Migration, Urbanisation, Primary Cities

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Section 124- Unpaid and Unclaimed Dividend

Sr No First Name Middle Name Last Name Address Pincode Folio Amount 1 ASHOK KUMAR GOLCHHA 305 ASHOKA CHAMBERS ADARSHNAGAR HYDERABAD 500063 0000000000B9A0011390 36.00 2 ADAMALI ABDULLABHOY 20, SUKEAS LANE, 3RD FLOOR, KOLKATA 700001 0000000000B9A0050954 150.00 3 AMAR MANOHAR MOTIWALA DR MOTIWALA'S CLINIC, SUNDARAM BUILDING VIKRAM SARABHAI MARG, OPP POLYTECHNIC AHMEDABAD 380015 0000000000B9A0102113 12.00 4 AMRATLAL BHAGWANDAS GANDHI 14 GULABPARK NEAR BASANT CINEMA CHEMBUR 400074 0000000000B9A0102806 30.00 5 ARVIND KUMAR DESAI H NO 2-1-563/2 NALLAKUNTA HYDERABAD 500044 0000000000B9A0106500 30.00 6 BIBISHAB S PATHAN 1005 DENA TOWER OPP ADUJAN PATIYA SURAT 395009 0000000000B9B0007570 144.00 7 BEENA DAVE 703 KRISHNA APT NEXT TO POISAR DEPOT OPP OUR LADY REMEDY SCHOOL S V ROAD, KANDIVILI (W) MUMBAI 400067 0000000000B9B0009430 30.00 8 BABULAL S LADHANI 9 ABDUL REHMAN STREET 3RD FLOOR ROOM NO 62 YUSUF BUILDING MUMBAI 400003 0000000000B9B0100587 30.00 9 BHAGWANDAS Z BAPHNA MAIN ROAD DAHANU DIST THANA W RLY MAHARASHTRA 401601 0000000000B9B0102431 48.00 10 BHARAT MOHANLAL VADALIA MAHADEVIA ROAD MANAVADAR GUJARAT 362630 0000000000B9B0103101 60.00 11 BHARATBHAI R PATEL 45 KRISHNA PARK SOC JASODA NAGAR RD NR GAUR NO KUVO PO GIDC VATVA AHMEDABAD 382445 0000000000B9B0103233 48.00 12 BHARATI PRAKASH HINDUJA 505 A NEEL KANTH 98 MARINE DRIVE P O BOX NO 2397 MUMBAI 400002 0000000000B9B0103411 60.00 13 BHASKAR SUBRAMANY FLAT NO 7 3RD FLOOR 41 SEA LAND CO OP HSG SOCIETY OPP HOTEL PRESIDENT CUFFE PARADE MUMBAI 400005 0000000000B9B0103985 96.00 14 BHASKER CHAMPAKLAL -

No. Sub Division Designation,Address & Telephone

No. Sub Division Designation,Address & Designation,Address & Designation,Address & Telephone Telephone Number of Assistant Telephone Number of Number of Government Information Information Officer Government Information Officer Officer 1 Office of the 1] Administrative Officer,Desk -1 1] Assistant Commissiner 1] Deputy Commissiner of Commissioner of {Confidential Br.},Office of the of Police,{Head Quarter- Police,{Head Quarter-1},Office of the Police,Mumbai Commissioner of Police, 1},Office of the Commissioner of Police, D.N.Road, D.N.Road,Mumbai-01,Telephone Commissioner of Police, Mumbai-01,Telephone No.2620043 No.22695451 D.N.Road, Mumbai-01, Telephone No.22624426 Confidential Report, Sr.Esstt., 2] Sr.Administrative Officer, Assistant Commissiner of Deputy Commissiner of Police, {Head Dept.Enquiry, Pay, Desk-3 {Sr.Esstt. Br.}, Office of Police, {Head Quarter- Quarter-1},Office of the Commissioner Licence, Welfare, the Commissioner of Police, 1},Office of the of Police, D.N.Road, Mumbai- Budget, Salary, D.N.Road,Mumbai-01, Telephone Commissioner of Police, 01,Telephone No.2620043 Retirdment No.22620810 D.N.Road, Mumbai-01, etc.Branches Telephone No.22624426 3] Sr.Administrative Officer,Desk - Assistant Commissiner of Deputy Commissiner of Police, {Head 5 {Dept.Enquiry} Br., Office of the Police, {Head Quarter- Quarter-1},Office of the Commissioner Commissioner of Police, 1},Office of the of Police, D.N.Road, Mumbai- D.N.Road,Mumbai-01,Telephone Commissioner of Police, 01,Telephone No.2620043 No.22611211 D.N.Road, Mumbai-01, Telephone -

