The Psychological and Human Brain Effects of Music in Combination with Psychedelic Drugs

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Annual Report 2018 -2019

ANNUAL REPORT 2018 -2019 the beckley foundation annual report CONTENTS ABOUT THE FOUNDATION UPCOMING RESEARCH 1 1 3 MESSAGE FROM THE DIRECTOR SCIENTIFIC PUBLICATIONS 2 14 UN SUSTAINABILITY GOALS DRUG POLICY REFORM 3-4 15-18 ADVISORY BOARD ACCESS 5-6 19 SCIENCE EVENTS & MEDIA BECKLEY/BRAZIL 7-8 20-22 BECKLEY/IMPERIAL FUNDING 9-10 22 BECKLEY/MAASTRICHT COLLABORATIONS 11-12 23 BECKLEY/ICEERS THANK YOU 12 24 11 ABOUT THE BECKLEY FOUNDATION Mission Our aim is to harness the power of science in order to integrate psychoactive substances into society as safe & effective tools to treat a broad range of health conditions and to enhance wellbeing. Amanda Feilding Amanda Feilding has been studying the mechanisms underlying the effects of psychedelics since 1966. In 1998, she set up the Beckley Foundation in order to open up the doors of scientific research into the potential benefits of psychedelics, and to develop a scientific evidence base to help reform global drug policies, so that these compounds can be made available to patients in need. The Three Pillars of the Beckley Foundation Science Policy Access The Beckley Foundation’s The Policy Programme Access provides Scientific Programme, provides a rigorous, Amanda Feilding with led by Amanda Feilding, independent review a platform to deliver develops and conducts of current global drug on her goal to develop psychedelic research policies, and for over innovative solutions through an international 20 years has been that ensure psychedelic network of collaborative developing a scientific treatments are made partnerships with leading evidence-base on available for those in scientists and institutions which to build balanced need, in the years ahead. -

From Sacred Plants to Psychotherapy

From Sacred Plants to Psychotherapy: The History and Re-Emergence of Psychedelics in Medicine By Dr. Ben Sessa ‘The rejection of any source of evidence is always treason to that ultimate rationalism which urges forward science and philosophy alike’ - Alfred North Whitehead Introduction: What exactly is it that fascinates people about the psychedelic drugs? And how can we best define them? 1. Most psychiatrists will define psychedelics as those drugs that cause an acute confusional state. They bring about profound alterations in consciousness and may induce perceptual distortions as part of an organic psychosis. 2. Another definition for these substances may come from the cross-cultural dimension. In this context psychedelic drugs may be recognised as ceremonial religious tools, used by some non-Western cultures in order to communicate with the spiritual world. 3. For many lay people the psychedelic drugs are little more than illegal and dangerous drugs of abuse – addictive compounds, not to be distinguished from cocaine and heroin, which are only understood to be destructive - the cause of an individual, if not society’s, destruction. 4. But two final definitions for psychedelic drugs – and those that I would like the reader to have considered by the end of this article – is that the class of drugs defined as psychedelic, can be: a) Useful and safe medical treatments. Tools that as adjuncts to psychotherapy can be used to alleviate the symptoms and course of many mental illnesses, and 1 b) Vital research tools with which to better our understanding of the brain and the nature of consciousness. Classifying psychedelic drugs: 1,2 The drugs that are often described as the ‘classical’ psychedelics include LSD-25 (Lysergic Diethylamide), Mescaline (3,4,5- trimethoxyphenylathylamine), Psilocybin (4-hydroxy-N,N-dimethyltryptamine) and DMT (dimethyltryptamine). -

