Lean Thinking in Emergency Departments: a Critical Review

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Midnight Special Songlist

west coast music Midnight Special Please find attached the Midnight Special song list for your review. SPECIAL DANCES for Weddings: Please note that we will need your special dance requests, (I.E. First Dance, Father/Daughter Dance, Mother/Son Dance etc) FOUR WEEKS in advance prior to your event so that we can confirm that the band will be able to perform the song(s) and that we are able to locate sheet music. In some cases where sheet music is not available or an arrangement for the full band is need- ed, this gives us the time needed to properly prepare the music and learn the material. Clients are not obligated to send in a list of general song requests. Many of our clients ask that the band just react to whatever their guests are responding to on the dance floor. Our clients that do provide us with song requests do so in varying degrees. Most clients give us a handful of songs they want played and avoided. Recently, we’ve noticed in increase in cli- ents customizing what the band plays and doesn’t play with very specific detail. If you de- sire the highest degree of control (allowing the band to only play within the margin of songs requested), we ask for a minimum of 100 requests. We want you to keep in mind that the band is quite good at reading the room and choosing songs that best connect with your guests. The more specific/selective you are, know that there is greater chance of losing certain song medleys, mashups, or newly released material the band has. -

Hatching Dance Hits

of the Hot Dance Songs chart. “Now we’re in uencing the industry, putting out songs everyone copies.” And with apparent ease. “Closer” co- “We plucked writer Shaun Frank says that in November ourselves from obscurity and 2015, after Taggart made the beat in a then started 30-minute session with Freddy Kennett of delivering Louis the Child, they did the rest on a tour smashes,” says Taggart bus in an hour, peppering in lines about left, onstage Taggart’s experience hooking up with an ex, with Pall in in then “realizing he actually still hates her,” Portland, Ore. as Frank explains. “He wanted to nish the song, and I was like, ‘So why don’t you just sing it?’ Drew’s like, ‘No way, I’ve never management to conrm a session (so did hacking the system? Cinderellas? sung.’ But we set up a mic in the bus, cut it, Dua Lipa); and Weezer circled back after Svengalis? They tag-team another zinger: and that’s the vocal we used.” refusing a cameo in The Chainsmokers’ “It’s like if LMFAO just started making...” The New York native duo oers 2016 Coachella set. says Pall, and Taggart nishes: “...the illest something simultaneously fresh and “They were like, ‘Yo! We should do a track shit and stopped dressing like idiots.” familiar to contemporary dance-pop together,’ and I’m like, ‘Oh, really?’ ” says crossover. The pair isn’t linked to a trendy Pall. “I can’t blame somebody for saying no HE CHAINSMOKERS ARE sound like trop-house. The songs are early on, but it depends on how you said no omnivorous music nerds. -

Major Lazer Essential Mix Free Download

Major lazer essential mix free download Stream Diplo & Switch aka Major Lazer - Essential Mix - July by A.M.B.O. from desktop or your mobile device. Stream Major Lazer [Switch & Diplo] - Essential Mix by A Ketch from desktop or your Krafty Kuts - Red Bull Thre3style Podcast (Free Download). Download major-lazer- essential-mix free mp3, listen and download free mp3 songs, major-lazer-essential-mix song download. Convert Youtube Major Lazer Essential Mix to MP3 instantly. Listen to Major Lazer - Diplo & Friends by Core News Join free & follow Core News Uploads to be the first to hear it. Join & Download the set here: Diplo & Friends Diplo in the mix!added 2d ago. Free download Major Lazer Essential Mix mp3 for free. Major Lazer on Diplo and Friends on BBC 1Xtra (01 12 ) [FULL MIX DOWNLOAD]. Duration: Grab your free download of Major Lazer Essential Mix by CRUCAST on Hypeddit. Diplo FriendsFlux Pavillion one Hour Mix on BBC Radio free 3 Essential Mix - Switch & Diplo (aka Major Lazer) Essential MixSwitch. DJ Snake has put up his awesome 2 hour Essential Mix up for free You can stream DJ Snake's Essential Mix below and grab that free download so you can . Major Lazer, Travis Scott, Camila Cabello, Quavo, SLANDER. Essential Mix:: Major Lazer:: & Scanner by Scanner Publication date Topics Essential Mix. DOWNLOAD FULL MIX HERE: ?showtopic= Essential Mix. Track List: Diplo Mix: Shut Up And Dance 'Ravin I'm Ravin' Barrington Levy 'Reggae Music Dub. No Comments. See Tracklist & Download the Mix! Diplo and Switch (original Major Lazer) – BBC Essential Mix – Posted in: , BBC Essential. -

