Pittwater Road Conservation Area, Manly Final Draft History

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Store Locations

Store Locations ACT Freddy Frapples Freska Fruit Go Troppo Shop G Shop 106, Westfield Woden 40 Collie Street 30 Cooleman Court Keltie Street Fyshwick ACT 2609 Weston ACT 2611 Woden ACT 2606 IGA Express Supabarn Supabarn Shop 22 15 Kingsland Parade 8 Gwydir Square 58 Bailey's Corner Casey ACT 2913 Maribyrnong Avenue Canberra ACT 2601 Kaleen ACT 2617 Supabarn Supabarn Supabarn Shop 1 56 Abena Avenue Kesteven Street Clift Crescent Crace ACT 2911 Florey ACT 2615 Richardson ACT 2905 Supabarn Supabarn Tom's Superfruit 66 Giles Street Shop 4 Belconnen Markets Kingston ACT 2604 5 Watson Place 10 Lathlain Street Watson ACT 2602 Belconnen ACT 2167 Ziggy's Ziggy's Fyshwick Markets Belconnen Markets 36 Mildura Street 10 Lathlain Street Fyshwick ACT 2609 Belconnen ACT 2167 NSW Adams Apple Antico's North Bridge Arena's Deli Café e Cucina Shop 110, Westfield Hurstville 79 Sailors Bay Road 908 Military Road 276 Forest Road North Bridge NSW 2063 Mosman NSW 2088 Hurstville NSW 2220 Australian Asparagus Banana George Banana Joe's Fruit Markets 1380 Pacific Highway 39 Selems Parade 258 Illawarra Road Turramurra NSW 2074 Revesby NSW 2212 Marrickville NSW 2204 Benzat Holdings Best Fresh Best Fresh Level 1 54 President Avenue Shop 2A, Cnr Eton Street 340 Bay Street Caringbah NSW 2229 & President Avenue Brighton Le Sands NSW 2216 Sutherland NSW 2232 Blackheath Vegie Patch Bobbin Head Fruit Market Broomes Fruit and Vegetable 234 Great Western Highway 276 Bobbin Head Road 439 Banna Avenue Blackheath NSW2785 North Turramurra NSW 2074 Griffith NSW 2680 1 Store Locations -

Viva Energy REIT Portfolio

Property Portfolio as at 31 December 2018 ADDRESS SUBURB STATE/ CAP RATE CARRYING MAJOR TENANT TERRITORY VALUE LEASE EXPIRY Cnr Nettleford Street & Lathlain Drive Belconnen ACT 6.18% $10,180,000 2034 Cnr Cohen & Josephson Street Belconnen ACT 6.22% $3,494,183 2027 Cnr Mort Street & Girrahween Street Braddon ACT 5.75% $4,240,000 2028 Lhotsky Street Charnwood ACT 6.69% $7,070,000 2033 17 Strangways Street Curtin ACT 6.74% $3,933,191 2028 25 Hopetoun Circuit Deakin ACT 6.49% $4,657,265 2030 Cnr Ipswich & Wiluna Street Fyshwick ACT 6.51% $2,840,000 2027 20 Springvale Drive Hawker ACT 6.50% $5,360,000 2031 Cnr Canberra Avenue & Flinders Way Manuka ACT 6.18% $8,100,000 2033 172 Melrose Drive Phillip ACT 6.00% $5,010,000 2030 Rylah Crescent Wanniassa ACT 6.49% $3,120,000 2027 252 Princes Highway Albion Park NSW 6.28% $6,041,239 2031 Cnr David Street & Guinea Street Albury NSW 7.08% $5,273,140 2031 562 Botany Road Alexandria NSW 4.79% $12,178,139 2034 124-126 Johnston Street Annandale NSW 4.25% $4,496,752 2027 89-93 Marsh Street Armidale NSW 8.76% $3,386,315 2028 Cnr Avalon Parade & Barrenjoey Road Avalon NSW 4.51% $4,190,223 2027 884-888 Hume Highway (Cnr Strickland Street) Bass Hill NSW 4.99% $4,225,892 2028 198 Beach Road Batehaven NSW 7.08% $5,374,877 2031 298 Stewart Street (Cnr Rocket Street) Bathurst NSW 6.53% $6,010,223 2029 59 Durham Street Bathurst NSW 7.00% $6,810,000 2033 Cnr Windsor Road & Olive Street Baulkham Hills NSW 4.75% $10,020,000 2028 Cnr Pacifi c Highway & Maude Street Belmont NSW 6.19% $3,876,317 2030 797 Pacifi c Highway -

