RAGE Reportv15.Qxp

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Shiatsu and Cancer

SHIATSU AND CANCER As with many other complementary therapies a major benefit for people affected by cancer is having time to talk, be listened to and heard in a safe environment. The shiatsu practitioner is trained to relate to people as individuals and assess their physical, mental, emotional and spiritual needs – essential in recovery from cancer. The power of touch used in shiatsu should never be underestimated. Shiatsu can offer valuable support from the point of diagnosis, immediately after surgery and throughout radiotherapy and chemotherapy. Once treatment is finished, shiatsu sessions can aid recovery, help to renew energy and motivate people to take responsibility for their wellbeing. Shiatsu offers a drug free solution to reduce side effects such as pain, nausea and lethargy associated with surgery, radiotherapy and chemotherapy and may help to reduce hot flushes in hormone therapy. Shiatsu restores and balances energy levels and triggers the relaxation response easing stress and tension in the body and mind and encouraging restful sleep. Shiatsu facilitates emotional release without the need to ask searching questions, helping to reduce levels of fear and anxiety, dissipate anger and frustration and assist the grieving process. Shiatsu moves the lymph helping to minimise the risk of lymphoedema. Shiatsu assists with the detoxification process. Shiatsu helps to restore hormonal balance in hormone related cancers Shiatsu encourages correct posture, breathing, stretching and exercise Shiatsu may help to boost the immune response Shiatsu improves circulation and enhances wellbeing Shiatsu awakens the spirit and inspires hope for the future. Shiatsu helps people to get back in control, encourages self management and empowers people to take responsibility for their healing and well-being, thereby improving their quality of life. -

Eurohealth Vol 13 No 3 MENTAL HEALTH ECONOMICS

Eurohealth RESEARCH • DEBATE • POLICY • NEWS Volume 13 Number 3, 2007 Making the economic case for mental health in Europe France: Health promotion for migrants Intergovernmental relations in Italian health care Health inequalities in the decentralised Spanish health care system Migration of Flemish doctors to the Netherlands • Romania: Pharmaceutical pricing and reimbursement Austria: Electronic health record development • Institutional and community care for older people in Turkey Eurohealth A timely opportunity for Europe LSE Health, London School of Economics and Political The European Commission has just published its new Science, Houghton Street, London WC2A 2AE, United Kingdom C Health Strategy ‘Together for Health: A Strategic fax: +44 (0)20 7955 6090 Approach for the EU 2008–2013’. Building on current www.lse.ac.uk/LSEHealth work, this Strategy aims to provide, for the first time, Editorial Team an overarching strategic framework spanning core EDITOR: issues in health, as well as in ‘health in all policies’ David McDaid: +44 (0)20 7955 6381 and global health issues. email: [email protected] O FOUNDING EDITOR: Elias Mossialos: +44 (0)20 7955 7564 The explicit inclusion of the promotion of mental, as email: [email protected] well as physical, health is a timely reminder of the DEPUTY EDITORS: importance of looking at health holistically. Poor Sherry Merkur: +44 (0)20 7955 6194 mental health affects more than 130 million Europeans email: [email protected] Philipa Mladovsky: +44 (0)20 7955 7298 M at a cost to every European household of more than email: [email protected] € 2,000 per annum. -

