The Perfect Storm

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Perfect Storm October 1991

Satellite Gallery / Extratropical Cyclones / Perfect Storm 1991 / The Perfect Storm October 1991 Enlarged Image Image Information Event Discussion Bizarre Ending An enormous extratropical low is creating havoc along the entire Eastern Atlantic Seaboard in this infrared image at 1200 UTC (0700 EST) on October 30, 1991. Labelled the "perfect storm" by the National Weather Service, the storm s ank the swordfishing boat Andrea Gail, whose story became the basis for the currently best-selling novel "The Perfect Storm" by Sebastian Junger. A little-known and bizarre ending came to this monster, which came to be known as the Halloween Storm. To tell this incredible story in its entirety, the Satellite's Eye Art Gallery spans two subject headings (Extratropical Cyclones and Hurricanes)! Image Information Satellite System Image Specifics Channel Satellite Name GOES 7 No. 4 (Infrared) Band October 30, Date Resolution 4-km 1991 Julian Date 303 Orbit No./Dir NA 1201 UTC Time Entity ID NA 0701 EST Instrument Western VAS: VISSR Area System Atlantic Data Type Sector The Perfect Storm Conditions at the Time of the Image The color-enhanced infrared image of 1200 UTC October 30, 1991 depicts a monster storm off the Eastern Sea board, which was described by the National Weather Service as the "perfect storm." In this image, the storm was at its peak intensity. The storm became subtropical thirty hours later, just before the inner core of the storm developed into a topical storm and later an unnamed hurricane. History of the Storm Late October and November are months with weather in rapid transition in the eastern U.S. -

Table of Contents

Commonwealth of Massachusetts 2013 State Hazard Mitigation Plan Section 13. Nor’easters .......................................................................................................................... 13-1 13.1 General Background .................................................................................................................. 13-1 13.1.1 Rating Scales ................................................................................................................ 13-2 13.1.2 Coastal Storm Frequency Caveats ................................................................................ 13-3 13.2 Hazard Profile ........................................................................................................................... 13-4 13.2.1 Location........................................................................................................................ 13-4 13.2.2 Previous Occurrences ................................................................................................... 13-4 13.2.3 Probability of Future Occurrences ............................................................................... 13-9 13.2.4 Severity ........................................................................................................................ 13-9 13.2.5 Warning Time .............................................................................................................. 13-9 13.3 Climate Change Impacts .......................................................................................................... -

Geology Combination of Storms Precursors

Geology !Hurricanes: violent warm core tropical storm and min wind speed of 74 mph. Rotates counterclockwise spiraling around region of low pressure (eye/center) !June 1- November 30 !Saffir-Simpson Hurricane Scale (1-5) !4 Stages of Hurricane Growth: Tropical Jennifer Lougen Disturbance, Tropical Depression, Tropical Storm, Hurricane Natural Hazards & Disasters October 19, 2005 !Nor’easter: east moving cold air meets warm air from Eastern Atlantic Coast Combination of Storms region !snow, rain, freezing rain, and sleet !strong winds !significant coastal flooding !blizzard conditions !Hybrid Storm: special type of coastal storm that can produce major problems in the fall; combined char. Of tropical & extratropical/midlatitude storms October 28, 1991 Precursors !Subtropical storm E. Caribbean reaches hurricane status !Hurricane Bob, August 1991 (Hurricane Grace) !Extratropical storm !Hurricane Grace, October 28, 1991 off of New England October 29, 1991 !Strong Extratropical !Hurricane Grace Storm changed direction !Area of Low Pressure (ENE) !Extratropical storm absorbed Hurricane Grace 1 October 30, 1991 November 1, 1991 (4 pm) !Peak winds (~ 100 mph) ! 100 ft. waves (one of highest ever recorded) !10-30 ft. waves hitting coast !Extratropical Storm turned SW"S November 1, 1991 (6 pm) !Over Warm Gulf !Tropical Storm intensity Stream !Late, eye forming ! hit New England (almost hurricane status) Coast October 31, 1991 !November 2: !Makes counterclockwise loop !Winds ~ 100 mph !Hurricane Status !Cyclone weakened !Landfall near Halifax, Nova Scotia !Dissipated 10 hours later Preparation & Awareness After Effects ! Storm not thought !New England storms commonly from of as real threat to West land but more to ships !Perfect storm came from East ! Beach Erosion ! NWS, local meteorologists and (10’s m’s removed Hurricane Ctr. -