Download DIGGIN' SYDNEY

EDITION 6 APRIL 2018 VINYL LOVERS’ TOUR GUIDE STAY COOL SELIM MP3 MINIDISCS VINYL NOW AVAILABLE ZONE D M IMPORTS SOUL DIGGIN' SYDNEY VINYL LOVERS' TOUR GUIDE DIGGERS LEGEND: SECONDHAND VINYL LP/EP/45 NEW VINYL / CDs / DVDs BOOKS / MUSIC RELATED & MORE Touring record stores is a great way EASTSIDE to see a city. This guide is put together Just to the East of the CBD – across Hyde with that in mind and uses Sydney’s CBD Park – is East Sydney. Indie, arty and as a starting point. You’ll also find some chock full of creatives and great food. It’s useful transport tips under all the regional kinda like Sydney’s Melbourne, except that subheadings. For those shops further the Inner West can also claim to have that excellent vibe (albeit further from city). A afield, overnighters may be in order, but short walk across Hyde Park or the Domain, hey, the promise of a crate at the end of or under the viaducts from Haymarket gets the rainbow might just be enough to tip you Eastside, where you’ll find a 4km-long the scales in favour of an adventure! ridge of indie retail, food, drink, night spots and boutique hotels. SYDNEY (CBD) The most obvious way to go Eastside is We start in the middle of Sydney’s CBD Oxford Street which starts at the South-East at Town Hall. Right behind the Queen corner of Hyde Park. Just a couple of blocks Victoria Building you’ll find Red Eye Records. up Oxford, turn right into Crown Street to get From here you have two options: head to the Record Store, TITLE Store and Suzie North to Birdland and Mojo Record Bar. -

Intersection Improvements on Pittwater Road, Collaroy Community Consultation Report

Intersection improvements on Pittwater Road, Collaroy Community Consultation Report 1 Intersection improvements on Pittwater Road, Collaroy: Community Consultation Report – February 2017 RMS 17.067, ISBN: 978-1-925582-57-4 Executive summary The NSW Government is taking action to deliver transport improvements for the Northern Beaches, including an integrated program of service and infrastructure improvements to deliver a new B-Line bus service. As part of the B-Line program we proposed to improve intersections along Pittwater Road, Collaroy. This report provides a summary of Transport for NSW’s community and stakeholder consultation in November and December on the proposal to improve safety, traffic flow and the reliability of bus travel times on Pittwater Road, Collaroy. The proposal includes: building six right turn bays for southbound traffic on Pittwater Road turning right into local roads, including at Stuart Street, Ramsay Street, Frazer Street, Jenkins Street, Homestead Avenue and Ocean Grove building a right turn bay for northbound traffic turning right from Pittwater Road into Brissenden Avenue building a right turn bay for northbound traffic turning right from Pittwater Road into Collaroy Surf Lifesaving Club, including a new driveway into the club car park. This will result in the loss of one parking space in the Collaroy Surf Lifesaving Club installing a part time ‘No right turn’ sign on Pittwater Road at Eastbank Avenue, restricting southbound motorists on Pittwater Road from turning right into Eastbank Avenue during -

AMH Stockists • Information Is Current As of January 2018 • Stock Is Subject to Availability and Is at the Discretion of the Bookshop

