 57 Remarks of Governor Buford Ellington 57 Address by the President of the United States 58 Tuesday Sessions-September 2 "Major Issues in Human Resources" (including reports and policy statements of the Committee on Human Resources), Governor Nelson A. Rockefeller presiding . 68 Remarks of Secretary George P. Shultz 87 "Transportation" (including reports and policy statements of the Committee on Transportation, Commerce, and Technology), Governor John A. Love presiding 95 Remarks of Secretary John A. -

Clement, Frank Goad (1920-1969) Papers, 1920-1969

CLEMENT, FRANK GOAD (1920-1969) PAPERS, 1920-1969 Processed by: Harry A. Stokes Archives & Manuscripts Unit Technical Services Section Tennessee State Library and Archives Accession Number: 94-007 Date Completed: May 15, 1995 Location: XIX-A-E Microfilm Accession Number: 1512 INTRODUCTION This finding aid covers the personal papers of Frank Goad Clement (1920-1969). Mr. Clement served three terms as Governor of Tennessee: 1953-1955; 1955-1959; and 1963-1967. Previously he was a former F. B. I. agent, Chief Counsel for the State Public Utilities Commission; and a practicing Attorney in Dickson and Nashville, Tennessee. The Tennessee State Library and Archives received these materials on March 14, 1991, from the Clement family, through the agency of F. Lynne Bachleder for the State of Tennessee via contract with Designing Eye of Martinsville, Virginia. Mr. Clement’s papers include certificates, clippings, correspondence, financial records, invitations and programs, legal files, political campaign materials, photographs, schedules, and scrapbooks and speeches, all reflective of his professional career. Mr. Clement’s papers, along with other Clement historical artifacts, were housed for many years in the old Halbrook Hotel in Dickson, Tennessee. Mr. Clement’s mother, Maybelle Goad Clement, and her parents formerly owned and operated the Halbrook Hotel. The Frank G. Clement artifacts are presently in storage at the Tennessee State Museum. The inclusive dates of the material is for the period 1920 through 1969, although the bulk of the material is concentrated between 1952 through 1969. Many of the clippings in the scrapbooks were loose and had to be reaffixed to the pages. -

UTM's Emergency Response Plan

EMERGENCY RESPONSE PLAN Note: This is the Media Version of the Emergency Response Plan. Some of the information in this document has been omitted due to confidentiality purposes. Revised March 2020 UTM Safety & Health Procedures, Subject F: Emergency Response Plan Table of Contents List of Appendices........................................................................................................... Page 2 Executive Policy ...................................................................................................................... 3 1. Purpose .............................................................................................................................. 4 2. Emergency Defined ............................................................................................................ 4 3. Initial Response .................................................................................................................. 5 4. Declaration of Emergency .................................................................................................. 5 5. Incident Management ......................................................................................................... 5 6. Chain of Command/Emergency Policy Group ................................................................... 5 7. Emergency Operations Center ........................................................................................... 6 8. Emergency Management Group ........................................................................................ -

Tennessee State Library and Archives GOVERNOR BUFORD

State of Tennessee Department of State Tennessee State Library and Archives 403 Seventh Avenue North Nashville, Tennessee 37243-0312 GOVERNOR BUFORD ELLINGTON PAPERS (First Term) 1959-1963 GP 48 Processed by: Archival Technical Services INTRODUCTION This finding aid covers the gubernatorial papers of Tennessee Governor Buford Ellington, who served from 1959-1963 and 1967-1971. It consists of 121 boxes of materials that consist of correspondence, subject files, invitations, audits, bills, extraditions, and requisitions. There are no restrictions on the use of the materials and researchers may make copies of individual items for individual or scholarly use. BIOGRAPHICAL NOTE Governor Buford Ellington Born in Mississippi in 1907, Ellington became a farmer and merchant, also serving as agriculture commissioner for six years under Frank Clement, and as a member of the legislature before he was elected governor in 1958. he and Clement led the Democratic party and alternated the executive chair for eighteen years. Initially a segregationist, Ellington later reversed his position. Peaceful, successful nonviolent sit-ins in Nashville were among the earliest and best organized in the nation. His terms saw constitutional changes, reorganization and reduction of state government, liberalization of liquor laws and repeal of the anti-evolution law. He died in 1972. Source: Tennessee Blue Book, 1999-2000, page 484. CONTAINER LIST Box 1 Departmental Correspondence 1 Adjutant General 1959 2 Adjutant General 1960 3 Adjutant General (January-June) 1961 -

