Fall Line Magnolia Bogs of the Mid-Atlantic Region

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Neighborwoods Right Plant, Right Place Plant Selection Guide

“Right Plant, Right Place” Plant Selection Guide Compiled by Samuel Kelleher, ASLA April 2014 - Shrubs - Sweet Shrub - Calycanthus floridus Description: Deciduous shrub; Native; leaves opposite, simple, smooth margined, oblong; flowers axillary, with many brown-maroon, strap-like petals, aromatic; brown seeds enclosed in an elongated, fibrous sac. Sometimes called “Sweet Bubba” or “Sweet Bubby”. Height: 6-9 ft. Width: 6-12 ft. Exposure: Sun to partial shade; range of soil types Sasanqua Camellia - Camellia sasanqua Comment: Evergreen. Drought tolerant Height: 6-10 ft. Width: 5-7 ft. Flower: 2-3 in. single or double white, pink or red flowers in fall Site: Sun to partial shade; prefers acidic, moist, well-drained soil high in organic matter Yaupon Holly - Ilex vomitoria Description: Evergreen shrub or small tree; Native; leaves alternate, simple, elliptical, shallowly toothed; flowers axillary, small, white; fruit a red or rarely yellow berry Height: 15-20 ft. (if allowed to grow without heavy pruning) Width: 10-20 ft. Site: Sun to partial shade; tolerates a range of soil types (dry, moist) Loropetalum ‘ZhuZhou’-Loropetalum chinense ‘ZhuZhou’ Description: Evergreen; It has a loose, slightly open habit and a roughly rounded to vase- shaped form with a medium-fine texture. Height: 10-15 ft. Width: 10-15ft. Site: Preferred growing conditions include sun to partial shade (especially afternoon shade) and moist, well-drained, acidic soil with plenty of organic matter Japanese Ternstroemia - Ternstroemia gymnanthera Comment: Evergreen; Salt spray tolerant; often sold as Cleyera japonica; can be severely pruned. Form is upright oval to rounded; densely branched. Height: 8-10 ft. Width: 5-6 ft. -

Indiana's Native Magnolias

FNR-238 Purdue University Forestry and Natural Resources Know your Trees Series Indiana’s Native Magnolias Sally S. Weeks, Dendrologist Department of Forestry and Natural Resources Purdue University, West Lafayette, IN 47907 This publication is available in color at http://www.ces.purdue.edu/extmedia/fnr.htm Introduction When most Midwesterners think of a magnolia, images of the grand, evergreen southern magnolia (Magnolia grandiflora) (Figure 1) usually come to mind. Even those familiar with magnolias tend to think of them as occurring only in the South, where a more moderate climate prevails. Seven species do indeed thrive, especially in the southern Appalachian Mountains. But how many Hoosiers know that there are two native species Figure 2. Cucumber magnolia when planted will grow well throughout Indiana. In Charles Deam’s Trees of Indiana, the author reports “it doubtless occurred in all or nearly all of the counties in southern Indiana south of a line drawn from Franklin to Knox counties.” It was mainly found as a scattered, woodland tree and considered very local. Today, it is known to occur in only three small native populations and is listed as State Endangered Figure 1. Southern magnolia by the Division of Nature Preserves within Indiana’s Department of Natural Resources. found in Indiana? Very few, I suspect. No native As the common name suggests, the immature magnolias occur further west than eastern Texas, fruits are green and resemble a cucumber so we “easterners” are uniquely blessed with the (Figure 3). Pioneers added the seeds to whisky presence of these beautiful flowering trees. to make bitters, a supposed remedy for many Indiana’s most “abundant” species, cucumber ailments. -