Just the Right Song at Just the Right Time Music Ideas for Your Celebration Chart Toppin

JUST THE RIGHT SONG AT CHART TOPPIN‟ 1, 2 Step ....................................................................... Ciara JUST THE RIGHT TIME 24K Magic ........................................................... Bruno Mars You know that the music at your party will have a Baby ................................................................ Justin Bieber tremendous impact on the success of your event. We Bad Romance ..................................................... Lady Gaga know that it is so much more than just playing the Bang Bang ............................................................... Jessie J right songs. It‟s playing the right songs at the right Blurred Lines .................................................... Robin Thicke time. That skill will take a party from good to great Break Your Heart .................................. Taio Cruz & Ludacris every single time. That‟s what we want for you and Cake By The Ocean ................................................... DNCE California Girls ..................................................... Katie Perry your once in a lifetime celebration. Call Me Maybe .......................................... Carly Rae Jepson Can‟t Feel My Face .......................................... The Weeknd We succeed in this by taking the time to get to know Can‟t Stop The Feeling! ............................. Justin Timberlake you and your musical tastes. By the time your big day Cheap Thrills ................................................ Sia & Sean Paul arrives, we will completely -

Playlist in 1969, Yale University Admitted Its First Women Undergraduates, Thus Ending 268 Years As an All-Male College

YALE NEEDS WOMEN Playlist In 1969, Yale University admitted its first women undergraduates, thus ending 268 years as an all-male college. Yale Needs Women (Sourcebooks, 2019) tells their story. Here is the playlist to go with it: 22 songs released between 1969 and 1972, plus a two-song prelude from 1967. A quick scan will show that male performers outnumber women on this playlist, perhaps an odd choice given the Yale Needs Women title. It’s a reflection of the times, however. The music industry needed women too. You can find this playlist on Spotify. Search anne.g.perkins, or use this link: https://open.spotify.com/playlist/4aXLc1veNkKCMqCWd0biKE To find out more about Yale Needs Women and the first women undergraduates at Yale, go to yaleneedswomen.com. Many thanks to Rick High, Lily and Mac Perkins-High, and David and Ginger Kendall for their help in creating this playlist. Sources for the liner notes below are at the end. PRELUDE: 1967 1. Aretha Franklin, RESPECT. Aretha Franklin was the first woman ever inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame, and “Respect” was her first song to hit #1. She was twenty-five years old, six years into an abusive marriage that she would end in 1969, a black woman in a nation where that status meant double discrimination. “All I’m askin’ is for a little respect.” 2. Country Joe and The Fish, I-FEEL-LIKE-I’M-FIXIN’-TO-DIE RAG. Released in November 1967, the I-Feel-Like-I’m-Fixin’-To-Die Rag became one of the country’s most popular Vietnam War protest songs, particularly after its performance at Woodstock in August 1969. -

What Did You Learn in School Today? How Ideas Mattered for Policy Changes in Danish and Swedish Schools 1990-2011