AMH Stockists • Information is current as of January 2018 • Stock is subject to availability and is at the discretion of the bookshop AUSTRALIAN CAPITAL TERRITORY Store Address Phone PSA Bookzone* Pharmaceutical Society of Australia 02 6283 4777 *PSA Members only Level, 1, 25 Geils Court Deakin 2600 EMAIL: [email protected] The Co-op ANU ANU 02 6249 6244 Pop Up Village, Demountable T20 ANU Campus 2601 EMAIL: [email protected] The Co-op University of University of Canberra 02 6251 2481 Canberra Building 1, Level B The Concourse 2600 EMAIL: [email protected] The Co-op ADFA ADFA 02 6257 3467 Building 33,Academy House Northcott Drive Campbell 2612 EMAIL: [email protected] NEW SOUTH WALES Store Address Phone James Bennett Pty Ltd Unit 3 02 8988 5000 114 Old Pittwater Road Brookvale PSA Bookzone* Pharmaceutical Society of Australia 02 9431 1100 *PSA Members only Level 1 134 Willoughby Road CROWS NEST NSW 2065 The Co-op ACU North ACU North Sydney 02 9959 4683 Sydney 12-16 Berry Street North Sydney 2060 EMAIL: [email protected] The Co-op ACU Strathfield Edmond Rice Building 02 9746 6567 25A Barker Road Strathfield 2135 EMAIL: [email protected] The Co-op CSU Building C5 02 6332 3722 Bathurst Bathurst 2795 0467 807 452 EMAIL: [email protected] The Co-op Sydney CBD Shop 2 02 6065 5551 153 Phillip Street Sydney 2000 EMAIL: [email protected] The Co-op Ourimbah University of Newcastle 02 4362 2796 Shop 1 10 Chittway Road Ourimbah 2258 EMAIL: [email protected] The Co-op CSU Booroom Street 02 6933 1180 -

02 9970 6385 38 Lake Park Road, North Narrabeen NSW 2101 Email: [email protected] for All Groups

Group Functions Phone: 02 9913 7845 Toll Free: 1800 008 845 Fax: 02 9970 6385 38 Lake Park Road, North Narrabeen NSW 2101 Email: [email protected] www.sydneylakeside.com.au For All Groups OVERVIEW Sydney Lakeside Holiday Park is situated in the beautiful Sydney Northern Beaches in Narrabeen. It’s situated right on the beach and next to the lake and bushland. It’s the perfect place to escape the hustle bustle of the city but close enough to venture into the city and enjoy everything Sydney has to offer. Public transport is available including buses and ferry’s to get you where you need to go. You won’t be disappointed by the facilities and range of modern self-contained accommodation available to suit your group. There’s a conference/meeting room that comfortably fits approximately 80 guests (theatre style) and you will have full use of the projector and media set up. Upon request, we can provide a tea and coffee station (please note, you must supply your own cups). There’s also a couple of BBQ’s on the veranda and undercover outdoor seating – perfect for your morning tea and lunch breaks. Oven Lovin Wood Fire Pizzas who are at the park every weekend between September and April. Self-catering is the way to do it at Syd- ney Lakeside. We have everything you need in the fully equipped camp kitch- en and you can book this out for your group to feed them at certain times throughout your stay. If you need any suggestions on local catering compa- nies, please let us know and we will try to point you in the right direction. -

Pittwater Road Conservation Area Review

Pittwater Road Conservation Area Review - Summary of Comments Initial comment period from 24 April to 12 June 2017 – 15 submissions and 26 nominations for the working group received on Your Say. Any personal details or identifying words have been removed, as have any comments not related to the PRCA. Spelling mistakes have been corrected. There are topic overlaps in some of the themes. What do you appreciate about the character of the PRCA? What makes it unique? Character and feel • I love the fact that Manly has character and is not a bland suburb full of buildings that all look the same. It is a historic suburb of Sydney and we should treasure this. • The Conservation Area is an example of what people love about living in, and visiting Manly. It's a relatively quiet, mid-density residential area with enough local businesses such as shops, cafes, restaurants and bars, to sustain its residents and attract some visitors, but not too many to make it over-touristy and overcrowded. This combined with the preserved charm of a quintessential Australian beach side suburb is what makes it so special. Some of the streets have immense character and show how heritage can successfully be combined with the modern, and how residential can co-exist with commercial. • I appreciate that the area has character . It is not bland like Dee Why. I like the fact that houses 100 years old (mainly well maintained or tastefully extended ) are side by side with modern units. • The character homes from the Federation and Edwardian era give Manly its distinct character and it is vital to preserve this, and protect it from inappropriate developments which destroy the character of the area. -