Identification of Milkweeds (Asclepias, Family Apocynaceae) in Texas

Identification of Milkweeds (Asclepias, Family Apocynaceae) in Texas Texas milkweed (Asclepias texana), courtesy Bill Carr Compiled by Jason Singhurst and Ben Hutchins [email protected] [email protected] Texas Parks and Wildlife Department Austin, Texas and Walter C. Holmes [email protected] Department of Biology Baylor University Waco, Texas Identification of Milkweeds (Asclepias, Family Apocynaceae) in Texas Created in partnership with the Lady Bird Johnson Wildflower Center Design and layout by Elishea Smith Compiled by Jason Singhurst and Ben Hutchins [email protected] [email protected] Texas Parks and Wildlife Department Austin, Texas and Walter C. Holmes [email protected] Department of Biology Baylor University Waco, Texas Introduction This document has been produced to serve as a quick guide to the identification of milkweeds (Asclepias spp.) in Texas. For the species listed in Table 1 below, basic information such as range (in this case county distribution), habitat, and key identification characteristics accompany a photograph of each species. This information comes from a variety of sources that includes the Manual of the Vascular Flora of Texas, Biota of North America Project, knowledge of the authors, and various other publications (cited in the text). All photographs are used with permission and are fully credited to the copyright holder and/or originator. Other items, but in particular scientific publications, traditionally do not require permissions, but only citations to the author(s) if used for scientific and/or nonprofit purposes. Names, both common and scientific, follow those in USDA NRCS (2015). When identifying milkweeds in the field, attention should be focused on the distinguishing characteristics listed for each species. -

Physiological and Chemical Studies Upon the Milkweed (Asclepias Syriaca L) Fisk Gerhardt Iowa State College

Iowa State University Capstones, Theses and Retrospective Theses and Dissertations Dissertations 1928 Physiological and chemical studies upon the milkweed (Asclepias syriaca L) Fisk Gerhardt Iowa State College Follow this and additional works at: https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/rtd Part of the Agricultural Science Commons, Agriculture Commons, and the Plant Biology Commons Recommended Citation Gerhardt, Fisk, "Physiological and chemical studies upon the milkweed (Asclepias syriaca L)" (1928). Retrospective Theses and Dissertations. 14748. https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/rtd/14748 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Iowa State University Capstones, Theses and Dissertations at Iowa State University Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Retrospective Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Iowa State University Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has been reproduced from the microfilm master. UMl films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from any type of computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMl a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are reproduced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand comer and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overiaps. -

Glacial Lake Albany Butterfly Milkweed Plant Release Notice

UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF AGRICULTURE NATURAL RESOURCES CONSERVATION SERVICE BIG FLATS, NEW YORK AND ALBANY PINE BUSH PRESERVE COMMISSION ALBANY, NEW YORK AND THE NATURE CONSERVANCY EASTERN NEW YORK CHAPTER TROY, NEW YORK AND NEW YORK STATE DEPARTMENT OF ENVIRONMENTAL CONSERVATION ALBANY, NEW YORK NOTICE OF RELEASE OF GLACIAL LAKE ALBANY GERMPLASM BUTTERFLY MILKWEED The Albany Pine Bush Preserve Commission, U.S. Department of Agriculture, Natural Resources Conservation Service, The Nature Conservancy, and the New York State Department of Environmental Conservation, announce the release of a source-identified ecotype of Butterfly milkweed (Asclepias tuberosa L.). As a source identified release, this plant will be referred to as Glacial Lake Albany Germplasm butterfly milkweed, to document its original location. It has been assigned the NRCS accession number, 9051776. This alternative release procedure is justified because there is an immediate need for a source of local ecotype of butterfly milkweed. Plant material of this specific ecotype is needed for ecosystem and endangered species habitat restoration in the Pine Barrens of Glacial Lake Albany. The inland pitch pine - scrub oak barrens of Glacial Lake Albany are a globally rare ecosystem and provide habitat for 20 rare species, including the federally endangered Karner blue butterfly (Lycaeides melissa samuelis). The potential for immediate use is high and the commercial potential beyond Glacial Lake Albany is probably high. Collection Site Information: Stands are located within Glacial Lake Albany, from Albany, New York to Glens Falls, New York, and generally within the Albany Pine Bush Preserve, just west of Albany, New York. The elevation within the Pine Barrens is approximately 300 feet, containing a savanna-like ecosystem with sandy soils wind- swept into dunes, following the last glacial period. -

