Life in a Welsh Tuberculosis Sanatorium, 1922- 1959

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Mid Wales Abercraf

20 April 2012 Accessibility help Text only BBC Homepage Wales Home Growing up in Abercraf more from this section Neil Hamer grew up in Abercraf Abercraf and still lives their Abercraf In Pictures today. He worked for twelve Children of Craig y Nos - The Book years in Blaenau Colliery in Growing up in Abercraf Creunant and still likes to walk My Town Ogof Ffynon Ddu BBC Local the mountains that were once Pen Portrait - Abercraf Mid Wales plundered for their coal. Science is Golden Things to do The Children of Craig y Nos The Sleeping Giant Foundation People & Places The Welfare Hall Nature & Outdoors History "I've lived in Abercraf all my life. I was born and brought up Religion & Ethics in the same house. My mother was born in Abercraf. My Arts & Culture father was a Welsh-speaker and wouldn't speak to me in English. As you go down the valley, it's not so good - a bit Music more noisy. TV & Radio Local BBC Sites I went to Abercraf Primary School. It was a mining village at News the time and Abercraf colliery was still open. Most of the men Sport of the village worked in the colliery. These valleys are full of Weather coal. There's still open cast mining going on today. Travel Neighbouring Sites My father worked in Abercraf colliery. I used to play up in the North East Wales mountains and still walk there now - Cribarth and Llyn y Fan North West Wales Fawr and Llyn y Fan Fach. The colliery closed in the early South East Wales 1960s. -

Community Electoral Arrangements ) Order 2016

SCHEDULE TO THE COUNTY OF POWYS (COMMUNITY ELECTORAL ARRANGEMENTS ) ORDER 2016 FINAL PROPOSALS BRECKNOCKSHIRE No Community Wards – Pre Elector Councillo Total Summary of Finals Proposals Wards – Final Councillor Elec Cllrs 2006 s 2006 r Pre 2006 Councillor Proposals s Now tors Proposed s Pre 2006 Now 01 BRECON St. David Within 1225 3 Transfer a small part of the St David Within 3 1281 community of Glyn Tarell at Brecon Cattle Market at Ffrwdgrech to this community but affecting no electors St. John 2525 4 A new warding arrangement of St John East 3 836 St David Within 1225 3 four wards the St David Within St David Within 3 1281 St Mary 2102 5 ward as at pre 2006, the St Mary St John West 4 1758 ward bounded to the west by the St Marys 5 2002 river Honddu and to the south by the river Usk; the St John East ward bounded to the south-west by the B4520 and to the east by the river Honddu, and the St John West ward bounded to the north east by the B4520, to the east by the river Honddu and to the south by the river Usk. 12 Increasing the councillor 15 numbers from 12 to 15 02 BRONLLYS Pontywal 425 6 An adjustment in the ward Pontywal 6 408 boundary between the existing retained wards so that all the dwellings that lie to the south of the ridgeline that runs from the hill at Mintfield Farm to Long Cairn are included in the Pontywal ward instead of the Wye ward. -

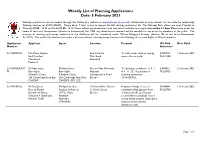

Weekly List of Planning Applications Date: 5 February 2021

Weekly List of Planning Applications Date: 5 February 2021 Planning applications can be viewed through the Authority’s website at www.beacons-npa.gov.uk, alternatively an appointment can be made by telephoning Planning Services on 01874 620431. Please allow 7 days’ notice to inspect the full planning application file. The National Park offices are open Monday to Thursday 09.00 - 16.45 and Friday 09.00 - 16.15. Please submit any observations you may have in relation to an application within 21 days. Please note under the terms of the Local Government (Access to Information) Act 1985, any observations received will be available for inspection by members of the public. The majority of planning applications submitted to the Authority will be considered under ‘Officer Delegated Powers’ (Section 101 of the Local Government Act1972). This enables the Authority to make a decision without referring an application to the Planning, Access and Rights of Way Committee. Application Applicant Agent Location Proposal OS Grid Date Valid Number Reference 21/19505/FUL Mrs Maria Hughes Red Cow Inn To add a small outdoor seating E:305736 1 February 2021 Red Cow Inn Main Road area in the car park. N:211388 Main Road Pontsticill Pontsticil 21/19509/DISCO Mr Rhys Jones Mr Rhys Jones Brecon War Memorial To discharge conditions 4, 6, 7, E:304921 2 February 2021 N Burroughs Burroughs Hospital 8, 9, 11, 12, 13 pursuant to N:228753 4 Radnor Court 4 Radnor Court Cerrigcochion Road planning permission 256 Cowbridge Road East 256 Cowbridge Road East Brecon 16/14336/FUL. -