Summer-Fall 2006 Newsletter.Pub

NOAA’S NATIONAL WEATHER SERVICE, NEWPORT/MOREHEAD CITY NC www.erh.noaa.gov/mhx - BOOKMARK IT! CAROLINA SKY WATCHER SUMMER 2006 EDITION Hurricane Season 2006 Outlook By John Cole, Warning Coordination Meteorologist 2006 is expected to be another active year for tropical cyclones in the Atlantic Hurricane Basin. NOAA expects 13-16 named storms, 8-10 hurri- canes (sustained winds greater than 74 mph), and 4-6 major hurricanes (sustained winds over 110 mph). Dr. William Gray and his research team at Colorado State University expect 17 named storms, 9 hurricanes, and 4 major hurricanes. Dur- ing an average hurricane season, which runs from June 1st through Nov. 30th, we have 11 named storms, 6 hurricanes, and 2 major hurricanes. Fac- tors which favor an active year are warmer than normal water temperatures, light mid and upper level winds, and lower pressure in the Atlantic Ocean, Caribbean Sea, and the Gulf of Mexico. The three primary months for hurricane activ- ity are August, September, and October. INSIDE THIS ISSUE: HURRICANE THREAT- 2 TORNADOES HURRICANE FRAN-10 YEARS 3-4 AGO HURRICANE QUIZ 5-6 SAFFIR WHO? SIMPSON WHO? 7 RIP CURRENT DANGER 8-9 PAGE 2 CAROLINA SKY WATCHER Hurricane threats: tornadoes! By Bob Frederick, Forecaster Hurricanes pose many threats to life and property when they impact eastern North Carolina. Across the United States approximately 10 percent of hurricane fatalities are a result of tornadoes. Some hurricanes and tropical storms produce little if any tornado activity, while other can produce numerous tornadoes. Almost all tornadoes associated with hurricanes occur on the right front quadrant of the storm (see Figure 1). -

Hurricanes - General Information for Bermuda Prepared by the Bermuda Weather Service – Updated August 2021

Hurricanes - General Information for Bermuda Prepared by the Bermuda Weather Service – updated August 2021 Hurricanes and tropical storms have had an impact on Bermuda from its earliest times. The initial colonization of Bermuda was a direct result of a hurricane in 1609 in which an English ship the "Sea Venture" ran aground. A study of local records from 1609 to the present day, of storm damage through the years indicates a damaging storm once every 6 to 7 years until the 21st century. Since 2000, an uptick in Bermuda-relevant tropical cyclones (TCs) has been noted in the record, and highlighted in the academic literature. The long-term effects of climate change on the variability of Bermuda TCs are an area of active research. However, recent studies indicate that increasing upper ocean temperatures near Bermuda are contributing to increased trends in TC activity locally. Hurricane season in the Atlantic is June through November, however Bermuda has seen subtropical storm activity as early as April (e.g. 2003 Ana), and has occasionally experienced tropical cyclone activity through November. Bermuda is 54 square kilometres (21 sq. miles) in area, located approximately at 32.3°N 64.7°W. Despite being out of the main TC development region of the tropical Atlantic, as well as being a ‘small target’, Bermuda has received a number of notable TC impacts in the last 20 years. The peak months for tropical cyclone activity for Bermuda are September and October, with over 80% of all storms coming within ‘threat’ range (100nm/185km) of Bermuda occurring during these months. -