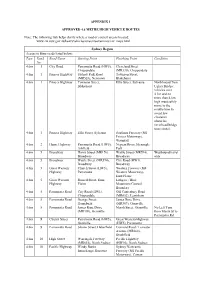

APPENDIX 1 APPROVED 4.6 METRE HIGH VEHICLE ROUTES Note: The

APPENDIX 1 APPROVED 4.6 METRE HIGH VEHICLE ROUTES Note: The following link helps clarify where a road or council area is located: www.rta.nsw.gov.au/heavyvehicles/oversizeovermass/rav_maps.html Sydney Region Access to State roads listed below: Type Road Road Name Starting Point Finishing Point Condition No 4.6m 1 City Road Parramatta Road (HW5), Cleveland Street Chippendale (MR330), Chippendale 4.6m 1 Princes Highway Sydney Park Road Townson Street, (MR528), Newtown Blakehurst 4.6m 1 Princes Highway Townson Street, Ellis Street, Sylvania Northbound Tom Blakehurst Ugly's Bridge: vehicles over 4.3m and no more than 4.6m high must safely move to the middle lane to avoid low clearance obstacles (overhead bridge truss struts). 4.6m 1 Princes Highway Ellis Street, Sylvania Southern Freeway (M1 Princes Motorway), Waterfall 4.6m 2 Hume Highway Parramatta Road (HW5), Nepean River, Menangle Ashfield Park 4.6m 5 Broadway Harris Street (MR170), Wattle Street (MR594), Westbound travel Broadway Broadway only 4.6m 5 Broadway Wattle Street (MR594), City Road (HW1), Broadway Broadway 4.6m 5 Great Western Church Street (HW5), Western Freeway (M4 Highway Parramatta Western Motorway), Emu Plains 4.6m 5 Great Western Russell Street, Emu Lithgow / Blue Highway Plains Mountains Council Boundary 4.6m 5 Parramatta Road City Road (HW1), Old Canterbury Road Chippendale (MR652), Lewisham 4.6m 5 Parramatta Road George Street, James Ruse Drive Homebush (MR309), Granville 4.6m 5 Parramatta Road James Ruse Drive Marsh Street, Granville No Left Turn (MR309), Granville -

Mona Vale / Pittwater / Clifton Gardens Via Woolloomooloo / Potts Point to Scots – TSC 1 and TSC 14

Mona Vale / Pittwater / Clifton Gardens via Woolloomooloo / Potts Point to Scots – TSC 1 and TSC 14 Mornings Time Bus Stop Street 6:40am • Pittwater Road, Mona Vale – first bus stop just before Bungan Lane (C) Pittwater Road (R) Roundabout at Park Street (R) Barrenjoey Road (C) Pittwater Road 6:55am • Dee Why (Howard Avenue) at bus stop (after B-Line stop) (C) Pittwater Road 7:06am Dee Why (just past Pacific Parade near Coles) (C) Pittwater Road Veer left onto Pittwater Road opposite Warringah Mall 7:15am • Manly Vale (after Kentwell Road) 7:16am • Manly Vale (corner just before Oliver Street) (C) Pittwater Road (R) Kenneth Street (L) Burnt Bridge Creek Deviation (C) Manly Road (C) Spit Road (L) Stanton Road (R) Moruben Road (R) Mandolong Road (L) Military Road • (C) Military Road • (C) Bradleys Head Road 7:30am • Bradleys Head Road before Thompson Street (Clifton Gardens) (R) Whiting Beach Road (R) Prince Albert Street • Prince Albert Street corner Lennox Street • Prince Albert Street corner Union Street (L) Queen Street 7:34am • Corner Queen Street, Raglan Street and Canrobert Street (C) Canrobert Street (R) Shadforth Street (L) Avenue Road • Avenue Road before Canrobert Street roundabout (C) Avenue Road (R) Cowles Road • (L) Military Road (C) Military Road 7:37am • Military Road/Spofforth Street outside IGA (C) Military Road 7:39am • Bus stop near Watson Street, Neutral Bay (L) Warringah Freeway (C) Bus Lane (C) Cahill Expressway (bus lane) (C) Sydney Harbour Bridge (L) Cahill Expressway (over Circular Quay) (R) Domain Tunnel (C) Eastern -

