Driving the Change from Computers to Computerisation

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

M.Tech Admission 2021-22 Department of Materials Science & Metallurgical Engineering

Apply online at www.iith.ac.in M.Tech Admission 2021-22 Department of Materials Science & Metallurgical Engineering Indian Institute of Technology Hyderabad Research Interests: Nanocrystalline materials, High entropy alloys, Bulk metallic glasses, Thermodynamics and kinetics of phase transformations, Transmission electron microscopy and atom probe MSME Faculty tomography Prof. B.S.Murty PhD: IISc Bangalore, India Contact: [email protected], +91 (40) 2301 6033 Research Interests: Research Interests: Design and development of novel high entropy alloys for Welding advanced structural applications Additive manufacturing Development of light metals alloys for novel applications Bulk nano- and heterostructured materials by severe plastic deformation processing Thermo-mechanical and other advance materials processing Crystallographic texture Mechanical behavior of materials Prof. Pinaki P. Bhattacharjee Prof. G.D. Janakiram PhD: IIT Kanpur, India PhD: IIT Madras, India Contact: [email protected], +91 (40) 2301 6069 Contact: [email protected], +91 (40) 2301 6565 Research Interests: Research Interests: Powder Metallurgy & Sintering Mechanisms, Metal Additive Advanced Multi-Functional Nanostructured Materials/High Manufacturing, Nanostructures, Entropy Alloys High Entropy Alloys, MAX Phases and MXene, Advanced Combinatorial Alloy Design of emerging materials (Co-Cu-Fe- ceramics & composites Ni-Zn High Entropy Alloys, CIGS & CZTSSe solar photovoltaics, High temperature materials, Biomaterials Additive Manufactured Binary -

Staff Profile | Dr.M.F.Valan, Dept. of Chemistry

M.F.VALAN Assistant Professor, Research Supervisor, Department of Chemistry, Loyola College, Scientist, LIFE (Loyola Institute of Frontier Energy) Nungambakkam, Chennai, Tamil Nadu, India, Pin: 600034 Ph. No: +91 9442061575 Email: [email protected] EMPLOYMENT HISTORY EDUCATION [email protected] September 2011 Ph.D. Chemistry Current Assistant Professor June 2013-Current (Pharmacognostical, Under Graduate, Post Graduate and Research Programmes Pharmcological and Loyola College, Nungabakkam, Chennai, Tamil Nadu, India Phytochemical Analysis of a few medicinal Plants in Assistant Professor Tirunelveli Hills), July 2010-May 2013 Manonmanium Sunderanar Bachelor of Engineering Programme, University, Tirunelveli, Loyola ICAM College of Engineering and Technology, Tamilnadu, India. Nungambakkam, Chennai. March, 2007 June 2009-June 2010 M.Phil. Chemistry Assistant Professor (Phytochemical Analysis) Bachelor of Engineering Programme , Manonmanium Sunderanar Sakthi College of Engineering and Technology, Chennai University, Thirunelveli, Tamilnadu, India. Assistant Professor October 2008-May 2009 April 2004 Bachelor of Engineering Programme, Pontifical Degree in Karpaga Vinayaga College of Engineering and Technology, Philosophy Nungambakkam, Chennai. De Nobili College, Jnana Deepa Vidhya Peeth, Pune, Maharashtra, India. Assistant Professor February 2004-September 2008 Under Graduate, and Post Graduate Programmes March 2002 M.Sc. Chemistry St.Xavier’s College, Palayamkottai, St. Joseph’s College, Tiruchy, Tirunelveli, Tamil Nadu, India Tamilnadu, India. April 2004-November 2008 March 2000 Assistant Director B.Sc. Chemistry Jesuit Madurai Province Prenovitiate, St. Joseph’s College, Tiruchy, Thanjavur, Tamil Nadu, India Tamilnadu, India. EXPERIENCE IN WRITING AND PUBLICATION LANGUAGE KNOWN ▪ Hindi Prathmic Level ▪ As a convener edited the Proceedings of State level Seminar ▪ German Lang. A1 Level ▪ Prepared study materials for M.Sc., B.Sc., B.E.,B.Tech Chemistry subjects ▪ Supervised M.Sc, Project and report writing for 18 students. -

