Takings and Beyond: Implications for Regulation

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Practice of Dissent in the Supreme Court, 105 Yale Law Journal

Vanderbilt University Law School Scholarship@Vanderbilt Law Vanderbilt Law School Faculty Publications Faculty Scholarship 1996 The rP actice of Dissent in the Supreme Court Kevin M. Stack Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarship.law.vanderbilt.edu/faculty-publications Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation Kevin M. Stack, The Practice of Dissent in the Supreme Court, 105 Yale Law Journal. 2235 (1996) Available at: http://scholarship.law.vanderbilt.edu/faculty-publications/227 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Faculty Scholarship at Scholarship@Vanderbilt Law. It has been accepted for inclusion in Vanderbilt Law School Faculty Publications by an authorized administrator of Scholarship@Vanderbilt Law. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Practice of Dissent in the Supreme Court Kevin M. Stack The United States Supreme Court's connection to the ideal of the rule of law is often taken to be the principal basis of the Court's political legitimacy.' In the Supreme Court's practices, however, the ideal of the rule of law and the Court's political legitimacy do not always coincide. This Note argues that the ideal of the rule of law and the Court's legitimacy part company with respect to the Court's practice of dissent. Specifically, this Note aims to demonstrate that the practice of dissent-the tradition of Justices publishing their differences with the judgment or the reasoning of their peers 2-cannot be justified on the basis of an appeal to the ideal of the rule of law, but that other bases of the Court's political legitimacy provide a justification for this practice. -

Faculty Activities

Faculty Activities left to right Bruce Ackerman Anne L. Alstott Ian Ayres Jack M. Balkin Robert A. Burt Bruce Ackerman Mobilizing Heterosexual Support for Gay August 18, 2004, at 52 (with B. Nalebuff); Appointments Rights”and “A Separate Crime of Reckless Dialing for Thieves, Forbes, April 19, 2004, Board of Trustees, Center for American Sex”; UMKC Law School, “Reckless Sex”; at 76 (with B. Nalebuff); Going, Going, Progress. Hazard Lecture, Pembroke Hill High School, Google, Wall St. J.,August 20, 2004, at A12 Publications “Can Creativity Be Taught? Why Not?”; (with B. Nalebuff). Thomas Jefferson Counts Himself Into the Duke Law School,“Tradable Patent Presidency, 90 U. Va. L. Rev. 551 (2004) (with Permits”;The British Council, Santiago, Jack M. Balkin D. Fontana); This Is Not a War, 113 Yale L.J. Chile,“Using Anonymity to Keep the Public Lectures and Addresses 1871 (2004); A Precedent-Setting and Candidates Symmetrically Informed”; University of Delaware Conference on Appearance, Center for American Buenos Aires, Argentina,“The Refund Brown v. Board of Education,“Brown v. Progress (website), April 8, 2004; The Booth”; Helsinki Conference on Behavioral Board of Education and Social Thinking Voter, Prospect,May 2004, at 15 Economics,“Comment on Christine Jolls”; Movements”; Information Technology and (with J. Fishkin); 2-for-1 Voting, N.Y.Times, NAACP National Meeting, Philadelphia, Society Colloquium, NYU Law School, May 5, 2004, at A27; Just Imagine, A Day Off “Disparate Impact Litigation in “Virtual Liberty: Freedom to Design and Devoted to Fulfilling a Democratic Duty, Automobile Finance”; NBER Summer Law Freedom to Play in Virtual Worlds.” Philadelphia Inquirer, June 20, 2004 and Economics Institute,“To Insure Publications (with J. -

American Legal Thought from Premodernism to Postmodernism: an Intellectual Voyage

American Legal Thought from Premodernism to Postmodernism: An Intellectual Voyage Stephen M. Feldman Oxford University Press American Legal Thought from Premodernism to Postmodernism This page intentionally left blank American Legal Thought from Premodernism to Postmodernism 1 An IntellectualVoyage 4 Stephen M. Feldman New York Oxford Oxford University Press Oxford University Press Oxford New York Athens Auckland Bangkok Bogotá Buenos Aires Calcutta Cape Town Chennai Dar es Salaam Dehli Florence Hong Kong Istanbul Karachi Kuala Lumpur Madrid Melbourne Mexico City Mumbai Nairobi Paris São Paulo Singapore Taipei Tokyo Toronto Warsaw and associated companies in Berlin Ibadan Copyright © by Oxford University Press, Inc. Published by Oxford University Press, Inc. Madison Avenue, New York, New York Oxford is a registered trademark of Oxford University Press All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior permission of Oxford University Press. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Feldman, Stephen M., – American legal thought from premodernism to postmodernism: an intellectual voyage / Stephen M. Feldman. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN ---X (cl.); ISBN --- (pbk.) . Jurisprudence—United States. Law—United States—Philosophy. Postmodernism. I. Title. KF.F .—DC - Printed in the United States of America on acid-free paper To my family, Laura, Mollie, and Samuel This page intentionally left blank Acknowledgments As I have learned over the past few years, deciding whom to thank for assistance in the writing of a book can be a daunting task. Of course, I especially thank those individuals who commented on drafts of this book: Steven D. -

