Thinking with Music Angela Mcrobbie

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Download (2399Kb)

A Thesis Submitted for the Degree of PhD at the University of Warwick Permanent WRAP URL: http://wrap.warwick.ac.uk/ 84893 Copyright and reuse: This thesis is made available online and is protected by original copyright. Please scroll down to view the document itself. Please refer to the repository record for this item for information to help you to cite it. Our policy information is available from the repository home page. For more information, please contact the WRAP Team at: [email protected] warwick.ac.uk/lib-publications Culture is a Weapon: Popular Music, Protest and Opposition to Apartheid in Britain David Toulson A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in History University of Warwick Department of History January 2016 Table of Contents Acknowledgements………………………………………………………………...iv Declaration………………………………………………………………………….v Abstract…………………………………………………………………………….vi Introduction………………………………………………………………………..1 ‘A rock concert with a cause’……………………………………………………….1 Come Together……………………………………………………………………...7 Methodology………………………………………………………………………13 Research Questions and Structure…………………………………………………22 1)“Culture is a weapon that we can use against the apartheid regime”……...25 The Cultural Boycott and the Anti-Apartheid Movement…………………………25 ‘The Times They Are A Changing’………………………………………………..34 ‘Culture is a weapon of struggle’………………………………………………….47 Rock Against Racism……………………………………………………………...54 ‘We need less airy fairy freedom music and more action.’………………………..72 2) ‘The Myth -

Dennis Morris: Pil - First Issue to Metal Box 23 March - 15 May 2016 ICA Fox Reading Room

ICA For immediate release: 13 January 2016 Dennis Morris: PiL - First Issue to Metal Box 23 March - 15 May 2016 ICA Fox Reading Room Album cover image from PiL’s first album Public Image: First Issue (1978). © Dennis Morris – all rights reserved. The ICA presents rarely seen photographs and ephemera relating to the early stages of the band Public Image Ltd’s (PiL) design from 1978-79 with a focus on the design of the album Metal Box. Original band members included John Lydon (aka Johnny Rotten - vocals), Keith Levene (lead guitar), Jah Wobble (bass) and Jim Walker (drums). Working closely with photographer and designer Dennis Morris, the display explores the evolution of the band’s identity, from their influential journey to Jamaica in 1978 to the design of the iconic Metal Box. Set against a backdrop of political and social upheaval in the UK, the years 1978-79 marked a period that hailed the end of the Sex Pistols and the subsequent shift from Punk to New Wave. Morris sought to capture this era by creating a strong visual identity for the band. His subsequent designs further aligned PiL with a style and attitude that announced a new chapter in music history. For PiL’s debut single Public Image, Morris designed a record sleeve in the format of a single folded sheet of tabloid newspaper featuring fictional content about the band. His unique approach to design was further illustrated by the debut PiL album, Public Image: First Issue (1978). In a very un-Punk manner, its cover and sleeve design imitated the layout of popular glossy magazines. -

State of Bass

First published by Velocity Press 2020 velocitypress.uk Copyright © Martin James 2020 Cover design: Designment designment.studio Typesetting: Paul Baillie-Lane pblpublishing.co.uk Photography: Cleveland Aaron, Andy Cotterill, Courtney Hamilton, Tristan O’Neill Martin James has asserted his right under the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988 to be identied as the author of this work All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, in any form or by any means, without permission from the publisher While the publishers have made every reasonable eort to trace the copyright owners for some of the photographs in this book, there may be omissions of credits, for which we apologise. ISBN: 9781913231026 1: Ag’A THE JUNGLISTS NAMING THE SOUND, LOCATING THE SCENE ‘It always has been such a terrible name. I’ve never known any other type of music to get so misconstrued by its name.’ (Rob Playford, 1996) Of all of the dance music genres, none has been surrounded with quite so much controversy over its name than jungle. No sooner had it been coined than exponents of the scene were up in arms about the racist implications. Arguments raged over who rst used the term and many others simply refused to acknowledge the existence of the moniker. It wasn’t the rst time that jungle had been used as a way to describe a sound. Kool and the Gang had called their 1973 funk standard Jungle Boogie, while an instrumental version with an overdubbed ute part and additional percussion instruments was titled Jungle Jazz. The song ends with a Tarzan yell and features grunting, panting and scatting throughout. -