Things-Ngos-Do.Pdf

THINGS NGOS DO CSR Today s closely knit with NGO and SHG activities. But NGOs are bounden to corporates in terms of patronage and financial support. Here, we look at some strikingly good work by NGOs and how corporates help them make it happen. Anil Nair There is the other side of CSR. The side that is far away from profits, return on investments and accruing depreciation benefits. To get that side of the story we met with several non-governmental organizations (NGOs) which form the linchpin of CSR network, its activities and outreach. Often, self-help group workers on the field told us, NGOs work as the bulwark against interests that try to subvert the system. Though NGOs have themselves been found wanting in several instances of vested interests, we spoke to some of the most accredited NGOs in Mumbai to hear about their mission, activities, outreach, problems and issues and expectations from the corporate sector. Aseema and Kherwadi Social Welfare Association work with street children and destitute youth. If the times are a changing for the CSR sector, Kishor Kher, President and trustee of Kherwadi Social Welfare Association explains it vividly: “Indian economy will be the world's largest in 30 years. The assumption of this growth is that 50 percent of India 's population under the age of 25 will contribute significantly to this growth. While this latent asset exists, it can only be productively utilised with a strategic plan.” So, he continues, Yuva Parivartan (his NGO) undertook the task eight years ago to provide livelihood training and placement to underprivileged youth and to make them participate in economic growth. -

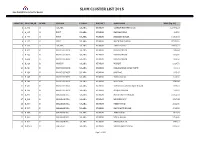

List of Slum Cluster 2015

SLUM CLUSTER LIST 2015 Slum Rehabilitation Authority, Mumbai OBJECTID CLUSTER_ID WARD VILLAGE TALUKA DISTRICT SLUM NAME AREA (Sq. M.) 1 A_001 A COLABA COLABA MUMBAI GANESH MURTHI NAGAR 120771.23 2 A_005 A FORT COLABA MUMBAI BANGALIPURA 318.50 3 A_006 A FORT COLABA MUMBAI NARIMAN NAGAR 14315.98 4 A_007 A FORT COLABA MUMBAI MACHIMAR NAGAR 37181.09 5 A_009 A COLABA COLABA MUMBAI GEETA NAGAR 26501.21 6 B_021 B PRINCESS DOCK COLABA MUMBAI DANA BANDAR 939.53 7 B_022 B PRINCESS DOCK COLABA MUMBAI DANA BANDAR 1292.90 8 B_023 B PRINCESS DOCK COLABA MUMBAI DANA BANDAR 318.67 9 B_029 B MANDVI COLABA MUMBAI MANDVI 1324.71 10 B_034 B PRINCESS DOCK COLABA MUMBAI NALABANDAR JOPAD PATTI 600.14 11 B_039 B PRINCESS DOCK COLABA MUMBAI JHOPDAS 908.47 12 B_045 B PRINCESS DOCK COLABA MUMBAI INDRA NAGAR 1026.09 13 B_046 B PRINCESS DOCK COLABA MUMBAI MAZGAON 1541.46 14 B_047 B PRINCESS DOCK COLABA MUMBAI SUBHASHCHANDRA BOSE NAGAR 848.16 15 B_049 B PRINCESS DOCK COLABA MUMBAI MASJID BANDAR 277.27 16 D_001 D MALABAR HILL COLABA MUMBAI MATA PARVATI NAGAR 21352.02 17 D_003 D MALABAR HILL COLABA MUMBAI BRANHDHARY 1597.88 18 D_006 D MALABAR HILL COLABA MUMBAI PREM NAGAR 3211.09 19 D_007 D MALABAR HILL COLABA MUMBAI NAVSHANTI NAGAR 4013.82 20 D_008 D MALABAR HILL COLABA MUMBAI ASHA NAGAR 1899.04 21 D_009 D MALABAR HILL COLABA MUMBAI SIMLA NAGAR 9706.69 22 D_010 D MALABAR HILL COLABA MUMBAI SHIVAJI NAGAR 1841.12 23 D_015A D GIRGAUM COLABA MUMBAI SIDHDHARTH NAGAR 2189.50 Page 1 of 101 SLUM CLUSTER LIST 2015 Slum Rehabilitation Authority, Mumbai OBJECTID CLUSTER_ID WARD VILLAGE TALUKA DISTRICT SLUM NAME AREA (Sq. -

