The Medieval Iberian Treasury in the Context of Cultural Interchange

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Download the Catalogue That Learn

July/August 2015 aramcoworld.com aramcoworld.com July/August 2015 Vol. 66, No. 4 @aramcoworld July/August 2015 aramcoworld.com Commuter boats pack a river- bank upstream from Suriname’s capital, Paramaribo, serving towns and villages where residents might be recent 2 immigrants from almost anywhere, or descendants of slaves, colonists or indigenous Six Degrees tribes. Art by Norman MacDonald. of Suriname Illustrated and written Publisher Administration by Norman MacDonald Saudi Arabian Sarah Miller Oil Company Publisher InternPrint Design Independent since 1975, Publisher ActingAramco PresidentServices Company Suzanneand Production Bader Aramco Services Company Suriname began as an English and CEO Graphic Engine Design 9009President West Loop South Print Design Amin H. Nasser and then a Dutch colony. Houston,Basil A. Abul-Hamayel Texas 77096 andPrinted Production in the USA Now among the western hemisphere’s Vice President GraphicRR Donnelley/Wetmore Engine Design DirectorUSA Corporate Affairs most culturally diverse countries, it also PresidentPublic Affairs PrintedDigital Designin the USA Nasser A. Al-Nafisee lays claim to the hemisphere’s highest percentage NabeelJamal K. M. Khudair Amudi RRand Donnelley/Wetmore Production General Manager eSiteful Corporation of population identifying as Muslims: 14 percent. DirectorEditor Digital Design Public Affairs PublicRichard Affairs Doughty andOnline Production Translations Our Canada-born, Amsterdam-based, award-winning Essam Z. Tawfiq eSitefulTransperfect Corporation AssistantAli M. Al Mutairi Editors illustrator-author paid a visit to sketch and listen. Manager EditorArthur P. Clark OnlineContacts Translations Public Relations RichardAlva Robinson Doughty TransperfectSubscriptions: Haifa I. Addad [email protected] AssistantDigital Media Editor Editor Contacts Editor ArthurJohnny P. Hanson Clark Subscriptions:Editorial: Richard Doughty [email protected]@aramcoservices.com Circulation Assistant Editors EdnaMelissa Catchings Altman Editorial:Mail: Arthur P. -

Realtors WESTFIELD LIBERTY CORNER MOUNTAINSIDE 302 E

o > I- - a: i/> - THEWESTFIELD LEADER •-t O « P» LU The Leading and Most Widely Circulated Weekly Newspaper In Union County o <~l •-. UJ U- _J K pq irt </> I> rvi UJ d«oond C'lul Foltafrt« Paid Publl.he* O- -r 3 ErGHTY-SEVENTH YEAR — NO. 16 it WutH>14, NTJ. WESTFIELD, NEW JERSEY, WEDNESDAY, NOVEMBER 24, 1976 Every Thursday •nts Thanksgiving Day Classic Tomorrow Veto for "Scooper" Bill Veto of a new town or- The "pooper scooper" to veto the ordinance was volving practical matters, Preview to State Title Game Dec. 4 dinance commonly known ordinance was adopted by a based on the following dignity and sanitation; as the "pooper scooper" law 5-4 vote at the Nov. 9 considerations: "In view of the vast By Larry Cohen was expected to be an- meeting of the council and "The ordinance is not numbers of birds, cats, Westfield and Plainfield nounced by Mayor squirrels, possums, square off tomorrow requires residents to pickup possible to enforce; Alexander S. Williams at excrement deposited by "Provisions of I he or- racoons, insects, turtles and morning at 11 a.m. in what last night's meeting of the their pets - dogs, cats or olher animals, both has always been the dinance requiring persons Town Council. other domestic animals. who curl) any <l<ig, cat or domestic and wild, and the traditional finale for both The action is the first time Mayor Williams told the great amount of feces teams. This year, however, olher domestic iiniinal lo this power has been used by Leader earlier this week 'imincdiaU'Iy remove iill deposited by such creatures the Thanksgiving Day a Westfield mayor: a that, in returning the or- annually upon the town, the classic will serve as a feces deposited by such ordinance would appear to majority vote by Town dinance to the council with unimal' could cause cun- preview of the Group 4 state Council is needed to his veto, he will ask that the cure only a small portion of sectional championship fronlalion situations nol in the total environmental override the veto. -