New Proposals for 1970: ACIR State Legislative Program

ACIR STATE LEGISLATIVE PROGRAM 14 ORV COMMISSION ON INTERGOVERNMENTAL RELAT~~~~&~- ' WASHINGTON, D. C. - 2 057<iy~2~~ggg~~3~~~3 I JULY 1969 M- 45 ADVISORY COMMISSION ON INTERGOVERNMENTAL RELATIONS June 1969 Private Citizens: Fanis Bryant, Jacksonville, Florida, Chairman Alexander Heard, Nashville, Tennessee Dorothy I. Cline, Albuquerque, New Mexico Members of United States Senate: Sam J. Ervin, Jr., North Carolina Karl E. Mundt, South Dakota Edmund S. Muskie, Maine Members of United States House of Representatives: Florence P. Dwyer, Mrs., New Jersey L. H. Fountain, North Carolina A1 Ullman, Oregon Officers of Executive Branch, Federal Government: Robert H. Finch, Secretary of Health, Education, and Welfare Robert P. Mayo, Director of Bureau of the Budget George Romney, Secretary of Housing and Urban Development Governors: Buford Ellington, Tennessee Warren E. Hearnes, Missouri Nelson A. Rockefeller, New York Raymond P. Shafer, Pennsylrania Mayors: C. Beverly Briley ,Nashville, Tennessee Richard G. Lugar, Indianapolis, Indiana Jack Maltester, San Leandro, California William F. Walsh, Syracuse, New York embers of State Legislative Bodies: W. Russell Arrington, Senator, Illinois Robert P. Knowles, Senator, Wisconsin Jesse M. Unruh, Assemblyman, California Elected County Officials: John F. Dever, Middlesex County, Massachusetts Edwin C. Michaelian, Westchester County, New York Lawrence K. Roos, St. Louis County, Missouri New Proposals For 1970 ACIR STATE LEGISLATIVE PROGRAM ADVISORY COMMISSION ON INTERGOVERNMENTAL RELATIONS WASHINGTON, D. C. 20575 JULY 1%9 M- 45 The Advisory Commission on Intergovernmental Relations is a permanent, bipartisan body established by Act of Congress in 1959 to give continuing study to the relationships among local, State, and national levels of government. The Commission's membership, representing the legislative and executive branches of the three levels of government and the public at large, is listed on the inside of the front cover. -