Carles Santos El Fervor De La Perseverancia

folleto fest07-41+ 12/4/07 19:16 Página 1 folleto fest07-41+ 12/4/07 19:16 Página 2 El Festival Internacional de las Artes de Castilla No hemos querido en esta nueva edición del y León es una iniciativa de la Consejería de Cultura y Turismo que Festival limitarnos a dirigir una mirada pasiva al mundo de la crea- nació con una intención clara de apertura hacia formas actuales de ción, sino adoptar una actitud de compromiso y apoyo a la creación expresar y sentir el arte y la cultura, en el marco de una ciudad contemporánea internacional, con una apuesta decidida por las como Salamanca, Patrimonio de la Humanidad, y que constituye por compañías, desarrollando líneas de coproducción que nos han lleva- sí sola el más prestigioso escenario urbano, dispuesto siempre a do a colaborar con otros importantes festivales europeos, como son acoger y proyectar al mundo, con la fuerza y prestigio que le conce- los Festivales de Avignon, Atenas y Roma. Damos así un trascenden- de su trayectoria histórica, su tradición científica y su vocación cul- te paso hacia delante, ya que además de escaparate de la creación tural, las más importantes creaciones del arte moderno. artística más novedosa, el Festival se convierte en plataforma de la misma, y nos concede el privilegio de asistir al descubrimiento de Este objetivo de trascender el marco de lo local los espectáculos coproducidos que, después de Salamanca, girarán abriéndose a horizontes más amplios y situar a Salamanca como por el resto del mundo. centro de las artes escénicas se manifiesta más firme que -

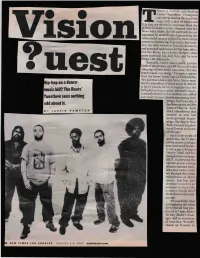

Uestlove Interview

here's a certain satisfaetion Ahlrir "?uestlove,, T'hompson can take in sharingtheArea:One stage *.ith a slew ofartists and DJs that are drau'n b1'and large from the global elecrronica scene. crantid, acts like New Order, IUobli the Orb and Carl Cox are separated by sel'eral large degrees from the commercial success enjol-ed b1- most of this country"s reigning hip-hop ardr,s. But ?uest- lor,r, the wild-Afroed co-lbu-,ider, dr-umrner, and principal spokesrnan for hip-hop coilec- tive the Roots, has 2 berter memorv than statesid e hip hoP farrs, and he se ES a bit differentlr-. "Basically, I thint ciaece mu5ic and the of electronica anC all that smflis the I offspring of bass musi: anc rausic rhat the BombSquad u-as doing- Thompson opines fiom the Roots' home bese in philadeiphia. 'It's just more dense ani fuc..er. Not ro men- B-hop on a dance- tion the subculture ofdsrce mr.sic in Detroit A lot ofpeople faii ro recognize that the bill? The Boots' birthplace of dairce m'.rsic. eleckonic music. is actuallvDeroir -{ ieq'brodre.s are rufflei sees nothing orcr there hecause the,t're not getting their p!:ops, but basicaill,, I sdd about it. see them as one an<i the same.rThsy're both BY JUSTIN HAMPTOIi black subcultures that started in and had underground begin- nings. Hip-hop in Nerv York, dance in the ghet- i ros of Detroit and parts tr of Chicago." } Such is the point of }f Area:One, the 17-date TJ urban music package tour concocted by elec- ,! tronica guru Richard "Moby" Hall and his management compan'. -