Road Number Road Description A40 C B MONMOUTHSHIRE to 30

Road Number Road Description A40 C B MONMOUTHSHIRE TO 30 MPH GLANGRWYNEY A40 START OF 30 MPH GLANGRWYNEY TO END 30MPH GLANGRWYNEY A40 END OF 30 MPH GLANGRWYNEY TO LODGE ENTRANCE CWRT-Y-GOLLEN A40 LODGE ENTRANCE CWRT-Y-GOLLEN TO 30 MPH CRICKHOWELL A40 30 MPH CRICKHOWELL TO CRICKHOWELL A4077 JUNCTION A40 CRICKHOWELL A4077 JUNCTION TO END OF 30 MPH CRICKHOWELL A40 END OF 30 MPH CRICKHOWELL TO LLANFAIR U491 JUNCTION A40 LLANFAIR U491 JUNCTION TO NANTYFFIN INN A479 JUNCTION A40 NANTYFFIN INN A479 JCT TO HOEL-DRAW COTTAGE C115 JCT TO TRETOWER A40 HOEL-DRAW COTTAGE C115 JCT TOWARD TRETOWER TO C114 JCT TO TRETOWER A40 C114 JCT TO TRETOWER TO KESTREL INN U501 JCT A40 KESTREL INN U501 JCT TO TY-PWDR C112 JCT TO CWMDU A40 TY-PWDR C112 JCT TOWARD CWMDU TO LLWYFAN U500 JCT A40 LLWYFAN U500 JCT TO PANT-Y-BEILI B4560 JCT A40 PANT-Y-BEILI B4560 JCT TO START OF BWLCH 30 MPH A40 START OF BWLCH 30 MPH TO END OF 30MPH A40 FROM BWLCH BEND TO END OF 30 MPH A40 END OF 30 MPH BWLCH TO ENTRANCE TO LLANFELLTE FARM A40 LLANFELLTE FARM TO ENTRANCE TO BUCKLAND FARM A40 BUCKLAND FARM TO LLANSANTFFRAED U530 JUNCTION A40 LLANSANTFFRAED U530 JCT TO ENTRANCE TO NEWTON FARM A40 NEWTON FARM TO SCETHROG VILLAGE C106 JUNCTION A40 SCETHROG VILLAGE C106 JCT TO MILESTONE (4 MILES BRECON) A40 MILESTONE (4 MILES BRECON) TO NEAR OLD FORD INN C107 JCT A40 OLD FORD INN C107 JCT TO START OF DUAL CARRIAGEWAY A40 START OF DUAL CARRIAGEWAY TO CEFN BRYNICH B4558 JCT A40 CEFN BRYNICH B4558 JUNCTION TO END OF DUAL CARRIAGEWAY A40 CEFN BRYNICH B4558 JUNCTION TO BRYNICH ROUNDABOUT A40 BRYNICH ROUNDABOUT TO CEFN BRYNICH B4558 JUNCTION A40 BRYNICH ROUNDABOUT SECTION A40 BRYNICH ROUNABOUT TO DINAS STREAM BRIDGE A40 DINAS STREAM BRIDGE TO BRYNICH ROUNDABOUT ENTRANCE A40 OVERBRIDGE TO DINAS STREAM BRIDGE (REVERSED DIRECTION) A40 DINAS STREAM BRIDGE TO OVERBRIDGE A40 TARELL ROUNDABOUT TO BRIDLEWAY NO. -