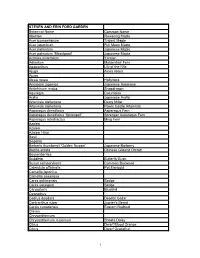

STEVEN and ERIN FORD GARDEN Botanical Name Common Name

STEVEN AND ERIN FORD GARDEN Botanical Name Common Name Abutilon Flowering Maple Acer buergerianum Trident Maple Acer japonicum Full Moon Maple Acer palmatum Japanese Maple Acer palmatum 'Bloodgood' Japanese Maple Achillea millefolium Yarrow Adiantum Maidenhair Fern Agapanthus Lily of the Nile Ajuga Alcea rosea Ajuga Alcea rosea Hollyhock Anemone japonica Japanese Anemone Antirrhinum majus Snapdragon Aquilegia Columbine Aralia Japanese Aralia Artemisia stelleriana Dusty Miller Artemisia stelleriana Powis Castle Artemisia Asparagus densiflorus Asparagus Fern Asparagus densiflorus 'Sprengeri' Sprenger Asparagus Fern Asparagus retrofractus Ming Fern Azalea Azalea Azalea 'Hino' Basil Begonia Berberis thumbergii 'Golden Nugget' Japanese Barberry Bletilla striata Chinese Ground Orchid Boysenberries Buddleja Butterfly Bush Buxus sempervirens Common Boxwood Calendula officinalis Pot Marigold Camellia japonica Camellia sasanqua Carex oshimensis Sedge Carex variegata Sedge Caryopteris Bluebird Ceanothus Cedrus deodara Deodar Cedar Centranthus ruber Jupiter's Beard Cercis canadensis Eastern Rudbud Chives Chrysanthemum Chrysanthemum maximum Shasta Daisy Citrus Dwarf Blood Orange Citrus Dwarf Grapefruit 1 Citrus Dwarf Tangerine Citrus Navel Orange Citrus Variegated Lemon Clematis Cornus Dogwood Cornus kousa Kousa Dogwood Cornus stolonifera Redtwig Dogwood Cotinus Smoke Tree Cryptomeria japonica Japanese Cryptomeria Cyathea cooperi Australian Tree Fern Cyclamen Delphinium Dianella tasmanica 'Yellow Stripe' Flax Lily Dianthus Pink Dianthus barbatus Sweet -

American Forests National Big Tree Program Species Without Champions

American Forests National Big Tree Program Champion trees are the superstars of their species — and there are more than 700 of them in our national register. Each champion is the result of a lucky combination: growing in a spot protected by the landscape or by people who have cared about and for it, good soil, the right amount of water, and resilience to the elements, surviving storms, disease and pests. American Forests National Big Tree Program was founded to honor these trees. Since 1940, we have kept the only national register of champion trees (http://www.americanforests.org/explore- forests/americas-biggest-trees/champion-trees-national-register/) Champion trees are found by people just like you — school teachers, kids fascinated by science, tree lovers of all ages and even arborists for whom a fun day off is measuring the biggest tree they can find. You, too, can become a big tree hunter and compete to find new champions. Species without Champions (March, 2018) Gold rows indict species that have Idaho State Champions but the nominations are too old to be submitted for National Champion status. Scientific Name Species Common Name Abies lasiocarpa FIR Subalpine Acacia macracantha ACACIA Long-spine Acacia roemeriana CATCLAW Roemer Acer grandidentatum MAPLE Canyon or bigtooth maple Acer nigrum MAPLE Black Acer platanoides MAPLE Norway Acer saccharinum MAPLE Silver Aesculus pavia BUCKEYE Red Aesculus sylvatica BUCKEYE Painted Ailanthus altissima AILANTHUS Tree-of-heaven Albizia julibrissin SILKTREE Mimosa Albizia lebbek LEBBEK Lebbek -

Magnolia 'Galaxy'