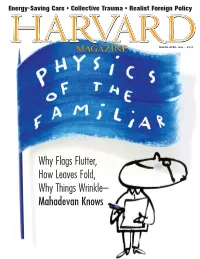

Why Flags Flutter, How Leaves Fold, Why Things Wrinkle– Mahadevan Knows Certifi Ed Pre-Owned Three Years Old BMW and Still Better Than Most Things New

Energy-Saving Cars • Collective Trauma • Realist Foreign Policy MARCH-APRIL 2008 • $4.95 Why Flags Flutter, How Leaves Fold, Why Things Wrinkle– Mahadevan Knows Certifi ed Pre-Owned Three years old BMW and still better than most things new. bmwusa.com/cpo The Ultimate 1-800-334-4BMW Driving Machine® After rigorous inspections only the most pristine vehicles are chosen. That’s why we offer a warranty for up to 6 years or 100,000 miles.* In fact, a Certifi ed Pre-Owned BMW looks so good and performs so well it’s hard to believe it’s pre-owned. But it is, we swear. bmwusa.com/cpo Certifi ed by BMW Trained Technicians / BMW Warranty / BMW Leasing and Financing / BMW Roadside Assistance† Pre-Owned. We Swear. *Protection Plan provides coverage for two years or 50,000 miles (whichever comes ¿ rst) from the date of the expiration of the 4-year/50,000-mile BMW New Vehicle Limited Warranty. †Roadside Assistance provides coverage for two years (unlimited miles) from the date of the expiration of the 4-year/unlimited-miles New Vehicle Roadside Assistance Plan. See participating BMW center for details and vehicle availability. For more information, call 1-800-334-4BMW or visit bmwusa.com. ©2008 BMW of North America, LLC. The BMW name and logo are registered trademarks. 130764_1_v1 1 1/17/08 7:11:31 PM MARCH-APRIL 2008 VOLUME 110, NUMBER 4 FEATURES 30 Saving Money, Oil, and the Climate How to wean ourselves from imported petroleum by powering our vehicles with environmentally benign electricity by Michael B. -

Harvard Law School Faculty 20–21

Harvard Law School Faculty – 1 Professors and Assistant Professors of Law 3 Professors Emeriti and Emeritae 48 Affiliated Harvard University Faculty 55 Visiting Professors of Law 61 Climenko Fellows 73 Lecturers on Law 75 Endowed Chairs at Harvard Law School 95 2 HARVARD LAW SCHOOL FacULTY 2020–2021 Professors and Assistant Professors of Law William P. Alford Jerome A. and Joan L. Cohen Professor of East Asian Legal Studies Courses: Engaging China, Fall 2020; The Comparative Law Workshop, Fall 2020; Comparative Law: Why Law? Lessons from China, Spring 2021. Research: Chinese Legal History and Law, Comparative Law, Disability Law, International Trade, Law and Development, Legal Profession, Transnational/Global Lawyering, WTO. Representative Publications: An Oral History of Special Olympics in China in 3 volumes (William P. Alford, Mei Liao, and Fengming Cui, eds., Springer 2020) Taiwan and international Human Rights: A story of Transformation (Jerome A. Cohen, William P. Alford, and Chang-fa Lo, eds., Springer 19); Prospects for The Professions in China (William P. Alford, Kenneth Winston & William C. Kirby eds., Routledge 1); William P. Alford, To Steal A Book Is an Elegant Offense: Intellectual Property Law in Chinese Civilization (Stanford Univ. Press 1995). Education: Amherst College B.A. 197; St. John’s College, Cambridge University LL.B. 197; Yale University M.A. 1974; Yale University M.A. 1975; Harvard Law School J.D. 1977. Appointments: Henry L. Stimson Professor of Law, 199–18; Director, East Asian Legal Studies, 199– present; Vice Dean for the Graduate Program and International Legal Studies, 2002–2020; Chair, Harvard Law School Project on Disability, 4–present; Jerome A. -

The Liberal Tradition of the Supreme Court Clerkship: Its Rise, Fall, and Reincarnation? William E