Brycheiniog Vol 45:44036 Brycheiniog 2005 27/4/16 12:13 Page 1

81343_Brycheiniog_Vol_45:44036_Brycheiniog_2005 27/4/16 12:13 Page 1 BRYCHEINIOG Cyfnodolyn Cymdeithas Brycheiniog The Journal of the Brecknock Society CYFROL/VOLUME XLV 2014 Acting Editor JOHN NEWTON GIBBS Cyhoeddwyr/Publishers CYMDEITHAS BRYCHEINIOG A CHYFEILLION YR AMGUEDDFA THE BRECKNOCK SOCIETY AND MUSEUM FRIENDS 81343_Brycheiniog_Vol_45:44036_Brycheiniog_2005 27/4/16 12:13 Page 2 CYMDEITHAS BRYCHEINIOG a CHYFEILLION YR AMGUEDDFA THE BRECKNOCK SOCIETY and MUSEUM FRIENDS SWYDDOGION/OFFICERS Llywydd/President Mr Ken Jones Cadeirydd/Chairman Dr John Newton Gibbs Ysgrifenyddion Anrhydeddus/Honorary Secretaries Mrs Gwyneth Evans & Mrs Elaine Starling Aelodaeth/Membership Dr Elizabeth Siberry Trysorydd/Treasurer Mr Peter Jenkins Archwilydd/Auditor Mr Nick Morrell Golygydd/Editor Vacant Golygydd Cynorthwyol/Assistant Editor Mr Peter Jenkins Uwch Guradur Amgueddfa Brycheiniog/Senior Curator of the Brecknock Museum Mr Nigel Blackamore Pob Gohebiaeth: All Correspondence: Cymdeithas Brycheiniog, Brecknock Society, Amgueddfa Brycheiniog, Brecknock Museum, Rhodfa’r Capten, Captain’s Walk, Aberhonddu, Brecon, Powys LD3 7DS Powys LD3 7DS Ôl-rifynnau/Back numbers Mr Peter Jenkins Erthyglau a llyfrau am olygiaeth/Articles and books for review Dr John Newton Gibbs © Oni nodir fel arall, Cymdeithas Brycheiniog a Chyfeillion yr Amgueddfa piau hawlfraint yr erthyglau yn y rhifyn hwn © Except where otherwise noted, copyright of material published in this issue is vested in the Brecknock Society & Museum Friends 81343_Brycheiniog_Vol_45:44036_Brycheiniog_2005 -

Notice of Election Powys County Council - Election of Community Councillors

NOTICE OF ELECTION POWYS COUNTY COUNCIL - ELECTION OF COMMUNITY COUNCILLORS An election is to be held of Community Councillors for the whole of the County of Powys. Nomination papers must be delivered to the Returning Officer, County Hall, Llandrindod Wells, LD1 5LG on any week day after the date of this notice, but not later than 4.00pm, 4 APRIL 2017. Forms of nomination may be obtained at the address given below from the undersigned, who will, at the request of any elector for the said Electoral Division, prepare a nomination paper for signature. If the election is contested, the poll will take place on THURSDAY, 4 MAY 2017. Electors should take note that applications to vote by POST or requests to change or cancel an existing application must reach the Electoral Registration Officer at the address given below by 5.00pm on the 18 APRIL 2017. Applications to vote by PROXY must be made by 5.00pm on the 25 APRIL 2017. Applications to vote by PROXY on the grounds of physical incapacity or if your occupation, service or employment means you cannot go to a polling stations after the above deadlines must be made by 5.00 p.m. on POLLING DAY. Applications to be added to the Register of Electors in order to vote at this election must reach the Electoral Registration Officer by 13 April 2017. Applications can be made online at www.gov.uk/register-to-vote The address for obtaining and delivering nomination papers and for delivering applications for an absent vote is as follows: County Hall, Llandrindod Wells, LD1 5LG J R Patterson, Returning Officer -

Community No

FINAL PROPOSALS Community No. B30 - TAWE UCHAF Introduction 1. The community of Tawe Uchaf lies in the southeastern corner of Brecknockshire, in a landscape that is defined by the confluence of the upper river Tawe and the nant Llech. Settlement in this community is defined by the narrowing valleys and by the routes that follow them: the A4067 north-south route and the A4221 east-west route that converge at the community's western boundary. The main settlements of Coelbren, Caehopkin, Ynyswen and Pen-y-cae almost run into one another, and they give the impression of a built-up community. However, a significant part of this community, including Mynydd y Drum in the south and the steeply rising landscape to the north, comprises uninhabited moorland. 2. The northern half of the community, including the 2nd tier settlements of Ynyswen and Pen-y-cae, lies within the Brecon Beacons National Park. The southern half of the community lies within the remit of the Powys planning authority, and comprises the large villages of Caehopkin and Coelbren. 3. The community has a population of 1,516, an electorate of 1,265 (2005) and a council of 13 members. The community is warded: Caehopkin with 260 electors and three councillors; Coelbren with 513 and five; Penycae with 492 and 5. The precept required for 2005 is £13,500, representing a Council Tax Band D equivalent of £26.14. 4. The community of Tawe Uchaf was a product of the 1985 Review, when the former communities of Ystradgynlais Higher and Glyntawe were merged to form the new community. -