What did you learn in school today? How ideas mattered for policy changes in Danish and Swedish schools 1990-2011 Line Renate Gustafsson PhD Dissertation What did you learn in school today? How ideas mattered for policy changes in Danish and Swedish schools 1990-2011 Politica © Forlaget Politica and the author 2012 ISBN: 978-87-7335-162-8 Cover: Svend Siune Print: Juridisk Instituts Trykkeri, Aarhus Universitet Layout: Annette B. Andersen Submitted 13 January 2012 The public defense takes place 25 May 2012 Published May 2012 Forlaget Politica c/o Department of Political Science and Government Aarhus University Bartholins Allé 7 DK-8000 Aarhus C Denmark Table of content Translations and abbreviations .......................................................................................................................... 15 Acknowledgements ..................................................................................................................................................... 19 Chapter 1: Introduction .............................................................................................................................................. 23 1.1 Empirical puzzle .......................................................................................................................... 23 1.2 The research question: How did ideas change? .................................................... 24 1.3 The argument in brief ............................................................................................................. -

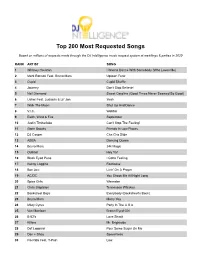

Most Requested Songs of 2020

Top 200 Most Requested Songs Based on millions of requests made through the DJ Intelligence music request system at weddings & parties in 2020 RANK ARTIST SONG 1 Whitney Houston I Wanna Dance With Somebody (Who Loves Me) 2 Mark Ronson Feat. Bruno Mars Uptown Funk 3 Cupid Cupid Shuffle 4 Journey Don't Stop Believin' 5 Neil Diamond Sweet Caroline (Good Times Never Seemed So Good) 6 Usher Feat. Ludacris & Lil' Jon Yeah 7 Walk The Moon Shut Up And Dance 8 V.I.C. Wobble 9 Earth, Wind & Fire September 10 Justin Timberlake Can't Stop The Feeling! 11 Garth Brooks Friends In Low Places 12 DJ Casper Cha Cha Slide 13 ABBA Dancing Queen 14 Bruno Mars 24k Magic 15 Outkast Hey Ya! 16 Black Eyed Peas I Gotta Feeling 17 Kenny Loggins Footloose 18 Bon Jovi Livin' On A Prayer 19 AC/DC You Shook Me All Night Long 20 Spice Girls Wannabe 21 Chris Stapleton Tennessee Whiskey 22 Backstreet Boys Everybody (Backstreet's Back) 23 Bruno Mars Marry You 24 Miley Cyrus Party In The U.S.A. 25 Van Morrison Brown Eyed Girl 26 B-52's Love Shack 27 Killers Mr. Brightside 28 Def Leppard Pour Some Sugar On Me 29 Dan + Shay Speechless 30 Flo Rida Feat. T-Pain Low 31 Sir Mix-A-Lot Baby Got Back 32 Montell Jordan This Is How We Do It 33 Isley Brothers Shout 34 Ed Sheeran Thinking Out Loud 35 Luke Combs Beautiful Crazy 36 Ed Sheeran Perfect 37 Nelly Hot In Herre 38 Marvin Gaye & Tammi Terrell Ain't No Mountain High Enough 39 Taylor Swift Shake It Off 40 'N Sync Bye Bye Bye 41 Lil Nas X Feat. -