Vanderbilt Law Review Volume 62 | Issue 6 Article 3 11-2009 The Liberal Tradition of the Supreme Court Clerkship: Its Rise, Fall, and Reincarnation? William E. Nelson Harvey Rishikof I. Scott esM singer Michael Jo Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.law.vanderbilt.edu/vlr Part of the Supreme Court of the United States Commons Recommended Citation William E. Nelson, Harvey Rishikof, I. Scott eM ssinger, and Michael Jo, The Liberal Tradition of the Supreme Court Clerkship: Its Rise, Fall, and Reincarnation?, 62 Vanderbilt Law Review 1747 (2019) Available at: https://scholarship.law.vanderbilt.edu/vlr/vol62/iss6/3 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Scholarship@Vanderbilt Law. It has been accepted for inclusion in Vanderbilt Law Review by an authorized editor of Scholarship@Vanderbilt Law. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Liberal Tradition of the Supreme Court Clerkship: Its Rise, Fall, and Reincarnation? William E. Nelson, Harvey Rishikof L Scott Messinger, Michael Jo 62 Vand. L. Rev. 1749 (2009) This Article presents the first comprehensive empirical study of the post-clerkship employment of law clerks at the Supreme Court from 1882 to the present, and it uses that data to flesh out a historical and institutional interpretation of the clerkship and the recent politicalpolarization of the Court more generally. The liberal tradition of the clerkship arose out of Louis Brandeis's vision of former law clerks serving a progressive legal agenda, a tradition that Felix Frankfurter helped institutionalize while striving to remove ideological bias. With the advent of a conservative bloc on the Court, this tradition has waned, due to the emergence of markedly partisanpatterns in the Justices' hiring of clerks and post- clerkship careers in academia, private practice, and government. -

Degrees of Change in THIS ISSUE

SUMMER 2012 Harvard Lawbulletin In a new environment, training lawyers to solve problems together Degrees of Change IN THIS ISSUE volume 63 | number 2 | summer 2012 1 FROM THE DEAN 2 LETTERS 3 INSIDE THE CLASSROOM Reading groups offer students (and professors) opportunities to cover new ground. 5 THE CLINICAL CLASSROOM N O Students design appeals process for 3 page 34 new consumer watchdog agency. PETER AAR 6 STUDENT ENDEAVORS An enterprising organization 7 FACULTY VIEWPOINTS 20a The Ripple Effect Exploring Citizens United’s effect on a wide spectrum of stakeholders A watershed year for the Environmental 9 SYMPOSIUM Law Program A global gathering to celebrate Frank Michelman ’60 10 ON THE BOOKSHELVES 26a In the Driver’s Seat Shugerman explores the history of The changing role of the general counsel judicial selection in the U.S.; Mack reframes the story of America’s civil rights lawyers; Goldsmith points to 31a Closing the Deal a robust balance of power and new forms of presidential accountability in HLS grads are at the center of a record the fight against terrorism. $25 billion mortgage agreement. 16 THE MATRIX A sampling of HLS alumni in the na- tional security field since 9/11 34a The Way We Live Now 18 REPRISE A day in the life of the school’s new living The revival of a student-funded fel- and learning center lowship that has yielded rich returns 39 CLASS NOTES assistant dean for communications After death camps, a force for life; At- Robb London ’86 ticus Finch with a laptop; Leading my editor Emily Newburger hometown; Giving counsel to Ethiopia managing editor 57 HLS AUTHORS Linda Grant editorial assistance 58 TRIBUTE Sophy Bishop, Jill Greenfield ’12, Professor Charles M. -

Roe Rage: Democratic Constitutionalism and Backlash

Roe Rage: Democratic Constitutionalism and Backlash Robert Post* Reva Siegel* Progressive confidence in constitutional adjudication peaked during the Warren Court and its immediate aftermath. Courts were celebrated as "fora of principle,"' privileged sites for the diffusion of human reason. But progressive attitudes toward constitutional adjudication have recently begun to splinter and diverge. 2 Some progressives, following the call of "popular constitutionalism," have argued that the Constitution should be taken away from courts and restored to the people.3 Others have empha- sized the urgent need for judicial caution and minimalism.4 One of the many reasons for this shift is that progressives have be- come fearful that an assertive judiciary can spark "a political and cultural backlash that may ... hurt, more than" help, progressive values.5 A gen- eration ago, progressives responded to violent backlash against Brown v. Board of Education6 by attempting to develop principles of constitutional * David Boies Professor of Law, Yale University. Nicholas deB. Katzenbach Professor of Law, Yale University. Many thanks to Bruce Ackerman, Jack Balkin, David Barron, Eric Citron, Bill Eskridge, Owen Fiss, Barry Friedman, Sarah Gordon, Mark Graber, Michael Graetz, David Hollinger, Dawn Johnsen, Amy Kapczyn- ski, Michael Klarman, Scott Lemieux, Sandy Levinson, Joanne Meyerowitz, Sasha Post, Judith Resnik, Neil Siegel, and Christine Stansell for comments on the manuscript. We had the pleasure of working with an extraordinary group of Harvard and Yale research assis- tants on this Essay, including Nick Barnaby, Robert Cacace, Kathryn Eidmann, Rebecca Engel, Sarah Hammond, Kara Loewentheil, Sandra Pullman, Sandeep Ramesh, Sandra Vasher, and Justin Weinstein-Tull. ' Ronald Dworkin, The Forum of Principle, 56 N.Y.U.