Total List of MCGM and Private Facilities.Xlsx

MUNICIPAL CORPORATION OF GREATER MUMBAI MUNICIPAL DISPENSARIES SR SR WARD NAME OF THE MUNICIPAL DISPENSARY ADDRESS NO NO 1 1 COLABA MUNICIPALMUNICIPAL DISPENSARY 1ST FLOOR, COLOBA MARKET, LALA NIGAM ROAD, COLABA MUMBAI 400 005 SABOO SIDIQUE RD. MUNICIPAL DISPENSARY ( 2 2 SABU SIDDIQ ROAD, MUMBAI (UPGRADED) PALTAN RD.) 3 3 MARUTI LANE MUNICIPAL DISPENSARY MARUTI LANE,MUMBAI A 4 4 S B S ROAD. MUNICIPAL DISPENSARY 308, SHAHID BHAGATSINGH MARG, FORT, MUMBAI - 1. 5 5 HEAD OFFICE MUNICIPAL DISPENSARY HEAD OFFICE BUILDING, 2ND FLOOR, ANNEX BUILDING, MUMBAI - 1, 6 6 HEAD OFFICE AYURVEDIC MUNICIPAL DISPENSARY HEAD OFFICE BUILDING, 2ND FLOOR, ANNEX BUILDING, MUMBAI - 1, 7 1 SVP RD. MUNICIPAL DISPENSARY 259, SARDAR VALLABBHAI PATEL MARG, QUARTERS, A BLOCK, MAUJI RATHOD RD, NOOR BAUG, DONGRI, MUMBAI 400 8 2 WALPAKHADI MUNICIPAL DISPENSARY 009 9B 3 JAIL RD. UNANI MUNICIPAL DISPENSARY 259, SARDAR VALLABBHAI PATEL MARG, 10 4 KOLSA MOHALLA MUNICIPAL DISPENSARY 20, KOLSA STREET, KOLSA MOHALLA UNANI , PAYDHUNI 11 5 JAIL RD MUNICIPAL DISPENSARY 20, KOLSA STREET, KOLSA MOHALLA UNANI , PAYDHUNI CHANDANWADI SCHOOL, GR.FLOOR,CHANDANWADI,76-SHRIKANT PALEKAR 12 1 CHANDAN WADI MUNICIPAL DISPENSARY MARG,MARINELINES,MUM-002 13 2 THAKURDWAR MUNICIPAL DISPENSARY THAKURDWAR NAKA,MARINELINES,MUM-002 C PANJRAPOLE HEALTH POST, RAMA GALLI,2ND CROSS LANE,DUNCAN ROAD 14 3 PANJRAPOLE MUNICIPAL DISPENSARY MUMBAI - 400004 15 4 DUNCAN RD. MUNICIPAL DISPENSARY DUNCAN ROAD, 2ND CROSS GULLY 16 5 GHOGARI MOHALLA MUNICIPAL DISPENSARY HAJI HASAN AHMED BAZAR MARG, GOGRI MOHOLLA 17 1 NANA CHOWK MUNICIPAL DISPENSARY NANA CHOWK, FIRE BRIGADE COMPOUND, BYCULLA 18 2 R. S. NIMKAR MUNICIPAL DISPENSARY R.S NIMKAR MARG, FORAS ROAD, 19 3 R. -