Southeast Wales & Brecon Beacons

© Lonely Planet Publications Pty Ltd SOUTHEAST WALES & BRECON BEACONS 3 PERFECT DAYS DAY 1 // FOLLOW THE RIVERS Spend the fi rst part of the day exploring the lower Wye Valley, starting at the impres- sive castle at Chepstow (p 74 ). Head upstream to the ghostly remains of Tintern Abbey (p 77 ) and then continue through the wooded gorge, crossing in and out of England, until you reach Monmouth (p 78 ). Have a quick look around but don’t stop just yet. Instead, follow the River Monnow to either Skenfrith (p 82 ) or Grosmont (p 83 ): they’re both wonderfully isolated hamlets, each with an ancient church, castle, good place to sleep and, of course, a village pub. DAY 2 // SPLENDID ISOLATION Continuing on roads less travelled, take the A465 to Llanfi hangel Crucorney (p 90 ) and journey through the heart of the Black Mountains on the lonely road traversing the Vale of Ewyas (p 90 ). Llanthony Priory’s photogenic ruins are worth a visit. Continue over Gospel Pass, soaking up the moody moorland vistas. Drop anchor in charming Hay-on-Wye (p 90 ), spending the afternoon rummaging through secondhand book- shops and antiques shops. Have dinner at one of the excellent pubs then check out whatever’s happening at the Globe. DAY 3 // FOOD FIRST Have a quick wander around Brecon (p 97 ) in the morning then continue towards Ab- ergavenny (p 83 ). Some of Wales’ best eateries lurk in country lanes along this route, so book for lunch and dinner. You can spend the afternoon walking off the calories, but if that sounds too physical, head to World Heritage–rated Blaenavon (p 104 ). -

25-26-27-28 August 2017

25-26-27-28 August 2017 www.zappi.clothing Race Founder: th John Richards 37 Edition One bank holiday, five stages, four jerseys, 100 riders aged 16-18, and 215 miles of the best racing roads in the UK. The 2017 SD Sealants Junior Tour of Wales sees the best junior cyclists from the UK and beyond converge on the roads of South Wales. From the opening time trial, held for the first time on Friday evening, to the final climactic climb of the Tumble Mountain on Bank Holi- day lunchtime, there will be no quarter given, and no let-up in the battle for the Yellow, After 9 rounds Pts Polka-Dot, Green and Blue Jerseys. 1 Oscar Mingay Wales 209 2 Harry Hardcastle Wheelbase Cabtech RT 198 The riders aren’t just racing against each 3 Daniel Coombe Wales 116 other – they are potentially competing for ca- = Harry Yates Hargroves-Ridley 116 reers as professional cyclists – and a place in 5 Ethan Vernon Team Corley Cycles 115 the history of a race that has already seen the likes of David Millar, Geraint Thomas, Mark 6 Thomas Pidcock PH-MAS/Paul Milnes 110 Cavendish, Alex Dowsett, Luke Rowe and 7 Jim Brown PH-MAS/Paul Milnes 104 Owain Doull graduate from the Junior Tour 8 Jake Stewart Swinnerton Cycles 98 podium to World Championships, World Re- 9 Jamie Ridehalgh Yorkshire 84 cords, Olympic Gold and the Tour de France. 10 Louis Rose-Davies Canyon UK 83 The Junior Tour can’t make riders great, but it 11 Mason Hollyman Bike Box Alan 78 has a knack of helping the great ones discover themselves. -

