Scotland's Population 2004

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

British Isles

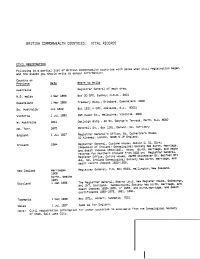

BRITISH COMMONWEALTH COUNTRIES: VITAL RECORDS CIVIL REGISTRATICN Following is a partial list of British Ccmmcnwealth countries with dates when civil registration began, and the places you should writ~ to obtain information: Ccuntry or Prevince Q!!! Where to Write .Au$t'ralia Registrar Ganer-a! of each area. N.S. wales 1 Mar 1856 Sex 30 GPO, Sydney, N.S.W., 2001 Queensland 1 Mar 1856 Treasury Bldg., Brisbane, Queensland 4000 So. Australia Jul 1842 8ex 1531 H Gr\), Adelaide, S.A. 5CCCl Victoria 1 Jul 1853 295 Cuesn St., Melbourne, Victoria XCO W. .Australia 1841 Cak!eigh 61dg., 22 St. Gear-ge's Terrace, Perth, W.A. eoco Nc. Terr. 1870 Mitchell St., Box 1281. OarNin, Nc. Territory England 1 Jul 1837 Registrar General's Office, St. catherine's House, 10 Kinsway. Loncen, 'AC2S 6 JP England. Ireland 1864 Registrar General, Custcme House. Dublin C. 10, Eire, (Recuolic(Republic of Ireland) Genealogical Society has bir~h, marriage, and death indexes 1864-1921. Nete: Birth, rtarl"'iage,rmt'l"'iage, atld death records farfor Nor~hern Ireland frcm 1922 an: Registrar General, Regis~erOffice, Oxford House. 49~5 Chichester St. Selfast STI 4HL, No~ !re1.a.rld Genealcgical Scciety has birth, narriage, and death recordreccrd indexes 1922-l959~ New Z!!aland marriages Registrar General, P.O~ Sox =023, wellingtcn, New Zealand. 1008 birth, deaths 1924 Scotland 1 Jan 1855 The Registrar General, Search Unit, New Register House, Edinburgh, EHl 3YT, SCCtland~ Genealogical Saei~tyScei~ty has bir~h,birth, marriage, and death indexes 1855-1955, or 1956, and birt%'\ crarriage, and death cer~ificates 1855-1875, 1881. -

General Register House National Records of Scotland General Register House

GENERAL REGISTER HOUSE NATIONAL RECORDS OF SCOTLAND GENERAL REGISTER HOUSE ‘A PROPER REPOSITORY’ General Register House was begun in 1774 to the designs of Robert Adam (1728-1792), a Scot who was one of Britain’s greatest architects. It is not only one of his finest public buildings, but also the first purpose-built public record repository in the British Isles. In fact it may be the oldest archive building in the world that is still being used for its original function. A proper home for Scotland’s public records was first proposed in 1722, after the Treaty of Union of 1707 guaranteed that the national records would remain in Scotland. However, for much of the eighteenth century Scotland’s national archives were housed in unsuitable accommodation in Parliament House and other nearby buildings. Eventually, in 1765 a government grant of £12,000 was made available from the forfeited Jacobite estates for the building of ‘a proper repository’. The Register House Trustees only reached agreement on a site when the City gifted the necessary land at the north end of the new North Bridge in 1769. NATIONAL RECORDS OF SCOTLAND ADAM’S DESIGN Largely through the influence of Lord Frederick Campbell, the Lord Clerk Register, Robert Adam and his younger brother James, were appointed architects of Register House in 1772. The Adam brothers believed that you could judge a society by the quality and grandeur of its public buildings, and this commission provided an opportunity to put their beliefs into practice. While the building’s design went through several stages, the main elements of the principal façade and the centralised plan, consisting of a domed rotunda within a quadrangle, were present from the beginning. -

The Statutory Registers of Births, Deaths and Marriages

The Statutory Registers of Births, Deaths and Marriages from Jock Tamson’s bairns: a history of the records of the General Register Office for Scotland by Cecil Sinclair (Edinburgh, 2000) This publication is now out-of-print. Its aim was to describe the three main series of records held by the Registrar General for Scotland in New Register House in Edinburgh and to set them in their historical context. We are making the text from the chapters on the Old Parish Registers, statutory registers and census records available in portable document format (pdf) on this website. Each can be found in the further reading section of the relevant research guide. It is hoped that the content will be of interest to experienced genealogists and to a wide cross-section of the general public who value their personal and social heritage and wish to learn more about it. National Records of Scotland The Statutory Registers of Births, Deaths and Marriages Contents We have made minor amendments to the original text to take account of the merger of the General Register Office for Scotland with the National Archives of Scotland to form the National Records of Scotland on 1 April 2011. We have also divided the chapter into the following sections: 1. The Introduction of Compulsory Civil Registration ............................................... 3 1.1 The 1847 Registration Bill ............................................................................. 4 1.2 The 1854 Registration Act ............................................................................ -