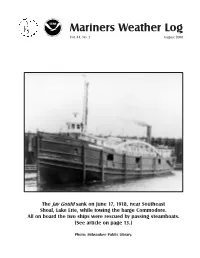

Mariners Weather Log Vol

Mariners Weather Log Vol. 44, No. 2 August 2000 The Jay Gould sank on June 17, 1918, near Southeast Shoal, Lake Erie, while towing the barge Commodore. All on board the two ships were rescued by passing steamboats. (See article on page 13.) Photo: Milwaukee Public Library. Mariners Weather Log Mariners Weather Log From the Editorial Supervisor This issue features an article on storm surge, which is the term used to describe the rise in still-water sea level that accompanies the landfall of a tropical storm or hurricane. Recognized as the single most destructive aspect of a hurricane, the coastal storm surge can cause much damage and loss of life (nine out of ten hurricane U.S. Department of Commerce deaths result from drowning in storm surge). The low Norman Y. Mineta, Secretary pressure in the eye literally sucks the ocean surface upward, like liquid through a straw, and vast tracts of National Oceanic and low-lying coastal terrain can be inundated with water as Atmospheric Administration the eye of the hurricane makes landfall. In the northern Dr. D. James Baker, Administrator hemisphere, the area just to the right of the storm track experiences the greatest rise in water level due to the added effect of the wind pushing the water. During the National Weather Service John J. Kelly, Jr., infamous hurricane Camille in 1969, a 25-foot storm Assistant Administrator for Weather Services surge inundated Pass Christian, Mississippi. Lesser heights are more usual, but still extremely dangerous. Editorial Supervisor Directly linked to a tropical storm’s central barometric Martin S. -

Seed Groups Process

Exploring the Scriptures June 24, 2012 Mark 4:35-41 Storms and Calm by Blair Odney In his book, “The Perfect Storm,” Sebastian Junger recounts the story of a natural disaster off the coast of Massachusetts in the fall of 1991. In 2000, the book became a movie starring George Clooney. The death toll was 13 and damage was estimated at $200 million, most which occurred when waves up to 10 meters struck the coastline from Canada to Florida and down to Puerto Rico. A buoy off the coast of Nova Scotia reported a wave height of 30 meters, the highest ever recorded in the province's offshore waters...basically the height of ten story building. Imagine meeting a wall of water 100 feet high.. So what made this storm so “perfect”? Junger got the phrase “perfect storm” from a retired meteorologist who said the storm’s intensity was caused by a perfect alignment of several factors; such a convergence of weather conditions occurs only once every 50 to 100 years. This perfect storm began on October 26, with the formation of a hurricane, a Category 2 tropical storm south of Bermuda. This hurricane moved up the East Coast of the United States, losing power along the way, but on October 29, it collided with a cyclone moving down the coast from Nova Scotia. The cyclone, formed by a low-pressure front moving in from the Midwestern United States met a high-pressure front moving down from Northern Canada, which together absorbed the power of the first hurricane, increasing in intensity. -

Perfect Storm

THE PERFECT STORM DEVELOPS 0. THE PERFECT STORM DEVELOPS - Story Preface 1. THE ANDREA GAIL 2. LONG-LINING for SWORDFISH 3. PREDICTING BAD WEATHER 4. PREDICTING DANGEROUS STORMS 5. THE PERFECT STORM DEVELOPS 6. DEATH ON THE HIGH SEAS 7. ANOTHER MAELSTROM 8. RESCUE EFFORTS AT SEA 9. THE UNNAMED HURRICANE 10. NEIGHBORS IN DEATH Three different weather systems collided between the 28th of October and the 2nd of November - in 1991 - to produce what meteorologists called a "perfect storm." Graphic online, courtesy AccuWeather. On October 23, 1991, Billy Tyne and his crew (Michael "Bugsy" Moran, Dale "Murph" Murphy, Alfred Pierre, David Sullivan and Bobby Shatford) set their longline for what they hoped would be the best catch of the trip. (The links take you on board the Andrea Gail the year before she was lost. The fish hold is empty in the picture.) It was the last full moon of the fishing season, and the men would soon be steaming home to Gloucester. As the Andrea Gail headed home, most of the other boats in the fleet were hundreds of miles east - still fishing. When Billy radioed the Canadian Coast Guard the afternoon of October 27th, to let them know his boat was inside Canada's territorial waters, he didn't know a huge storm was brewing south of him. (The link takes you inside the pilot house of the Andrea Gail.) He didn't know until he received the first fax, later that night. What Billy didn't know was that Hurricane Grace, forming off Bermuda on the 27th of October, had turned northeast. -

