“Fractures, Alliances, and Mobilizations: Emerging Analyses of the Tea Party Movement”

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Mitchell Moss-CV.Docx.Docx

Mitchell L. Moss Page 1 MITCHELL L. MOSS New York University 295 Lafayette Street New York, N.Y. 10012 (212) 998-7547 [email protected] PROFESSIONAL EXPERIENCE 2010-present Director, Rudin Center for Transportation Policy and Management, Robert F. Wagner Graduate School of Public Service, New York University 1987-2002 Director, Taub Urban Research Center; Henry Hart Rice Professor of Urban Policy and Planning, Robert F. Wagner Graduate School of Public Service, New York University 1992-1997 Paulette Goddard Professor of Urban Planning Robert F. Wagner Graduate School of Public Service, New York University 1983-1991 Deputy to the Chairman, Governor's Council on Fiscal and Economic Priorities 1987-1989 Director, Urban Planning Program, Graduate School of Public Administration, New York University 1981-1983 Chairman, Interactive Telecommunications Program, Tisch School of the Arts, New York University 1979-1981 Associate Director, Center for Science and Technology Policy, New York University 1973-1987 Assistant and Associate Professor of Public Administration and Planning (successively), New York University 1972-1973 Instructor, School of Public Administration and Research Associate, Center for Urban Affairs, University of Southern California EDUCATION B.A., 1969 Northwestern University, Political Science M.A., 1970 University of Washington, Political Science Ph.D., 1975 University of Southern California, Urban Studies Mitchell L. Moss Page 2 PUBLICATIONS BOOKS Telecommunications and Productivity, Addison-Wesley Publishing Co.: Reading, MA, 1981 (editor and author of chapter). ARTICLES "The Stafford Act and Priorities for Reform," The Journal of Homeland Security and Emergency Management, 2009. "New York: The City of the Telephone,” New York Talk Exchange, 2008. "From Beaver Pelts to Derivatives. -

MAP Act Coalition Letter Freedomworks

April 13, 2021 Dear Members of Congress, We, the undersigned organizations representing millions of Americans nationwide highly concerned by our country’s unsustainable fiscal trajectory, write in support of the Maximizing America’s Prosperity (MAP) Act, to be introduced by Rep. Kevin Brady (R-Texas) and Sen. Mike Braun (R-Ind.). As we stare down a mounting national debt of over $28 trillion, the MAP Act presents a long-term solution to our ever-worsening spending patterns by implementing a Swiss-style debt brake that would prevent large budget deficits and increased national debt. Since the introduction of the MAP Act in the 116th Congress, our national debt has increased by more than 25 percent, totaling six trillion dollars higher than the $22 trillion we faced less than two years ago in July of 2019. Similarly, nearly 25 percent of all U.S. debt accumulated since the inception of our country has come since the outset of the COVID-19 pandemic. Now more than ever, it is critical that legislators take a serious look at the fiscal situation we find ourselves in, with a budget deficit for Fiscal Year 2020 of $3.132 trillion and a projected share of the national debt held by the public of 102.3 percent of GDP. While markets continue to finance our debt in the current moment, the simple and unavoidable fact remains that our country is not immune from the basic economics of massive debt, that history tells us leads to inevitable crisis. Increased levels of debt even before a resulting crisis slows economic activity -- a phenomenon referred to as “debt drag” -- which especially as we seek recovery from COVID-19 lockdowns, our nation cannot afford. -

Culture Wars' Reloaded: Trump, Anti-Political Correctness and the Right's 'Free Speech' Hypocrisy