Local Government Boundary Commission for Wales

LOCAL GOVERNMENT BOUNDARY COMMISSION FOR WALES REVIEW OF ELECTORAL ARRANGEMENTS DRAFT PROPOSALS COUNTY OF POWYS LOCAL GOVERNMENT BOUNDARY COMMISSION FOR WALES REVIEW OF ELECTORAL ARRANGEMENTS FOR THE COUNTY OF POWYS DRAFT PROPOSALS 1. INTRODUCTION 2. SUMMARY OF PROPOSALS 3. SCOPE AND OBJECT OF THE REVIEW 4. REPRESENTATIONS RECEIVED PRIOR TO DRAFT PROPOSALS 5. ASSESSMENT 6. PROPOSALS 7. RESPONSES TO THIS REPORT APPENDIX 1 GLOSSARY OF TERMS APPENDIX 2 EXISTING COUNCIL MEMBERSHIP APPENDIX 3 PROPOSED COUNCIL MEMBERSHIP APPENDIX 4 MINISTER’S DIRECTIONS AND ADDITIONAL LETTER APPENDIX 5 SUMMARY OF INITIAL REPRESENTATIONS APPENDIX 6 MAP OF BRECON The Local Government Boundary Commission for Wales Caradog House 1-6 St Andrews Place CARDIFF CF10 3BE Tel Number: (029) 2039 5031 Fax Number: (029) 2039 5250 E-mail: [email protected] www.lgbc-wales.gov.uk FOREWORD Those who have received this report containing our Draft Proposals will already be aware of this Review of Electoral Arrangements for all local authority areas in Wales. An important principle for our work is to aim to achieve a better democratic balance within each council area so that each vote cast in an election is, so far as reasonably practicable, of the same weight as all others in the council area. The achievement of this aim, along with other measures, would be conducive to effective and convenient local government. At the beginning of this review process we have found some considerable differences between the numbers of voters to councillors not only between council areas in Wales, but also within council areas themselves. The Commission is constrained by a number of things in the way we undertake our work: • The basic “building blocks” for electoral divisions are the community areas into which Wales is divided. -

The Collieries of Abercrave

Pont-y-Yard Pont-y-Yard Pont-y-Yard Bridge, adjacent to the A 4067 just South of Abercrave, was one of the earliest stone bridges to span the River Tawe. It was built by Daniel Harpur, a local industrialist who came originally from Tamworth in Staffordshire. The bridge was intended as an aqueduct, to link the adjacent Lefel Fawr Colliery to the Swansea Canal at Hen-Neuadd dock, (now the site of Longs Coaches) This extension to the canal was never completed however, because of the gradient and the hardness of the local rock. Instead a horse-drawn tramway was built to take the coal to the canal and to the Abercrave Ironworks. The cottage by the bridge was occupied by the colliery manager. Just beyond the cottage you can see the barred entrance to the Lefel Fawr Mine which Daniel Harpur opened around 1801 . Notice the red-brown colour of the stream that flows from the entrance. This is due to iron which is often associated with coal seams. The colliery level was tunnelled for over a mile into the hillside by William Watkins a local engineer. He did not use explosives, and preferred to shatter the rock by harnessing the expansion produced when lime was slaked with water. The yard itself, which gave the bridge its name (bridge of the yard), was an area between the old Swansea Valley Canal feeder and the river Tawe. The main A 4067 road now runs across it. It was originally used to store and load coal from the Lefel Fawr mine. -

Brecon Beacons National Park Authority Retail Paper

Brecon Beacons National Park Authority Retail Paper 1 Brecon Beacons National Park Authority Retail Paper Contents 1. Introduction 2. Aims of this paper 3. Policy Context 4. The role, function and vitality of Identified Retail Centres 5. Survey Areas 6. Hierarchy of BBNPA Centres 7. Town centre Retail Health and Vitality 8. Accommodating Growth in retail 9. Accessibility 10. Visitors Survey 11. Place Plans and Retail Centres 12. Conclusions 13. References 2 Brecon Beacons National Park Authority Retail Paper 1. Introduction Purpose of the document Welsh Government’s Local Development Plan Manual Edition 2 (2015) states the following: ‘Section 69 of the 2004 Act requires a Local Planning Authority to undertake a review of an LDP and report to the Welsh Government at such times as prescribed. To ensure that there is a regular and comprehensive assessment of whether plans remain up-to-date or whether changes are needed an authority should commence a S69 full review of its LDP at intervals not longer than every 4 years from initial adoption and then from the date of the last adoption following a review under S69 (Regulation 41). A plan review should draw upon published AMRs, evidence gathered through updated survey evidence and pertinent contextual indicators, including relevant changes to national policy’. This document has been prepared to provide an evidence base and to examine retail in the Brecon Beacons National Park’s retail centres to inform policy for the replacement Local Development Plan. Evidence gathering information on past and existing circumstances to inform any changes to the retail strategy. This has been done through the analysis of time series data to help identify changes over recent years and any emerging patterns.