North Carolina Homeowners Writers Fortunate in Bouts with Hurricane and Tropical Storms

North Carolina Homeowners Writers Fortunate in Bouts with Hurricane and Tropical Storms by Joseph L. Petrelli, ACAS, MAAA, FCA President Demotech, Inc. November 2010 Demotech, Inc. North Carolina Homeowners Writers Fortunate in Bouts with Hurricane and Tropical Storms Earlier in 2010, Colorado State’s Tropical Meteorology Project forecasted eight hurricanes to emerge from fi fteen named tropical storms in the Atlantic basin. Of those, four were forecasted to become major hurricanes. On August 29, Tropical Storm Earl was upgraded to a hurricane and reached Category 4 status. Hurricane Earl headed toward the eastern coast of the United States. As Hurricane Earl rampaged through the Caribbean, federal and state offi cials feared a hurricane reminiscent of 1991’s Hurricane Bob and began preparing to evacuate areas of the coast. Although Hurricane Earl dissipated and there was no major damage to the eastern coast of the United States, North Carolina Governor Beverly Perdue shared the sentiment of many of North Carolina’s residents when she stated that “North Carolina dodged a bullet” when Earl missed the coast. Not long after Earl vacated the area, there were warnings and preparations made for the arrival of Tropical Storm Nicole. The storm brought massive amounts of rain and fl ooding. States of emergency were declared in parts of Florida, North Carolina and as far north as Delaware. Thankfully, Tropical Strom Nicole swept through the region without much damage reported. Again, North Carolina dodged a bullet. In fact, major storm activity from 1980 to date indicates that North Carolina has seen several bullets whiz by (Exhibit 1). -

Extreme Weather, Health, and Communities Interdisciplinary Engagement Strategies Extreme Weather and Society

Extreme Weather and Society Sheila Lakshmi Steinberg William A. Sprigg Editors Extreme Weather, Health, and Communities Interdisciplinary Engagement Strategies Extreme Weather and Society Series editors William A. Sprigg, Tucson, AZ, USA Sheila Lakshmi Steinberg, Irvine, CA, USA Extreme Weather and Society examines people, place and extreme weather, from an emerging trans-disciplinary field of study. The series explores how abrupt and trending changes in weather alter physical environments and force community responses challenged by cultural practices/interpretations, politics, policy, respon- sibilities of education and communication, community health and safety, and environmental sustainability for future generations. The series highlights extreme weather alterations to different physical and social environments to better explore how people react and respond to extreme weather. The hallmark of this series is the innovative combined inclusion of social and physical science expertise. Extreme Weather and Society contains single and multi-authored books as well as edited volumes. Series Editors are currently accepting proposals, forms for which can be obtained from the publisher, Ron Doering ([email protected]). More information about this series at http://www.springer.com/series/15334 Sheila Lakshmi Steinberg • William A. Sprigg Editors Extreme Weather, Health, and Communities Interdisciplinary Engagement Strategies 123 Editors Sheila Lakshmi Steinberg William A. Sprigg School of Arts and Sciences Department of Atmospheric Sciences Brandman University-Chapman University The University of Arizona System Tucson, AZ Irvine, CA USA USA Extreme Weather and Society ISBN 978-3-319-30624-7 ISBN 978-3-319-30626-1 (eBook) DOI 10.1007/978-3-319-30626-1 Library of Congress Control Number: 2016934022 © Springer International Publishing Switzerland 2016 This work is subject to copyright. -

