NORM DICKS Alma Mater Comes of Age

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Miles Poindexter Papers, 1897-1940

Miles Poindexter papers, 1897-1940 Overview of the Collection Creator Poindexter, Miles, 1868-1946 Title Miles Poindexter papers Dates 1897-1940 (inclusive) 1897 1940 Quantity 189.79 cubic feet (442 boxes ) Collection Number 3828 (Accession No. 3828-001) Summary Papers of a Superior Court Judge in Washington State, a Congressman, a United States Senator, and a United States Ambassador to Peru Repository University of Washington Libraries, Special Collections. Special Collections University of Washington Libraries Box 352900 Seattle, WA 98195-2900 Telephone: 206-543-1929 Fax: 206-543-1931 [email protected] Access Restrictions Open to all users. Languages English. Sponsor Funding for encoding this finding aid was partially provided through a grant awarded by the National Endowment for the Humanities Biographical Note Miles Poindexter, attorney, member of Congress from Washington State, and diplomat, was born in 1868 in Tennessee and grew up in Virginia. He attended Washington and Lee University (undergraduate and law school), receiving his law degree in 1891. He moved to Walla Walla, Washington, was admitted to the bar and began his law practice. He entered politics soon after his arrival and ran successfully for County Prosecutor as a Democrat in 1892. Poindexter moved to Spokane in 1897 where he continued the practice of law. He switched to the Republican Party in Spokane, where he received an appointment as deputy prosecuting attorney (1898-1904). In 1904 he was elected Superior Court Judge. Poindexter became identified with progressive causes and it was as a progressive Republican and a supporter of Theodore Roosevelt that he was elected to the House of Representatives in 1908 and to the Senate in 1910. -

History of the Washington Legislature, 1854-1963

HISTORY of the History of the Washington LegislatureHistory of the Washington 1854 -1963 History of the Washington LegislatureHistory of the Washington 1854 -1963 WASHINGTONWASHINGTON LEGISLATURELEGISLATURE 18541854 - - 1963 1963 by Don Brazier by Don Brazier by Don Brazier Published by the Washington State Senate Olympia, Washington 98504-0482 © 2000 Don Brazier. All rights reserved. No portion of this book may be reproduced or used in any form, or by any means, without prior written permission of the author. 10987654321 Printed and bound in the United States i Acknowledgments A lot of people offered encouragement and moral support on this project. I cannot name them all, but a few are worthy of mention. Nancy Zussy, Ellen Levesque, Gayle Palmer, and Shirley Lewis at the Washington State Library were extremely helpful. Sid Snyder and Ralph Munro have each been treasured friends for more than 30 years. They probably know more about the history of this legislature than any other two people. I am honored and flattered that they would write brief forwards. There are many who have offered encouragement as I spent day after day seated at the microfilm machine in the Washington Room at the library. It is a laborious task; not easy on the eyes. They include my sons, Bruce and Tom, Scott Gaspard, Representative Shirley Hankins, Shelby Scates, Mike Layton, the late Gerald Sorte, Senator Bob Bailey, Sena- tor Ray Moore and his wife Virginia, Rowland Thompson, and numerous others who I know I’ve forgotten to mention. My special gratitude goes to Deanna Haigh who deciphered my handwriting and typed the manuscript. -

A Coalition to Protect and Grow National Service

A Coalition to Protect and Grow National Service Membership Overview About Voices for National Service PARTNERING TO PROTECT AND EXPAND NATIONAL SERVICE Voices for National Service is a coalition of national, state and local service organizations working together to build bipartisan support for national service, develop policies to expand and strengthen service opportunities for all Americans, and to ensure a robust federal investment in the Corporation for National and Community Service (CNCS). Voices for National Service was founded in 2003 in the wake of a successful campaign to save AmeriCorps from sudden and significant proposed cuts. The national service field organized and launched a successful “Save AmeriCorps” campaign that ultimately restored--and in fact increased--federal funding for CNCS and AmeriCorps within one year. Following the successful 2003 Save AmeriCorps campaign, the national service community established Voices for National Service, a permanent field-based coalition dedicated to protecting and growing the federal investment in national service. City Year serves as the organizational and operational host of Voices for National Service and the coalition’s work is guided by a Steering Committee of CEOs of service organizations and leaders of state service commissions. The work of Voices for National Service is made possible through membership dues, philanthropic grants and gifts, and annual support from co- chairs and members of Voices for National Service’s Business Council and Champions Circle. Voices for National -