Ritualized Peyote Use Can Facilitate Mental Health, Social Solidarity

Ritualized Peyote Use Can Facilitate Mental Health, Social Solidarity, and Cultural Survival: A Case Study of the Religious and Mystical Experiences in the Wixárika People of the Sierra Madre Occidental The Harvard community has made this article openly available. Please share how this access benefits you. Your story matters Citation Luce, Nathan William. 2020. Ritualized Peyote Use Can Facilitate Mental Health, Social Solidarity, and Cultural Survival: A Case Study of the Religious and Mystical Experiences in the Wixárika People of the Sierra Madre Occidental. Master's thesis, Harvard Extension School. Citable link https://nrs.harvard.edu/URN-3:HUL.INSTREPOS:37365056 Terms of Use This article was downloaded from Harvard University’s DASH repository, and is made available under the terms and conditions applicable to Other Posted Material, as set forth at http:// nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:dash.current.terms-of- use#LAA Ritualized Peyote Use Can Facilitate Mental Health, Social Solidarity, and Cultural Survival: A Case Study of the Religious and Mystical Experiences in the Wixárika People of the Sierra Madre Occidental Nathan William Luce A Thesis in the Field of Religion for the Degree of Master of Liberal Arts in Extension Studies Harvard University May 2020 Copyright 2020 Nathan William Luce Abstract This paper examines how the Wixárika, or Huichol, as they are more commonly known to the outside world, have successfully engaged in a decade-long struggle to save their ceremonial homeland of Wirikuta. They have fended off a Canadian silver mining company’s attempts to dig mines in the habitat of their most important sacrament, peyote, using a remarkable combination of traditional and modern resistance techniques. -

Psilocybin Mushrooms Fact Sheet

Psilocybin Mushrooms Fact Sheet January 2017 What are psilocybin, or “magic,” mushrooms? For the next two decades thousands of doses of psilocybin were administered in clinical experiments. Psilocybin is the main ingredient found in several types Psychiatrists, scientists and mental health of psychoactive mushrooms, making it perhaps the professionals considered psychedelics like psilocybin i best-known naturally-occurring psychedelic drug. to be promising treatments as an aid to therapy for a Although psilocybin is considered active at doses broad range of psychiatric diagnoses, including around 3-4 mg, a common dose used in clinical alcoholism, schizophrenia, autism spectrum disorders, ii,iii,iv research settings ranges from 14-30 mg. Its obsessive-compulsive disorder, and depression.xiii effects on the brain are attributed to its active Many more people were also introduced to psilocybin metabolite, psilocin. Psilocybin is most commonly mushrooms and other psychedelics as part of various found in wild or homegrown mushrooms and sold religious or spiritual practices, for mental and either fresh or dried. The most popular species of emotional exploration, or to enhance wellness and psilocybin mushrooms is Psilocybe cubensis, which is creativity.xiv usually taken orally either by eating dried caps and stems or steeped in hot water and drunk as a tea, with Despite this long history and ongoing research into its v a common dose around 1-2.5 grams. therapeutic and medical benefits,xv since 1970 psilocybin and psilocin have been listed in Schedule I of the Controlled Substances Act, the most heavily Scientists and mental health professionals criminalized category for drugs considered to have a consider psychedelics like psilocybin to be “high potential for abuse” and no currently accepted promising treatments as an aid to therapy for a medical use – though when it comes to psilocybin broad range of psychiatric diagnoses. -

Drone Music from Wikipedia, the Free Encyclopedia

Drone music From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia Drone music Stylistic origins Indian classical music Experimental music[1] Minimalist music[2] 1960s experimental rock[3] Typical instruments Electronic musical instruments,guitars, string instruments, electronic postproduction equipment Mainstream popularity Low, mainly in ambient, metaland electronic music fanbases Fusion genres Drone metal (alias Drone doom) Drone music is a minimalist musical style[2] that emphasizes the use of sustained or repeated sounds, notes, or tone-clusters – called drones. It is typically characterized by lengthy audio programs with relatively slight harmonic variations throughout each piece compared to other musics. La Monte Young, one of its 1960s originators, defined it in 2000 as "the sustained tone branch of minimalism".[4] Drone music[5][6] is also known as drone-based music,[7] drone ambient[8] or ambient drone,[9] dronescape[10] or the modern alias dronology,[11] and often simply as drone. Explorers of drone music since the 1960s have included Theater of Eternal Music (aka The Dream Syndicate: La Monte Young, Marian Zazeela, Tony Conrad, Angus Maclise, John Cale, et al.), Charlemagne Palestine, Eliane Radigue, Philip Glass, Kraftwerk, Klaus Schulze, Tangerine Dream, Sonic Youth,Band of Susans, The Velvet Underground, Robert Fripp & Brian Eno, Steven Wilson, Phill Niblock, Michael Waller, David First, Kyle Bobby Dunn, Robert Rich, Steve Roach, Earth, Rhys Chatham, Coil, If Thousands, John Cage, Labradford, Lawrence Chandler, Stars of the Lid, Lattice, -

