Beakers of the Upper Thames District

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Elms Road, Cassington, Witney, Oxfordshire, OX29 4DR Guide Price

Elms Road, Cassington, Witney, Oxfordshire, OX29 4DR A semi-detached House with 3 Bedrooms and a good size rear garden. Scope for extension possibilities and is offered with no onward chain. Guide Price £325,000 VIEWING By prior appointment through Abbey Properties. Contact the Eynsham office on 01865 880697. DIRECTIONS From the Eynsham roundabout proceed east on the A40 towards Oxford and after a short distance turn left at the traffic lights into the village of Cassington. Continue through the village centre, past the Red Lion Public House and Elms Road will be found a short distance afterwards on your left hand side. DESCRIPTION A well-proportioned 3 Bedroom semi-detached House dating from the 1950's with potential to extend and a larger than average garden overlooking allotment land at the rear. The property has been let for some years and as a result has been maintained and updated in parts with a refitted Kitchen and double glazing but there does remain some scope for further improvement and possible extension, subject to consents. The accommodation includes a double aspect Sitting Room, Dining/Playroom, Kitchen, Utility, a Rear Lobby with conversion possibilities, 3 Bedrooms and Bathroom. There is gas central heating, driveway parking at the front and a good sized rear garden enjoying an open aspect. Cassington is a very popular village lying just off the A40, 1 mile from Eynsham and in Bartholomew School catchment and some 5 miles west of Oxford. End of chain sale offering immediate vacant possession. LOCATION Cassington lies just north of the A40 and provides easy access to both Witney, Oxford, A34, A420 and the M40. -

Settlement Type

Design Guide 5 Settlement Type www.westoxon.gov.uk Design Guide 5: Settlement Type 2 www.westoxon.gov.uk Design Guide 5: Settlement Type 5.1 SETTLEMENT TYPE Others have an enclosed character with only limited views. Open spaces within settlements, The settlements in the District are covered greens, squares, gardens – even wide streets – by Local Plan policies which describe the contribute significantly to the unique form and circumstances in which any development will be character of that settlement. permitted. Most new development will occur in sustainable locations within the towns and Where development is permitted, the character larger villages where a wide range of facilities and and context of the site must be carefully services is already available. considered before design proposals are developed. Fundamental to successfully incorporating change, Settlement character is determined by a complex or integrating new development into an existing series of interactions between it and the landscape settlement, is a comprehensive understanding of in which it is set – including processes of growth the qualities that make each settlement distinctive. or decline through history, patterns of change in the local economy and design or development The following pages represent an analysis of decisions by landowners and residents. existing settlements in the District, looking at the pattern and topographic location of settlements; As a result, the settlements of West Oxfordshire as well as outlining the chief characteristics of all vary greatly in terms of settlement pattern, scale, of the settlements in the District (NB see 5.4 for spaces and building types. Some villages have a guidance on the application of this analysis). -

Tithe Barn Jericho Farm • Near Cassington • Oxfordshire • OX29 4SZ a Spacious and Exceptional Quality Conversion to Create Wonderful Living Space

Tithe Barn Jericho Farm • Near Cassington • Oxfordshire • OX29 4SZ A spacious and exceptional quality conversion to create wonderful living space Oxford City Centre 6 miles, Oxford Parkway 4 miles (London, Marylebone from 56 minutes), Hanborough Station 3 miles (London, Paddington from 66 minutes), Woodstock 4.5 miles, Witney 7 miles, M40 9/12 miles. (Distances & times approximate) n Entrance hall, drawing room, sitting room, large study kitchen/dining room, cloakroom, utility room, boiler room, master bedroom with en suite shower room, further 3 bedrooms and family bathroom n Double garage, attractive south facing garden n In all about 0.5 acres Directions Leave Oxford on the A44 northwards, towards Woodstock. At the roundabout by The Turnpike public house, turn left signposted Yarnton. Continue through the village towards Cassington and then, on entering Worton, turn right at the sign to Jericho Farm Barns, and the entrance to Tithe Barn will be will be seen on the right after a short distance. Situation Worton is a small hamlet situated just to the east of Cassington with easy access to the A40. Within Worton is an organic farm shop and cafe that is open at weekends. Cassington has two public houses, a newsagent, garden centre, village hall and primary school. Eynsham and Woodstock offer secondary schooling, shops and other amenities. The nearby historic town of Woodstock provides a good range of shops, banks and restaurants, as well as offering the World Heritage landscaped parkland of Blenheim Palace for relaxation and walking. There are three further bedrooms, family bathroom, deep eaves storage and a box room. -

