Brian Fauteux, University of Wisconsin-Madison

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Anne Sexton and Sylvia Plath from a Kristevan Perspective

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by OpenGrey Repository Transforming the Law of One: Anne Sexton and Sylvia Plath from a Kristevan Perspective A thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy By Areen Ghazi Khalifeh School of Arts, Brunel University November 2010 ii Abstract A recent trend in the study of Anne Sexton and Sylvia Plath often dissociates Confessional poetry from the subject of the writer and her biography, claiming that the artist is in full control of her work and that her art does not have naïve mimetic qualities. However, this study proposes that subjective attributes, namely negativity and abjection, enable a powerful transformative dialectic. Specifically, it demonstrates that an emphasis on the subjective can help manifest the process of transgressing the law of One. The law of One asserts a patriarchal, monotheistic law as a social closed system and can be opposed to the bodily drives and its open dynamism. This project asserts that unique, creative voices are derived from that which is individual and personal and thus, readings of Confessional poetry are in fact best served by acknowledgment of the subjective. In order to stress the subject of the artist in Confessionalism, this study employed a psychoanalytical Kristevan approach. This enables consideration of the subject not only in terms of the straightforward narration of her life, but also in relation to her poetic language and the process of creativity where instinctual drives are at work. This study further applies a feminist reading to the subject‘s poetic language and its ability to transgress the law, not necessarily in the political, macrocosmic sense of the word, but rather on the microcosmic, subjective level. -

Mad Men (AMC 2007-2015): Relato, Discurso, Ejes Temáticos

Revista Estudios, (36), 2018. ISSN 1659-3316 Junio 2018-Noviembre 2018 Rodríguez Jiménez Leda III Sección: Arte, arquitectura y cine 1 Mad Men (AMC 2007-2015): relato, discurso, ejes temáticos Leda Rodríguez Jiménez. Universidad de Costa Rica, Costa Rica [email protected] https://orcid.org /0000-0002-6235-5507 Recibido: 13 de febrero de 2018 Aceptado: 30 de marzo de 2018 Resumen El presente artículo propone un acercamiento a la serie de televisión Mad Men (AMC, 2007-2015) del guionista, director y productor norteamericano Matthew Weiner. Primeramente, el análisis se enfoca en el relato como suceso y como discurso. Esto quiere decir que considera tanto la instancia relatora –quién o qué narra- como los aspectos que competen a la recepción de la serie –a quién o a qué le narra- y, por tanto, a las diversas propiedades narrativas orientadas a la construcción de la mirada. En segundo término, el ejercicio analítico discurre sobre tres grandes ejes temáticos que, para quién escribe estas líneas, organizan buena parte de la estructura que compone el mundo representado. Estos ejes son: la prostitución como marca (identitaria y corporativa), la maternidad como obstáculo y la mujer como relato masculino. Aunque el artículo tiene sentido en sí mismo, se constituye como la continuación de un trabajo anterior que versa, grosso modo, sobre los espacios, las temporalidades y la forma del relato. Mad Men (AMC, 2007-2015): story, discourse and key ideas Palabras Clave: Series de televisión; Mad Men; relato; discurso; ejes temáticos Abstract This article approaches the television series Mad Men (2007-2015) by scriptwriter, director, and producer Matthew Weiner. -

Libro De Actas

MAD MEN WOMAN Raquel Crisóstomo Gálvez Facultad de Ciencias de la Comunicación Universitat Internacional de Catalunya [email protected] Resumen: Mad Men aporta una mirada histórica a la vez que una imagen sobre la sociedad y los usos de nuestro contexto actual. La construcción de los personajes masculinos en esta ficción ha dado lugar a una extensa literatura analítica; pero no tantos han sido los textos que abordan los personajes femeninos como indispensables. Es interesante explorar más en profundidad los arquetipos que yacen tras las mujeres principales de Mad Men: Joan, Betty y Peggy, y también tras las secundarias Rachel Menken, Sally y Megan Draper, todas ellas de relevancia para la imagen de la mujer en la ficción actual y para entender nuestra propia época. Esta comunicación pretende estudiar los personajes femeninos de Mad men en un momento en el que debido al prestigio de esta serie han surgido otras ficciones que miran hacia la misma década aportando personajes femeninos que se suman al imaginario serial, como las protagonistas de Pan Am; la británica The Hour; o Masters of Sex. Palabras claves: Mad Men, mujeres, Betty Draper, Joan, Peggy, años 60 1. Introducción El cine y las series de televisión ofrecen la posibilidad de la reconstrucción del pasado, por lo que ayudan a la percepción del mismo en la memoria colectiva (Erreguerena, 2013: 181). Los tiempos pasados, así como la imagen que conservamos de ellos ayudan a definir los roles sociales y las dinámicas y relaciones del presente. Por ello es importante ver como la multipremiada serie Mad Men aporta su perspectiva a la imagen de las mujeres en la década de los 60: La serie no retrata sólo la América de esos años, retrata el germen de la sociedad actual, por tanto también es un retrato de nuestros orígenes, de nuestras raíces, de nosotros mismos, con nuestros vicios y virtudes. -

