Haytor Audio Walk Transcript

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Dartmoor | Devon

DARTMOOR | DEVON DARTMOOR | DEVON Haytor 2 miles | Bovey Tracey 3 miles | Newton Abbot 8 miles | Exeter 17 miles (All distances are approximate) ‘Nestled on Dartmoor National Park, a charming family home in a truly remarkable private setting with breath-taking views at the heart of a 247 acre farm with pasture, woods and moorland.’ Grade II Listed House with Entrance Hall | Dining Room | Scandinavian Hall | Sitting Room | Study Office | Kitchen/Breakfast Room Main Bedroom Suite with Dressing Room and Ensuite Bathroom | 6 further Bedrooms and Bathrooms Second Floor Sitting Room and Kitchen Beautiful terraced Gardens | Former Tennis Court | Summer House Extensive Range of Traditional Buildings | Farm Buildings 4 Bedroom Farmhouse Pasture | Mature Mixed Woodland | Moorland Lodge Cottage In all about 247.86 acres Available as whole or in 2 lots Viewing by appointment only. These particulars are intended only as a guide and must not be relied upon as statements of fact. Your attention is drawn to the Important Notice on the last page of the brochure. LOCAL AREA The Yarner Estate is situated on the eastern of Haytor are just to the west of the estate wide range of conveniences along with a good, quick access to Exeter and the M5. edge of Dartmoor National Park next to the with spectacular views across Dartmoor and church, restaurants, cafés, and pubs. Bovey Exeter St Davids provides regular Intercity East Dartmoor National Nature Reserve in a the South Devon coast. Castle has a superb 18-hole golf course and rail services to the Midlands and London remarkable peaceful elevated location. Adjacent Yarner Woods is part of a extensive leisure facilities and lies about Paddington and Waterloo. -

Offers in the Region of £55,000 for Sale by Private Treaty

NEWTON ABBOT ~ ASHBURTON ~ TOTNES ~ CHAGFORD ~ ANTIQUES SALEROOM, ASHBURTON Draft details subject to vendor’s approval 10/01/2019 2.77 Acres of Equestrian land with planning permission for a stable block and yard at Lower Bowdley, Druid, Ashburton, Devon, TQ13 7HR Offers in the Region of £55,000 For Sale by Private Treaty Contact Newton Abbot Rural Department: Rendells, 13 Market Street, Newton Abbot, Devon TQ12 2RL Tel. 01626 353881 Email: [email protected] Equestrian Land and Planning Permission for Stables at Lower Bowdley, Ashburton, Devon, TQ13 7HR 10/01/2019 Situation: Situated of a the B3387 lane to Haytor 2 miles north west of the town of Ashburton within Dartmoor National Park surrounded by similar fields, woodland and other equestrian properties. Description: A gently sloping free draining field of permanent grassland with excellent views out towards rolling countryside and Hennock with the benefit of a hard core entrance and track, good stock fencing and Devon banks containing mixed native hedgerow species. A great opportunity to build a new equestrian holding with stable block suitable for two horses and hard standing yard area. Tenure: The property is freehold and offered for sale with vacant possession. Plan: The plan attached has been prepared from Promap ordnance survey plans but must be treated as a guide. Planning Consent for Stable Block Was granted by Dartmoor National Park under application number 0411/17 permission being granted on the 9th of October 2017. A copy of the permission and the plan is included in the details. The site is at the West corner of SX (7471). -

Easy-Going Dartmoor Guide (PDF)