Excavations at Vicarage Field, Stanton Harcourt, 1951

Excavations at Vicarage Field, Stanton Harcourt, 1951 WITH AN ApPENDIX ON SECONDARY NEOLITmC WARES IN THE OXFORD REGION By NICHOLAS THOMAS THE SITE ICARAGE Field (FIG. I) lies less than half a mile from the centre of V Stanton Harcourt village, on the road westward to Beard Mill. It is situated on one of the gravel terraces of the upper Thames. A little to the west the river Windrush flows gently southwards to meet the Thames below Standlake. About four miles north-east another tributary, the Evenlode, runs into the Thames wlllch itself curves north, about Northmoor, past Stanton Harcourt and Eynsham to meet it. The land between this loop of the Thames and the smaller channels of the Windrush and Evenlode is flat and low-lying; but the gravel subsoil allows excellent drainage so that in early times, whatever their culture or occupation, people were encouraged to settle there.' Vicarage Field and the triangular field south of the road from Stanton Harcourt to Beard Mill enclose a large group of sites of different periods. The latter field was destroyed in 1944-45, after Mr. D. N. Riley had examined the larger ring-ditch in it and Mr. R. J. C. Atkinson the smaller.' Gravel-working also began in Vicarage Field in 1944, at which time Mrs. A. Williams was able to examine part of the area that was threatened. During September, 1951,' it became necessary to restart excavations in Vicarage Field when the gravel-pit of Messrs. Ivor Partridge & Sons (Beg broke) Ltd. was suddenly extended westward, involving a further two acres of ground. -

Burford Primary School Priory Lane, Burford, Oxon, OX18 4SG Key

Burford Primary School Priory Lane, Burford, Oxon, OX18 4SG Tel: 01993 822159 Fax: 01993 822792 Email: [email protected] Head Teacher – Mrs Jenny Dyer School website: www.burford-pri.oxon.sch.uk ‘Respect, Aspire, Achieve’ Key Admission Dates for Reception in 2019 Burford Primary is an academy with the Oxford Diocesan Schools Trust. The Governors have made every effort to ensure these admission arrangements comply with the School Admissions Code 2014 and all relevant legislation including that on infant class sizes and equal opportunities. Our policy guidelines follow those of Oxfordshire County Council and the administration of admission arrangements, including any appeals, for Reception to Year 6 are dealt with by their Admission Team and full information can be found on their website at https://www.oxfordshire.gov.uk/residents/schools/starting-school/infant- and-primary-school Our catchment area includes the communities of Burford, Asthall, Bradwell Grove, Fulbrook, Shilton, Signet Taynton, Westwell and Widford and the following key dates relate to Reception entry in September 2019, for children born from 1 September 2014 to 31 August 2015, inclusive. Key dates & deadlines ‘Starting School’ available for viewing online September 2018 https://www.oxfordshire.gov.uk/residents/schools/starting-school/infant-and- primary-school Online and paper applications accepted from this date. 25 October 2018 ‘Starting School’ information available on request from schools and Oxfordshire County Council 15 January 2019 National closing date for on-time applications for primary school National Allocation Day: letters are sent by second class post and emails sent to 16 April 2019 those who applied online, detailing the offer of a school place September 2019 Start of academic year for above phases . -