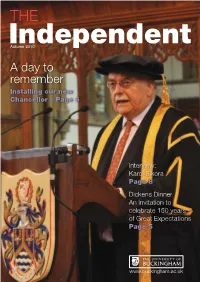

A Day to Remember

THE Independent Autumn 2010 Adayto remember Installing our new Chancellor – Page 6 Interview: Karol Sikora Page 8 Dickens Dinner An invitation to celebrate 150 years of Great Expectations Page 5 www.buckingham.ac.uk Annual Fund Help us remain No 1 in the National Student Survey by donating to the following projects: • Multimedia Centre • Video Equipment • Bursaries & Prizes • Hardship Fund Thank you to everyone whose donations have enabled the Annual Fund to successfully contribute to the following projects: • Campus Radio Station • Memorial Garden • The Cellars, Verney Park • BSc in Business Enterprise Prize • University Minibus • Wellness Centre • SU Music Equipment To Donate Go To https://extranet.buckingham.ac.uk/alumnet/ubf-aaf.aspx ALUMNI Annual Fund 2 Autumn 2010 Contents 3 Welcome Welcome to the Comment 4 From the Vice-Chancellor autumn issue This year, 2010, has been a good University News 5 one for the university because Great Dinner Expected; for the fifth year running Most Satisfied Students; Buckingham hit the top spot for student satisfaction in the Afternoon Tea at the House National Student Survey. It is a of Lords; At Home with your spectacular achievement and VC; New Faces; Leavers our thanks go to students and staff for the support and effort involved in keeping us at Looking to the Future Number One. 7 Installation of the new The university is changing all the time and experienced a surge in student numbers in September, Chancellor doubling its intake compared with last year. Part of the reason, we think, is our position in the league tables - we entered the league table Feature – Escape from the in The Independent newspaper for the first time this year coming in at 8 Day Job 20th position, and we also appear this year in the teaching training league table, in fifth position. -

Side Effects

WARNING: SIDE EFFECTS A check-up on the federal health law United States Senate 112th Congress Senator Tom Coburn, M.D. Senator John Barrasso, M.D. March 2012 0 Contents Introduction………………….……………………………………………………………………………………..2 1. Millions of Americans Could Lose Their Health Insurance Plan……………………………...5 2. Hundreds of Billions of Dollars of Tax Hikes………………………………………………………….9 3. New Insurance Rule Increases Costs, Reduces Choices…………………………………………11 4. Data Confirms Law Is a Government-Takeover of Health Care……………………………...16 5. Findings from New Taxpayer-Funded Research Institute Could Be Used to Deny Payment for Patients’ Care………………………………………………20 6. New Medicare Bureaucracy Empowered………………….………………………………………...27 7. New Insurance Cooperatives to Waste Taxpayers’ Dollars……………………….………….30 8. Device Tax Stifles Innovation…………………………………………………………………………..…34 1 Introduction Two years ago, supporters of the President’s health care law said Congress needed to pass the health bill so the American people could find out what was in it.1 After the President signed the bill into law, supporters guaranteed that “as people learn about the bill….it’s going to become more and more popular.”2 Over the past twenty four months, American families have learned more about the President’s health care law and do not like what they see. Higher insurance premiums. A coming state budget-busting Medicaid expansion. Fewer choices. Less freedom and more government interference. Cuts to Medicare by unelected government bureaucrats. Thousands of pages of regulations. An unconstitutional mandate to buy health insurance. Penalties on employers threatening job creation. Billions of dollars in tax hikes and, once fully implemented, $2.6 trillion in new health care spending. It’s no wonder that a majority of Americans oppose the law today.3 In fact, poll after poll shows that a majority of Americans want the Supreme Court to overturn the law.4 As practicing physicians, we believed – long before Congress passed the health spending law – that the health care law did not represent real health care reform. -

Professor Karol Sikora

THE MAGAZINE FOR DULWICH COLLEGE ALUMNI FEATURING PROFESSOR KAROL SIKORA With reflections on the pandemic and its impact on cancer PLUS KYLE KARIM AT LEGO AND THE ORIGINS OF SOCCER AT DC WELCOME TO THE MAGAZINE FOR DULWICH COLLEGE ALUMNI PAGE 03 Meet the Team Trevor Llewelyn Matt Jarrett (72-79) Hon Secretary of Director of Development the Alleyn Club As I write this editorial the College is currently In the last edition of OA I hoped that our new format closed to all but the children of key workers. It is would allow us to look in greater depth at the only the third time in the school’s long history that lives and careers of OAs. That we have been able this has happened and two of those have been in to do with interviews with sailor Mark Richmond, response to Covid 19. The only other time our gates opera singer Rodney Clarke and Kyle Karim who Joanne Whaley have been shut was during the Second World War as Director of Marketing for Lego may, by his own Kathi Palitz when we temporarily moved out of the capital in admission, just have the best job in the world. Alumni & Parent Database and Operations order to share the facilities of Tonbridge School. It Relations Manager was not a success and the boys soon returned to Like much of the country very little competitive sport Manager London and in so doing Dulwich became one of the took place during the summer and our reporting very few public schools not to be evacuated for the reflects this. -