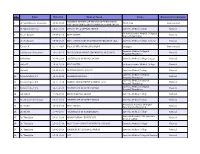

Awards and Recognitions

S.No Name Dated On Name of Award Venue National / International HONORED MEMBER OF THE HUB OF PRESTIGIOUS 1 Dr. Senthilkumar Sivanesan 03-04-2018 MSTF, Iran International MUSTAFA SCIENCE AND TECHNOLOGY FOUNDATION (MSTF) 2 Dr. Vijayalakshmi.S 25-02-2019 SPECIAL RECOGNITION AWARD Saveetha Medical College National Sri Ramachandra Medical College & 3 Dr. Archana. R 09-09-2018 BEST POSTER National Research Institution 4 Dr. Archana. R 05-03-2019 BEST COMMITTEE FOR SAVEETHA RESEARCH CELL Saveetha Medical College, Chennai National 5 Kannan R 02-11-2007 EXSA SILVER AWARD SINGAPORE Singapore International Saveetha Medical College & 6 Lal Devayani Vasudevan 18-11-2016 DR.CV.RAMAN AWARD FOR MEDICAL RESEARCH National Hospital, Thandalam 7 Sudarshan 07-04-2016 CERTIFICATE OF APPRECIATION Saveetha Medical College Chennai National 8 Shoba K 28-04-2019 BEST POSTER Sri Ramachandra Medical College National 9 Shoba K 25-02-2019 DISTINGUISHED FACULTY Saveetha Medical College National Saveetha Medical College & 10 Narasimhalu C R V 18-11-2014 RESEARCH ARTICLE National Hospital, Thandalam Saveetha Medical College & 11 Narasimhalu C R V 13-11-2018 ANNUAL DEPARTMENT RANKING 2018 National Hospital, Thandalam Saveetha Medical College & 12 Narasimhalu C R V 03-11-2017 CERTIFICATE OF APPRECIATION National Hospital, Thandalam 13 Rajendran 07-04-2016 SERVICE APPRECIATION Saveetha Medical College National 14 Dr. Abraham Sam Rajan 07-04-2016 CERTIFICATE OF APPRECIATION Saveetha Medical College National Meenakshi Academy Of Higher 15 Dr. Sridevi 13-12-2013 BEST POSTER National Education And Research 16 Dr. Sridevi 27-09-2017 CERTIFICATE OF ACHIEVEMENT Saveetha Medical College National Saveetha Research Cell, Saveetha 17 Dr. -

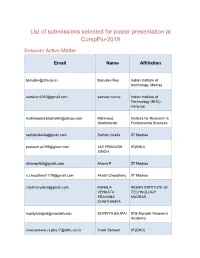

List of Submissions Selected for Poster Presentation at Compflu-2019

List of submissions selected for poster presentation at CompFlu-2019 Session: Active Matter Email Name Affiliation [email protected] Basudev Roy Indian Institute of technology, Madras [email protected] sameer kumar Indian Institute of Technology (BHU) Varanasi [email protected] Mahmoud Institute for Research in Sebtosheikh Fundamental Sciences [email protected] Sathish Akella IIT Madras [email protected] JAY PRAKASH IIT(BHU) SINGH [email protected] Ahana P IIT Madras [email protected] Akash Choudhary IIT Madras [email protected] KANALA INDIAN INSTITUTE OF VENKATA TECHNOLOGY SRAVANA MADRAS CHAITHANYA [email protected] SUPRIYA BAJPAI IITB-Monash Research Academy [email protected] Vivek Semwal IIT(BHU) [email protected] C Santhan Indian Institute of Technology Madras [email protected] Pratyush Dayal IIT Gandhinagar [email protected] Md Imaran IITB-Monash Research Academy [email protected] Prabha Chuphal Indian Institute of Science Education and Research Bhopal [email protected] Shambhavi Dikshit Indian Institute Of Technology (BHU), Varanasi [email protected] Suchismita Das IIT Bombay [email protected] Soudamini Sahoo Indian Institute of Science Education and Research, Bhopal [email protected] Karnika Singh Indian Institute of Technology Kanpur [email protected] Arabinda Bera Jawaharlal Nehru Centre for Advanced Scientific Research, Bengaluru-560064 [email protected] Prajitha M PhD scholar, IIT Madras [email protected] -