Family History Research at the NATIONAL LIBRARY of IRELAND Getting Started

Family History Research at the NATIONAL LIBRARY OF IRELAND Getting started Beginning the search Your research begins with you and your immediate family. Ask questions of family members you think might know something of your family history. Consult old photographs on which names and dates may be noted, newspaper clippings, old letters, family bibles and family gravestones. Try to establish approximate dates (of births, marriages and deaths) as well as names (forenames and related family names) and places of residence. This information will point the way to relevant records. Religious denomination is also important in determining which records are relevant to your research. 2 CENSUS RECORDS Although a census of the Irish population was taken every ten years from 1821 to 1911, the earliest complete surviving census is for 1901. The 1901 and 1911 Censuses are both fully searchable online, free of charge at www.census.nationalarchives.ie . What information does the census contain? The basic topographical divisions for the census are: County; District Electoral Division; Townland or Street. The household return was filled in and signed by the head of the household on Census night (31 March 1901 and 2 April 1911). There is one record for every household in the country. The information sought was: •Name •Age •Sex •Relationship to the head of the household •Religion •Occupation •Marital status •County or country of birth •Ability to read and write •Knowledge of the Irish language •If “Deaf and Dumb; Dumb only; Blind; Imbecile or Idiot; or Lunatic” In 1911 a significant additional question was asked: married women were required to state the number of years they had been married, the number of their children born alive and the number still living. -

Computerisation of the Indexes to the Statutory Registers of Births, Deaths and Marriages in Scotland

I Technical Papers Number 42 II s October 1990 COMPUTERISATION OF THE INDEXES TO THE STATUTORY REGISTERS OF BIRTHS, DEATHS AND MARRIAGES IN SCOTLAND t International Institute for Vital Registration and Statistics 9650 Rockville Pike Bethesda, Maryland 20814 U.S.A. TABLE OF COIVI3XW.S FOREWORD................................ i BACKGROUND............................... 1 OFTIONS FQR FU3PIXEMENT OF THE PAPER-BASED SYSTEM ........... 2 MANAGINGTHEPRasEcT.......... ................ 3 S W Y ................................ $, FlJTUREPLANs............ .................. '8 ******* This report presents a description of a project to canputerize the indexes of births, deaths, and marriages in Scotland. As in many other countries, for sane time mputers have been used in the production and analysis of vital statistics. Like a number of other countries also, Scotland has more recently given major attention to the application of canputer technology to the operational activ- ities of civil registration. The author of this report provides an account of the planning and implementation of the Caputerisation of Indexes project in the hope that it will give civil registration officials in other countries an idea of the nature and scale of the undertaking, and of some of the problems which are likely to arise. The views expressed in this report are those of the author and do not neces- sarily reflect those of the IIVRS. There are no restrictions on the use of materials published by IIVRS. Materials fmthis publication may be quoted or duplicated without pennission. -

SCOTLAND's POPULATION 2009 the Registrar General's Annual

SCOTLAND’S POPULATION 2009 The Registrar General’s Annual Review of Demographic Trends 155th Edition A National Statistics publication for Scotland. National Statistics are produced to high professional standards set out in the Code of Practice for Official Statistics. They undergo regular quality assurance reviews to ensure that they meet customer needs. They are produced free from any political interference. (Laid before the Scottish Parliament pursuant to Section 1(4) of the Registration of Births, Deaths and Marriages (Scotland) Act 1965) SG/2010/95 Published 6 August 2010 General Register Office for Scotland, © Crown copyright 2010 2 General Register Office for Scotland, © Crown copyright 2010 ANNUAL REPORT OF THE REGISTRAR GENERAL of BIRTHS, DEATHS AND MARRIAGES for SCOTLAND 2009 155th Edition To Scottish Ministers I am pleased to let you have my Annual Report for the year 2009, which will be laid before the Scottish Parliament pursuant to Section 1(4) of the Registration of Births, Deaths and Marriages (Scotland) Act 1965. Duncan Macniven Registrar General for Scotland 6 August 2010 3 General Register Office for Scotland, © Crown copyright 2010 4 General Register Office for Scotland, © Crown copyright 2010 CONTENTS Page Introduction 7 Important Points 9 Chapter 1 Population 15 Chapter 2 Births 25 Chapter 3 Deaths 32 Chapter 4 Life Expectancy 45 Chapter 5 Migration 53 Chapter 6 Marriages and Civil Partnerships 62 Chapter 7 Divorces and Dissolutions 66 Chapter 8 Adoptions and Gender Recognition 68 Chapter 9 Households and Housing 69 Chapter 10 Very Near the Truth: a history of the census in 77 Scotland Appendix 1 Summary Tables 108 Appendix 2 Notes & Definitions 111 Notes on Statistical Publications 117 5 General Register Office for Scotland, © Crown copyright 2010 6 General Register Office for Scotland, © Crown copyright 2010 Introduction Scotland’s economy was in recession from the summer of 2008 to the autumn of 2009. -