The 'Culture Wars' Reloaded: Trump, Anti-Political Correctness and the Right's 'Free Speech' Hypocrisy Dr. Valerie Scatamburlo-D'Annibale University of Windsor, Windsor, Ontario, Canada Abstract This article explores how Donald Trump capitalized on the right's decades-long, carefully choreographed and well-financed campaign against political correctness in relation to the broader strategy of 'cultural conservatism.' It provides an historical overview of various iterations of this campaign, discusses the mainstream media's complicity in promulgating conservative talking points about higher education at the height of the 1990s 'culture wars,' examines the reconfigured anti- PC/pro-free speech crusade of recent years, its contemporary currency in the Trump era and the implications for academia and educational policy. Keywords: political correctness, culture wars, free speech, cultural conservatism, critical pedagogy Introduction More than two years after Donald Trump's ascendancy to the White House, post-mortems of the 2016 American election continue to explore the factors that propelled him to office. Some have pointed to the spread of right-wing populism in the aftermath of the 2008 global financial crisis that culminated in Brexit in Europe and Trump's victory (Kagarlitsky, 2017; Tufts & Thomas, 2017) while Fuchs (2018) lays bare the deleterious role of social media in facilitating the rise of authoritarianism in the U.S. and elsewhere. Other 69 | P a g e The 'Culture Wars' Reloaded: Trump, Anti-Political Correctness and the Right's 'Free Speech' Hypocrisy explanations refer to deep-rooted misogyny that worked against Hillary Clinton (Wilz, 2016), a backlash against Barack Obama, sedimented racism and the demonization of diversity as a public good (Major, Blodorn and Blascovich, 2016; Shafer, 2017). -

I Used to Be Antifa Gabriel Nadales

I Used to be Antifa Gabriel Nadales There was a time in my life when I was angry, bitter, and deeply unhappy. I wanted to lash out at the whole “fascist” system—the greedy, heartless power structure that didn’t care about me or the rest of society’s innocent victims, a system that had robbed, beaten and stolen from my ancestors. The whole corrupt edifice deserved to be brought down, reduced to rubble. I was a perfect recruit for Antifa, the left-wing group which claims to fight against fascism. And so, I became a member. Now I was one of those who had the guts to fight against “the fascists” who were exploiting disadvantaged people. I wasn’t a ‘card-carrying’ antifascist—there is no such thing as an official Antifa membership. But I was ready at a moment’s notice to slip on the black mask and march in what Antifa calls “the black bloc”—a cadre of other black-clad Antifa members— to taunt police and destroy property. Antifa stands for “antifascist,” but that’s purposefully deceptive. For one thing, the very name is calibrated so that anyone who dares to criticize the group or its tactics can be labeled “fascist.” This allows Antifa to justify violence against all who dare stand up or speak out against them. A few groups boldly declare themselves Antifa, like “Rose City Antifa” in Portland. But most don’t, preferring to avoid the negative publicity. That’s part of Antifa’s appeal—and strength: It’s hard to pin down. -

C00490045 Restore Our Future, Inc. $4116274

Independent Expenditure Table 2 Committees/Persons Reporting Independent Expenditures from January 1, 2011 through December 31, 2011 ID # Committee/Individual Amount C00490045 RESTORE OUR FUTURE, INC. $4,116,274 C00499731 MAKE US GREAT AGAIN, INC $3,793,524 C00501098 OUR DESTINY PAC $2,323,481 C00000935 DEMOCRATIC CONGRESSIONAL CAMPAIGN COMMITTEE $1,759,111 C00495028 HOUSE MAJORITY PAC $1,073,851 C00487363 AMERICAN CROSSROADS $1,016,349 C00075820 NATIONAL REPUBLICAN CONGRESSIONAL COMMITTEE $810,157 C00507525 WINNING OUR FUTURE $788,381 C00442319 REPUBLICAN MAJORITY CAMPAIGN $710,400 C00503417 RED WHITE AND BLUE FUND $573,680 C00448696 SENATE CONSERVATIVES FUND $479,867 C90012758 CITIZENS FOR A WORKING AMERICA INC. $475,000 C00484642 MAJORITY PAC $471,728 C00495861 PRIORITIES USA ACTION $306,229 C00495010 CAMPAIGN TO DEFEAT BARACK OBAMA $266,432 C00499020 FREEDOMWORKS FOR AMERICA $241,542 C00504241 9-9-9 FUND $226,530 C00498261 RESTORING PROSPERITY FUND $202,873 C00503870 RETHINK PAC $156,000 C00432260 CLUB FOR GROWTH PAC $145,459 C90011057 NATIONAL ORGANIZATION FOR MARRIAGE $142,841 C00454074 OUR COUNTRY DESERVES BETTER PAC - TEAPARTYEXPRESS.ORG $141,526 C00473918 WOMEN VOTE! $133,976 C00508317 LEADERS FOR FAMILIES SUPER PAC INC $122,767 C00488486 COMMUNICATIONS WORKERS OF AMERICA WORKING VOICES $107,000 C00492116 COOPERATIVE OF AMERICAN PHYSICIANS IE COMMITTEE $102,184 C90011230 AMERICAN ACTION NETWORK INC $96,694 C00348540 1199 SERVICE EMPLOYEES INT'L UNION FEDERAL POLITICAL ACTION FUND $83,975 C00505081 STRONG AMERICA NOW SUPER PAC -

