Fountain Creek, Colorado, 2007–2008, by Using Multiple Lines of Evidence

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Historic District and Map • Historic Subdistricts and Maps • Architectural Styles

City of Manitou Springs Historic District Design Guidelines CHAPTER 2 Historic Context • Historic District and Map • Historic Subdistricts and Maps • Architectural Styles Chapter 2: Historic Context City of Manitou Springs Historic District Design Guidelines Chapter 2: Historic Context City of Manitou Springs Historic District Design Guidelines Chapter 2: Historical Context This section describes the historical context of Manitou Springs as refl ected in its historic structures. A communi- ty history can be documented in a collection of names and dates carefully recorded in history books seldom read, or it can be seen everyday in the architecture of the past. Protecting and preserving that architectural heritage is one way we can celebrate the people and events that shaped our community and enhance the foundation for our future growth and development. Background Large Queen Anne Victorian hotels such as the Bark- er House and the Cliff House are visible reminders of Manitou’s heyday as a health resort. These grand buildings, although altered signifi cantly through ear- ly renovations, date back to the 1870s when Manitou Springs was founded by Dr. William Bell, an Eng- lish physician and business partner of General Wil- liam Palmer, the founder of Colorado Springs and the Denver and Rio Grande Railroad. Dr. Bell envi- sioned a European-style health resort built around the natural mineral springs with public parks, gardens, villas and elegant hotels. With this plan in mind, Manitou Springs’ fi rst hotel, the Manitou House, was constructed in 1872. Development during the 1870s -1880s was rapid and consisted primarily of frame construction. Although Manitou’s growth did not faithfully adhere to Dr. -

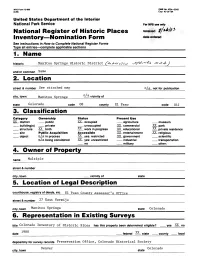

National Register of Historic Places Inventory Nomination Form

(11-78) United States Department of the Interior Heritage Conservation and Recreation Service National Register of Historic Places Inventory Nomination Form See instructions in How to Complete National Register Forms Type all entries complete applicable sections________________ 1. Name historic '-Multiple Resource Area W^Manitou Springs/ and/or common Same 2. Location street & number -Tn-.--w..^FITri-^7M1 Springs ^^ not for publication city, town Manitou Springs n/a.. vicinity of congressional district state Colorado code 08 county El Paso code 041 3. Classification Category Ownership Status Present Use district public x occupied agriculture x museum building(-S) private y unoccupied x commercial _x_park structure x b°th x work in progress x educational y private residence $ite Public Acquisition Accessible x entertainment x religious object n/a in process x yes: restricted x government scientific x multiple n/a being considered x yes: unrestricted industrial x transportation resource x no military Other: 4. Owner of Property name Multiple. See continuation sheets. street & number city, town n/a vicinity of state 5. Location of Legal Description courthouse, registry of deeds, etc. E1 pasp County Assessor . s o££ice street & number 27 East Vermijo city, town Colorado Springs state Colorado 6. Representation in Existing Surveys Colorado Preservation Office Survey has this property been determined elegible? yes no date i960 federal state county local depository for survey recordsColorado Preservation Office city, town Denver state 7. Description Condition Check one Check one _ 2L excellent deteriorated unaltered x original site _ x.good ruins x altered moved date _ x-fair unexnosed Describe the present and original (if known) physical appearance Survey Methodology The Multiple Resource Area of Manitou Springs nomination is based on a comprehensive survey of all standing structures within the city limits of the town. -

Rocky Mountains to the Golden Gate

XaOCATED one block from Grand Central Station, and on highest grade of land in the city. A Hotel of Superior Excellence, conducted on both the AMERICAN AND 40- TO 41 ~ STS. PARK AVE. NEW YORK. EUROPEAN PLANS. The water and ice used are vaporized and frozen, and free from disease germs. THE PATRONS OF THE MURRAY HILL HOTEL HAVE THEIR BAGGAGE TRANSFERRED TO AND FROM THE GRAND CENTRAL STATION f^ree; or cmarqe- TN addition to being favor- ite in Fall and Winter, it is most desirable, cool and delightful for Spring and Summer Visitors, located in the heart of New York City, at 5 th Avenue and 58th and 59th Streets, and overlook- ing Central Park and Plaza Square. A marvel of luxury and comfort. Convenient to places of amusement and stores. Fifth Avenue stages, cross-town and belt-line horse cars pass the doors. Terminal Station Sixth Avenue Elevated Road within half a block. THE HOTEL IS ABSOLUTELY FIRE-PROOF. Conducted on American and European plans. The water and ice used are vaporized and frozen on the premises, and certified to by Prof. Chas. F. Chandler as to purity. Summer rates. F. A. HAMMOKD. BEST LIN Chicago and St. Louis : ST. PAUL MINNEAPOLIS. OMAHA, LINCOLN. 1 • • DENVER,.-— CHEYENNE, DEADWOOD, BEST LINE from STYJOSEPH, KANSAS CITY. Chicago and St. Louis - TO ALL POINTS NORTHWEST WEST and SOUTHWEST mm mm. lions World’s Columbian Exposition. HALL AUTOMATIC ELECTRIC BLOCK SYSTEM ON THE ILLINOIS CENTRAL R.R. 7%FTER the most thorough investigation ever made into the subject of block signals THE ILLINOIS CENTRAL RAILROAD COMPANY HAS ADOPTED THE HALL SYSTEM OF AUTOMATIC ELECTRIC SIGNALS for the protection of their entire WORLD’S FAIR TRAFFIC on their eight tracks from CHICAGO to GRAND CROSSING, and four tracks from GRAND CROSSING to KENSINGTON. -