Easy- Contents Introduction . 2 Key . 3 Going Dartmoor National Park Map . 4 Toilets . 6 Dartmoor Types of Walks . 8 Dartmoor Towns & Villages . 9 Access for All: A guide for less mobile Viewpoints . 26 and disabled visitors to the Dartmoor area Suggested Driving Route Guides . 28 Route One (from direction of Plymouth) . 29 Route Two (from direction of Bovey Tracey) . 32 Route Three (from direction of Torbay / Ashburton) . 34 Route Four (from direction of the A30) . 36 Further Information and Other Guides . 38 People with People Parents with People who Guided Walks and Events . 39 a mobility who use a pushchairs are visually problem wheelchair and young impaired Information Centres . 40 children Horse Riding . 42 Conservation Groups . 42 1 Introduction Dartmoor was designated a National Park in 1951 for its outstanding natural beauty and its opportunities for informal recreation. This information has been produced by the Dartmoor National Park Authority in conjunction with Dartmoor For All, and is designed to help and encourage those who are disabled, less mobile or have young children, to relax, unwind and enjoy the peace and quiet of the beautiful countryside in the Dartmoor area. This information will help you to make the right choices for your day out. Nearly half of Dartmoor is registered common land. Under the Dartmoor Commons Act 1985, a right of access was created for persons on foot or horseback. This right extends to those using wheelchairs, powered wheelchairs and mobility scooters, although one should be aware that the natural terrain and gradients may curb access in practice. Common land and other areas of 'access land' are marked on the Ordnance Survey (OS) map, Outdoor Leisure 28. -

Information Ashburton, Haytor (DNPA, Off Route), Bovey Tracey CROSS TRACEY Please Refer Also to the Stage 3 Map

O MO R T W R A A Y D w w k u w . o .d c ar y. tmoorwa Start SX 7561 6989 The Bullring, centre of Ashburton Elevation Profile Finish SX 8145 7823 Entrance to Mill Marsh Park, 400m Bovey Bridge, Station Road, Bovey Tracey 200m Distance 12.25 miles / 19.75km Total ascent 2,303ft / 702m 0.0km 2.0km 4.0km 6.0km 8.0km 10.0km 12.0km 14.0km 16.0km 18.0km 20km Refreshments Ashburton, Haytor (off route), Parke, Bovey Tracey 0.0mi 1.25mi 2.5mi 3.75mi 5mi 6.25mi 7.5mi 8.75mi 10.63mi 11.25mi 12.5mi Public toilets Ashburton, Haytor (off route), Parke, Bovey Tracey ASHBURTON HALSANGER HAYTOR ROCKS PARKE BOVEY Tourist information Ashburton, Haytor (DNPA, off route), Bovey Tracey CROSS TRACEY Please refer also to the Stage 3 map. At the end of the wood follow the S From the centre of Ashburton, at the junction of West, East and track right, uphill. Ascend steadily, North streets (The Bullring), head up North Street, soon passing the then descend (muddy in winter) to Town Hall. The road meets and follows the River Ashburn. reach farm buildings at Lower Whiddon Farm. Turn right, then head 1 About 75yd later, just before the road curves left, turn right and up the farm drive past Higher ascend steps. Pass through a kissing gate into fields, to reach a Whiddon to reach a lane T-junction footpath junction. Take the left (lower) footpath, signed to Cuddyford (a handy seat offers the chance of a Cross, along the left edge of two fields, crossing a stile onto a lane. -

Signed Walking Routes Trecott Inwardleigh Northlew

WALKING Hatherleigh A B C D E F G H J Exbourne Jacobstowe Sampford North Tawton A386 Courtenay A3072 1 A3072 1 Signed Walking Routes Trecott Inwardleigh Northlew THE Two MOORS WAY Coast Plymouth as well as some smaller settlements Ashbury Folly Gate to Coast – 117 MILES (187KM) and covers landscapes of moorland, river valleys and pastoral scenery with good long- The Devon Coast to Coast walk runs between range views. Spreyton Wembury on the South Devon coast and The route coincides with the Two Castles 2 OKEHAMPTON A30 B3219 2 Trail at the northern end and links with the Lynmouth on the North Devon coast, passing A3079 Sticklepath Tedburn St Mary through Dartmoor and Exmoor National Parks South West Coast Path and Erme-Plym Trail at South Tawton A30 Plymouth; also with the Tamar Valley Discovery Thorndon with some good or bad weather alternatives. B3260 Trail at Plymouth, via the Plymouth Cross-City Cross Belstone The terrain is varied with stretches of open Nine Maidens South Zeal Cheriton Bishop Stone Circle Whiddon Link walk. Bratton A30 Belstone Meldon Tor Down Crokernwell moor, deep wooded river valleys, green lanes Clovelly Stone s Row and minor roads. It is waymarked except where Cosdon Spinsters’ Drewsteignton DRAKE'S TRAIL Meldon Hill Rock it crosses open moorland. Reservoir Throwleigh River Taw River Teign Sourton West Okement River B3212 3 Broadwoodwidger Bridestowe CASTLE 3 The Yelverton to Plymouth section of the Yes Tor East Okement River DROGO Dunsford THE TEMPLER WAY White Moor Drake’s Trail is now a great family route Sourton TorsStone Oke Tor Gidleigh Row Stone Circle Hill fort – 18 MILES (29KM) High Hut Circles thanks to improvements near Clearbrook. -