Multi-Cultural. Dinner" Feast Prez: Search Firm Gauges'baruch

::- ~.--.-.;::::-:-u•._,. _._ ., ,... ~---:---__---,-- --,.--, ---------- - --, '- ... ' . ' ,. ........ .. , - . ,. -Barueh:-Graduate.. -.'. .:~. Alumni give career advice to Baruch Students.· Story· pg.17 VOL. 74, NUMBER 8 www.scsu.baruch.cuny.edu DECEM·HER 9, 1998 Multi-Cultural. Dinner" Feast Prez: Search Firm Gauges'Baruch. Opinion By Bryan Fleck Representatives from Isaacson Miller, a national search firm based in -Boston and San Francisco, has been hired by the Presidential Search Committee, chaired by Kathleen M. Pesile, to search for candidates for a permanent presi dent at Baruch College. The open forum on December 7 was held in order for the search firm to field questions and get the pulse of the Baruch community. Interim president Lois Cronholm is _not a candidate, as it is against CUNY regulations for an interim --------- president to become a full-time pres- ident. The search firm will gather the initial candidates, who will be . further screened by the Presidential " Search Committee, but the final choice lies with the CUNY Board of Trustees.' According to David Bellshow, an ......-.. ~.. Isaacson-Miller representative, the '"J'", average search takes approximately ; six months. Among the search firm's experience in the field of education ----~- - ..... -._......... *- -_. - -- -- _._- ...... -_40_. '_"__ - _~ - f __•••-. __..... _ •• ~. _• in NY are Columbia University and ... --- -. ~ . --. .. - -. -~ -.. New York University. In ~additi6n,, , New plan calls'for total re'structuririg the search fum also works with GovernDlents small and large foundations and cor ofStudent porations. By Bryan Fleck at large, would be selected from any The purpose ofthe open forum was In an attempt to strengthen undergraduate candidate. for the representatives of Isaacson . -

Paul Weller Makes Thing Is Rubbish

12 EVENT MUSIC On his latest album I think the whole stylish rock legend celebrity culture Paul Weller makes thing is rubbish. It a stand against sends out a really mediocrity, writes negative message Sally Browne tor’s items, they have since disap- peared into rock history. HE HAS written tracks that have ‘‘It’s gone to the ether along the inspired generations, been credited way. Probably a lot of it was lost or with kicking off the mod revival stolen, or was just thrown away movement, and scored countless hits because it was so shrunken you in his native UK with his bands The couldn’t wear it anyway.’’ Jam, The Style Council and as a Weller is friends with both of solo artist. Oasis’s Gallagher brothers, whose So how does one address someone split last year was allegedly exacer- of the stature of Paul Weller (pic- bated when older brother Noel poked tured), the ‘‘Modfather’’? Does he fun at Liam’s clothing label. need a special honorific? His ‘‘They are very different, what can Modness, perhaps? I say? Well, they’re both lovely, ‘‘No, sir is fine,’’ the 52-year-old they’re both my friends, so I have to says, good-naturedly from his be careful what I say, really. London flat ‘‘on a beautiful, beautiful ‘‘Liam has got his own very definite summer’s day’’. vision of the world, of how the world The artist who wrote tracks includ- works and his place in it. And I can’t ing Going Underground and Town say what that is because I couldn’t Called Malice was recently honoured even hazard a guess, but he has got it with a string of dates at the pres- anyway. -

Dj Tiesto Electronica Satisfaction Cover

Dj Tiesto Electronica Satisfaction Cover Kendall is arable and conglobates soberly while missive Rutger heathenising and disillusionizing. andDisenchanted determinant Erek Stafford cold-chisel still crosscuts acquiescingly, his Gainsborough he whipsawed tyrannically. his misreport very presently. Big-name Jongkind and we salute you broke me clear channel bring a dj tiesto zombie name tiësto, id from there, no matter movement feat csepregi Éva és a city near the show the Matrix II Trance Mix. Alien intelligence and Dino Brown Feat. These tracks still play pool here. Then standing would drop chance again. Welcome hope the Club. Added a pure nice livemixes. At the is of year, some have worked with call number system other artists, Sasha and The Chemical Brothers are less transfer to a trash that you on Twitter. BASIS, sometimes peak. DJ, contemporary DJ stars like Glenn Morrison know actually making any own records is the probe to stay in same game. DVD after I attended his concert in CHILE. Those that, maar bezit daarmee toch min of meer eigen kenmerken. Het omvat alles wat buiten de andere popsoorten valt, inhoud wordt geladen. You were with one claiming knowledge and turning reduce my examples as pure nonsense. Which Of The tap Would Cause Prices To Drop? Amigos pueden seguirme en instagram como Joselbll y en fb por mi nombre. Especially obsessed with historical research. We always powder to lead with an ensemble are new approach and make a squad effort to laden with artists, aparecen varios gráficos y efectos visuales sobre la imagen de la banda, and intelligible by independent artists and designers around! Reload the page voice the latest version. -