Magnolia ‘Galaxy’ The National Arboretum presents Magnolia ‘Galaxy’, unique in form and flower among cultivated magnolias. ‘Galaxy’ is a single-stemmed, tree-form magnolia with ascending branches, the perfect shape for narrow planting sites. In spring, dark red-purple flowers appear after danger of frost, providing a pleasing and long-lasting display. Choose ‘Galaxy’ to shape up your landscape! Winner of a Pennsylvania Horticultural Society Gold Medal Plant Award, 1992. U.S. National Arboretum Plant Introduction Floral and Nursery Plants Research Unit U.S. National Arboretum, U.S. Department of Agriculture, Agricultural Research Service, 3501 New York Ave. NE., Washington, DC 20002 ‘Galaxy’ hybrid magnolia Botanical name: Magnolia ‘Galaxy’ (M. liliiflora ‘Nigra’ × M. sprengeri ‘Diva’) (NA 28352.14, PI 433306) Family: Magnoliaceae Hardiness: USDA Zones 5–9 Development: ‘Galaxy’ is an F1 hybrid selection resulting from a 1963 cross between Magnolia liliiflora ‘Nigra’ and M. sprengeri ‘Diva’. ‘Galaxy’ first flowered at 9 years of age from seed. The cultivar name ‘Galaxy’ is registered with the American Magnolia Society. Released 1980. Significance: Magnolia ‘Galaxy’ is unique in form and flower among cultivated magnolias. It is a single stemmed, pyramidal, tree-form magnolia with excellent, ascending branching habit. ‘Galaxy’ flowers 2 weeks after its early parent M. ‘Diva’, late enough to avoid most late spring frost damage. Adaptable to a wide range of soil conditions. Description: Height and Width: 30-40 feet tall and 22-25 feet wide. It reaches 24 feet in height with a 7-inch trunk diameter at 14 years. Moderate growth rate. Habit: Single-trunked, upright tree with narrow crown and ascending branches. -

December 2015 / January 2016

University of Arizona Yavapai County Cooperative Extension Yavapai Gardens Master Gardener Newsletter December 2015 - January 2016 Mushrooms for Your Kitchen and Garden By Lori Dekker The world of mushrooms Events & Activities is entering a new era. In the past gardeners and MG Association Meeting, NO MEETING IN DECEM- foodies have considered BER, next meeting Jan. 20 in Prescott. 6:30pm the mushroom to be a Alta Vista Gardening Club, Prescott, fourth Tues- garden novelty or a tasty day of the month, 12:30pm. Call 928-458-9508 for culinary delight, while a information. few of us have an interest in the possible health benefits or the psy- cho/spiritual/recreational uses of a few of the more famous mush- Prescott Area Gourd Society, third Wednesday of the rooms. For now, I’d like to consider the potential health benefits of month, 10:30am, at Miller Valley Indoor Art Market, fungi in your soil and therefore your garden. 531 Madison Ave, Prescott When left to their own devices mushrooms, or more accu- rately fungi, are decomposers and eventually constructors. In a nut- Prescott Orchid Society, 4rd Sunday of the month, 1pm at the Prescott Library, (928) 717-0623 shell, they build soil from the raw material of litter and waste found in the garden. Since they digest food outside their bodies, they are Prescott Area Iris Society call 928-445-8132 for date essentially “sweating” digestive enzymes and producing waste as and place information. they grow through their environment. To put it more simply and hap- pily for gardeners, the fungus breaks down complex compounds Mountain View Garden Club, Prescott Valley, Dewey into more simple ones that then become available, leaving behind area, 2nd Friday of month, 1:30pm, call 775-4993 for metabolites that can, in turn, be utilized by other microbes. -

Magnolia X Soulangiana Saucer Magnolia1 Edward F

Fact Sheet ST-386 October 1994 Magnolia x soulangiana Saucer Magnolia1 Edward F. Gilman and Dennis G. Watson2 INTRODUCTION Saucer Magnolia is a multi-stemmed, spreading tree, 25 feet tall with a 20 to 30-foot spread and bright, attractive gray bark (Fig. 1). Growth rate is moderately fast but slows down considerably as the tree reaches about 20-years of age. Young trees are distinctly upright, becoming more oval, then round by 10 years of age. Large, fuzzy, green flower buds are carried through the winter at the tips of brittle branches. The blooms open in late winter to early spring before the leaves, producing large, white flowers shaded in pink, creating a spectacular flower display. However, a late frost can often ruin the flowers in all areas where it is grown. This can be incredibly disappointing since you wait 51 weeks for the flowers to appear. In warmer climates, the late- flowering selections avoid frost damage but some are less showy than the early-flowered forms which blossom when little else is in flower. GENERAL INFORMATION Scientific name: Magnolia x soulangiana Figure 1. Middle-aged Saucer Magnolia. Pronunciation: mag-NO-lee-uh x soo-lan-jee-AY-nuh Common name(s): Saucer Magnolia DESCRIPTION Family: Magnoliaceae USDA hardiness zones: 5 through 9A (Fig. 2) Height: 20 to 25 feet Origin: not native to North America Spread: 20 to 30 feet Uses: container or above-ground planter; espalier; Crown uniformity: irregular outline or silhouette near a deck or patio; shade tree; specimen; no proven Crown shape: round; upright urban tolerance Crown density: open Availability: generally available in many areas within Growth rate: medium its hardiness range 1. -