Implementation Plan

IMPLEMENTATION PLAN The Pikes Peak region will invest in outcome-driven activities that specifically meet the goals and priorities established in the Regional Transportation Plan. The RTP utilized qualitative and quantitative data gathered through citizen input, partner agency participation, technical analysis and needs assessment to identify the highest priority needs in which to direct funding. the plan. Funding preventive maintenance is crucial to maintaining a transpor- Recommended Management and Operations Strategies CHAPTER EIGHT tation system, including maintaining or rehabilitating road surface, and replac- Transportation System Management and Operations strategies will be consid- ing or repairing bridges, as well as maintaining bicycle and pedestrian facilities unicipalities that own components of the transpor- ered and analyzed in connection with all investments in the plan either as indi- and public transportation. tation system will implement the vast majority of vidual “stand-alone” projects or as part of another transportation project. improvements to the regional transportation sys- Even with a design life of 75 years, there are many bridges that currently, or • Implement the Colorado Department of Transportation’s Intelligent Trans- tem in the next 25 years. To assure that the trans- will in the next 25 years, need rehabilitation. The infrastructure maintenance portation Systems Strategic Plan and regional ITS architecture to enhance portation system meets existing and future travel needs of the goal was established to improve all deficient structures as soon as possible incident management program effectiveness. and to provide adequate funding to inspect, maintain, rehabilitate, or replace Pikes Peak region, the Moving Forward 2040 Regional Transpor- • Continue development of coordinated traffic-responsive signal systems. -

Thesis Submitted to The

GUIDE TO NAVAGATING THIS DOCUMENT Key words in this document are linked to other pages, tables, figures, or plates. Clicking on blue highlighted words in the body of the document with the mouse cursor will cause the screen to automatically go to a linked page. For example, if you click on the word CONTENTS the screen will go to the start of the table of contents of this document. To get back to where you started, click on the right mouse button and then click on “Go Back” (try it). Alternately, clicking on any heading in the body of the document will bring you back to the place in the table of contents were the heading is listed. Clicking on red text in the body of the document will take you to a related table, figure, or plate. For example, clicking on Figure 1 will take you to Figure 1. Clicking on the right button and then clicking on “Go Back” will take you back. Use the “Help” menu of Acrobat Reader for more information, such as searching for specific words in the text or changing the scale of the figures and plates. Good Luck. GENESIS OF CAVE OF THE WINDS, MANITOU SPRINGS, COLORADO By Fredrick George Luiszer B.A., University of Colorado, 1987 A thesis submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate School of the University of Colorado in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of Geological Sciences 1997 This Thesis entitled: Genesis of Cave of the Winds, Manitou Springs, Colorado written by Fredrick George Luiszer has been approved for the Department of Geological Sciences _____________________________ Chair of Committee ______________________________ Committee member Date________________ The final copy of this thesis has been examined by the signators, and we find that both content and the form meet acceptable presentation standards of scholarly work in the above mentioned discipline. -

City of Manitou Springs Community Wildfire Protection Plan

City of Manitou Springs Community Wildfire Protection Plan City of Manitou Springs Community Wildfire Protection Plan Recommendation and Approval Recommended by: Bobby White, Wildland Fire Coordinator Date Manitou Springs Fire Department Approved by: Ken Jaray, Mayor Date City of Manitou Springs Dave Root, District Forester Date Colorado State Forest Service John K. Forsett, Fire Chief Date City of Manitou Springs Roy C. Chaney, Interim City Administrator Date City of Manitou Springs ii Table of Contents: Introduction ........................................................................................................................................... 1 Fire Adapted vs. Mitigation ................................................................................................................... 1 Area Description ................................................................................................................................... 4 Topography ...................................................................................................................................... 4 Fuels .................................................................................................................................................. 6 Weather ............................................................................................................................................ 7 Manitou Springs Fire Department ........................................................................................................ 7 Wildfire -