General Awareness

GENERAL AWARENESS January 2021 Vol. 9, Issue 05 A PUBLICATION OF GYANM EDUCATION & TRAINING INSTITUTE PVT. LTD. SCO 13-14-15, 2ND FLOOR, SEC 34-A, CHANDIGARH Contents NATIONAL NEWS CURRENT AFFAIRS NOVEMBER 03-39 October to November 2020 BULLET NEWS VIRTUAL SUMMIT HELD WITH LUXEMBOURG PM 40-66 June 2020 to Sept 2020 LATEST 100 GK MCQs 67-74 SBI PO PRELIMS 75-86 MODEL TEST PAPER Current GK Bytes 87-110 FIGURES TO REMEMBER REPO RATE 4.00% REVERSE REPO RATE 3.35% MARGINAL STANDING 4.25% FACILITY RATE BANK RATE 4.25% Prime Minister Narendra Modi and his Luxembourg counterpart Xavier Bettel STATUTORY LIQUIDITY RATIO 18.00% held a virtual summit on Nov 19. This was the first stand-alone Summit CASH RESERVE RATIO 3.00% meeting between India and Luxembourg in the past two decades. The two BASE RATE(s) 8.15 to leaders discussed the entire spectrum of bilateral relationship, including (of various banks) 9.40% strengthening of India-Luxembourg cooperation in the post-COVID world. Luxembourg is a small European country, surrounded by Belgium, Germany INDIA’s RANK IN and France. Global Hunger Index 2020 94th PM MODI ATTENDS 12TH BRICS SUMMIT th Teacher Status Index (GTSI) 6 Prime Minister Narendra Modi attended the 12th BRICS Summit on November Asia Power Index 2020 4th 17 in virtual mode. The summit was hosted by Russia, under the theme Global Global Economic Freedom Index 105th Stability, Shared Security and Innovative Growth. India will be taking over the Chairship of the BRICS for the year 2021 and will host the 13th BRICS Summit Human Capital Index 116th next year. -

About the Contributors

280 About the Contributors Raghu Santanam is an Associate Professor of Information Systems and Director of the MSIM Program in the W. P. Carey School of Business at Arizona State University. His current research focuses on consumer related issues in pricing of digital products, Health Information Technology, Business Process Change, and Cloud Computing. Dr. Santanam has helped a number of organizations on Information Systems and Business Process related changes. He serves as an Associate Editor for Information Systems Research, Decision Support Systems, Journal of the Association for Information Systems and Journal of Electronic Commerce Research. He is an advisory editor of the Elsevier series on “Handbooks in Information Systems.” He recently served as the Program Co-Chair for Workshop on E-Business, 2009. He facilitated the solutions and implementation work group proceedings in Arizona as part of the National Health Information Security and Privacy Collaboration project. Most recently, Dr. Santanam served as a co-PI on a research study entitled “Electronic Medical Records and Nurse Staffing: Best Practices and Performance Impacts.” This study examined the impact of EMR systems on hospital performance in California State. M. Sethumadhavan received his PhD (Number Theory) from Calicut Regional Engineering College (presently a National Institute of Technology). He is a Professor of Mathematics and Computer Science in Amrita Vishwa Vidyapeetham University, Coimbatore and is currently the Head, TIFAC CORE in Cyber Security. His area of interest is cryptography Mohit Virendra received his Ph.D. in Computer Science and Engineering from the State University of New York at Buffalo in 2008. He currently works in the Software Design and Development team at Brocade Communications Systems in San Jose, CA. -