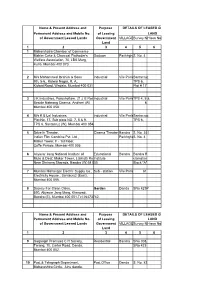

Name & Present Address and Purpose DETAILS of LEASED

INFORMATION ON LEASED GOVERNEMNT LANDS IN MUMBAI SUB DISTRICT TALUKA : ANDHERI Name & Present Address and Purpose DETAILS OF LEASED GOVERNMENT Permanent Address and Mobile No. of Leasing LAND of Government Leased Lands Government VILLAGESurvey No.Hissa No. Land 1 2 3 4 5 6 1 Maharshatra Chamber of Commerce Mahim Coke & Charcoal Flathoder's Godown ParikhgharS. No. 4 Welfare Association, 70, LBS Marg, Kurla, Mumbai 400 070. 2 M/s Mohammed Ibrahim & Sons Industrial Vile ParleSantacruz 9th, 5-6,, Kidwai Nagar, R. A., TPS 6, Kidwai Road, Wadala, Mumbai 400 031 Plot # 17 3 J K Industries, Purushottam, 21,J B RoadIndustrial Vile ParleTPS 4, 5 & Beside Nabrang Cinema, Andheri (W) 6 Mumbai 400 058. 4 M/s K B Lal Industries, Industrial Vile ParleSantacruz Plot No. 17, Sub plots NO. 7, 8 & 9. TPS 6, TPS 6, Santacruz (W), Mumbai 400 054. 5 Drive In Theatre, Cinema Theatre Bandra S. No. 341 Indian Film Combine Pvt. Ltd., ParkhgharS. No. 4 Maker Tower, F - 1st Floor, Cuffe Parade, Mumbai 400 005. 6 Aliyavar Jang National Institute of Educational Bandra Bandra Re Mute & Deaf, Maker Tower, Labhatti Road,Institute clamation Near Shrirang Sharada, Bandra (W) M 050 Block "A" 7 Mumbai Mahangar Electric Supply Co., Sub - station Vile Parle 61 Electricity House., Santacruz (East), Mumbai 400 055. 8 Society For Clean Cities, Garden Danda SNo 423P 590, Aliyavar Jang Marg, Kherwadi, Bandra (E), Mumbai 400 051.Tel 26473742. Name & Present Address and Purpose DETAILS OF LEASED GOVERNMENT Permanent Address and Mobile No. of Leasing LAND of Government Leased Lands Government VILLAGESurvey No.Hissa No. -