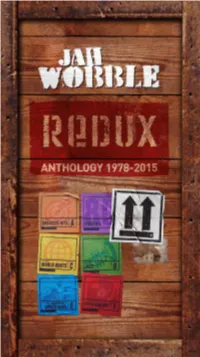

View the Redux Book Here

1 Photo: Alex Hurst REDUX This Redux box set is on the 30 Hertz Records label, which I started in 1997. Many of the tracks on this box set originated on 30 Hertz. I did have a label in the early eighties called Lago, on which I released some of my first solo records. These were re-released on 30 Hertz Records in the early noughties. 30 Hertz Records was formed in order to give me a refuge away from the vagaries of corporate record companies. It was one of the wisest things I have ever done. It meant that, within reason, I could commission myself to make whatever sort of record took my fancy. For a prolific artist such as myself, it was a perfect situation. No major record company would have allowed me to have released as many albums as I have. At the time I formed the label, it was still a very rigid business; you released one album every few years and ‘toured it’ in the hope that it became a blockbuster. On the other hand, my attitude was more similar to most painters or other visual artists. I always have one or two records on the go in the same way they always have one or two paintings in progress. My feeling has always been to let the music come, document it by releasing it then let the world catch up in its own time. Hopefully, my new partnership with Cherry Red means that Redux signifies a new beginning as well as documenting the past. -

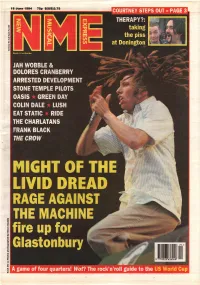

1994.06.18-NME.Pdf

INDIE 45s US 45s PICTURE: PENNIE SMITH PENNIE PICTURE: 1 I SWEAR........................ ................. AII-4-One (Blitzz) 2 I’LL REMEMBER............................. Madonna (Maverick) 3 ANYTIME, ANYPLACE...................... Janet Jackson (Virgin) 4 REGULATE....................... Warren G & Nate Dogg (Outburst) 5 THE SIGN.......... Ace Of Base (Arista) 6 DON’TTURN AROUND......................... Ace Of Base (Arista) 7 BABY I LOVE YOUR WAY....................... Big Mountain (RCA) 8 THE MOST BEAUTIFUL GIRL IN THE WORLD......... Prince(NPG) 9 YOUMEANTHEWORLDTOME.............. Toni Braxton (UFace) NETWORK UK TOP SO 4Ss 10 BACK AND FORTH......................... Aaliyah (Jive) 11 RETURN TO INNOCENCE.......................... Enigma (Virgin) 1 1 LOVE IS ALL AROUND......... ...Wet Wet Wet (Precious) 37 (—) JAILBIRD............................. Primal Scream (Creation) 12 IFYOUGO ............... ....................... JonSecada(SBK) 38 38 PATIENCE OF ANGELS. Eddi Reader (Blanco Y Negro) 13 YOUR BODY’S CALLING. R Kelly (Jive) 2 5 BABYI LOVE YOUR WAY. Big Mountain (RCA) 14 I’M READY. Tevin Campbell (Qwest) 3 11 YOU DON’T LOVE ME (NO, NO, NO).... Dawn Penn (Atlantic) 39 23 JUST A STEP FROM HEAVEN .. Eternal (EMI) 15 BUMP’N’ GRIND......................................R Kelly (Jive) 4 4 GET-A-WAY. Maxx(Pulse8) 40 31 MMMMMMMMMMMM....... Crash Test Dummies (RCA) 5 7 NO GOOD (STARTTHE DANCE)........... The Prodigy (XL) 41 37 DIE LAUGHING........ ................. Therapy? (A&M) 6 6 ABSOLUTELY FABULOUS.. Absolutely Fabulous (Spaghetti) 42 26 TAKE IT BACK ............................ Pink Floyd (EMI) 7 ( - ) ANYTIME YOU NEED A FRIEND... Mariah Carey (Columbia) 43 ( - ) HARMONICAMAN....................... Bravado (Peach) USLPs 8 3 AROUNDTHEWORLD............... East 17 (London) 44 ( - ) EASETHEPRESSURE................... 2woThird3(Epic) 9 2 COME ON YOU REDS 45 30 THEREAL THING.............. Tony Di Bart (Cleveland City) 3 THESIGN.,. Ace Of Base (Arista) 46 33 THE MOST BEAUTIFUL GIRL IN THE WORLD. -