Annual Report 2007 | Reports & Filings | Investors

Once upon a time, the world was spiky. Opportunities were unequal across countries, information was often walled and new economies were unheard of. But around the mid 990s, things started changing. Wealth began to spread, opening up fresh markets. A baby-boomer generation aged in developed countries while a Gen-Y exploded in emerging ones, rebalancing the workforce and propelling new economies. Technology became ubiquitous, connecting people and information. Together, these disruptive forces rearranged and leveled the global business-scape. Braving the waves of complex regulations and changing customer expectations, a new breed of entrepreneurs arrived to claim the unexplored land. They found a flat world. We live in exciting times. Infosys Annual Report 2006-07 | Winning in the Flat World Nandan M. Nilekani, CEO and Managing Director, Infosys Technologies Ltd., in conversation with Brianna Yvonne Dieter, Executive – Academic Relations, Infosys Technologies Ltd. Recently you have been talking about the world becoming companies should beat them by making their operations more flat. Could you elaborate further? cost-competitive and globally efficient. We believe that four major trends are changing the business Create customer loyalty through faster innovation: Customers stay landscape. They are: with companies which have the most innovative and useful products and services. Therefore, companies must be able to innovate rapidly The emergence of developing economies creating new markets l to offer products and services that customers value. In many cases, and accessible talent pools, this may require co-creating these offerings with customers or l A global shift in demographics, driving companies to tap young partners. and skilled talent pools outside of industrialized countries, Make money from information: Despite years of investment in l The ongoing adoption of technology which is changing how systems, few companies are truly able to leverage information to consumers and companies use technology, and improve their operational or financial performance. -

Iits, Iisc and Amrita Vishwa Vidyapeetham Among the 11 Universities in the Emerging Economies University Rankings 2020

IITs, IISc and Amrita Vishwa Vidyapeetham among the 11 universities in THE Emerging Economies University Rankings 2020 businessinsider.in/careers/news/iits-iisc-and-amrita-vishwa-vidyapeetham-among-the-11-universities-in-the- emerging-economies-university-rankings-2020/articleshow/74201891.cms Prerna SindwaniFeb 19, 2020, 09:39 IST The Times Higher Education (THE) released its latest rankings of institutions in emerging economies. China dominates the rankings this year with Tsinghua University, Peking University and Zhejiang University in the top three, but Saudi Arabia and South Africa have the highest average scores. Of the total 56 participating universities, the rankings feature 11 Indian universities in the top 100 — marking the highest representation since 2015. Times Higher Education (THE) has released its latest rankings of institutions in emerging economies. While China dominates the rankings this year with Tsinghua University, Peking University and Zhejiang University in the top three, Saudi Arabia and South Africa appears to be improving at a good pace with the highest average scores. 1/3 Of the total 56 participating universities, the rankings feature 11 Indian universities in the top 100 — marking its highest representation since 2015. This includes the premier Indian Institutes of Technology (IITs), Indian Institute of Science (IISc) and Institute of Chemical Technology (ICT). However, the surprise entrant was Coimbatore’s Amrita Vishwa Vidyapeetham, which also featured in the Eminence scheme of the Human Resource & Development ministry. It entered the top 100 for the very first time — crawling up 51 spots from last year. “There has long been a debate on the success of Indian universities in world rankings, and for too long they have been seen as underperforming on the global stage. -