Narrative Configuration, Completion, and the Televisual Episode / Season / Series

GRAAT On-Line issue #15 April 2014 Full of Wholes: Narrative Configuration, Completion, and the Televisual Episode / Season / Series Matthew Poland The Ohio State University “The end of a melody is not its goal: but nonetheless, had the melody not reached its end it would not have reached its goal either. A parable.” Friedrich Nietzsche What do we talk about when we talk about endings? In one sense, of course, we talk about movement—from absorption to apprehension, from immersion to interpretation: the ending as a threshold whose crossing ushers us outside the warm abode of the text and into a space of retrospective understanding. Peter Brooks has famously called an ending “the consummation (as well as the consumption) of its sense- making” (52). In aligning the structural function of narrative closure with the Freudian death drive, he suggests that all narrative actions ultimately point toward their culmination: The sense of a beginning, then, must in some important way be determined by the sense of an ending. We might say that we are able to read present moments—in literature and, by extension, in life—as endowed with narrative meaning only because we read them in 76 anticipation of the structuring power of those endings that will retrospectively give them the order and significance of plot. (94) This tendency to read a narrative ending as the final capstone that makes legible all that has come before is buttressed by a privileging of aesthetic wholes and all that they entail: unity, symmetry, teleology. To speak of an ending is to speak of the limit that decides a narrative’s shape, that makes clear the boundaries of a text and renders it an intelligible whole to be considered, deciphered, appraised. -

Pontifícia Universidade Católica Mariana Ayres Tavares Mad

Pontifícia Universidade Católica do Rio de Janeiro Mariana Ayres Tavares Mad Men: Uma história cultural da Publicidade Dissertação de Mestrado Dissertação apresentada como requisito parcial para obtenção do grau de Mestre pelo Programa de Pós- graduação em Comunicação Social do Departamento de Comunicação da PUC-Rio. Orientador: Prof. Everardo Pereira Guimarães Rocha Rio de Janeiro, Setembro de 2016 Pontifícia Universidade Católica do Rio de Janeiro Mariana Ayres Tavares Mad Men: Uma história cultural da Publicidade Dissertação de Mestrado Dissertação apresentada como requisito parcial para a obtenção do grau de Mestre pelo Programa de Pós- Graduação em Comunicação Social do Departamento de Comunicação Social do Centro de Ciências Sociais da PUC-Rio. Aprovada pela Comissão Examinadora abaixo assinada. Prof. Everardo Pereira Guimarães Rocha Orientador Departamento de Comunicação Social - PUC-Rio Profa. Lígia Campos de Cerqueira Lana Departamento de Comunicação Social - PUC-Rio Prof. Guilherme Nery Atem Departamento de Ciências Sociais - PUC-Rio Prof.ª Mônica Herz Vice-Decana de Pós-Graduação do CCS Rio de Janeiro, 23 de setembro de 2016 Todos os direitos reservados. É proibida a reprodução total ou parcial do trabalho sem autorização da universidade, da autora e do orientador. Mariana Ayres Tavares Graduou-se em Comunicação Social, com habilitação em Publicidade, na Universidade Federal Fluminense em 2012. Cursou especialização em Pesquisa de Mercado e Opinião Pública na Universidade do Estado do Rio de Janeiro, em 2014. Ficha Catalográfica Tavares, Mariana Ayres Mad Men : uma história cultural da publicida- de / Mariana Ayres Tavares Vasconcelos ; orien- tadora: Everardo Pereira Guimarães Rocha. – 2016. 118 f. : il. color. ; 30 cm Dissertação (mestrado)–Pontifícia Universi- dade Católica do Rio de Janeiro, Departamento de Comunicação Social, 2016. -