348 LTD Bus Time Schedule & Line Route

348 LTD bus time schedule & line map View In Website Mode 348 LTD Borivali Railway Station / बोरवली रेवे थानक (पू) The 348 LTD bus line Borivali Railway Station / बोरवली रेवे थानक (पू) has one route. For regular weekdays, their operation hours are: (1) Borivali Railway Station / बोरवली रेवे थानक (पू): 8:45 AM - 9:40 AM Use the Moovit App to ƒnd the closest 348 LTD bus station near you and ƒnd out when is the next 348 LTD bus arriving. Direction: Borivali Railway Station / बोरवली रेवे 348 LTD bus Time Schedule थानक (पू) Borivali Railway Station / बोरवली रेवे थानक (पू) Route 62 stops Timetable: VIEW LINE SCHEDULE Sunday 8:45 AM - 9:40 AM Monday 8:45 AM - 9:40 AM Chunabhatti / चुनाभी Tuesday 8:45 AM - 9:40 AM Chunabhatti Wednesday 8:45 AM - 9:40 AM Central Labour Institute Thursday 8:45 AM - 9:40 AM Rani Laxmibai Chowk (Sion) Friday 8:45 AM - 9:40 AM Rani Laxmibai Chowk (Sion) Saturday 8:45 AM - 9:40 AM Rani Laxmibai Chowk-Sion Road No 3, Mumbai Dharavi Pumping Station 348 LTD bus Info Direction: Borivali Railway Station / बोरवली रेवे Kala Killa थानक (पू) Stops: 62 Trip Duration: 70 min Dharavi Koliwada Line Summary: Chunabhatti / चुनाभी, Chunabhatti, Central Labour Institute, Rani Laxmibai Chowk Dharavi T Junction / Tapase Chowk (Sion), Rani Laxmibai Chowk (Sion), Rani Laxmibai Chowk-Sion, Dharavi Pumping Station, Kala Killa, Kala Nagar (Bandra-E) Dharavi Koliwada, Dharavi T Junction / Tapase Sion Bandra Link Road, Mumbai Chowk, Kala Nagar (Bandra-E), Kala Nagar (Bandra- E), Kherwadi Junction, Kherwadi Junction, Cardinal Kala Nagar (Bandra-E) -

Brihanmumbai Mahanagarpalika

BRIHANMUMBAI MAHANAGARPALIKA Section 4 Manuals as per provision of RTI Act, 2005 of H/East Ward Public Health Department Insecticide Branch Address - Office of Pest Control Office, Ram Mandir Road, Kherwadi Signal, Bandra East, Mumbai 400 051. 1 INDEX Sr. No. Section No. Name of the manual Page No Introduction 1 4 (1) (b) (I) Particulars of Organization, functions & duties Powers and Duties of Officers of Public Health 2 4 (1) (b) (II) Department Procedure followed in decision making process 3 4 (1) (b) (III) including channels of supervision & accountability 4 4 (1) (b) (IV) Norms sets for the discharge of functions Rules, Regulations, Instructions Manuals & 5 4 (1) (b) (V) Records held or under the control for discharging functions A Statement of the Categories of the documents 6 4 (1) (b) (VI) that are held by it or under its control The Particulars of any arrangements that exists for consultation with or representation by members of 7 4 (1) (b) (VII) the public in relation to the formulation of its policy A Statement of Boards, councils, Committees & 8 4 (1) (b) (VIII) other Bodies constituted as its part 9 4 (1) (b) (IX) Directory of Officers 10 4 (1) (b) (X) Pay Grades of Officers The Budget allocated to each Agency Particulars 11 4 (1) (b) (XI) of all plans, proposed expenditure & reports on disbursement made 12 4 (1) (b) (XII) The manner of execution of subsidy programs Particulars of recipients of concessions, permits, 13 4 (1) (b) (XIII) authorization granted by it 14 4 (1) (b) (XIV) Details in respect of information available on Electronic form Particulars of the facilities available to citizens for 15 4 (1) (b) (XV) obtaining information The names designations & other particulars of the 16 4 (1) (b) (XVI) Public Information Officers 4 (1) (b) 17 Other Useful Information (XVII) 2 INTRODUCTION Right to Information Act, 2005 This handbook of “Right to Information Act, 2005” is prepared to facilitate the implementation of the act by giving information about the Pest Control Department H/East ward to the Citizens. -