Oxfordshire Archdeacon's Marriage Bonds

Oxfordshire Archdeacon’s Marriage Bond Index - 1634 - 1849 Sorted by Bride’s Parish Year Groom Parish Bride Parish 1635 Gerrard, Ralph --- Eustace, Bridget --- 1635 Saunders, William Caversham Payne, Judith --- 1635 Lydeat, Christopher Alkerton Micolls, Elizabeth --- 1636 Hilton, Robert Bloxham Cook, Mabell --- 1665 Styles, William Whatley Small, Simmelline --- 1674 Fletcher, Theodore Goddington Merry, Alice --- 1680 Jemmett, John Rotherfield Pepper Todmartin, Anne --- 1682 Foster, Daniel --- Anstey, Frances --- 1682 (Blank), Abraham --- Devinton, Mary --- 1683 Hatherill, Anthony --- Matthews, Jane --- 1684 Davis, Henry --- Gomme, Grace --- 1684 Turtle, John --- Gorroway, Joice --- 1688 Yates, Thos Stokenchurch White, Bridgett --- 1688 Tripp, Thos Chinnor Deane, Alice --- 1688 Putress, Ricd Stokenchurch Smith, Dennis --- 1692 Tanner, Wm Kettilton Hand, Alice --- 1692 Whadcocke, Deverey [?] Burrough, War Carter, Elizth --- 1692 Brotherton, Wm Oxford Hicks, Elizth --- 1694 Harwell, Isaac Islip Dagley, Mary --- 1694 Dutton, John Ibston, Bucks White, Elizth --- 1695 Wilkins, Wm Dadington Whetton, Ann --- 1695 Hanwell, Wm Clifton Hawten, Sarah --- 1696 Stilgoe, James Dadington Lane, Frances --- 1696 Crosse, Ralph Dadington Makepeace, Hannah --- 1696 Coleman, Thos Little Barford Clifford, Denis --- 1696 Colly, Robt Fritwell Kilby, Elizth --- 1696 Jordan, Thos Hayford Merry, Mary --- 1696 Barret, Chas Dadington Hestler, Cathe --- 1696 French, Nathl Dadington Byshop, Mary --- Oxfordshire Archdeacon’s Marriage Bond Index - 1634 - 1849 Sorted by -

Read the Report!

JOHN MOOREHERITAGE SERVICES AN ARCHAEOLOGICAL EXCAVATION AND RECORDING ACTION AT LAND ADJACENT TO FARWAYS, YARNTON ROAD, CASSINGTON, OXFORDSHIRE NGR SP 4553 1122 On behalf of Blenheim Palace APRIL 2015 John Moore HERITAGE SERVICES Land adj. to Farways, Yarnton Road, Cassington, Oxon. CAYR 13 Archaeological Excavation Report REPORT FOR Blenhiem Palace Estate Office Woodstock Oxfordshire OX20 1PP PREPARED BY Andrej Čelovský, with contributions from David Gilbert, Linzi Harvey, Claire Ingrem, Frances Raymon, and Jane Timby EDITED BY David Gilbert APPROVED BY John Moore ILLUSTRATION BY Autumn Robson, Roy Entwistle, and Andrej Čelovský FIELDWORK 18th Febuery to 22nd May 2014 Paul Blockley, Andrej Čelovský, Gavin Davis, Simona Denis, Sam Pamment, and Tom Rose-Jones REPORT ISSUED 14th April 2015 ENQUIRES TO John Moore Heritage Services Hill View Woodperry Road Beckley Oxfordshire OX3 9UZ Tel/Fax 01865 358300 Email: [email protected] Site Code CAYR 13 JMHS Project No: 2938 Archive Location The archive is currently held at John Moore Heritage Services and will be deposited with Oxfordhsire County Museums Service with accession code 2013.147 John Moore HERITAGE SERVICES Land adj. to Farways, Yarnton Road, Cassington, Oxon. CAYR 13 Archaeological Excavation Report CONTENTS Page Summary i 1 INTRODUCTION 1 1.1 Site Location 1 1.2 Planning Background 1 1.3 Archaeological Background 1 2 AIMS OF THE INVESTIGATION 3 3 STRATEGY 3 3.1 Research Design 3 3.2 Methodology 3 4 RESULTS 6 4.1 Field Results 6 4.2 Bronze Age 7 4.3 Iron Age 20 4.4 Roman -