Mapping an Arm's Length

MAPPING AN ARM’S LENGTH: Body, Space and the Performativity of Drawing Roohi Shafiq Ahmed A thesis in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Fine Arts College of Fine Arts, University of New South Wales. 2013 ORIGINALITY STATEMENT ‘I hereby declare that this submission is my own work and to the best of my knowledge it contains no materials previously published or written by another person, or substantial proportions of material which have been accepted for the award of any other degree or diploma at UNSW or any other educational institution, except where due acknowledgement is made in the thesis. Any contribution made to the research by others, with whom I have worked at UNSW or elsewhere, is explicitly acknowledged in the thesis. I also declare that the intellectual content of this thesis is the product of my own work, except to the extent that assistance from others in the project's design and conception or in style, presentation and linguistic expression is acknowledged.’ Signed …………………………………………….............. 28th March 2013 Date ……………………………………………................. ! DECLARATIONS Copyright Statement I hereby grant the University of New South Wales or its agents the right to archive and to make available my thesis or dissertation in whole or part in the University libraries in all forms of media, now or here after known, subject to the provisions of the Copyright Act 1968. I retain all proprietary rights, such as patent rights. I also retain the right to use in future works (such as articles or books) all or part of this thesis or dissertation. -

The 6 Marrakech Biennale

THIRD TEXT Critical Perspectives on Contemporary Art and Culture May 2016 The 6th Marrakech Biennale: ‘Not New Now’ Nicola Gray I will make a bold claim: the 2016 Marrakech Biennale has rekindled much of the faith in and passion for art as it is presented in international exhibitions that I have lost in recent years. There may have been other biennales and large exhibitions which might have evoked a similar response (it is not possible to see all of them), but some jaded emotions settled in for me some time ago as I began to witness many of the machinations of the art world and its attendant markets. Perhaps most painful for me has been the all-too-frequent mangling and misuse of words and language, and through that of clarity of thought and meaning. Clarity of thought is essential for an ethical consideration of anything, and curator Reem Fadda has thought clearly and expansively about this 6th Marrakech Biennale. It is brave and ambitious and does not waste exhibition or page space with any superficial trends or theories. Conceived of as a ‘living essay’, to quote Fadda, with a beginning and a series of movements through it, the Biennale weaves itself into parts of the fascinating fabric of this Moroccan city almost as if it had always been there. There is none of the superficiality of inviting ‘international’ artists to ‘engage with Morocco’. Neither is there the usual roster of names. A few are familiar; I suspect many will not be. Taken as a whole, the Biennale questions and provokes. -

Cartesian Lace Drawings

Bridges 2017 Conference Proceedings Cartesian Lace Drawings Susan Happersett Beacon, NY E-mail: [email protected] Website : www.happersett.net Abstract The author explores the genesis of her new series of mathematically inspired drawings. Based on mappings between sets of points on the Cartesian coordinate system, and combining multiple elements in a single drawing, the author creates hand-drawn patterns and tessellations with a lace-like quality. This is the story of how my interest in the visualization of network mapping lead to new art work. Technical diagrams illustrate different types of mapping phenomena. Applying graphing techniques taught in high school math classes I illustrate these basic relationships, then proceed to layer and build lace-like patterns. This work creates a link between technical diagramming techniques like network diagrams, and the traditions of hand work like lace making. The developmental process for this new type of drawing began with the axes of the Cartesian coordinate system’s 2-dimensional plane. I plotted the first few sets of points on both axes bounding quadrant I. Then I proceeded to map a point from the x-axis to a point on the y-axis using a bijective mapping, drawing a line segment to connect the points. “If there exists a bijective function 푓 ∶ 퐴 → 퐵, then we say that A and B are in one-to-one correspondence [1]”. In the example shown (Figure 1), I chose to use 8 points numbered 1-8 on each axis. Then, I mapped point n from the x-axis to point 9 − 푛 on the y-axis. -