Hiranadani Gardens Lake Castle - Powai, Mum… 3BHK Residential Apartments in Powai, Mumbai

https://www.propertywala.com/hiranadani-gardens-lake-castle-mumbai Hiranadani Gardens Lake Castle - Powai, Mum… 3BHK Residential Apartments in Powai, Mumbai. Hiranadani Group presents beautiful 3BHK Residential apartments in Hiranadani Gardens Lake Castle at Powai, Mumbai. Project ID : J811905822 Builder: Hiranadani Group Properties: Apartments / Flats Location: Hiranadani Gardens Lake Castle, Powai, Mumbai - 400076 (Maharashtra) Completion Date: Nov, 2014 Status: Started Description Hiranadani Gardens Lake Castle is one of the very special residential projects of a well-known real estate group Hiranadani Group. The project is located in one of the most in-demanded and prime location of the Mumbai that is Powai. The beautiful Lake Castle is offering luxurious 3BHK residential apartments in various sizes in affordable price which can be easily affordable by you. The Lake Castle contains best amenities as well as features of modern life style and it is located in that place which is very far from the noisy and polluted environment of Mumbai. You can easily reach the Lake Castle from each and every places of the Mumbai city. Location - Powai, Mumbai Type - 3BHK Residential Apartments Price - On Request Amenities Sports Facility Kids Play Area Club House Gym Vastu Compliant Intercom Landscape Garden/Park Firefighting Equipment Wi-fi Connectivity Rain Water Harvesting Property Staff Car Parking Lift The Hiranandani Group has come a long way to be identified worldwide for their modern state of the art combined used township projects in Powai & Thane, both of which have become recommended residential and commercial locations in as well as around Mumbai. Surendra Hiranandani is the engineering master behind the Hiranandani Group outstanding popularity for quality along with innovation. -

SIEMENS LIMITED List of Outstanding Warrants As on 18Th March, 2020 (Payment Date:- 14Th February, 2020) Sr No

SIEMENS LIMITED List of outstanding warrants as on 18th March, 2020 (Payment date:- 14th February, 2020) Sr No. First Name Middle Name Last Name Address Pincode Folio Amount 1 A P RAJALAKSHMY A-6 VARUN I RAHEJA TOWNSHIP MALAD EAST MUMBAI 400097 A0004682 49.00 2 A RAJENDRAN B-4, KUMARAGURU FLATS 12, SIVAKAMIPURAM 4TH STREET, TIRUVANMIYUR CHENNAI 600041 1203690000017100 56.00 3 A G MANJULA 619 J II BLOCK RAJAJINAGAR BANGALORE 560010 A6000651 70.00 4 A GEORGE NO.35, SNEHA, 2ND CROSS, 2ND MAIN, CAMBRIDGE LAYOUT EXTENSION, ULSOOR, BANGALORE 560008 IN30023912036499 70.00 5 A GEORGE NO.263 MURPHY TOWN ULSOOR BANGALORE 560008 A6000604 70.00 6 A JAGADEESWARAN 37A TATABAD STREET NO 7 COIMBATORE COIMBATORE 641012 IN30108022118859 70.00 7 A PADMAJA G44 MADHURA NAGAR COLONY YOUSUFGUDA HYDERABAD 500037 A0005290 70.00 8 A RAJAGOPAL 260/4 10TH K M HOSUR ROAD BOMMANAHALLI BANGALORE 560068 A6000603 70.00 9 A G HARIKRISHNAN 'GOKULUM' 62 STJOHNS ROAD BANGALORE 560042 A6000410 140.00 10 A NARAYANASWAMY NO: 60 3RD CROSS CUBBON PET BANGALORE 560002 A6000582 140.00 11 A RAMESH KUMAR 10 VELLALAR STREET VALAYALKARA STREET KARUR 639001 IN30039413174239 140.00 12 A SUDHEENDHRA NO.68 5TH CROSS N.R.COLONY. BANGALORE 560019 A6000451 140.00 13 A THILAKACHAR NO.6275TH CROSS 1ST STAGE 2ND BLOCK BANASANKARI BANGALORE 560050 A6000418 140.00 14 A YUVARAJ # 18 5TH CROSS V G S LAYOUT EJIPURA BANGALORE 560047 A6000426 140.00 15 A KRISHNA MURTHY # 411 AMRUTH NAGAR ANDHRA MUNIAPPA LAYOUT CHELEKERE KALYAN NAGAR POST BANGALORE 560043 A6000358 210.00 16 A MANI NO 12 ANANDHI NILAYAM -