Former Seattle Mayor Norm Rice Joins Casey Family Programs’ Board of Trustees

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE July 2, 2012 For more information Marty McOmber, 206-270-4907 [email protected] Former Seattle Mayor Norm Rice Joins Casey Family Programs’ Board of Trustees SEATTLE – The Board of Trustees of Casey Family Programs announced the appointment today of president and CEO of The Seattle Foundation Norman B. Rice as the newest trustee of its 7-member board. Rice joins Casey Family Programs with more than two decades of executive leadership in public, private and philanthropic organizations. He will remain president and CEO of The Seattle Foundation, one of the nation’s largest community foundations. Rice is also the former mayor of Seattle. “The members of the Board of Trustees are very pleased to welcome Norm Rice to Casey Family Programs,” said Shelia Evans-Tranumn, chair of the Board of Trustees. “His depth of knowledge and broad array of experience will make him a valuable asset to the foundation as we continue building supportive communities so all children may grow up in safe, stable and permanent families.” Headquartered in Seattle, Casey Family Programs is the nation’s largest operating foundation whose work is focused on safely reducing the need for foster care and building communities of hope for all of America’s children and families. Casey Family Programs works in partnership with child welfare systems, families and communities across the United States to prevent child abuse and neglect and to find safe, permanent and loving families for all children. Established by Jim Casey, founder of United Parcel Service, the foundation will invest $1 billion by 2020 to safely reduce the number of children in foster care 50 percent. -

Context Statement

CONTEXT STATEMENT THE CENTRAL WATERFRONT PREPARED FOR: THE HISTORIC PRESERVATION PROGRAM DEPARTMENT OF NEIGHBORHOODS, CITY OF SEATTLE November 2006 THOMAS STREET HISTORY SERVICES 705 EAST THOMAS STREET, #204 SEATTLE, WA 98102 2 Central Waterfront and Environs - Historic Survey & Inventory - Context Statement - November 2006 –Update 1/2/07 THE CENTRAL WATERFRONT CONTEXT STATEMENT for THE 2006 SURVEY AND INVENTORY Central Waterfront Neighborhood Boundaries and Definitions For this study, the Central Waterfront neighborhood covers the waterfront from Battery Street to Columbia Street, and in the east-west direction, from the waterfront to the west side of First Avenue. In addition, it covers a northern area from Battery Street to Broad Street, and in the east- west direction, from Elliott Bay to the west side of Elliott Avenue. In contrast, in many studies, the Central Waterfront refers only to the actual waterfront, usually from around Clay Street to roughly Pier 48 and only extends to the east side of Alaskan Way. This study therefore includes the western edge of Belltown and the corresponding western edge of Downtown. Since it is already an historic district, the Pike Place Market Historic District was not specifically surveyed. Although Alaskan Way and the present shoreline were only built up beginning in the 1890s, the waterfront’s earliest inhabitants, the Native Americans, have long been familiar with this area, the original shoreline and its vicinity. Native Peoples There had been Duwamish encampments along or near Elliott Bay, long before the arrival of the Pioneers in the early 1850s. In fact, the name “Duwamish” is derived from that people’s original name for themselves, “duwAHBSH,” which means “inside people,” and referred to the protected location of their settlements inside the waters of Elliott Bay.1 The cultural traditions of the Duwamish and other coastal Salish tribes were based on reverence for the natural elements and on the change of seasons. -