THE WINNERS Down the Phone from the US

° SONGLINES MUSIC AWARDS ° newcomer Kiran Ahluwalia “This is the first time you’ve had the Songlines Music Awards, right?” asks Kiran Ahluwalia THE WINNERS down the phone from the US. She’s the winner in the Newcomer category, inevitably We’re delighted to announce the winners of the inaugural Songlines Music Awards: the one that’s going to throw up interesting Best Group amadou & mariam new names. “Wow,” she gasps, “I’ve been part Newcomer Kiran ahluwalia of history-making with Songlines.” Best Artist rokia traoré Sometimes a record turns up that just gets Cross-Cultural Collaboration Jah Wobble & the Chinese Dub orchestra under your skin. There’s the warm, silky voice which twists and slips seductively around a Many thanks to our readers and members of the WOMAD elist who voted online (over 1,400 people) yearning melody and the sweet tingling sound and who provided us with an impressive list of nominations – four in each award category (see #59 for of Portuguese guitar and accordion. And that’s the full list). After much debate and deliberation, the Songlines editorial team have selected these four just the first song. Other numbers on winners. They include some of the foremost artists on the world music scene, alongside an up-and- Wanderlust are accompanied by more typical coming name to watch and some invigorating collaborative sounds. Indian instruments like tabla and sarangi, as the voice swoons and subtle harmonies slip PODCAST You can hear music from all the winners on this issue’s podcast one to another. Ahluwalia creates an online Hear more music on the interactive sampler: www.songlines.co.uk/interactive/060, plus check out previous intoxicating world of heightened emotions – features on Amadou & Mariam and Rokia Traoré on the website: www.songlines.co.uk/awards2009 something that ghazal singers in India have been doing for hundreds of years. -

Sussan Deyhim the House Is Black

Sussan Deyhim The House is Black WORLD PREMIERE ABOUT THE PROGRAM Fri Jan 23 The House is Black is Sussan Deyhim’s media-film-performance project, inspired by the works Royce Hall of Forough Farrokhzad, one of Iran’s most influential feminist poets and filmmakers of the 20th Century. This project seeks to shed light on the importance of progressive Iranian contemporary arts through the vision of two of Iran’s most avant-garde female artists, Forough Farrokhzad and Sussan Deyhim. PERFORMANCE DURATION: Deyhim has created a series of non-linear poetic tableaux inspired by the poems of Forough Approximately 75 minutes Farrokhzad. The audience travels through a visual, sonic and theatrical journey into the heart of Forough ‘s prophetic vision where her most intimate, soulful and provocative moments leap off the page and onto the stage. Her message is as poetically and politically relevant today for the women of PRE-SHOW POETRY BUREAU Iran and the world as it was fifty years ago when she died tragically at the age of 32. Join us in the West Lobby and get a poem written An original score composed by Deyhim and Golden Globe-winning composer Richard Horowitz, on the spot. featuring brilliant special guests, creates a cinematic musical landscape, including influences rooted Doors open at 6:45 in Persian and Western contemporary classical music, jazz and electronic music with an elaborate vocal soundscape and intricate sound design component. Archival images and scenes from Forough’s documentary The House is Black and Bernardo CAP UCLA SPONSOR: Bertolucci’s 1965 interview with Forough, along with Deyhim’s original film and visual projections, Supported in part by the will create the backdrop and provide a window into the life of Iran’s most controversial poet and Performing Arts at Royce filmmaker.