DARTMOOR BIRD REPORT 2018 Peter Reay & Fiona Freshney

DARTMOOR BIRD REPORT 2018 Peter Reay & Fiona Freshney [email protected] Scorhill Mire (Gullaven Brook), the best Snipe site during the 2018/19 survey (Fiona Freshney) CONTENTS INTRODUCTION SOME NOTABLE RECORDS WEATHER REFERENCES LOOKING BACK TO THE 2008 REPORT SPECIES ACCOUNTS A SUMMARY OF CURRENT DARTMOOR BIRD RESEARCH 1 INTRODUCTION This report, like those for 2015 and 2017, replaces the Dartmoor Bird Report, published from 1996 to 2014 by the Dartmoor Study Group. It relates to the same geographical area covered both by its predecessors and The Birds of Dartmoor (Smaldon 2005). This comprises the area within the Dartmoor National Park Authority (DNPA) boundary, with the addition of the china clay districts around Lee Moor, Shaugh Moor and Crownhill Down, left out of the National Park designation for political and business reasons. The bulk of the report comprises species accounts, but it also includes brief reviews of the weather in 2018, the Dartmoor Bird Report of 2008 and current Dartmoor bird projects and surveys. A more detailed description of the latter will appear in a Review of Dartmoor Bird Research 2018-19 to be published in Devon Birds in 2020 (Freshney & Reay, in prep.). The species accounts aim to provide a summary of birds recorded on Dartmoor in 2018. It is hoped that the production of the report will encourage more active submission of records and so help create a more complete picture of Dartmoor’s birds in 2019 and beyond. The records used are mostly those submitted to Devon Birds for 2018 (including those from the national BTO surveys) and assigned to the Dartmoor parent site. -

26 July 2019 Reports

NPA/DM/19/018 DARTMOOR NATIONAL PARK AUTHORITY DEVELOPMENT MANAGEMENT COMMITTEE 26 July 2019 APPLICATIONS FOR DETERMINATION BY THE COMMITTEE Report of the Head of Development Management INDEX Item No. Description 1. 0346/18 - Erection of 40 dwellings, including 14 affordable dwellings and associated infrastructure (Full Planning Permission), land adjacent to Fairfield, South Brent 2. 0209/19 - Erection of general purpose agricultural building (12m x 4m) (Full Planning Permission), Violet House, Haytor 3. 0250/19 - Erection of single storey side extension to house (Full Planning Permission - Householder), Hillman Cottage, Horrabridge 9 10 1. Application No: 0346/18 District/Borough:South Hams District Application Type: Full Planning Permission Parish: South Brent Grid Ref: SX703598 Officer: Helen Maynard Proposal: Erection of 40 dwellings, including 14 affordable dwellings and associated infrastructure Location: land adjacent to Fairfield, South Brent Applicant: Eden Land Planning and Midas Commercial Developments Recommendation That, subject to the completion of a Section 106 Agreement in respect of affordable housing provision and a contribution of £23,343 towards the shortfall in open space, sport and recreation facilities, permission be GRANTED. Condition(s) 1. The development hereby permitted shall be begun before the expiration of three years from the date of this permission. 2. The development hereby approved shall, in all respects, accord strictly with drawings numbered 1764/058, 17648/1062B, 17648/054B, 1312/301B, 1312/331C, 1312/309B, -