Hon. Chief Minister Presents Two Too Good Projects to Mumbaikars

Hon. Chief Minister presents two too good projects to Mumbaikars Northbound arm of Kherwadi flyover thrown open Bhoomipujan of BKC-EEH Connector performed Mumbai, April 19, 2015 – The Honorable Chief Minister Mr. Devendra Fadnavis, today, presented two too good projects to Mumbaikars – the Northbound arm of the Kherwadi flyover and an elevated road connecting Bandra-Kurla Complex with Eastern Express Highway. “The city of Mumbai will flourish once it is provided with handy connectivity”, said Mr. Fadnavis. “Both – the 580-meter Kherwadi flyover and the 1.6-km BKC-EEH Connector – will benefit the Bandra-Kurla Complex which is city’s crucial and main growth centre. These projects will certainly facilitate commuters visiting the complex which is buzzing with activities at international level”, said Mr. Fadnavis further. He also expected MMRDA to construct an iconic building to provide a global financial centre to the city. He further said that such projects can bring back the lost glory of the city. The 1.6-km long Elevated Road connecting Bandra-Kurla Complex with the Eastern Express Highway will cross Mithi river, Central and Harbour Rail lines and will cost Rs. 156 crore. The Industries and Guardian Minister (Mumbai City District) Mr. Subhash Desai termed Bandra- Kurla Complex as “the financial centre” of the financial capital of the country. Mr. Fadnavis and Mr. Desai both expressed the need to complete projects with the same zeal and enthusiasm as has been shown by the consultants and contractors while completing the Kherwadi flyover. While the Southbound arm of the Kherwadi flyover was completed in 226 days, the Northbound arm of the flyover has been completed in a mere 171 days. -

Introduction Garden & Trees

BRIHANMUMBAI MAHANAGARPALIKA Section 4 Manuals as per provision of RTI Act, 2005 of H/East Ward Garden Department. Address - Office of Assistant Commissioner H/East Ward, Basemen, Plot No. 137 T.P.S.5, Road No.2, Prabhat Colony,Santacruz(E), Mumbai-55 1 Introduction Garden & Trees The corporation has decentralized most of the main departments functioning at the city central level under Departmental Heads, and placed the relevant sections of these Departments under the Assistant Commissioner of the Ward. Horticulture Assistant & Jr. Tree Officer are the officers appointed to look after works of Garden & Trees department at ward level. Jr. Tree Officer is subordinate to Tree Officer appointed to implement various provisions of ‘The Maharashtra (Urban Areas) Protection & Preservation of Trees Act, 1975 (As modified upto 3 rd November 2006). As per Central Right to Information Act 2005, Jr. Tree Officer is appointed as Public Information Officer for Trees in the ward jurisdiction and As per Maharashtra Public Records Act-2005 and Maharashtra Public Records Act Rules -2007, he is appointed as Record Officer for Trees in ward jurisdiction. As per section 63(D) of MMC Act, 1888 (As modified upto 13 th November 2006), development & maintenance of public parks, gardens & recreational spaces is the discretionary duty of MCGM. Horticulture Assistant is appointed to maintain gardens, recreational grounds, play grounds in the Ward. As per Central Right to Information Act 2005, Horticulture Assistant is appointed as Public Information Officer for gardens, recreational grounds, play grounds in the ward jurisdiction and As per Maharashtra Public Records Act-2005 and Maharashtra Public Records Act Rules -2007, he is appointed as Record Officer for Trees in ward jurisdiction.