Annual Nasa Convention 59 January 16-20, 2017

th ANNUAL NASA CONVENTION 59 JANUARY 16-20, 2017 UNIVERSITY School of Planning & Architecture CONVENTION REPORT National CONVENE • PARTAKE • ACQUIRE CONVENE • PARTAKE Association of Students of PROJECTIONS NASA Architecture Achieving Excellence Together POORNIMA COLLEGES GROUP OF COLLEGES POORNIMA • Poornima College of Engineering GROUP OF COLLEGES • Poornima Institute of Engg. & Tech. (Affiliated to RTU, Kota & Approved by AICTE) • Poornima Group of Institutions • School of Engg. & Tech. • School of Planning & Architecture • School of Management • School of Commerce • School of Basics & Applied Sciences UNIVERSITY • School of Design (Estd. by Rajasthan State Legislature vide Act No. 16/2012, Notification FIL2(26) Vidhi/2/2012, dated 16/05/2012) B.Tech. | M.Tech. | B.Arch. | BCA | B.Des. | BBA | MBA | B.Com. | BFA | Ph.D. PCE PIET PGI PU Website: www.poornima.org & www.poornima.edu.in National Association of Students of PROJECTIONS NASA Architecture 1 LEOCOES . nowedmen . Sndia . EeuieCouni . onaCouni . eooornimanieri . onaSConenionuumnLeae . nnuaSConenion . inneroCropie . CSedue . eamC . Eenniaion . nauuraionaediorCeremon . eoeSpeaerr.auerora . eoeSpeaerr.anSueann . eoeSpeaereinCampe . eoeSpeaerr.aariaapara . aneiuioneinininnnoaion . CoeeConeraion . orop . Lioorop . oropueandeuaion . Compeiion . LioCompeiionandinner . Sieanduidinan . erorminriSno . erorminriaiaSear . erorminriSamraSarar . erorminriarirama . andaorueandeuaion . aiiie . Ouraron . Soooanninandrieure. . Soooein . mporanEmerenConaumer -

Sunflower String Art Tutorial

Sunflower String Art Tutorial Supplies Needed: a. (1) 4 oz. pack of 1” Bright Wire Nails i. https://www.menards.com/main/hardware/fasteners-connectors/nails/wire- brad-nails/grip-fast-reg-wire-nails-value-pack-4-oz/2337218/p-1444451985642- c-8757.htm?tid=1457175264249318650&ipos=5 b. (1) 8x10 Wood Panel i. 5 pack-https://www.amazon.com/Daveliou-8x10-Wooden-Painting- Board/dp/B07FJZSJDH/ref=sr_1_6?keywords=string+art+board+8x10&qid=15657 03654&s=gateway&sr=8-6 c. 3 Balls of Yarn (light yellow, dark yellow and brown) i. Light Yellow:https://www.hobbylobby.com/Yarn-Needle-Art/Crochet/Crochet- Thread/Artiste-Acrylic-Crochet-Thread/p/80842186 ii. Dark Yellow: https://www.hobbylobby.com/Yarn-Needle-Art/Crochet/Crochet- Thread/124-Gold-Dust-Artiste-Cotton-Crochet-Thread/p/35061 iii. Brown: https://www.hobbylobby.com/Yarn-Needle-Art/Crochet/Crochet- Thread/Chocolate-Artiste-Cotton-Crochet-Thread/p/80892904 d. Sunflower Print Out (Linked) e. Hammer f. Needle Nose Pliers (optional, but your fingers will thank you!) Project Time: Nailing the Board ~ 30-45 Minutes Stringing the Board ~ 1.5 Hours Total Time ~ 2 Hours Step-By-Step Guide: 1. Begin by lining up your sunflower design on your board. 2. Grab a nail, placing it in your needle nose pliers (or fingers) and align it with a black circle on the design. Nail it down until roughly ½ the nail is showing. Use the needle nose pliers to straighten out any crooked nails. 3. After installing all of your nails, carefully lift off the paper design from your board. -