Warning: Side Effects

WARNING: SIDE EFFECTS A check-up on the federal health law United States Senate 112th Congress Senator Tom Coburn, M.D. Senator John Barrasso, M.D. March 2012 0 Contents Introduction………………….……………………………………………………………………………………..2 1. Millions of Americans Could Lose Their Health Insurance Plan……………………………...5 2. Hundreds of Billions of Dollars in Tax Hikes………………………………………………………….9 3. New Insurance Rule Increases Costs, Reduces Choices…………………………………………11 4. Data Confirms Law Is a Government-Takeover of Health Care……………………………...16 5. Findings from New Taxpayer-Funded Research Institute Could Be Used to Deny Payment for Patients’ Care………………………………………………20 6. New Medicare Bureaucracy Empowered………………….………………………………………...27 7. New CO-Ops Expected to Waste Taxpayers’ Dollars…………………………………………….30 8. Device Tax Stifles Innovation…………………………………………………………………………..…34 1 Introduction Two years ago, supporters of the President’s health care law said Congress needed to pass the health bill so the American people could find out what was in it.1 After the President signed the bill into law, supporters guaranteed that “as people learn about the bill….it’s going to become more and more popular.”2 Over the past twenty four months, American families have learned more about the President’s health care law and do not like what they see. Higher insurance premiums. A coming state budget-busting Medicaid expansion. Fewer choices. Less freedom and more government interference. Cuts to Medicare by unelected government bureaucrats. Thousands of pages of regulations. An unconstitutional mandate to buy health insurance. Penalties on employers threatening job creation. Billions of dollars in tax hikes and, once fully implemented, $2.6 trillion in new health care spending. -

Living Well Right to the End

1 Special Interest Group for Philosophy and Ethics Living Well Right to the End Rydal Hall, June 26th to 29th, 2017 2 Contents Living Well Right to the End Introduction 4 Peter Wemyss-Gorman Living with the uncertainty of Cancer 6 Karol Sikora Taking Care of the person in chronic illness 20 Sara Booth Creative approaches to palliative care 35 Kate Binnie Living to die 43 Andy Graydon Coming alive at last 52 Jeremy Swayne To let the patient live and die with dignity 57 Sophie-Freda Borge Contemplative care 65 Narapa Steve Johnson Healing while dying 77 Emmylou Rahtz My recent training in hypnosis 87 Tim Johnson Valuing end of life care 90 Peter Bennett Homeward bound 96 Gillian Bartram 3 Editor Peter Wemyss-Gorman Retired Consultant in Pain Medicine Contributors Karol Sikora, Consultant Oncologist and Dean, University of Buckingham Medical School Sara Booth Honorary Consultant in Palliative Care, Cambridge University Hospitals NHS Trust and Associate Lecturer, Cambridge University Kate Binnie Music therapist and teacher of yoga and mindfulness in palliative care Father Andy Graydon Catholic Priest and hospital chaplain, working in palliative care, mental health and chronic pain Jeremy Swayne Retired GP, homoeopathist and Anglican priest Sophie-Freda Borge Nurse Specialist in Anaesthetics and Palliative Care, Norway Narapa Steve Johnson Buddhist Chaplain and Mindfulness Teacher Emmylou Rahtz Associate Research Fellow, Exeter University Tim Johnson Consultant in Pain Medicine, Salford Peter Bennett Retired senior civil servant, Department of Health. Associate Faculty Member. Science Policy Research Unit, Sussex University Gillian Bartlam Hypnotherapist and Psychotherapist. Professional singer 4 Introduction Peter Wemyss-Gorman I first suggested the theme of this meeting to our steering committee last year after I read the wonderful book Being Mortal by Atul Gawande. -