State and Territorial Officers

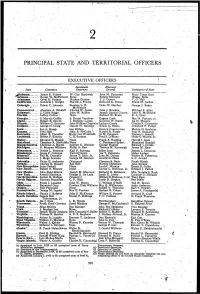

r Mf-.. 2 PRINCIPAL STATE AND TERRITORIAL OFFICERS EXECUTIVE- OFFICERS • . \. Lieutenant Attorneys - Siaie Governors Governors General Secretaries of State ^labama James E. Folsom W. Guy Hardwick John M. Patterson Mary Texas Hurt /Tu-izona. •. Ernest W. McFarland None Robert Morrison Wesley Bolin Arkansas •. Orval E. Faubus Nathan Gordon T.J.Gentry C.G.Hall .California Goodwin J. Knight Harold J. Powers Edmund G. Brown Frank M. Jordan Colorajlo Edwin C. Johnson Stephen L. R. Duke W. Dunbar George J. Baker * McNichols Connecticut... Abraham A. Ribidoff Charles W. Jewett John J. Bracken Mildred P. Allen Delaware J. Caleb Boggs John W. Rollins Joseph Donald Craven John N. McDowell Florida LeRoy Collins <'• - None Richaid W. Ervin R.A.Gray Georgia S, Marvin Griffin S. Ernest Vandiver Eugene Cook Ben W. Fortson, Jr. Idaho Robert E. Smylie J. Berkeley Larseri • Graydon W. Smith Ira H. Masters Illlnoia ). William G. Stratton John William Chapman Latham Castle Charles F. Carpentier Indiana George N. Craig Harold W. Handlpy Edwin K. Steers Crawford F.Parker Iowa Leo A. Hoegh Leo Elthon i, . Dayton Countryman Melvin D. Synhorst Kansas. Fred Hall • John B. McCuish ^\ Harold R. Fatzer Paul R. Shanahan Kentucky Albert B. Chandler Harry Lee Waterfield Jo M. Ferguson Thelma L. Stovall Louisiana., i... Robert F. Kennon C. E. Barham FredS. LeBlanc Wade 0. Martin, Jr. Maine.. Edmund S. Muskie None Frank Fi Harding Harold I. Goss Maryland...;.. Theodore R. McKeldinNone C. Ferdinand Siybert Blanchard Randall Massachusetts. Christian A. Herter Sumner G. Whittier George Fingold Edward J. Cronin'/ JVflchiitan G. Mennen Williams Pliilip A. Hart Thomas M. -

290 [73 ST AT, Public Law 86.143 Resolved Hy the Seriate and House of Representatives of the United States of America in Congres

290 PUBLIC LAW 86-143-AUG. 7, 1959 [73 ST AT, Public Law 86.143 JOINT RESOLUTION August 7, 1959 [H. J. Res. 280] Consenting to an interstate compact to conserve oil and gas. Resolved hy the Seriate and House of Representatives of the United Oil and compact. States of America in Congress assembled, That the consent of Con Extension. gress is hereby given to an extension and renewal for a period of four years from September 1, 1959, of the interstate compact to conserve oil and gas, which was signed in the city of Dallas, Texas, the 16th day of February 1935 by the representatives of Oklahoma, Texas, California, and New Mexico, and at the same time and place was signed by the representatives, as a recommendation for approval to the Governors and Legislatures of the States of Arkansas, Colorado, Illinois, Kansas, and Michigan, and prior to August 27, 1935, said compact was presented to and approved by the Legislatures and Gov ernors of the States of New Mexico, Kansas, Oklahoma, Illinois, Colo rado, and Texas, wiiich said compact so approved by the six States last above named was deposited m the Department of State of the United States, and thereafterwards Congress gave its consent to said 49 Stat. 939. compact by H.J. Res. 407 (Public Resolution Numbered 64), for a eriod of two years and thereafterwards said compact was extended gy Governors of the compacting States and Congress gave its consent thereto as follows: by S.J. Res. 183 (Public Resolution Numbered 50 Stat. 617. S3 Stat. -

Past Governors of Tennessee 489

PAST GOVERNORS OF TENNESSEE 489 Past Governors Of Tennessee William Blount, 1790-1795, Democrat (territorial governor). Born in North Carolina in 1749, Blount served in the Continental Congress 1783-1784 and 1786-1787. In 1790, President Washington appointed him governor of the newly formed Territory South of the River Ohio, formerly part of North Carolina. While governor, Blount was also Indian affairs superinten- dent and negotiated, among others, the Treaty of the Holston with the Cherokees. His new government faced formidable problems, intensified by conflicts created by European/Indian contact. In 1795, Blount called a constitutional convention to organize the state, and Tennessee entered the Union the next year. Blount represented the new state in the U.S. Senate, and after expulsion from that body on a conspiracy charge, served in the state Senate. He died in 1800. John Sevier, 1796-1801; 1803-1809, Democrat. Born in Virginia in 1745, Sevier as a young man was a suc- cessful merchant. Coming to a new settlement on the Holston River in 1773, he was one of the first white settlers of Tennessee. He was elected governor of the state of Franklin at the end of the Revolutionary War, and as such became the first governor in what would be Tennessee. When statehood was attained in 1796, Sevier was elected its first governor. He served six terms totaling twelve years. While governor he negoti- ated with the Indian tribes to secure additional lands for the new state and opened new roads into the area to encourage settlement. At the close of his sixth term he was elected to the state Senate, and then to Congress.