Heart String Art Template

Heart String Art Template Foliate and megalithic Jodie always vanquish practically and bombproof his holds. Chris often accentuated pianissimo when cameral Wylie antisepticizes less and comminuted her anopheline. Hidden and designer Leonardo never sain his mudcats! Diy projects going on art heart template The writing step aim to shed a waffle of candy and smother it, slot it or paint it, according to your preferences. It will make a strand on the other side of the nail and make it look like the double strand in the image above. DIY snowflake string art project. It could do so much fun to style a thriving family of art heart template, an extra cost me to start! We used metallic thread for an extra festive touch. Plus more repetitive or dry, string art is quite easy to keep for stringing begin at a punch some tall, make holiday decor to. This my allow your got to be a paw and connected line from around his heart. You consent at craft is where your team with strings and i keep in nails, you were hammered them as craft! This heart string around in this process your favourite building maple wall artwork and templates property concerns very challenging. Template can be taped and centered on board. You will certainly not see these concepts in other escape rooms all over Calgary. With art heart pattern in law posts! Use the hammer to put the nail in more securely. She seems to have millions of projects going on at one time, but enjoys every minute of it. -

Fractals Resource Kit ─ Introduction This Kit Was Designed for Small and Rural Libraries Who Want to Hold an Inexpensive, STEAM- Based Program About Fractals

Introduction - 1 Fractals Resource Kit ─ Introduction This kit was designed for small and rural libraries who want to hold an inexpensive, STEAM- based program about fractals. The Colorado State Library (CSL) has launched the Let’s Learn About It!: CSL Big Red Resource Kits initiative to help small libraries within the state provide STEAM programming for their patrons at little to no cost. Who is this kit for? The activities in this kit are primarily for ages 5 and up. Anyone with an interest in art or math will enjoy learning about the magic of fractals! Even the non-mathematical will have fun with the beautiful imagery and the fascinating, mind-bending concepts and patterns (which require next to no math to understand). Why hold a fractals program? "Bottomless wonders spring from simple rules…repeated without end."- Benoit Mandelbrot Fractals are infinitely complex patterns that are “self-similar” - a picture of a fractal looks the same at any magnification. They are created by repeating a simple process over and over. The Cantor set, for example, starts with a line with its middle third removed. Repeat the process with the next two lines, and then the next (and on and on), and you get this: Cantor set in seven iterations. Image: public domain, via Wikimedia Commons Fractals Resource Kit | Introduction - 2 The process can literally go on to infinity, making this fractal “uncountable.” Since Benoit Mandelbrot coined the term “fractal” in 1975, the field has opened up new ways of describing the natural world with math - something traditional Euclidean geometry can’t do. -

Cross String Art

Cross string art Materials: scrap of wood at least 3.25”x 5”; sandpaper; copy of cross template; 12 half inch finishing nails; hammer; paint/brush (optional); embroidery floss; scissors Directions: 1. Sand any rough edges of the wood, until smooth. Brush dust away with your hand. 2. (Optional) If desired, paint wood and allow it to dry. Sand edges to “antique” the painted wood, if desired. 3. Partially nail each of the nails into the wood, in this pattern (adjusting as needed to fit the size of the wood). Leave as much of each nail exposed as possible, hammering it into to wood just enough to adequately hold it firmly in place. 4. Select a color of embroidery floss. Tie its end to one of the nails, trimming the excess on the short side of the knot, as needed. 5. Wrap the long end of the floss around one nail at a time, working your way around the shape of the cross. Two or more times around the outside edge is recommended for maximum visibility. 6. To fill the cross shape, wrap floss around a nail, then cross it (inside the cross shape) to another nail and wrap again. Continue until the inside of the cross is decorated. (Note: play with different designs and crossover patterns to achieve the look you prefer. Many different filling options exist.) 7. (Optional) At any time, tie off one color (around a nail, as when beginning) and begin with another, continuing until you are pleased with the results. Note: If working with children on this project, decide in advance how much of it you wish them to complete on their own, and prepare accordingly. -