Oxfordshire Early Years Provider Directory

Oxfordshire Early Years Provider Directory The following list gives you contact details of providers currently registered to offer the nursery education funding entitlement in your local area. Please contact these providers direct to enquire if they have places available, and for more information on session times and lengths. Private, voluntary and independent providers will also be able to tell you how they operate the entitlement, and give you more information about any additional costs over and above the basic grant entitlement of 15 hours per week. Admissions for Local Authority (LA) school and nursery places for three and four year olds are handled by the nursery or school. Nursery Education Funding Team Contact information for general queries relating to the entitlement: Telephone 01865 815765 Email [email protected] Oxfordshire Early Years Provider Directory Name Telephone Address Independent Windrush Valley School 01993831793 The Green, 2 London Lane, Ascott-under-wychwood, Chipping Norton, OX7 6AN Oxfordshire Early Years Provider Directory Name Telephone Address LEA Nursery, Primary or Special School Wychwood Church of England 01993 830059 Milton Road, Shipton-under-Wychwood, Chipping Primary School Norton, OX7 6BD Woodstock Church of England 01993 812209 Shipton Road, Woodstock, OX20 1LL Primary School Wood Green School 01993 702355 Woodstock Road, Witney, OX28 1DX Witney Community Primary 01993 702388 Hailey Road, Witney, OX28 1HL School William Fletcher Primary School 01865 372301 RUTTEN LANE, YARNTON, KIDLINGTON, OX5 1LW West Witney Primary School 01993 706249 Edington Road, Witney, OX28 5FZ Tower Hill School 01993 702599 Moor Avenue, Witney, OX28 6NB The Marlborough Church of 01993 811431 Shipton Road, Woodstock, OX20 1LP England School The Henry Box School 01993 703955 Church Green, Witney, OX28 4AX The Blake CofE (Aided) Primary 01993 702840 Cogges Hill Road, Witney, OX28 3FR School The Batt CofE (A) Primary 01993 702392 Marlborough Lane, Witney, OX28 6DY School, Witney Tackley Church of England 01869 331327 42 ST. -

Oxfordshire Minerals and Waste Development Framework Mineral Site Nominations

Oxfordshire Minerals and Waste Development Framework Mineral Site Nominations Sand and Gravel Nominations Ref Site Name Location Nominator Grid Ref Nomination Details of Nomination Status SG-03 Land adj to Benson Wallingford Bell Cornwall LLP SU 610 919 Renewal New site for sand and Marina gravel extraction SG-04 Land at Mead Farm Yarnton Hanson Aggregates SP 480 113 Renewal Lateral extension to Cassington Quarry SG-05 Land to the East of Cassington Hanson Aggregates SP 485 108 Renewal Lateral extension to Cassington quarry Cassington quarry SG-08 Land at Lower Road Church Carter Jonas SP 433 121 Renewal Extension to Cassington Hanborough LLP/Hanson quarry Aggregates SG-09 Land north of Berinsfield D K Symes SU 599 973 Renewal New site for sand and Drayton St Leonard Associates gravel extraction and Berinsfield SG-11 Land east of Spring Caversham Lafarge Aggregates SU 753 768 Amended Extension of Caversham Lane, Sonning Eye Ltd Quarry (Caverhsam ‘C’) SG-12 Land South of Mapledurham Lafarge Aggregates SU 685 752 Renewal New site for sand and Chazey Wood Ltd gravel extraction SG-13 Land at Shillingford Shillingford Hanson Aggregates SU 605 930 Renewal New site for sand and gravel extraction SG-15 Dairy Farm Clanfireld Hanson Aggregates SP 302 014 Renewal New site for sand and gravel extraction SG-16 Land at Stonehouse Yarnton Hanson Aggregates SP 483 114 Renewal Extension to Cassington Farm, nprth east of quarry Cassington Quarry SG-17 Land at Culham Culham Hills Quarry SU 537 945 Renewal New site for sand and Products Ltd gravel extraction -

Nor'lye News Is Seeking a New Advertising Co-Ordinator Responsible for Managing All the Paid Adverts in the Nor'lye News

Nor’Lye News The monthly newsletter serving North Leigh, New Yatt, East End and Wilcote March 2020 – No. 560 Visit the Nor’Lye News website www.norlyenews.org.uk Dates for your diary: March Page Tuesday 3 rd History Society “Roman Silchester: The oldest public baths in Britain” 3 Rev Margaret Dixon, Turner Hall 7.30pm Friday 6 th (Also March 20th) Working Party on North Leigh Common – 10am start 6 Sunday 15 th Charity Darts Competition Masons Arms 2pm 10 Sunday 22nd Special Mothering Sunday Cafe Church Service North Leigh School 10am 2 Tuesday 24 th Gardening Society Spring Show, Quiz and Cheese and Wine Supper 4 Memorial Hall 7.30pm, (Staging of exhibits 7-7.30pm) Wednesday 18th Author Talk by Merilyn Davies #WhenIlostyou North Leigh Library 7pm 7 Friday 27th Harry St. John WODC Councillor Surgery Committee room NLMH 2-3pm 6 Sunday 29 th Charity Pub Quiz Masons Arms 8pm April st Wednesday 1 A.G.M. Friends of St Mary's in The Turner Hall,7.30 pm 9 nd Thursday 2 Easter Bingo Turner Hall 7pm 4 th Tuesday 7 History Society “600 years of Morris Dancing” by Michael Heaney, 3 Turner Hall 7.30pm North Leigh Cub Scout Packs In North Leigh we have two thriving Cub Scout Packs, consisting of boys and girls from 8 to 10 ½ years old. Over the past year the Cubs have taken part in a wide range of activities such as night hikes, camping, outdoor cooking, making bivouacs, playing team building games, paper pioneering, making & testing boats out of recycled materials, first aid, having a go on a golf range, crate stacking, abseiling and tackling a climbing wall, and the list goes on and on. -