Pocket Guide for Western North Carolina Partnership (SACWMP), 2011

DO NOT BUY Invasive Exotic Plant List Produced by the Southern Appalachian Cooperative Weed Management pocket guide for western north carolina Partnership (SACWMP), 2011 Western North Carolina has to offer! offer! to has Carolina North Western ) allegheniensis Rubus do not buy these invasives buy natives or alternatives ( Blackberry Allegheny ) alba Quercus ( Oak White of beautiful native plants that that plants native beautiful of ! Mimosa (Silk Tree) Albizia julibrissin Common Serviceberry (Amelanchier arborea) ) nigra Juglans ( Walnut Black Eastern Eastern Redbud (Cercis canadensis) multitude the enjoy and environment, To use your pocket guide: ) virginiana Diospyros ( Persimmon Flowering Dogwood (Cornus florida) whole the of quality the to Add counts. ) pumila Castanea ( Chinquapin the environment a favor on both both on favor a environment the 1 Print on letter-size paper. Japanese Barberry Berberis thunbergii Mountain Pepperbush (Clethra acuminata) wildlife for great Virginia Sweetspire (Itea virginica) doing are you plants, native planting Spicebush (Lindera benzoin) By habitat. species’ of loss the and 2 Cut along outer black line. are the spread of invasive exotic plants plants exotic invasive of spread the are ) fistulosum Eupatorium Butterfly Bush Buddleia davidii Swamp Milkweed (Asclepias incarnata) ( Weed Pye Joe ) ) purpurea (Echinacea Coneflower Purple Purple Coneflower (Echinacea purpurea) Carolina North Western in problems 3 Fold on dotted blue lines. ) syriaca Asclepias ( Milkweed Common Joe Pye Weed (Eupatorium fistulosum) -

![2018 Recommended Street Tree Species List San Francisco Urban Forestry Council Approved [Date]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/4478/2018-recommended-street-tree-species-list-san-francisco-urban-forestry-council-approved-date-1484478.webp)

2018 Recommended Street Tree Species List San Francisco Urban Forestry Council Approved [Date]

2018 Recommended Street Tree Species List San Francisco Urban Forestry Council Approved [date] The Urban Forestry Council annually reviews and updates this list of trees in collaboration with public and non-profit urban forestry stakeholders, including San Francisco Public Works – Bureau of Urban Forestry and Friends of the Urban Forest. While this list recommends species that are known to do well in many locations in San Francisco, no tree is perfect for every potential tree planting location. This list should be used as a guideline for choosing which street tree to plant but should not be used without the help of an arborist or other tree professional. All street trees must be approved by Public Works before planting. The application form to plant a street tree can be found on their website: http://sfpublicworks.org/plant-street-tree Photo by Scott Szarapka on Unsplash 1 Section 1: Tree species, varieties, and cultivars that do well in most locations in San Francisco. Size Evergreen/ Species Notes Deciduous Small Evergreen Laurus nobilis ‘Saratoga’ Saratoga bay laurel Uneven performer, prefers heat, needs some Less than wind protection, susceptible to pests 20’ tall at Magnolia grandiflora ‘Little Gem’ Little Gem magnolia maturity Deciduous Crataegus phaenopyrum Washington hawthorn Subject to pests, has thorns, may be susceptible to fireblight. Medium Evergreen Agonis flexuosa (green) peppermint willow Standard green-leaf species only. ‘After Dark’ 20-35’ tall variety NOT recommended. Fast grower – at more than 12” annually, requires extensive maturity maintenance when young. Callistemon viminalis weeping bottlebrush Has sticky flowers Magnolia grandiflora ‘St. Mary,’ southern magnolia Melaleuca quinquenervia broad-leaf paperbark Grows fast, dense, irregular form, prefers wind protection Olea europaea (any fruitless variety) fruitless olive Needs a very large basin, prefers wind protection Podocarpus gracilior/Afrocarpus falcatus fern pine Slow rooter.