The Economics of Cancer Care Nick Bosanquet and Karol Sikora Frontmatter More Information

Cambridge University Press 978-0-521-18380-2 - The Economics of Cancer Care Nick Bosanquet and Karol Sikora Frontmatter More information The Economics of Cancer Care This book examines the interaction of economics and the delivery of cancer care in the global context. It analyses the causes of tension between those paying for care, those providing the care and those marketing drugs and devices for cancer. The concept and requirement for rationing is examined in different economic environments. As cancer increases in incidence and prevalence, the economics becomes a far more important subject than ever before. Written by a leading health economist and oncologist, this is the first comprehensive book on the eco- nomics of cancer and is a must have for health professionals and policy makers alike. Nick Bosanquet is Professor of Health Policy at Imperial College London, UK, and is Special Advisor to the House of Commons Health Committee. Karol Sikora is Visiting Professor of Cancer Medicine, Imperial College and Dean of the Brunel-Buckingham Medical School. He was formerly Chief of the WHO Cancer Programme. We would like to thank Kate Bosanquet and Gill Miller for editorial assistance – much appreciated. © in this web service Cambridge University Press www.cambridge.org Cambridge University Press 978-0-521-18380-2 - The Economics of Cancer Care Nick Bosanquet and Karol Sikora Frontmatter More information The Economics of Cancer Care Nick Bosanquet Professor of Health Policy Imperial College Karol Sikora Dean, Brunel-Buckingham Medical School -

Alumni E-Magazine

Alumni E-Magazine The University of Buckingham Alumni Office | June 2019 Festival of Higher Education Medical School Awarded GMC Accreditation WELCOME ANNOUNCEMENTS Dear all, This month we have the first Medical School graduation. It seems impossible that four and a half years have gone by since the first intake of medical students. Now, after all their hard work (and the risk they took in joining the first private medical school in more than 200 years) they are able to celebrate their own individual achievements, but also the achievement of accreditation of the Medical School by the General Medical Council (GMC). What a year! Professor Mike Cawthorne, who sadly died just before the first intake of students, would be so proud. Dr Terence Kealey, who was instrumental in setting up the School, will be receiving an Honorary Degree. Professor Karol Sikora, Dean, must be so thrilled that all the hard work in the years prior to the opening of the School now see the fruition of such intense planning. In the next issue there will be photos and a little more background. Also this month we have our “Festival Week”. The Festival of Higher Education (now in its third year) will take place on campus on 26 and 27 June (with a marquee set up on Beloff Lawn for the whole week). Please see the next page for information on who is speaking and how you can obtain tickets. This is followed on 28 June by the Enterprise Festival (EntFest), sponsored by the Peter Jones Foundation, which will see around 1,000 students from all over the country come to Buckingham for their own graduation from the Peter Jones Academy. -

Cancer Diagnostics, Treatment and Prevention the Latest Innovations from the UK and Europe

Supported by Cancer diagnostics, treatment and prevention The latest innovations from the UK and Europe Networking event: 24 October 2007, 1 Great George Street, London Who should attend? Speakers include: Chief Executives, CTOs, CSOs, Directors, Heads and Senior Researchers involved in the areas of oncology Claire Horton diagnostics, drug discovery and therapeutics; as well as senior DTI - FP7UK academics from research institutions within London, South East and the East. Richard Sullivan Cancer Research UK Benefits of attending: • GAIN an overview of the latest cancer research and funding Chris Buckley opportunities through FP7 GE Healthcare • LEARN ABOUT cutting-edge technological developments in Karol Sikora cancer diagnostics and surgery Imperial College School • DETERMINE new technologies for cancer drug discovery of Medicine • DISCOVER emerging cancer treatment and prevention Michelle Penny technologies Pfizer • EVALUATE the available opportunities for collaborative research and partnerships between industry and academia Stephen Ward Onyvax About us Clive Morris London Technology Network is a not-for-profit organisation. We Astrazeneca help companies succeed through technology-intensive innovation. Chas Bountra GlaxoSmithKline Supported by Neil Thompson Astex For further information, contact [email protected] © LTN 2007 programme may be subject to change Cancer diagnostics, treatment and prevention The latest innovations from the UK and Europe 24 October 2007, 1 Great George Street, London 8.45 Event registration 10.35 Investigating -