Cannabis and Psychedelics 2016(PDF)

THE BECKLEY FOUNDATION Cannabis and Psychedelics Exploring Consciousness Pioneering Research Changing Minds The Psychedelic Renaissance Since the mid-60s, the Beckley Foundation’s founder and Executive Director Amanda Feilding has had a profound interest in what changes in cerebral circulation and brain function underlie different states of consciousness. To this end, she developed collaborations with leading scientists around the world, and began initiating and directing ground-breaking academic research on psychedelics and their mechanisms of action. Results have paved the way to a better understanding of consciousness and towards therapeutic applications for mental health conditions, especially those that rest on ‘inflexible and excessively organised’ patterns of brain activity, such as depression, anxiety, addiction, and PTSD. The Beckley/Imperial Research Programme Collaboration between Amanda Feilding and Prof David Nutt (Co-Directors of the Programme) at Imperial College London Our comprehensive collaborative Programme uses the latest developments in brain imaging technology and analysis methods to measure brain blood flow, functional connectivity, and neural oscillations (rhythmical activity or ‘brain waves’) during the psychedelic experience. For the first time the brain on LSD has been revealed. Our previous studies were pioneering in capturing the patterns of brain network connectivity on psilocybin and MDMA. The data affirmed the importance of the Default Mode Network (DMN) as the mechanism underpinning the ‘ego’ and illustrated the consistent principles of the psychedelic state: disintegration (loss of integrity within networks) and de-segregation (increased connectivity between networks), creating a looser state of consciousness. Our brain imaging studies with psilocybin revealed that the stream of conscious experience that characterises the psychedelic state appears more fluid and dynamic, as well as showing a global decrease in cortical activation. -

CLINICAL STUDY PROTOCOL Psilocybin-Assisted Psychotherapy

CLINICAL STUDY PROTOCOL Psilocybin-assisted Psychotherapy in the Management of Anxiety Associated With Stage IV Melanoma. Version: Final IND: [79,321] SPONSOR Multidisciplinary Association for Psychedelic PRINCIPAL INVESTIGATOR Sameet Kumar Ph.D. MEDICAL MONITOR Michael C. Mithoefer MD. STUDY PERSONNEL XXXXXXXXXXXXX XXXXXXXXXXXXX XXXXXXXXXXXXX STUDY MONITOR [CRA] Valerie Mojeiko IRB Study Site IRB Sponsor Signatory Rick Doblin Ph.D. Study Period 2008 For trial related emergencies please contact: Dr. Michael Mithoefer MAPS: S Kumar PI Clinical Study Protocol PCA1 Final December 1, 2007 Confidential Page 2 of 83 Table of Contents Introduction......................................................................................................................... 4 Background..................................................................................................................... 4 Disease History and Related Research ........................................................................... 5 Rationale ......................................................................................................................... 7 Summary......................................................................................................................... 7 Ethics................................................................................................................................... 8 Informed Consent of Subject .......................................................................................... 9 Recruitment and Screening............................................................................................ -

The Psychedelic Experience: the Importance of ‘Set’ and ‘Setting’