2018 Gplex Seattle

2018 GPLEX SEATTLE Agenda 1 CONNECTING THE CITY OF BROTHERLY LOVE TO THE EMERALD CITY American Airlines is proud to support the Greater Philadelphia Leadership Exchange. 2 2018 GPLEX SEATTLE CONTENTS 4 WELCOME TO THE 2018 LEADERSHIP EXCHANGE 5 AGENDA 8 REGIONAL EXPLORATIONS 10 SPONSORS 12 ABOUT GREATER SEATTLE 14 By the Numbers 18 A Brief History 20 Population 22 Economy 24 Governance 26 Glossary of Seattle Terms 28 PLENARY SPEAKERS 44 LEADERSHIP DELEGATION 60 ABOUT THE ECONOMY LEAGUE 61 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS 62 BOARD OF DIRECTORS 64 ESSENTIAL INFORMATION Agenda 3 WELCOME TO THE 2018 LEADERSHIP EXCHANGE I’m excited to be taking part in my fourth GPLEX—and my first as executive director! I was a GPLEX groupie long before I ever imagined I’d be leading this great organization. In any case, I am thrilled to spend a few days with all of you, the movers and shakers who make Greater Philadelphia, well, great. You are among the most diverse cohort we’ve assembled, across both social identity and sector. In GPLEX’s 13th year, we’re incredibly proud to count an alumni base of nearly 1,000 leaders. Stand tall GPLEXers! As always, the board and staff of the Economy League were very deliberate in choosing this year’s destination; we always seek regions that share similarities to our own in size, economy, etc. That said, Seattle is certainly different from Philadelphia. In 1860, while Philadelphia was one of the world’s largest and most economically vibrant cities, the “workshop of the world,” Seattle’s population was about 200 souls; 100 years later, Philadelphia hit its population peak of two million and then saw 50 years of population decline before the slow and steady growth of the late 1990s to the present. -

Key Award – Irwin & Ferreiro

June 28, 2021 Press Release Contact: George Erb, coalition secretary, [email protected] Juli Bunting, coalition executive director, [email protected] WCOG recognizes Stacy Irwin and Kim Ferreiro for their professionalism and courage SEATTLE – The Washington Coalition for Open Government (WCOG) has presented Key Awards to Stacy Irwin and Kim Ferreiro for their professionalism and courage while working as public records officers in the Office of the Mayor of Seattle. The coalition, which is independent and nonpartisan, presents Key Awards throughout the year to people and organizations that do something notable for the cause of open government. With Ferreiro’s assistance, Irwin filed a whistleblower complaint regarding the handling of public records requests for text messages of Seattle Mayor Jenny Durkan. The complaint led to an ethics investigation that found the Mayor’s Office mishandled various requests after discovering the mayor’s text messages were missing for a period of about 10 months. The investigation found that Michelle Chen, the mayor’s legal counsel, violated the state Public Records Act when she decided to exclude Durkan’s missing texts from certain requests. The report said Chen departed from best practices when she decided the Mayor’s Office wouldn’t inform requesters that Durkan’s texts from Aug. 28, 2019, to June 25, 2020, had not been retained. The report said Irwin and Ferreiro objected to many of Chen’s decisions and to how Chen had directed them to process various requests. “The records reviewed during this investigation show that Irwin and Ferreiro were knowledgeable public records officers who strived to follow best practices when responding to PRA requests,” it said. -