Tribune 25 Template V2009

C M C M Y K Y K WEATHER TRY OUR DOUBLE FILET-O-FISH ANY TIME...ANY PLACE, WE’RE #1 HIGH 88F The Tribune LOW 75F T-STORM IN SPOTS BAHAMAS EDITION www.tribune242.com Volume: 105 No.256 TUESDAY, SEPTEMBER 29, 2009 PRICE – 75¢ (Abaco and Grand Bahama $1.25) Choosing CARS FOR SALE, Honour for S E S the right E R T D HELP WANTED I U R S T O ‘SEA WOLF’ N A P I AND REAL ESTATE E Relationships S F SEE WOMAN SECTION BAHAMAS BIGGEST SEE PAGE NINE TRAVOLTA TRIAL: Women charged WEEK TWO ‘Bridgewater’s meeting with Travolta lawyer in pilot murder secretly recorded’ f f FORMER PLP a t Defendants aged 20 and 19 in court s Senator Pleasant e n Bridgewater and u b former premedic i r T Tarino / e Lightbourne Pair also accused of attempted murder k r a lawyer Carlson l C By NATARIO McKENZIE Shurland m Tribune Staff Reporter i yesterday. [email protected] T By NATARIO TWO young women McKENZIE charged with the murder of Tribune Staff Reporter Bahamasair pilot Lionel [email protected] McQueen were arraigned in Magistrate’s Court yesterday. AN attorney for Hollywood celebrity John Travolta Genear McKenzie, 20, of allowed police to set up recording devices in his hotel Warren Street alias “Nettie”, room for a meeting with former PLP Senator Pleasant and Rhonda Knowles, 19, of Bridgewater, it was revealed in court Monday. Winton Estates, alias “Ganja Bridgewater and former ambulance driver Tarino Baby”, have been charged with the murder of McQueen, SEE page 12 29. -

BOCC MEETING PUBLIC COMMENTS 11/18/2020 These Are Questions and Comments Received Through the County Website and Through the Strategic Communications Email

BOCC MEETING PUBLIC COMMENTS 11/18/2020 These are questions and comments received through the County website and through the Strategic Communications email. Name: Carol Knolla Contact Information: [email protected] Received By: This comment was received through the online website. Subject: COVID restrictions Comment: “Numbers continue to rise! Obviously the restrictions in place are not working! Tighten restrictions, please” Name: Steve R. Contact Information: [email protected] Received By: This comment was received through the online website. Subject: Covid Treatments Comment: “I would like Dr. Minns to speak as to what the hospitals and doctors are currently doing and using in treating COVID. Are they even treating at all? Should they began early treatment with therapeutics in the early stage before hospitalization is required. (https://www.trialsitenews.com/this-doctor-has-covid-he-has-a- plan-for-all-of-us/)” Name: Shelley Palmer Contact Information: [email protected] Received By: This comment was received through the online website. Subject: COVID and it’s effects on my business Comment: “I have been doing everything to stay open and keep a much needed service around. Not only for the 18 people on my staff but for the children and families I serve. I had my first positive case last week in nine months. A person behind a desk told me that 12 children and three teachers could not come back for 14 days. They could not come back with a negative test result and most of them had no symptoms. I was able to still pay my teachers thanks to tax credit and some of my parents are choosing to help with tuition.