Scotland's People in Time and Space

Scotland’s People in Time and Space Geography and the work of the General Register Office for Scotland Duncan Macniven Registrar General for Scotland General Register Office for 1 S C O T L A N D information about Scotland's people The work of GROS • Registering births, deaths, marriages etc • Taking the decennial census • Using these and other sources to publish demographic statistics • Using these and other sources for family history General Register Office for 2 S C O T L A N D information about Scotland's people An Act to provide for the better Registration of Births, Deaths and Marriages in Scotland, 1854 General Register Office for 3 S C O T L A N D information about Scotland's people First Annual Report General Register Office for 4 S C O T L A N D information about Scotland's people First Annual Report General Register Office for 5 S C O T L A N D information about Scotland's people First Annual Report General Register Office for 6 S C O T L A N D information about Scotland's people Registration Districts in 1855 General Register Office for 7 S C O T L A N D information about Scotland's people 1861 Census General Register Office for 8 S C O T L A N D information about Scotland's people 1861 Census General Register Office for 9 S C O T L A N D information about Scotland's people Geography’s role today • Family history • Demography General Register Office for 10 S C O T L A N D information about Scotland's people ScotlandsPeople General Register Office for 11 S C O T L A N D information about Scotland's people To genealogists, place -

Guidebook for the Clergy

General Register Office Guidebook for The Clergy General Register Office Issued: 2011 Last updated: February 2015 Contents Page Introduction 4 Marriage 1 General • Roles and responsibilities 5 • Hours and place of marriage 5 • Restrictions on marriage 6 • Access 6 • Witnesses 6 • Registration stock 6 • Missing or stolen safe or registration stock 7 • Damaged register books 7 • Ink 7 2 Preliminaries • Preliminaries to Marriage 8 • Ecclesiastical Preliminaries 8 • Superintendent Registrar's Certificate in lieu of Ecclesiastical 8 Preliminaries • Nationality requirements 9 • European Economic (EEA) Nationals 9 • Non European Economic (EEA) Nationals 9 • Evidence of British, EEA or Swiss Nationality 9 • Evidence of current use of name 10 • Giving notice of intent to marry 11 • Qualifying connection 11 • Notice Period 12 • One party resident in Scotland 13 • One party resident in Ireland 13 • Publication of banns - service personnel 13 • Publication of banns on board HM ships 13 • Two marriage ceremonies on the same day 13 • Religious ceremony after a civil marriage 14 • Re-marriage 14 3 Ceremony • Pre-marriage checks 15 • Marriage by Superintendent Registrar’s Certificate 15 • Pre-marriage questions 15 • Forced marriages 16 • Sham marriage 16 • Mental capacity 17 4 Registrations • Marriage registers 18 • Commencement of entries 18 • Completing the register entries 19 • Description of authority on which marriage was solemnized 22 1 • Examination of entry by the parties to the marriage 22 • Signing the entry 22 • Bilingual registration in Wales -

Guide to Marriage Certificates

Guide to Marriage certificates Collect the evidence for one of the most important days in your ancestors’ lives and take your research back another generation. Reveal your family unions How to find an index reference Marriage certificates are key documents The GRO provides a public index that lists and provide a wealth of information on basic details of every marriage recorded in two strands of your family tree. They will England and Wales since 1837. The index is help take you back to the next generation divided into four quarters for each year and by providing the father’s name can be viewed in microfiche format at certain for the bride and groom as well as their libraries (see our leaflet ‘Discover your occupations and may lead to surprising Family History’). discoveries, for instance, the witnesses may be unknown family members. Marriage indexes are also available to search on FreeBMD. This free-to-use The General Register Office (GRO) in website has an almost complete Southport holds comprehensive records transcription of the indexes for England and of all marriages recorded in England and Wales from 1837 to 1983. You can also Wales from 1837 onwards as well as search the indexes for a fee using records for some British Nationals married commercial websites. overseas. Once you have found the right marriage record you will need to note the following: • full name of the person on the certificate • year and quarter in which the marriage was registered • registration district • volume and page number of the entry For information on our current prices please refer to the booklet on GOV.UK 'How to order and Pay for Civil Registration Records' or visit www.gov.uk/ bmdcertificates click 'start now' and select 'Most Customers Want to Know' Guide to marriage certificates When married 1 This marriage happened on 18 September 1907 so it will be found in the GRO indexes for the September quarter for 1907. -