The Second Tea Party-Freedomworks Survey Report

FreedomWorks Supporters: 2012 Campaign Activity, 2016 Preferences, and the Future of the Republican Party Ronald B. Rapoport and Meredith G. Dost Department of Government College of William and Mary September 11, 2013 ©Ronald B. Rapoport Introduction Since our first survey of FreedomWorks subscribers in December 2011, a lot has happened: the 2012 Republican nomination contests, the 2012 presidential and Congressional elections, continuing debates over the budget, Obamacare, and immigration, and the creation of a Republican Party Growth and Opportunity Project (GOP). In all of these, the Tea Party has played an important role. Tea Party-backed candidates won Republican nominations in contested primaries in Arizona, Indiana, Texas and Missouri, and two of the four won elections. Even though Romney was not a Tea Party favorite (see the first report), the movement pushed him and other Republican Congressional/Senatorial candidates (e.g., Orin Hatch) to engage the Tea Party agenda even when they had not done so before. In this report, we will focus on the role of FreedomWorks subscribers in the 2012 nomination and general election campaigns. We’ll also discuss their role in—and view of—the Republican Party as we move forward to 2014 and 2016. This is the first of multiple reports on the March-June 2013 survey, which re-interviewed 2,613 FreedomWorks subscribers who also filled out the December 2011 survey. Key findings: Rallying around Romney (pp. 3-4) Between the 2011 and 2013 surveys, Romney’s evaluations went up significantly from 2:1 positive to 4:1 positive surveys. By the end of the nomination process Romney and Santorum had become the two top nomination choices but neither received over a quarter of the sample’s support. -

Our 2020 Form

PUBLIC DISCLOSURE COPY Return of Organization Exempt From Income Tax OMB No. 1545-0047 Form 990 Under section 501(c), 527, or 4947(a)(1) of the Internal Revenue Code (except private foundations) 2020 a Department of the Treasury Do not enter social security numbers on this form as it may be made public. Open to Public Internal Revenue Service a Go to www.irs.gov/Form990 for instructions and the latest information. Inspection A For the 2020 calendar year, or tax year beginning , 2020, and ending , 20 B Check if applicable: C Name of organization LEADERSHIP INSTITUTE D Employer identification number Address change Doing business as 51-0235174 Name change Number and street (or P.O. box if mail is not delivered to street address) Room/suite E Telephone number Initial return 1101 N HIGHLAND STREET (703) 247-2000 Final return/terminated City or town, state or province, country, and ZIP or foreign postal code Amended return ARLINGTON, VA 22201 G Gross receipts $ 24,354,691 Application pending F Name and address of principal officer: MORTON BLACKWELL H(a) Is this a group return for subordinates? Yes ✔ No SAME AS C ABOVE H(b) Are all subordinates included? Yes No I Tax-exempt status: 501(c)(3) 501(c) ( ) ` (insert no.) 4947(a)(1) or 527 If “No,” attach a list. See instructions J Website: a WWW.LEADERSHIPINSTITUTE.ORG H(c) Group exemption number a K Form of organization: Corporation Trust Association Other a L Year of formation: 1979 M State of legal domicile: VA Part I Summary 1 Briefly describe the organization’s mission or most significant activities: EDUCATE PEOPLE FOR SUCCESSFUL PARTICIPATION IN GOVERNMENT, POLITICS AND MEDIA. -