The Top 7000+ Pop Songs of All-Time 1900-2017

The Top 7000+ Pop Songs of All-Time 1900-2017 Researched, compiled, and calculated by Lance Mangham Contents • Sources • The Top 100 of All-Time • The Top 100 of Each Year (2017-1956) • The Top 50 of 1955 • The Top 40 of 1954 • The Top 20 of Each Year (1953-1930) • The Top 10 of Each Year (1929-1900) SOURCES FOR YEARLY RANKINGS iHeart Radio Top 50 2018 AT 40 (Vince revision) 1989-1970 Billboard AC 2018 Record World/Music Vendor Billboard Adult Pop Songs 2018 (Barry Kowal) 1981-1955 AT 40 (Barry Kowal) 2018-2009 WABC 1981-1961 Hits 1 2018-2017 Randy Price (Billboard/Cashbox) 1979-1970 Billboard Pop Songs 2018-2008 Ranking the 70s 1979-1970 Billboard Radio Songs 2018-2006 Record World 1979-1970 Mediabase Hot AC 2018-2006 Billboard Top 40 (Barry Kowal) 1969-1955 Mediabase AC 2018-2006 Ranking the 60s 1969-1960 Pop Radio Top 20 HAC 2018-2005 Great American Songbook 1969-1968, Mediabase Top 40 2018-2000 1961-1940 American Top 40 2018-1998 The Elvis Era 1963-1956 Rock On The Net 2018-1980 Gilbert & Theroux 1963-1956 Pop Radio Top 20 2018-1941 Hit Parade 1955-1954 Mediabase Powerplay 2017-2016 Billboard Disc Jockey 1953-1950, Apple Top Selling Songs 2017-2016 1948-1947 Mediabase Big Picture 2017-2015 Billboard Jukebox 1953-1949 Radio & Records (Barry Kowal) 2008-1974 Billboard Sales 1953-1946 TSort 2008-1900 Cashbox (Barry Kowal) 1953-1945 Radio & Records CHR/T40/Pop 2007-2001, Hit Parade (Barry Kowal) 1953-1935 1995-1974 Billboard Disc Jockey (BK) 1949, Radio & Records Hot AC 2005-1996 1946-1945 Radio & Records AC 2005-1996 Billboard Jukebox -

Using Popular Song Lyrics to Teach Character and Peace Education

California State University, San Bernardino CSUSB ScholarWorks Theses Digitization Project John M. Pfau Library 2007 Using popular song lyrics to teach character and peace education Stacy Shayne Corbett Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.lib.csusb.edu/etd-project Part of the Humane Education Commons, Music Commons, and the Peace and Conflict Studies Commons Recommended Citation Corbett, Stacy Shayne, "Using popular song lyrics to teach character and peace education" (2007). Theses Digitization Project. 3246. https://scholarworks.lib.csusb.edu/etd-project/3246 This Project is brought to you for free and open access by the John M. Pfau Library at CSUSB ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses Digitization Project by an authorized administrator of CSUSB ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. USING POPULAR SONG LYRICS TO TEACH CHARACTER AND PEACE EDUCATION A Project Presented to the Faculty of California State University, San Bernardino In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts in Education: Holistic and Integrative Education by Stacy Shayne Corbett March 2007 USING POPULAR SONG LYRICS TO TEACH CHARACTER AND PEACE EDUCATION A Project Presented to the Faculty of California State University, San Bernardino by Stacy Shayne Corbett March 2007 Approved by: Dr. Robert London, First Reader ____ Dr. Samuel Crowell,'Second Reader © 2007 Stacy Shayne Corbett ABSTRACT With an increasing emphasis on standardized test scores and more and more exposure to adult issues and violence, there is a growing need for peace education. As an adult, I have discovered the profound messages songwriters can convey to their audience. -

First Headliner Announced for Reading & Leeds Festival 2017 – a Uk Festival Exclusive