NCA Profile:150 Dartmoor

National Character 150. Dartmoor Area profile: Supporting documents www.naturalengland.org.uk 1 National Character 150. Dartmoor Area profile: Supporting documents Introduction National Character Areas map As part of Natural England’s responsibilities as set out in the Natural Environment 1 2 3 White Paper , Biodiversity 2020 and the European Landscape Convention , we are North revising profiles for England’s 159 National Character Areas (NCAs). These are areas East that share similar landscape characteristics, and which follow natural lines in the landscape rather than administrative boundaries, making them a good decision- Yorkshire making framework for the natural environment. & The North Humber NCA profiles are guidance documents which can help communities to inform their West decision-making about the places that they live in and care for. The information they contain will support the planning of conservation initiatives at a landscape East scale, inform the delivery of Nature Improvement Areas and encourage broader Midlands partnership working through Local Nature Partnerships. The profiles will also help West Midlands to inform choices about how land is managed and can change. East of England Each profile includes a description of the natural and cultural features that shape our landscapes, how the landscape has changed over time, the current key London drivers for ongoing change, and a broad analysis of each area’s characteristics and ecosystem services. Statements of Environmental Opportunity (SEOs) are South East suggested, which draw on this integrated information. The SEOs offer guidance South West on the critical issues, which could help to achieve sustainable growth and a more secure environmental future. -

Easton Court Easton Cross Chagford Tq13 8Jl

FOR SALE FOR EASTON COURT EASTON CROSS CHAGFORD TQ13 8JL : THE PROPERTY a commercial style kitchen with an collection collated by the Hotel in the There is also a wild garden with fish attached utility room. The original house 1930’s and 40’s and carefully maintained pond beyond. From the road is a large This Grade II Listed 16th century has many fantastic character features by the current owner, along with original parking bay, plus parking for around 8 detached longhouse with fabulous including wonderful fireplaces, exposed guest books with guests from its history cars (15.7m x 8.4m) within the walled views is situated in the Dartmoor beams and beautiful doors. The library, including the Waugh brothers, Richard perimeter. National Park, close to the lovely town of containing books with links to the hotel, Widmark and John Steinbeck. Chagford & Castle Drogo. The house is and main living room are great examples Outside it has an enclosed garden with granite under thatch, with the B&B wing and ceiling heights are good throughout. Outside we find formal gardens in front hot tub and electric sauna, plus parking being under slate. There is also mains gas central heating. of the original house (south-facing for 3-4 cars with a separate access to circa. 15m x 14m) and the more recent the hotel, and an open fronted double The accommodation includes eight THE LIBRARY ‘B&B wing’ with lawns extending garage plus store. en-suite bedrooms in total, with to approximately 40m x 18m with four spacious reception rooms, plus The library contains an original book wonderful far reaching views to enjoy. -

Glencoe Glencoe Ilsington, Newton Abbot, Devon, TQ13 9RS

Glencoe Glencoe Ilsington, Newton Abbot, Devon, TQ13 9RS SITUATION AND DESCRIPTION rear garden with far-reaching views. Nestled on the edge of the village Walk-in dressing area and modern en- Glencoe offers uninterrupted views suite shower room with shower across Dartmoor. The nearby amenities enclosure, wash hand basin, WC, towel include; Primary school, village shop, rail and window. Family bathroom with church, public house and health facilities bath, WC, wash hand basin, large walk- at the nearby Country House Hotel. in shower enclosure. Stairs lead to a Further public house and restaurants can large studio loft with double glazed, A38 3 miles be found close by in the hamlet of Haytor skylight windows. A large storage area Totnes 15 miles Vale. All of which are within walking with standing height and skylight windows, can be accessed through a Exeter 18 miles distance of Glencoe. Further services can be found at Bovey Tracey and hatch. Ashburton. Set within Dartmoor National Park, the property is within easy access OUTSIDE to the open moorland, a popular destination for walking, horse riding and Ample driveway parking to the front of cycling. the property and double garage to one end. The property sits in over an acre A fabulous detached family Glencoe is a fantastic four bedroom consisting of mainly lawned gardens with detached 1930's residence located on further mature broad leaf woodland residence with far reaching the edge of the desirable village of falling to the River Lemon. The gardens views over the countryside Ilsington. The property offers deceptively are a real delight and anyone keen on spacious accommodation along with gardening has much scope to create and Dartmoor beyond. -