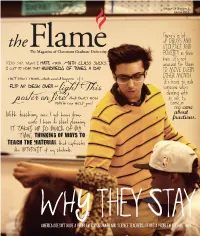

Spring 2013 COME Volume 14 Number 3

the Flame The Magazine of Claremont Graduate University Spring 2013 COME Volume 14 Number 3 The Flame is published by Claremont Graduate University 150 East Tenth Street Claremont, California 91711 ©2013 by Claremont Graduate BACK TO University Director of University Communications Esther Wiley Managing Editor Brendan Babish CAMPUS Art Director Shari Fournier-O’Leary News Editor Rod Leveque Online Editor WITHOUT Sheila Lefor Editorial Contributors Mandy Bennett Dean Gerstein Kelsey Kimmel Kevin Riel LEAVING Emily Schuck Rachel Tie Director of Alumni Services Monika Moore Distribution Manager HOME Mandy Bennett Every semester CGU holds scores of lectures, performances, and other events Photographers Marc Campos on our campus. Jonathan Gibby Carlos Puma On Claremont Graduate University’s YouTube channel you can view the full video of many William Vasta Tom Zasadzinski of our most notable speakers, events, and faculty members: www.youtube.com/cgunews. Illustration Below is just a small sample of our recent postings: Thomas James Claremont Graduate University, founded in 1925, focuses exclusively on graduate-level study. It is a member of the Claremont Colleges, Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi, distinguished professor of psychology in CGU’s School of a consortium of seven independent Behavioral and Organizational Sciences, talks about why one of the great challenges institutions. to positive psychology is to help keep material consumption within sustainable limits. President Deborah A. Freund Executive Vice President and Provost Jacob Adams Jack Scott, former chancellor of the California Community Colleges, and Senior Vice President for Finance Carl Cohn, member of the California Board of Education, discuss educational and Administration politics in California, with CGU Provost Jacob Adams moderating. -

Measuring the News and Its Impact on Democracy COLLOQUIUM PAPER Duncan J

Measuring the news and its impact on democracy COLLOQUIUM PAPER Duncan J. Wattsa,b,c,1, David M. Rothschildd, and Markus Mobiuse aDepartment of Computer and Information Science, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, PA 19104; bThe Annenberg School of Communication, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, PA 19104; cOperations, Information, and Decisions Department, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, PA 19104; dMicrosoft Research, New York, NY 10012; and eMicrosoft Research, Cambridge, MA 02142 Edited by Dietram A. Scheufele, University of Wisconsin–Madison, Madison, WI, and accepted by Editorial Board Member Susan T. Fiske February 21, 2021 (received for review November 8, 2019) Since the 2016 US presidential election, the deliberate spread of pro-Clinton articles.” In turn, they estimated that “if one fake misinformation online, and on social media in particular, has news article were about as persuasive as one TV campaign ad, generated extraordinary concern, in large part because of its the fake news in our database would have changed vote shares by potential effects on public opinion, political polarization, and an amount on the order of hundredths of a percentage point,” ultimately democratic decision making. Recently, however, a roughly two orders of magnitude less than needed to influence handful of papers have argued that both the prevalence and the election outcome. Subsequent studies have found similarly consumption of “fake news” per se is extremely low compared with other types of news and news-relevant content. -