EMBARGOED UNTIL 7:45AM THURSDAY 1 DECEMBER 2016 PRESENTS 25TH – 27TH AUGUST 2017, BANK HOLIDAY WEEKEND FIRST HEADLINER ANNOUNCED FOR READING & LEEDS FESTIVAL 2017 – A UK FESTIVAL EXCLUSIVE MUSE MAJOR LAZER, BASTILLE, ARCHITECTS, TORY LANEZ, AT THE DRIVE-IN, GLASS ANIMALS, AGAINST THE CURRENT, ANDY C, DANNY BROWN AND WHILE SHE SLEEPS ALSO CONFIRMED HUNDREDS MORE TO BE ANNOUNCED FOR 2017 http://www.readingandleedsfestival.com Reading & Leeds Festivals announce Muse, in a UK festival exclusive, as the first headliners for next year’s festival, taking place 25-27 August 2017. Stadium rock royalty, Muse are one of the most influential and revered live bands of modern times. Led by the commanding presence of frontman Matt Bellamy, the trio have taken to the biggest stages around the world with their interstellar anthems for over 22 years, and their return to Reading & Leeds promises to be yet another landmark moment in their storied career. Muse commented: "We’re very excited to be playing Reading and Leeds again. More news about our plans for 2017 coming in the new year." Melvin Benn commented: “I’m thrilled to be able to announce Muse as the first headliner for Reading and Leeds 2017. Their incredible live show promises to be an unforgettable performance - we have so much more to announce and I can’t wait to reveal the rest of the line up.” Also confirmed for Reading & Leeds 2017 in a UK festival exclusive, are dancehall-rejuvenators Major Lazer. Diplo, Jillionaire and Walshy Fire have become the soundtrack of modern dance, claiming No.1 records, chart-dominating tracks such as ‘Lean On’ and ‘Cold Water’ as well as live shows packed with genre-mashing moments promising an unrivalled party atmosphere. -

Lean on Me AZ: Strengthening Families to Prevent Child Adversity

Lean On Me AZ: Strengthening Families to Prevent Child Adversity Written and developed by Jennifer Dokes, JDD Specialties LLC, and Claire Louge, Prevent Child Abuse Arizona April 2021 Introduction The Covid-19 pandemic’s disruptions to everyday life — lockdowns, virtual schooling, social distancing, economic instability, uncertainty — caused many to worry about the well-being of children and families. Strong families are the building blocks of the flourishing communities we want to live in. When our community’s families are overwhelmed by multiple or persistent stressors - including the ones emerging or exacerbated by the pandemic – this may compromise their ability to provide the stable, safe, and nurturing environments children need to thrive. All parents and caregivers will need help at some point. Empowering families is the key to protecting children from abuse and neglect so that they never happen in the first place. Prevention succeeds when the community is there for parents at the moment that they need information, support, or help dealing with overwhelming stress. Opportunities to offer this support present themselves every day. In this Lean On Me AZ report and toolkit, you will find things you can do to seize those opportunities. Lean On Me AZ is an effort to raise awareness about the factors that protect families from overwhelming stress, and provide tools to help community members strengthen families. This effort grew from a popular perception at the beginning of the pandemic that protocols to mitigate community spread were affecting child well-being. Questions at the forefront of conversations in the media, the public sector, and the human service sector had a similar vein: How could we continue to identify and report child abuse, if the kids were hidden from public view? Good question. -

MAJOR LAZER “We're Not Making the World Smaller,”

MAJOR LAZER “We’re not making the world smaller,” says Walshy Fire, one-third of the global hitmaking behemoth that is Major Lazer. “We’re making the party bigger.” For Major Lazer, which also includes Diplo and Jillionaire, that is a noble mission, and the trio bring a sophisticated fusion of Caribbean and American music—Trinidadian soca, Jamaican reggae, American hip-hop and dance music—to dance floors across the world. Over the last ten years the group has expanded from a notoriously raucous side project into the biggest musical act in the world, crafting multiplatinum hits like “Cold Water” (featuring Justin Bieber and Danish singer-songwriter MØ) and “Run Up” (with Nicki Minaj and PARTYNEXTDOOR). With a combustible vocal turn by MØ and sharp beats by French producer DJ Snake, their ferocious 2015 single “Lean On” broke records for independent songs on pop radio to become one of the most popular songs of the 2010s: an era- defining smash around the world. That mind-boggling success has not distracted the trio from their goal of making innovative music for the entire planet. “We create this Carnival atmosphere for people, like a Caribbean party where you’re dancing in the streets,” says Diplo. “That’s the vibe we’re trying to create, the language we’re trying to write. It doesn’t sound like anything else, because no one has done this kind of fusion before. Because of that, we don’t have a roadmap. We don’t always know if we’re doing it right, but we’re going to keep doing it.” By all accounts, the musicians who make up Major Lazer are doing it exactly right.