The Psychedelic Experience: The Importance of ‘Set’ and ‘Setting’ Matthew Nour & Jacob Krzanowski Matthew Nour, CT1 in Psychiatry, South London and Maudsley NHS Foundation Trust; Jacob Krzanowski, CT1 in Psychiatry, South London and Maudsley NHS Foundation Trust. Email: [email protected] *Both authors contributed equally to this work We welcome the renewed interest in the therapeutic potential of psychedelic compounds. In their recent editorial, Sessa and Johnson1 echo the fervent research climate surrounding psychedelics spanning the 1950s and 60s. They suggest that psychedelics may cause prolonged changes in subjects’ personalities and attitudes following mystical-spiritual experiences. This unique and exciting potential mechanism of action certainly warrants the current renaissance in psychedelic research, and has important implications for study design and subject selection. As we move towards re-exploring the clinical applications of psychedelics, however, we must appreciate that the phenomenology of the psychedelic experience is likely to depend not only on a drug’s pharmacodynamic properties, but also on the makeup of the subject (‘set’) and the environmental context (‘setting’) in which the drug is administered. Recent work suggests that the potential importance of ‘set’ in the psychedelic experience should not be overlooked. Hallucinogenic compounds act via the serotonergic 5-HT2A receptor to effect experience and behaviour. Genetic and neuroimaging evidence suggests that inter-subject differences in serotonergic neurotransmission -

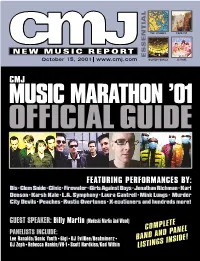

Complete Band and Panel Listings Inside!

THE STROKES FOUR TET NEW MUSIC REPORT ESSENTIAL October 15, 2001 www.cmj.com DILATED PEOPLES LE TIGRE CMJ MUSIC MARATHON ’01 OFFICIALGUIDE FEATURING PERFORMANCES BY: Bis•Clem Snide•Clinic•Firewater•Girls Against Boys•Jonathan Richman•Karl Denson•Karsh Kale•L.A. Symphony•Laura Cantrell•Mink Lungs• Murder City Devils•Peaches•Rustic Overtones•X-ecutioners and hundreds more! GUEST SPEAKER: Billy Martin (Medeski Martin And Wood) COMPLETE D PANEL PANELISTS INCLUDE: BAND AN Lee Ranaldo/Sonic Youth•Gigi•DJ EvilDee/Beatminerz• GS INSIDE! DJ Zeph•Rebecca Rankin/VH-1•Scott Hardkiss/God Within LISTIN ININ STORESSTORES TUESDAY,TUESDAY, SEPTEMBERSEPTEMBER 4.4. SYSTEM OF A DOWN AND SLIPKNOT CO-HEADLINING “THE PLEDGE OF ALLEGIANCE TOUR” BEGINNING SEPTEMBER 14, 2001 SEE WEBSITE FOR DETAILS CONTACT: STEVE THEO COLUMBIA RECORDS 212-833-7329 [email protected] PRODUCED BY RICK RUBIN AND DARON MALAKIAN CO-PRODUCED BY SERJ TANKIAN MANAGEMENT: VELVET HAMMER MANAGEMENT, DAVID BENVENISTE "COLUMBIA" AND W REG. U.S. PAT. & TM. OFF. MARCA REGISTRADA./Ꭿ 2001 SONY MUSIC ENTERTAINMENT INC./ Ꭿ 2001 THE AMERICAN RECORDING COMPANY, LLC. WWW.SYSTEMOFADOWN.COM 10/15/2001 Issue 735 • Vol 69 • No 5 CMJ MUSIC MARATHON 2001 39 Festival Guide Thousands of music professionals, artists and fans converge on New York City every year for CMJ Music Marathon to celebrate today's music and chart its future. In addition to keynote speaker Billy Martin and an exhibition area with a live performance stage, the event features dozens of panels covering topics affecting all corners of the music industry. Here’s our complete guide to all the convention’s featured events, including College Day, listings of panels by 24 topic, day and nighttime performances, guest speakers, exhibitors, Filmfest screenings, hotel and subway maps, venue listings, band descriptions — everything you need to make the most of your time in the Big Apple. -

Psychedelics in Psychiatry: Neuroplastic, Immunomodulatory, and Neurotransmitter Mechanismss