UK Exist in the Way How Vital Events Are Reported There

HUMAN FERTILITY DATABASE DOCUMENTATION: THE UNITED KINGDOM, ENGLAND & WALES, SCOTLAND, AND NORTHERN IRELAND Authors: Julie Jefferies formerly Office for National Statistics Kryštof Zeman Vienna Institute of Demography, Austrian Academy of Sciences E-mail: [email protected] Last revision: 28 August 2020 1 General information This report documents data provided for the Human Fertility Database project for the United Kingdom. In the United Kingdom, the vital statistics data are collected by three separate statistical agencies for England & Wales, for Scotland, and for Northern Ireland. There are significant differences between these agencies in the reporting and publishing of birth statistics. The territorial and administrative division of the United Kingdom is reflected in the HFD through the separate publication of data for England & Wales (country code GBRTENW1), Scotland (country code GBR_SCO), and Northern Ireland (country code GBR_NIR). Data for the entire United Kingdom (country code GBR_NP) are obtained by summing up data for the three countries. The procedure is as follows: births by Lexis triangles (age and birth cohort of mother) and exposure population by Lexis triangles (age and year of birth) are first calculated for each country and then these data are combined to produce corresponding Lexis data for the entire United Kingdom. Please refer to the HFD Methods Protocol for details. The data consist of age-specific numbers of births and total numbers of births by calendar month and year. The Human Fertility Database (HFD) for the United Kingdom is based on the official data on birth counts published in vital statistics publications and in individual birth records, which were kindly provided by the Office for National Statistics of England and Wales (ONS), the General Register Office for Scotland (GRO), and the Northern Ireland Statistics and Research Agency (NISRA). -

Accessing Birth Records Scotland Mar 2016.Pmd

Accessing birth records INFORMATION FOR PEOPLE WHO HAVE BEEN ADOPTED IN SCOTLAND March 2016 CONTENTS The National Archives of Scotland 2 Princes Street Introduction .. .. .. .. 1 Edinburgh How can Social Work help? .. .. 1 EH1 3YY What information am I entitled to? .. .. 2 Tel 0131 535 1314 www.nas.gov.uk What information can the General Register for Scotland provide? .. .. .. 3 What information will I get from my original Birth Certificate? .. .. .. 4 What is an Adoption Certificate?.. .. 5 What information can the Court Process Papers provide? .. .. .. .. 6 What might the Court Process Papers tell you? 7 Adoption Agency Records .. .. 9 Records held by Aberdeenshire Council .. 9 How might you go about your search? Searches at the General Register Office .. 11 If you were born in Scotland but adopted elsewhere in the UK .. .. 13 If you were adopted in Scotland but born elsewhere in the UK .. .. 13 Contacting birth relatives .. .. 13 Services at Family Care Birthlink Adoption Contact Register for Scotland .. .. .. 14 The Scottish Adoption Registry .. 14 Adoption Counselling Centre .. .. 14 Additional Sources of Information .. .. 15 Representation and Complaints .. .. .. 15 Further Reading .. .. .. 15 Useful Addresses .. .. .. 16 Useful Addresses Introduction Much of the information included in this Leaflet is taken from a very This leaflet has been written to provide information for useful guide, published by Birthlink Adoption Counselling Centre, people who have been adopted in Scotland and who wish called Relatively Clear - Search Guide for Adopted People in to seek information about their birth records. Scotland £8.99. Wanting to find out more about our origins is an important Birthlink part of establishing our identity. -

Family Policy: Partners, Divorce and Dissolution

Family Policy: Partners, divorce and dissolution Version 1.0 Page 1 of 44 Published for Home Office staff on 29 May 2019 Contents Partners, divorce and dissolution ............................................................................... 1 Contents ..................................................................................................................... 2 About this guidance .................................................................................................... 4 Changes from last version of this guidance ............................................................ 4 Contacts ................................................................................................................. 4 Publication .............................................................................................................. 4 Recognition of marriage and civil partnership ............................................................ 5 Marriage and civil partnership in the UK ................................................................. 5 Overview ............................................................................................................. 5 England and Wales ............................................................................................. 6 Scotland .............................................................................................................. 7 Northern Ireland .................................................................................................. 7 Age to enter