Université De Montréal La Série Mad Men: Une Élégie De La Révolution

Université de Montréal La série Mad Men: une élégie de la révolution créative dans les années soixante. Par Felicia Traistaru Département d’histoire Faculté des arts et des sciences Mémoire présenté à la Faculté des études supérieures En vue de l’obtention du grade de Maitre ès art (M.A) en histoire Août 2017 © Felicia Mihali, 2017 Université de Montréal Faculté des études supérieures Ce mémoire intitulé : La série Mad Men et la publicité dans les années soixante : une élégie de la révolution créative. Présenté par Felicia Traistaru A été évalué par un jury composé par les personnes suivantes : Yakov Rabkin Président-rapporteur Bruno Ramirez Directeur de recherche Marta Boni Membre du jury iii RÉSUMÉ Ce mémoire est consacré à l’analyse de la télésérie américaine Mad Men en tant que reflet de la révolution créative aux États-Unis. À travers la fictive agence de publicité Sterling Cooper & Partners et de son charismatique directeur artistique, Don Draper, la série personnifie la culture corporatiste des cols blancs et les nouveaux défis encourus par l’homme de l’organisation dans les années soixante. Basée sur la méthode de l’historicisme, cette analyse historique met en évidence la manière dont Mad Men incarne cette décennie à partir des sources populaires telles que les romans, les films ou les magazines. Ce type de documents sont pris par les créateurs de la série comme l’expression des certaines valeurs et attitudes des années soixante mais aussi bien comme outil pour la critique des idées consacrées. Mad Men nous permet de comprendre la manière dont la révolution des techniques publicitaires se déroule dans le décor d’une société où les grands enjeux restent encore non résolus. -

O Przemijaniu Mitu — Mad Men I Kres „Amerykañskiej Niewinnoœci”

Studia Filmoznawcze 34 Wroc³aw 2013 Patrycja W³odek Uniwersytet Opolski O PRZEMIJANIU MITU — MAD MEN I KRES „AMERYKAÑSKIEJ NIEWINNOŒCI” Lata 50. XX wieku w Stanach Zjednoczonych często zwane są „ostatnią dekadą amerykańskiej niewinności” i jest to określenie funkcjonujące zarówno w dyskursie naukowym, jak i języku potocznym. Lata 50. „były najszczęśliwszą epoką w hi- storii Stanów Zjednoczonych — when things were going on — za którą jeszcze wszyscy tęsknią. Ekstaza potęgi, potęga nad potęgami”1. Kres owego powojenne- go „samo-zwodzenia [...] świata wysprzątanego do czysta”2 — który rozciągał się też na początek lat 60. — nastąpił symbolicznie 22 listopada 1963 roku w Dallas. Przyczyn zmian, którym Ameryka uległa później, badacze będą — w zależności od opcji politycznej (i w uproszczeniu) — doszukiwać się albo bardziej po stronie kontrkultury, albo raczej w wybuchu wojny w Wietnamie i w jej konsekwencjach, nie tylko geopolitycznych, ale przede wszystkim społecznych. Określenie „samo- -zwodzenie” (self-deception) użyte przez Michaela Wooda — także w kontekście kina z epoki triumfów all American Marylin Monroe i Doris Day — wskazuje jed- nak na pewną cechę owych czasów, często umykającą ich nostalgicznie nastawio- nym apologetom. Każe bowiem zadać sobie pytanie — czy kiedykolwiek w ogóle istniało coś takiego, jak „amerykańska niewinność”? Wydaje się, że zagadnienie to — badane przez przedstawicieli wielu dziedzin — stało się szczególnie interesujące także dla filmowców w XXI wieku. Nie dlatego, że wcześniej pomijano tę dekadę; oczywiście tak nie było — już na bieżąco poszczególni twórcy Hollywood, między innymi subwersywnie wykorzystując melodramat, czyli jeden z najsilniej ideolo- gicznie nacechowanych gatunków, atakowali niektóre elementy leżące u podstaw 1 J. Baudrillard, Ameryka, przeł. R. Lis [sic!], Warszawa 1998, s. -