Supplemental Material can be found at: /content/suppl/2020/12/18/73.1.202.DC1.html 1521-0081/73/1/202–277$35.00 https://doi.org/10.1124/pharmrev.120.000056 PHARMACOLOGICAL REVIEWS Pharmacol Rev 73:202–277, January 2021 Copyright © 2020 by The Author(s) This is an open access article distributed under the CC BY-NC Attribution 4.0 International license. ASSOCIATE EDITOR: MICHAEL NADER Psychedelics in Psychiatry: Neuroplastic, Immunomodulatory, and Neurotransmitter Mechanismss Antonio Inserra, Danilo De Gregorio, and Gabriella Gobbi Neurobiological Psychiatry Unit, Department of Psychiatry, McGill University, Montreal, Quebec, Canada Abstract ...................................................................................205 Significance Statement. ..................................................................205 I. Introduction . ..............................................................................205 A. Review Outline ........................................................................205 B. Psychiatric Disorders and the Need for Novel Pharmacotherapies .......................206 C. Psychedelic Compounds as Novel Therapeutics in Psychiatry: Overview and Comparison with Current Available Treatments . .....................................206 D. Classical or Serotonergic Psychedelics versus Nonclassical Psychedelics: Definition ......208 Downloaded from E. Dissociative Anesthetics................................................................209 F. Empathogens-Entactogens . ............................................................209 -

An Update from the Beckley Foundation AMANDA FEILDING

MAPS Bulletin Annual Report Reforming Psychedelic Science and Policy: An Update from the Beckley Foundation AMANDA FEILDING Amanda Feilding THE BECKLEY FOUNDATION HAS HAD a very successful year, with that the changes in connectivity between brain regions brought much progress on our dual fronts of Science and Policy. about by psilocybin resemble those seen during meditation and In January the Beckley Foundation–Imperial College Psy- early psychosis: The networks responsible for inner focus and chedelic Research Programme published two ground-breaking external attention, normally acting in opposition to one another, scienti!c papers on the e"ects of psilocybin on cerebral blood become more closely coupled. This can result in a blurring #ow and brain activity, using brain-imaging technology corre- between “inner” and “outer” worlds in all these states—for lated with subjective reports. The !ndings reveal how psilocybin example the “ego-dissolution” and “unitary state of awareness” decreases blood #ow and thereby diminishes the activity of a reported both after taking psychedelics and in the mystical state. network of key “hub centres,” which are responsible for !lter- Another Beckley/Imperial study, into the neural basis of ing and coordinating information. By decreasing this censoring the e"ects of MDMA, was televised in September on Channel 4 activity, psilocybin allows a freer, less constrained state of con- in the UK and watched by over two million people. In response sciousness to emerge. to positive memories, MDMA was found to increase the response One of the “hubs” deprived of blood #ow by psilocybin is of the brain’s sensory cortex. -

Ecstasy and Club Drugs

Ecstasy and Club Drugs The term “club drug” refers to drugs being used by youth and young adults at all-night dance parties such as “raves” or “trances,” dance clubs and bars. MDMA (Ecstasy), GHB, Rohypnol, Ketamine, Methamphetamine, and LSD are among the drugs referred to as “club drugs.” “Raves” are a form of dance and recreation that is held in a clandestine location with fast-paced, high-volume music, a variety of high-tech entertainment and usually the use of “club drugs.” Ecstasy Ecstasy or MDMA (methylenedioxymethamphetamine) is a stimulant that combines the properties of methamphetamine or “speed” with mind-altering or hallucinogenic properties. It is considered to be the most commonly used club (or “designer” drug). Ecstasy is an illegal drug (it was declared illegal by the federal government in 1985) 90% of which is manufactured in the Netherlands and Belgium. In its most common form, Ecstasy is a small tablet that is impressed with any one of a number of logos intended to attract young people. It can also be in capsule or powder form and can be injected. Among the street names for Ecstasy are Adam, X-TC, Clarity, Essence, Stacy, Lover’s Speed, Eve, etc. The Ecstasy high can last from 6 to 24 hours, with the average “trip” lasting only about 3-4 hours. Users of Ecstasy report that it causes mood changed and loosens their inhibitions; they become more outgoing, empathetic and affectionate. For this reason, Ecstasy has been called the “hug drug.” It also suppresses the need to eat, drink or sleep, enabling users to endure parties that can last for two or three days.