FB Guide 2021.Indd

MMontanaontana StateState BBobcatsobcats 22021021 BBigig SSkyky KKickoffickoff JJulyuly 225-265-26 SSpokane,pokane, WashingtonWashington MMontanaontana StateState One of only 69 colleges and universities (out of more than 5,300) rated by The Carnegie Foundation that maintain “very high research activities” and a “signifi cant commitment to community engagement” MSU leads the nation in Goldwater Scholars In 2018-19 MSU students earned Goldwater Scholarships, a Rhodes Scholarship, a Marshall Scholarship, a Udall Scholarship, and a Newman Civic Fellowship MSU is Montana’s largest university (16,850 in 2019-20), its largest research university, and the state’s largest research and development entity of any kind BBobcatobcat FootballFootball The only school to win National Championship at three diff erent levels (NAIA-1956, NCAA Division II-1976, NCAA I-AA/FCS-1984 23 conference championships 6 Super Bowl players, 18 NFL players, 13 CFL players 1 NFL Hall of Famer (Jan Stenerud, the only Big Sky player in the Pro Football Hall of Fame), 2 CFL Hall of Famers 2 CFL Most Outstanding Players in the last decade 22021021 BBobcatobcat FFootballootball QQuickuick FFactsacts MONTANA STATE UNIVERSITY Name (Founded) ................Montana State University (1893) Location .......................................................... Bozeman, MT Enrollment ................................................................... 16,600 President ..................................................Dr. Waded Cruzado Athletic Director ..............................................Leon -

Historic Seattle

Historic seattle 2 0 1 2 p r o g r a m s WHat’s inside: elcome to eattle s premier educational program for learning W s ’ 3 from historic lovers of buildings and Heritage. sites open to Each year, Pacific Northwest residents enjoy our popular lectures, 4 view tour fairs, private home and out-of-town tours, and special events that foster an understanding and appreciation of the rich and varied built preserving 4 your old environment that we seek to preserve and protect with your help! house local tours 5 2012 programs at a glance January June out-of-town 23 Learning from Historic Sites 7 Preserving Utility Earthwise Salvage 5 tour Neptune Theatre 28 Special Event Design Arts Washington Hall Festive Partners’ Night Welcome to the Future design arts 5 Seattle Social and Cultural Context in ‘62 6 February 12 Northwest Architects of the Seattle World’s Fair 9 Preserving Utility 19 Modern Building Technology National Archives and Record Administration preserving (NARA) July utility 19 Local Tour 10 Preserving Utility First Hill Neighborhood 25 Interior Storm Windows Pioneer Building 21 Learning from Historic Sites March Tukwila Historical Society special Design Arts 11 events Arts & Crafts Ceramics August 27 Rookwood Arts & Crafts Tiles: 11 Open to View From Cincinnati to Seattle Hofius Residence 28 An Appreciation for California Ceramic Tile Heritage 16 Local Tour First Hill Neighborhood April 14 Preserving Your Old House September Building Renovation Fair 15 Design Arts Cover l to r, top to bottom: Stained Glass in Seattle Justinian and Theodora, -

Candidate Name

KING COUNTY DEMOCRATS 2012 CANDIDATE QUESTIONNAIRE – CONGRESS, SENATE, LEGISLATURE Candidate Name Stephanie Bowman Position sought State House of Representatives Residence Legislative, 11, 8, 7 County Council and Congressional district Do you publicly YES declare to be a Democrat? Campaign Information Campaign Name People for Stephanie Bowman Web page Campaign Email [email protected] address Manager Campaign mailing PO Box 84415, Seattle WA 98124 address Campaign phone 206-898-3043 number Campaign FAX Campaign Christian Sinderman Consultant(s) Candidate Background: Community service, education, employment and other relevant experience. Describe your qualifications, education, employment, community and civic activity, Union affiliation and other relevant experience. I will bring to the Legislature more than fifteen years of public policy experience in the non-profit, public and private sector, community leadership and personal experiences as a single, professional female from a working-class background who understands the struggles of the middle class. In my job as the Executive Director of the statewide non-profit Washington Asset Building Coalition (WABC), I work every day on progressive state policies and programs to help Washington families build an economic safety net: investing in education, build savings and creating opportunities to own a home or start a business. Specifically, issues on which we work are foreclosure prevention; providing access to safe financial services (i.e., helping un-banked residents and eliminating practices such as predatory lending); Working Families Tax Credit and EITC campaigns, and microenterprise development, particularly for women and minority populations. The opportunity to build these sorts of assets not only helps citizens move out of poverty but is fundamental to maintaining and growing the middle class. -