Lynn Donelson Wright C. Reid Nichols Editors Tomorrow’S Coasts: Complex and Impermanent Coastal Research Library

Coastal Research Library 27 Lynn Donelson Wright C. Reid Nichols Editors Tomorrow’s Coasts: Complex and Impermanent Coastal Research Library Volume 27 Series editor Charles W. Finkl, Coastal Education and Research Foundation Boca Raton, FL, USA The aim of this book series is to disseminate information to the coastal research community. The Series covers all aspects of coastal research including but not limited to relevant aspects of geological sciences, biology (incl. ecology and coastal marine ecosystems), geomorphology (physical geography), climate, littoral oceanography, coastal hydraulics, environmental (resource) management, engi- neering, and remote sensing. Policy, coastal law, and relevant issues such as conflict resolution and risk management would also be covered by the Series. The scope of the Series is broad and with a unique cross-disciplinary nature. The Series would tend to focus on topics that are of current interest and which carry some import as opposed to traditional titles that are esoteric and non-controversial. Monographs as well as contributed volumes are welcomed. Charles W. Finkl, Coastal Education & Research Foundation, USA Email: cfi[email protected] More information about this series at http://www.springer.com/series/8795 Lynn Donelson Wright • C. Reid Nichols Editors Tomorrow’s Coasts: Complex and Impermanent A collaborative synthesis promoted by the Coastal and Environmental Research Committee of the Southeastern Universities Research Association (SURA) 123 Editors Lynn Donelson Wright C. Reid Nichols Southeastern Universities Research Marine Information Resources Association (SURA) Corporation (MIRC) Washington, DC Ellicott City, MD USA USA ISSN 2211-0577 ISSN 2211-0585 (electronic) Coastal Research Library ISBN 978-3-319-75452-9 ISBN 978-3-319-75453-6 (eBook) https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-75453-6 Library of Congress Control Number: 2018940873 © Springer International Publishing AG, part of Springer Nature 2019 This work is subject to copyright. -

The Antecedent Large-Scale Conditions of the ''Perfect Storms'' Of

2546 MONTHLY WEATHER REVIEW VOLUME 138 The Antecedent Large-Scale Conditions of the ‘‘Perfect Storms’’ of Late October and Early November 1991 JASON M. CORDEIRA AND LANCE F. BOSART Department of Atmospheric and Environmental Sciences, University at Albany, State University of New York, Albany, New York (Manuscript received 10 November 2009, in final form 26 January 2010) ABSTRACT The ‘‘Perfect Storms’’ (PSs) were a series of three high-impact extratropical cyclones (ECs) that impacted North America and the North Atlantic in late October and early November 1991. The PSs included the Perfect Storm in the northwest Atlantic, a second EC over the North Atlantic that developed from the interaction of the PS with Hurricane Grace, and a third EC over North America commonly known as the ‘‘1991 Halloween Blizzard.’’ The PSs greatly impacted the North Atlantic and North America with large waves, coastal flooding, heavy snow, and accumulating ice, and they also provided an opportunity to investigate the physical processes that contributed to a downstream baroclinic development (DBD) episode across North America that culmi- nated in the ECs. Downstream baroclinic development resulted from an amplification of the large-scale flow over the North Pacific that was influenced by anomalous tropical convection, the recurvature and extratropical transition of western North Pacific Tropical Cyclones Orchid, Pat, and Ruth, and the subsequent evolution of the extra- tropical flow. The progression of DBD occurred following the development of a negative PNA regime and the generation of baroclinic instability over North America associated with equatorward-displaced potential vorticity anomalies and poleward-displaced corridors of high moisture content.