Lowton Moretonhampstead, Devon Lowton Moretonhampstead, Devon

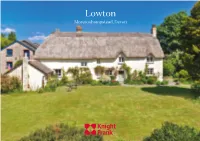

Lowton Moretonhampstead, Devon Lowton Moretonhampstead, Devon Lowton is a historic Grade II*Listed farmhouse with stunning rural views and attractive gardens, ideal for multi-generational living. Chagford 4 miles, Exeter 14 miles (All distances are approximate) Accommodation and amenities Grade II* Listed farmhouse | Grooms Cottage | The Hayloft | Medieval stone barn Garaging | 3 car ports and stores Over 5,700 sqft of accommodation In all about 13.2 acres Exeter 19 Southernhay East, Exeter EX1 1QD Tel: 01392 423111 [email protected] knightfrank.co.uk Situation Lowton is situated in a fabulous rural location with stunning countryside views reaching out as far as Haytor and Easdon Tor, within the Dartmoor National Park. The popular town of Moretonhampstead is just under a mile away whilst The House the delightful Stannary town of Chagford is 4 miles, both towns providing a good range of local facilities. There are wonderful footpaths in the locality to explore Dartmoor and the surrounding countryside. The cathedral and university city of Exeter (14 miles) is easily accessed, near which is the M5 motorway and Exeter International Airport. The House Lowton is early-mid 16th Century with late 16th /early 17th Century and 18th Century alterations. Of rendered granite rubble walls under a thatched roof, hipped to left and gabled to right end. The entrance from the south is a very unique part of the house forming the original cross passage with beautiful plank and muntin screen and delabole slate floor. There is a large cloakroom with an adjoining wc with wash basin. Stairs to the first floor. -

CHAGFORD Gateway to Dartmoor

in 1903. in m ine in the area closed area the in ine valuing. The last tin last The valuing. tin for weighing and weighing for tin m iners brought their brought iners ori eo.Here, Devon. in four a Stannary town, one of one town, Stannary a I n 1305, Chagford became Chagford 1305, n where the gorse grows”. gorse the where originally dedicated in 1261. in dedicated originally Saxon Times. The name means “The ford “The means name The Times. Saxon ae akt h 5hcnuy although century, 15th the to back dates a nd Chagford was probably established in established probably was Chagford nd 1 6th century. St Michael’s Parish Church Parish Michael’s St century. 6th Man has lived here for thousands of years of thousands for here lived has Man W C Stannary Court. Stannary b uildings, many dating from the from dating many uildings, over the world throughout the year. the throughout world the over point in Chagford, is on the site of the old the of site the on is Chagford, in point see old thatched granite thatched old see m agnet that attracts visitors from all from visitors attracts that agnet T he eight-sided Market House, a focal a House, Market eight-sided he ANDER AROUND and you’ll and AROUND ANDER AFR sa nqepae a place: unique an is HAGFORD Tracey Elliot-Reep Tracey © outh m Dart 8 A3 ybridge Iv outh m y Pl Y A ORB T Totnes Torquay eigh l fast ck u B 1 A38 A386 2 1 2 3 B Abbot ewton N Ashburton etown c rin P T ck isto v a oor -M the - in 3357 B - be m o c ide W A380 ey c Tra ostbridge P ey v o B 2 1 2 3 B 2 A38 A 38 Dartmoor 1 3 J stead mp oretonha M M5 Chagford Dunsford 2 A38 2 1 2 3 B Drewsteignton eter Ex A30 w je “The y sa ranite setting”.