New Discoveries of Neolithic Pottery in Oxfordshire

New Discoveries of Neolithic Pottery in Oxfordshire By E. T. LEEDS NDER the heading Early Man in the recently published Volume I of U the Victoria History of Oxfordshire (p. 242) some attention was paid to discoveries of Neolithic pottery within the county, naturally with particu lar reference to similar discoveries in adjacent counties. Much of the material there reviewed, consisting of old finds; like the fine bowls from the River Thames at Mongewell, stray sherds from Asthall, spoons from Swell, Gloucestershire, sherds from Buston Farm, Astrop, Northamptonshire, and the large mass of pottery from Abingdon, Berkshire, has already been fully published elsewhere, and references to the pertinent literature were given. Some notice was also taken of more recent discoveries at Cassington and Stanton Harcourt, with an illustration of one piece from each of those places. The scope of that publication however, did not permit of more than a summary account of these later dis coveries, and it has seemed desirable that they should be recorded in fuller detail, not only because the pottery in question is rare in occurrence anywhere, but also because it includes material which may have a distinct bearing on the history and development of Bronze Age ceramic in this country. Three classes of Neolithic pottery are, as is well known, now recognised: I. Neolithic A, or Windmill Hill, to give it its older title, a southern group, chiefly known from the Wiltshire site, near Avebury. To this belongs the material from the occupation-site at Abingdon, representing a secondary phase of its development, as recorded also from other sites, such as Hembury Fort, Devon, and Whitehawk Hill, Sussex. -

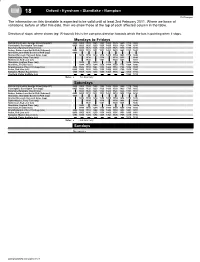

Timetable Book

18 Oxford - Eynsham - Standlake - Bampton RH Transport The information on this timetable is expected to be valid until at least 2nd February 2011. Where we know of variations, before or after this date, then we show these at the top of each affected column in the table. Direction of stops: where shown (eg: W-bound) this is the compass direction towards which the bus is pointing when it stops. Mondays to Fridays Oxford City Centre, George Street (Stop B1) 0820 1005 1105 1205 1305 1405 1505 1605 1715 1805 Cassington, Cassington Turn (opp) 0835 1020 1120 1220 1320 1420 1520 1628 1740 1830 Eynsham, Eynsham Church (o/s) 1026 1126 1226 1326 1426 1526 1638 1746 1836 Sutton, Sutton Lane Hail & Ride (S-bound) 0842 1031 1131 1231 1331 1431 1531 1643 1751 1841 Standlake, Standlake Business Park (opp) 0845 Stanton Harcourt, Harcourt Arms (opp) 1034 1134 1234 1334 1434 1534 1646 1754 1844 Bablockhythe, Ferry Turn (adj) 1138 1338 1538 1650 1848 Northmoor, Red Lion (o/s) 1141 1341 1541 1653 1851 Standlake, Heyford Close (adj) 1040 1240 1440 1800 1856s Standlake, The Bell (o/s) 1044 1150 1244 1350 1444 1550 1702 1804 1900 Brighthampton, Chervil Cottage (o/s) 0846 1046 1152 1246 1352 1446 1552 1704 1806 1902 Aston, Red Lion (o/s) 0850 1050 1156 1250 1356 1450 1556 1708 1810 1906 Bampton, Market Square (on) 0858 1058 1205 1258 1405 1458 1605 1820 1915 Clanfield, Carter Institute (o/s) 1824 1919 Notes: s - Set down only Saturdays Oxford City Centre, George Street (Stop B1) 0820 1005 1105 1205 1305 1405 1505 1605 1715 1805 Cassington, Cassington Turn (opp)