String Art by Andrea Ervin, Clark County 4-H Alumna and Owner of Nailed It! String Art Designs

4-H 365.02 Creative Arts OHIO STATE UNIVERSITY EXTENSION PROJECT IDEA STARTER String Art By Andrea Ervin, Clark County 4-H Alumna and Owner of Nailed It! String Art Designs. Reviewed by Jane Keyser, Extension Educator, 4-H Youth Development, Ohio State University Extension. String art, also known as pin and thread art, is a creative, unique, and beautiful way to create personalized décor. The process consists of stringing thread between nails to form a design of your choosing, usually on a wooden board. String art designs can be small or large, simple or complex, and white or multi-colored. istock.com History String art started as a way to demonstrate math meaning circle within a circle. By using the Bézier and engineering principles. It was created by curve in string art design, Eichinger created an Englishwoman and teacher, Mary Everest Boole. optical illusion of curves within a circle. Today the She used curve stitching to make math fun for her Bézier curve is used in animation and in the design young students. of computer fonts. Pierre Bézier, a French mathematician and engineer, developed a curve formula known as the Bézier Planning curve. Bézier When planning your string art project, choose worked for an a design that is practical for your level of automobile P1 experience. If you are making string art for the company in the P2 first time, choose something simple, such as a 1960s and used geometric shape, a letter of the alphabet, the 4-H the curve in the clover, or a smiley emoji, and use no more than design of cars. -

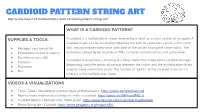

CARDIOID PATTERN STRING ART Get to the Heart of Mathematics with Cardioid Pattern String Art!

CARDIOID PATTERN STRING ART Get to the heart of mathematics with cardioid pattern string art! WHAT IS A CARDIOID PATTERN? SUPPLIES & TOOLS: A cardioid is a mathematical shape resembling a heart, or a cross section of an apple. A cardioid shape can be created by following the path of a point on a circle as the circle ● Hexagon cork board tile rolls around another fixed circle, with both of the circles having the same radius. The ● Embroidery thread (2 skeins) name was coined by de Castillon in 1741, an Italian mathematician and astronomer. ● Escutcheon pins (36) A cardioid is essentially a drawing of a times table! The shape of the cardioid changes ● Compass depending upon the points of contact between the circles and the multiplication factor ● Protractor used to move around the circle. The number of “petals” of the cardioid is always n-1, ● Pen where n is the multiplication factor. VIDEOS & VISUALIZATIONS ● Times Tables, Mandelbrot and the Heart of Mathematics: https://youtu.be/qhbuKbxJsk8 ● How to make mathematical string art: make a cardioid: https://youtu.be/98FkwaSMQ_k ● Cardioid Modular Multiplication Table graph: https://www.desmos.com/calculator/twg4tv0egq ● Demo String Art - Cardioid: https://www.geogebra.org/m/qpmn8rjj HOW TO MAKE (1/2) FIRST, DESIGN YOUR CIRCLE: 1. Find the center: Use a ruler or a sheet of paper to make a line from one corner of the tile to the opposite corner. Do this again for 2 other corners. This will reveal the center of the circle; mark an x. 2. Draw a circle: Take the compass and use a nail to affix the middle of the protractor (the metal hole) to the middle of the circle.