Indian Institute of Technology Madras

26/08/2019 https://josaa.nic.in/seatinfo/root/InstProfile.aspx?instcd=110 Indian Institute of Technology Madras Type of the institute: Indian Institute of Technology Complete Mailing Address: IIT Madras P.O., Chennai 600036, INDIA Contact Person For Admission: Joint Registrar (Academic Courses) Designation: Joint Registrar Email: [email protected] Alternate Email: [email protected] Phone Nos: 91-44-22578035 Fax No: 91-44-22578042 Mobile No.: About the Institute: The Indian Institute of Technology Madras (IITM) is among the finest, globally reputed higher technological institutions that sensitive and constructively responsive to student expectations and national needs. IITM was founded in 1959 as an ‘Institute of National Importance’ by Government of India with technical and financial assistance from the Federal Republic of West Germany. IITM celebrated its Golden Jubilee in the year 2008-09. During these 50+ years, IIT Madras has gained reputation for the quality of its faculty and the outstanding caliber of the students in the undergraduate, postgraduate and research programmes. IITM is recognized as a centre of academic and research excellence offering engineering, science, management and humanities education on par with the best in the world. IITM is ranked as the #1 Technical Institutions in India in 2017, 2018 and 2019 by National Institutional Ranking Framework (www.nirf.gov.in). IITM campus is famous for its serene and scenic natural environment. Comprising 650 acres of lush green forest, including a large lake and a rich variety of flora and fauna, the campus is the pride of its residents and provides an ideal setting for serious academic and developmental pursuits. -

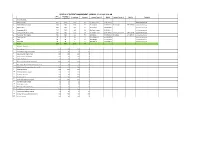

Status of Patient Management Chennai

STATUS OF PATIENT MANAGEMENT CHENNAI - 13.05.2021 8.00 AM Bed Covid bed Occupancy Vacancy Contact Person 1 Mobile Contact Person 2 Mobile Remarks Capacity availability I Covid Hospitals 1 MMC RGGGH 1618 1618 1527 91 Dr.Sudharshini 9791736334 O2 bed vacancy -0 2 Stanley Medical College 1400 1400 1348 52 Dr. Aravind 9840242328 Dr.Ramesh 9841736989 O2 bed vacancy -4 3 Kilpauk MCH 550 550 536 14 Dr. Geetha 9940087404 O2 bed vacancy -0 4 Omandurar MCH 727 727 695 32 Dr Pravin Kumar 8903306131 O2 bed vacancy -0 5 Govt Covid Hospital, Guindy 550 550 536 14 Dr. Mohankumar 9841744766 Dr Narayanaswami 9841170145 O2 bed vacancy -0 6 Tambaram TB Hospital 500 500 422 78 Dr Rathika 8939729493 Dr Sridhar 9444007311 O2 bed vacancy -0 7 Tambaram GH 45 45 42 3 Dr.C.Palanivel, 9444135154 O2 bed vacancy -3 8 KGH 50 50 36 14 Dr Karthiga 9444366296 O2 bed vacancy -4 9 KGH OMC 50 50 44 6 Dr.Kalpana 9345102848 O2 bed vacancy -0 Total 5490 5490 5186 304 B.Private Hospitals 1 Aakash Hospital 120 120 120 0 2 ACS Medical College And Hospital 100 100 63 37 3 Apollo Hospital, Greams Road 205 205 205 0 4 Apollo Hospitals, Vanagaram 123 123 123 0 5 Appasamy Hospital 87 87 87 0 6 Bhaarath medical college and hospital 160 160 160 0 7 Bharathiraja Hospital & Research Centre Pvt Ltd 93 93 93 0 8 Billroth Hospitals Shenoy Nagar, Chennai TN. 185 185 185 0 9 Chettinad Hospital 525 525 525 0 10 CSI Kalyani General Hospital 110 110 110 0 11 Dr. -