National Register of Historic Places M^ Inventory—Nomination Form Date Entered 1. Name 2. Location 3. Classification 4. Owner

NFS Form 10-900 OMB No. 1024-0018 (3-82) Exp. 10-31-84 United States Department off the Interior National Park Service For NPS use only National Register of Historic Places m^ Inventory—Nomination Form date entered See instructions in How to Complete National Register Forms Type all entries—complete applicable sections .__________________________ 1. Name historic Manitou Springs Historic District J and/or common Same 2. Location street & number See attached map n/a not for publication city, town Manitou Springs vicinity of state Colorado code 08 county El Paso code 041 3. Classification Category Ownership Status Present Use XX_ district public XX occupied agriculture museum building(s) private unoccupied J£X_ commercial XX park Structure XX both XX work in progress XX educational XX private residence site Public Acquisition Accessible XX entertainment XX religious object n/a in process XX yes: restricted XX government scientific n/a being considered XX yes: unrestricted industrial transportation no military other: 4. Owner of Property name Multiple street & number city, town vicinity of state 5. Location of Legal Description courthouse, registry of deeds, etc. El Paso County Assessor f s Office street & number 2 ? East Vermijo city, town Manitou Springs state Colorado 6. Representation in Existing Surveys title Colorado Inventory of Historic Sites has this property been determined eligible? yes XX no 1980 date federal state county local depository for survey records Preservation Office, Colorado Historical Society Denver Colorado city, town state 7. Description Condition Check one Check one XX excellent deteriorated unaltered XX original site JSXgood ruins XX altered moved date J^fair unexposed Describe the present and original (iff known) physical appearance The Manitou Springs Historic District is composed of 1001 buildings, constituting the historic core of the town. -

J Manitou Avenue Master Plan R Manitou Springs, Colorado ( I R ( L

r r I ( r ~--_.J Manitou Avenue Master Plan r Manitou Springs, Colorado ( I r ( l . O[ [ . r r r Prepared By: THK Associates, Inc. in association with ( P JF & Associates Janurary 23, 1998 'l City of Manitou Springs The Avenue Project Summary Sheet In April, 1995, the City began discussions regarding what role it could play in enhancing Downtown Manitou Springs for citizens, businesses and visitors. These discussions resulted in a Master Plan for utility, pedestrian, safety, and esthetics improvements. The Master Plan process was begun in 1997 with the assistance ofplanning consultants, THK and a steering committee made up ofover 20 citizens, Downtown business persons, Chamber ofCommerce representation and City Staff. During 1997, eleven meetings were held between the steering committee and the consultants on the various options for improving Downtown. A wide range ofcitizen and visitor input was solicited through a survey which was done during the summer. Also, a newsletter publication was sent twice to every water bill customer in Manitou Springs. All the steering committee meetings were open to the public, and many were attended by interested persons outside the committee, however eight meetings particularly emphasized public participation to obtain feedback, present the consultants' options for improvements and, subsequently, the recommendations ofthe steering committee. A week long "Design Charette" was held in April. The Steering Committee manned a Project Office on Ruxton Avenue during this week to allow additional opportunities for individuals to review the plans, speak with Committee members and give their input. During the Master Plan process the Steering Committee and Consultants also recommended thatthe project be expanded to study the entire length of Manitou Avenue and the business area of Ruxton Avenue. -

Historic Context

City of Manitou Springs Historic District Design Guidelines CHAPTER 2 Historic Context • Historic District and Map • Historic Subdistricts and Maps • Architectural Styles Chapter 2: Historic Context City of Manitou Springs Historic District Design Guidelines Chapter 2: Historic Context City of Manitou Springs Historic District Design Guidelines Chapter 2: Historical Context This section describes the historical context of Manitou Springs as refl ected in its historic structures. A communi- ty history can be documented in a collection of names and dates carefully recorded in history books seldom read, or it can be seen everyday in the architecture of the past. Protecting and preserving that architectural heritage is one way we can celebrate the people and events that shaped our community and enhance the foundation for our future growth and development. Background Large Queen Anne Victorian hotels such as the Bark- er House and the Cliff House are visible reminders of Manitou’s heyday as a health resort. These grand buildings, although altered signifi cantly through ear- ly renovations, date back to the 1870s when Manitou Springs was founded by Dr. William Bell, an Eng- lish physician and business partner of General Wil- liam Palmer, the founder of Colorado Springs and the Denver and Rio Grande Railroad. Dr. Bell envi- sioned a European-style health resort built around the natural mineral springs with public parks, gardens, villas and elegant hotels. With this plan in mind, Manitou Springs’ fi rst hotel, the Manitou House, was constructed in 1872. Development during the 1870s -1880s was rapid and consisted primarily of frame construction. Although Manitou’s growth did not faithfully adhere to Dr.