Health Care Reform, Rhetoric, Ethics and Economics at the End of Life

Mississippi College Law Review Volume 29 Issue 2 Vol. 29 Iss. 2 Article 7 2010 A Missed Opportunity: Health Care Reform, Rhetoric, Ethics and Economics at the End of Life Joshua E. Perry Follow this and additional works at: https://dc.law.mc.edu/lawreview Part of the Law Commons Custom Citation 29 Miss. C. L. Rev. 409 (2010) This Article is brought to you for free and open access by MC Law Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Mississippi College Law Review by an authorized editor of MC Law Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. A MISSED OPPORTUNITY: HEALTH CARE REFORM, RHETORIC, ETHICS AND ECONOMICS AT THE END OF LIFE Joshua E. Perry* [T]he chronically ill and those toward the end of their lives are accounting for potentially 80 percent of the total health care bill . .. [T]here is going to have to be a conversation that is guided by doctors, scientists, ethicists. And then there is going to have to be a very difficult democratic conversation that takes place. It is very difficult to imagine the country making those decisions just through the normal political channels. And that's part of why you have to have some in- dependent group that can give you guidance. It's not deter- minative, but I think [it] has to be able to give you some guidance. - Barack Obama, President of the United States' I. INTRODUCTION On January 24, 2010, my grandmother, June Fuqua Walker, did some- thing that we will all one day do. -

CONSTITUTING CONSERVATISM: the GOLDWATER/PAUL ANALOG by Eric Edward English B. A. in Communication, Philosophy, and Political Sc

CORE Metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk Provided by D-Scholarship@Pitt CONSTITUTING CONSERVATISM: THE GOLDWATER/PAUL ANALOG by Eric Edward English B. A. in Communication, Philosophy, and Political Science, University of Pittsburgh, 2001 M. A. in Communication, University of Pittsburgh, 2003 Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of The Dietrich School of Arts and Sciences in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of Pittsburgh 2013 UNIVERSITY OF PITTSBURGH DIETRICH SCHOOL OF ARTS AND SCIENCES This dissertation was presented by Eric Edward English It was defended on November 13, 2013 and approved by Don Bialostosky, PhD, Professor, English Gordon Mitchell, PhD, Associate Professor, Communication John Poulakos, PhD, Associate Professor, Communication Dissertation Director: John Lyne, PhD, Professor, Communication ii Copyright © by Eric Edward English 2013 iii CONSTITUTING CONSERVATISM: THE GOLDWATER/PAUL ANALOG Eric Edward English, PhD University of Pittsburgh, 2013 Barry Goldwater’s 1960 campaign text The Conscience of a Conservative delivered a message of individual freedom and strictly limited government power in order to unite the fractured American conservative movement around a set of core principles. The coalition Goldwater helped constitute among libertarians, traditionalists, and anticommunists would dominate American politics for several decades. By 2008, however, the cracks in this edifice had become apparent, and the future of the movement was in clear jeopardy. That year, Ron Paul’s campaign text The Revolution: A Manifesto appeared, offering a broad vision of “freedom” strikingly similar to that of Goldwater, but differing in certain key ways. This book was an effort to reconstitute the conservative movement by expelling the hawkish descendants of the anticommunists and depicting the noninterventionist views of pre-Cold War conservatives like Robert Taft as the “true” conservative position. -

The Tea Party: a Party Within a Party a Dissertation Submitted to The

The Tea Party: A Party Within a Party A Dissertation submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences of Georgetown University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Government By Rachel Marie Blum, M.A. Washington, DC March 22, 2016 Copyright c 2016 by Rachel Marie Blum All Rights Reserved ii The Tea Party: A Party Within a Party Rachel Marie Blum, M.A. Dissertation Advisor: Hans Noel, Ph.D. Abstract It is little surprise that conservatives were politically disaffected in early 2009, or that highly conservative individuals mobilized as a political movement to protest ‘big government’ and Obama’s election. Rather than merely directing its animus against liberals, the Tea Party mobilized against the Republican Party in primaries and beyond. This dissertation draws from original survey, interview, Tea Party blog, and social network datasets to explain the Tea Party’s strategy for mobilization as a ‘Party within a Party’. Integrating new data on the Tea Party with existing theories of political parties, I show that the Tea Party’s strategy transcends the focused aims of a party faction. Instead, it works to co-opt the Republican Party’s political and electoral machinery in order to gain control of the party. This dissertation offers new insights on the Tea Party while developing a theory of intra-party mobilization that endures beyond the Tea Party. Index words: Dissertations, Government, Political Science, Political Parties, Tea Party iii Dedication To M.L.B., and all others who are stronger than they know.