Annual Report 2019 - 2020

Year of 2 Million Surgeries PINNACLE OF EYE CARE ANNUAL REPORT 2019 - 2020 Registered Office Address: SANKARA EYE HOSPITAL 16A, Sankara Eye Hospital Street, Sathy Road, Sivanandapuram, Coimbatore - 641 035. Ph: 0422-2666450, 4236789. Email: [email protected] Www.sankaraeye.com It is the Divine Sankalpa of the Acharyas which has shaped our Institution over the past 43 years. Gurur Brahma Gurur Vishnu Gurur Devo Maheshwaraha: Gurur Saakshaat Parabrahma Tasmai Shri Guruvey Namaha: Our obeisance at the lotus feet of the Sankaracharyas of Kanchi 2 3 SANKARA EYE FOUNDATION INDIA SRI KANCHI KAMAKOTI MEDICAL TRUST Not-for-Profit healthcare organisation. One of the largest community eye care networks globally, with a Pan-India presence. Served over 10 million Rural patients so far Performed over 2 Million free eye surgeries 750 free eye surgeries every day VISION To work towards freedom from preventable and curable blindness. MISSION To provide unmatched eye care through a strong service oriented team. 4 5 SRI KANCHI KAMAKOTI SRI KANCHI KAMAKOTI MEDICAL TRUST MEDICAL TRUST STEERING COUNCIL MEMBERS BOARD OF TRUSTEES Mr. P. Jayendra Mr. S.G. Murali Mr. C.N. Srivatsan Mr. Sundar Radhakrishnan Dr. S. V. Balasubramaniam Dr. R. V. Ramani Dr. P. G. Viswanathan Chairman Founder & Managing Trustee Dr. P. Janakiraman Mr. Arun Madhavan Mr. Bhaskar Bhat SENIOR LEADERSHIP Dr. S. R. Rao Dr. S. Balasubramaniam Sri J. M. Chanrai Dr. Radha Ramani Dr. Jagadeesh Kumar Dr. P. Mahesh Co-Founder Reddy Shanmugam Group Head - Cataract & Group Head - Vitreo Retina Cornea Sri. Murali Krishnamurthy Sri. M. N. Padmanabhan Mrs. Seetha Chandrasekar Dr. Kaushik Murali Mr. -

ANNUAL REPORT 2019-20 IIT Bombay Annual Report 2019-20 Content

IIT BOMBAY ANNUAL REPORT 2019-20 IIT BOMBAY ANNUAL REPORT 2019-20 Content 1) Director’s Report 05 2) Academic Programmes 07 3) Research and Development Activities 09 4) Outreach Programmes 26 5) Faculty Achievements and Recognitions 27 6) Student Activities 31 7) Placement 55 8) Society For Innovation And Entrepreneurship 69 9) IIT Bombay Research Park Foundation 71 10) International Relations 73 11) Alumni And Corporate Relations 84 12) Institute Events 90 13) Facilities 99 a) Infrastructure Development b) Central Library c) Computer Centre d) Centre For Distance Engineering Education Programme 14) Departments/ Centres/ Schools and Interdisciplinary Groups 107 15) Publications 140 16) Organization 141 17) Summary of Accounts 152 Director's Report By Prof. Subhasis Chaudhuri, Director, IIT Bombay Indian Institute of Technology Bombay acknowledged for their research contributions. (IIT Bombay) has a rich tradition of pursuing We have also been able to further our links with excellence and has continually re-invented international and national peer universities, itself in terms of academic programmes and enabling us to enhance research and educational research infrastructure. Students are exposed programmes at the Institute. to challenging, research-based academics and IIT Bombay continues to make forays into a host of sport, cultural and organizational newer territories pertinent to undergraduate activities on its vibrant campus. The presence and postgraduate education. At postgraduate of world-class research facilities, vigorous level, a specially designed MA+PhD dual institute-industry collaborations, international degree programme in Philosophy under the exchange programmes, interdisciplinary HSS department has been introduced. IDC, the research collaborations and industrial training Industrial Design Centre, celebrated 50 years opportunities help the students of IIT Bombay to of its golden existence earlier this year.