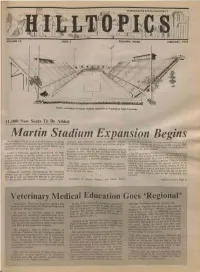

Martin Stadium Expansion Begins Work Began January 18On a Two-Part Project to Enlarge (Services and Materials) Valued at $664.000

VOLUME 10 ISSUE 2 PULLMAN, WASH. FEBRUARY, 1979 Artist's conception of Martin Stadium expansion at Washington State University. -11,000 New Seats To Be Added Martin Stadium Expansion Begins Work began January 18on a two-part project to enlarge (services and materials) valued at $664.000. Another membership in the Pac-10 Conference and Division IA of Martin Stadium at Washington State University by 11.000 $412.000is expected from a variety of activities and gifts. the NCAA. Without the increased seating capacity, WSU seats and construct a new track and field facility on a would have been forced to play "home" football games in five-acre site near the WSU Golf Course. Lloyd W. Peterson. senior assistant attorney general Spokane's Joe Albi Stadium. assigned to WSU. said he was satisfied with the legal Under a resolution approved unanimously by WSU document covering the project. Five days earlier he was The NCAA requires Division LAteams provide football regents meeting in special session a day earlier. the reluctant to assure university regents that they were' stadiums with at least 30,000seats. Martrn Sta~Hum now Cougar Club Foundation will undertake the project at an legally protected by a previous document. accommodates 27.000.More than 10,000seats Will be add- estimated cost of $2.274.000.The project is expected to be ed in the expansion currently underwar. Plans call for the completed early next fall. At that time, the Cougar Club The WSU' Athletic Department expects to genera, runnmg track surrounding the playing surface to be Foundation. a group of WSU athletic. -

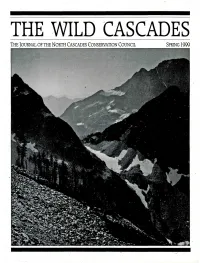

Spring-1999.Pdf

THE WILD CASCADES THE JOURNAL OF THE NORTH CASCADES CONSERVATION COUNCIL SPRING 1999 he North Cascades Conservation TCouncil was formed in 1957 "To pro tect and preserve the North Cascades' scenic, scientific, recreational, educa THE WILD CASCADES Spring 1999 tional, and wilderness values." Continu ing this mission, NCCC keeps govern ment officials, environmental organiza tions, and the general public informed In This Issue about issues affecting the Greater North Cascades Ecosystem. Action is pursued 3 The President's Report — MARC BARDSLEY through legislative, legal, and public par ticipation channels to protect the lands, 4 Mad River: Motorcycle Romper Room? Or Addition to waters, plants and wildlife. Glacier Peak Wilderness? — HARVEY MANNING Over the past third of a century the NCCC has led or participated in cam 6 Hot Flashes from Other Fronts paigns to create the North Cascades Na tional Park Complex, Glacier Peak Wil 8 Bad News for the Beckler — RICK MCGUIRE derness, and other units of the National Wilderness System from the WO. Dou Decision Time Nears for Middle Fork Snoqualmie glas Wilderness north to the Alpine Lakes — RICKMCGUIRE Wilderness, the Henry M. Jackson Wil derness, the Chelan-Sawtooth Wilderness 9 The Northern Pacific Land Grant — Revest It Now? and others. Among its most dramatic vic Let's Be Practical: The Pragmatic Crusade — RICK MCGUIRE tories has been working with British Co lumbia allies to block the raising of Ross Volleys and Thunders — HARVEY MANNING Dam, which would have drowned Big The Railroad Land Grants Are Not History — GEORGE DRAFRAN Beaver Valley. REVIEWS BY HARVEY MANNING 13 New Books of Some Note — MEMBERSHIP North Cascades Crest: Notes and Images from America's Alps, JAMES The NCCC is supported by member MARTIN; Geology of the North Cascades, ROWLAND TABOR AND RALPH dues and private donations.