Convert Finding Aid To

An Inventory of the Collection at the Harry Ransom Center Descriptive Summary Creator: Weiner, Matthew, 1965- Title: Mad Men Collection Dates: 1912-2016 (bulk 1957-2014) Extent: 189 document boxes, 4 serial boxes, 31 oversize boxes (osb) (79.38 linear feet), 9 oversize folders (osf), 1 bound volume (bv), 99 computer disks Abstract: The Mad Men Collection documents the work of Mad Men creator Matthew Weiner and his writing and production team behind the scenes of the acclaimed television drama. Scripts, production materials, and publicity materials date from 2001 to 2016, while clippings, magazines, and other materials collected for research primarily date from the late 1950s to the early 1970s. Also present in the collection are four boxes of scripts and production materials from Weiner’s 2013 feature film Are You Here. Call Number: Film Collection FI-05249 Language: English, with publicity materials in French, German, Italian, Japanese, Spanish, and Swedish Access: Open for research. Researchers must create an online Research Account and agree to the Materials Use Policy before using archival materials. To request access to electronic files, please email Reference. Documents containing personal information are restricted due to privacy concerns during the lifetime of individuals mentioned in the documents; in many instances, these documents have been replaced with redacted photocopies. Use Policies: Ransom Center collections may contain material with sensitive or confidential information that is protected under federal or state right -

Mad Men As a Sonic Symptomatology of Consumer Capitalism by Marc Brooks*

Marc Brooks – Mad Men Page 1 Mad Men as a Sonic Symptomatology of Consumer Capitalism By Marc Brooks* AT THE HEIGHT OF THE BRITISH INVASION in 1966, after a client insists on having a band that at least sounds like the Beatles in their advert, Don Draper wonders: ‘When did music become so important?’1 Don is talking about youth culture, from which he feels increasingly distant. But music also became ‘so important’ in television advertising during the 1960s, when Mad Men (Matthew Weiner, AMC 2007–15) is set, because advertisers were relying ever more on affect.2 Don—the implausibly handsome, successful, and yet curiously dissatisfied creative director of a middling Madison Avenue advertising company around whom the show revolves—sums up the situation nicely to his young protégée Peggy Olsen: ‘You are the product. You feeling something. That’s what sells’.3 Music, advertisers came to realize, is particularly good at making viewers feel things.4 Unlike The Sopranos (1999–2007), The Wire (2002–08), and Battlestar Galactica (2004–09), which are generally held to deserve the epithet ‘quality TV’, Mad Men splits critics down the middle.5 One of the main complaints is that it assumes the form of its subject matter; it offers *University of Vienna. Email: [email protected]. This article is based on talks given at the ‘Intertextuality in Music since 1900’ conference at the Universidade Nova de Lisboa, 6-7 March 2015, and at the 15th Annual Conference of the Society for Musicology in Ireland at Queen’s University Belfast, 16-18 June 2017. -

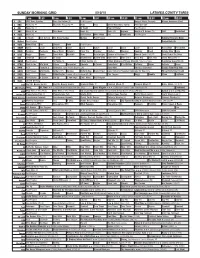

Sunday Morning Grid 5/10/15 Latimes.Com/Tv Times

SUNDAY MORNING GRID 5/10/15 LATIMES.COM/TV TIMES 7 am 7:30 8 am 8:30 9 am 9:30 10 am 10:30 11 am 11:30 12 pm 12:30 2 CBS CBS News Sunday Face the Nation (N) Paid Program Gospel Music Presents African American Short 4 NBC News (N) Å Meet the Press (N) Å News Paid World/Adventure Sports PGA Tour Golf 5 CW News (N) Å In Touch Hour Of Power Paid Program 7 ABC News (N) Å This Week News (N) News (N) Explore World of X Games (N) NBA Basketball 9 KCAL News (N) Joel Osteen Mike Webb Paid Woodlands Paid Program 11 FOX In Touch Joel Osteen Fox News Sunday Midday Paid Program National Treasure: Book 13 MyNet Paid Program Desperately Sk. 18 KSCI Breast Red Paid Church Faith Paid Program 22 KWHY Cosas Local Jesucristo Local Local Gebel Local Local Local Local RescueBot RescueBot 24 KVCR Painting Dewberry Joy of Paint Wyland’s Paint This Painting Kitchen Mexican Cooking Fresh Simply Ming Lidia 28 KCET Raggs Space Travel-Kids Biz Kid$ News Asia Insight Echoes of Creation Å Sacred Earth (TVG) Å Dudu Fisher The Voice 30 ION Jeremiah Youssef In Touch Bucket-Dino Bucket-Dino Doki (TVY7) Doki (TVY7) Dive, Olly Dive, Olly Ghost Whisperer Å 34 KMEX Paid Program Al Punto (N) Fútbol Central (N) Fútbol Mexicano Primera División: Toluca vs Tigres República Deportiva (N) 40 KTBN Walk in the Win Walk Prince Carpenter Liberate In Touch PowerPoint It Is Written Pathway Super Kelinda Jesse 46 KFTR Paid Fórmula 1 Fórmula 1 Gran Premio España.