Private and Public Bus Information

Private and Public Bus Information Transport to and from Campus 2017 Students can travel to and from the School campus on the School's own private buses or on the public/government bus services. The Pittwater House bus system allows us to know who is on our buses at all times. This system offers considerable advantages in the event of an emergency or where we need to communicate with parents quickly. It is a condition of use of the School’s private buses that Pittwater House Student Cards are scanned upon boarding and alighting the bus. Private Bus Services The School runs four buses around areas of the North Shore and the Northern Beaches to assist many of our students who are not conveniently served by commercial or government services. The morning bus service drops students at the Westmoreland Avenue entrance. A teacher on duty escorts students from the Junior Schools to buses in Westmoreland Avenue each afternoon. Costs The costs per trip (including GST) for 2017 are set at the following rates: Fare Type Cost Booked Fare $4.25 per trip This is a flat rate fare with no discount for siblings. Booked Casual Fare $6.00 per trip This fare applies ONLY where a casual booking has been made using Skoolbag at least 1 working day prior to the journey and you have received a confirmation from the school that this booking has been received and a seat is available. Unbooked Casual Fare $15.00 per trip For safety and capacity reasons we do not wish to take unbooked casual fares. -

The Australian Capital Territory New South Wales

Names and electoral office addresses of Federal Members of Parliament The Australian Capital Territory ......................................................................................................... 1 New South Wales ............................................................................................................................... 1 Northern Territory .............................................................................................................................. 4 Queensland ........................................................................................................................................ 4 South Australia .................................................................................................................................. 6 Tasmania ........................................................................................................................................... 6 Victoria ............................................................................................................................................... 7 Western Australia .............................................................................................................................. 9 How to address Members of Parliament ........................................................................... 10 The Australian Capital Territory Ms Gai Brodtmann, MP Hon Dr Andrew Leigh, MP 205 Anketell St, Unit 8/1 Torrens St, Tuggeranong ACT, 2900 Braddon ACT, 2612 New South Wales Hon Anthony Abbott, -

Bilgola House Research.Pdf

Bilgola House Research BILGOLA COTTAGE BILGOLA BEACH, between Newport end Avalon Something Special in a Seaside Home Commodious Cottage, containing 3 bedrooms, living-room, bathroom, kitchen laundry, sleep-out verandahs Large garage Beautifully furnished Linen and cutlery Nominal rent to approved tenant Apply WENTWORTH HOTEL LTD_ Advertising. (1931, February 25). The Sydney Morning Herald (NSW : 1842 - 1954), p. 4. Retrieved from http://nla.gov.au/nla.news- article16756926 BILGOLA COTTAGE BILGOLA BEACH To Let Furnished containing largc living room, piano two double bedrooms maid’s room kitchen laundry bothioom shower room sleep out verandahs 1 wall bed and 2 single beds no linen Garage all conveniences electric light and running water. Surf and Swimming Pool Rent £7/7/ per week for 1 month or £5/5/ for two months RICHARD STANTON and SONS LTD _133 Pitt s rcet TW1256 Advertising. (1932, November 15). The Sydney Morning Herald(NSW : 1842 - 1954), p. 13. Retrieved from http://nla.gov.au/nla.news- article16930860 ' Bilgola Beach. Fix this text HOTELS AND HOLIDAY RESORTS BILGOLA BEACH BILGOLA BEACH between Palm Beach and Avalon large Furnished Bungalow right at beach amongst palms with beautiful gardens Most exclusive spot on the const Two bedrooms large lounge and living rooms spacious verandahs and sleep out maid’s quarters and garage Immediate possession to approved tenant For Inspection ring Sole Letting Agents RICHARD STANTON and SONS LTD 133 Pitt street SYDNEY BW1256ot T T STAPI.ETON and CO LTD Avalon BeachOffice Phone Y9155 Advertising. (1936, December 31). The Sydney Morning Herald(NSW : 1842 - 1954), p. 16. Retrieved from http://nla.gov.au/nla.news- article17298736 HOUSES AND LAND FOR SALE.